The political relationship between China and Japan has been strained for a long time. Time and again disputes arise over islands in the East China Sea and not least over a supposedly unsatisfactory apology by Japan for its crimes in China committed during World War II.

But for the most part, Japan managed to keep the political discord away from economic relations. Apart from brief boycotts of Japanese car brands, trade between the two countries continues to flourish today.

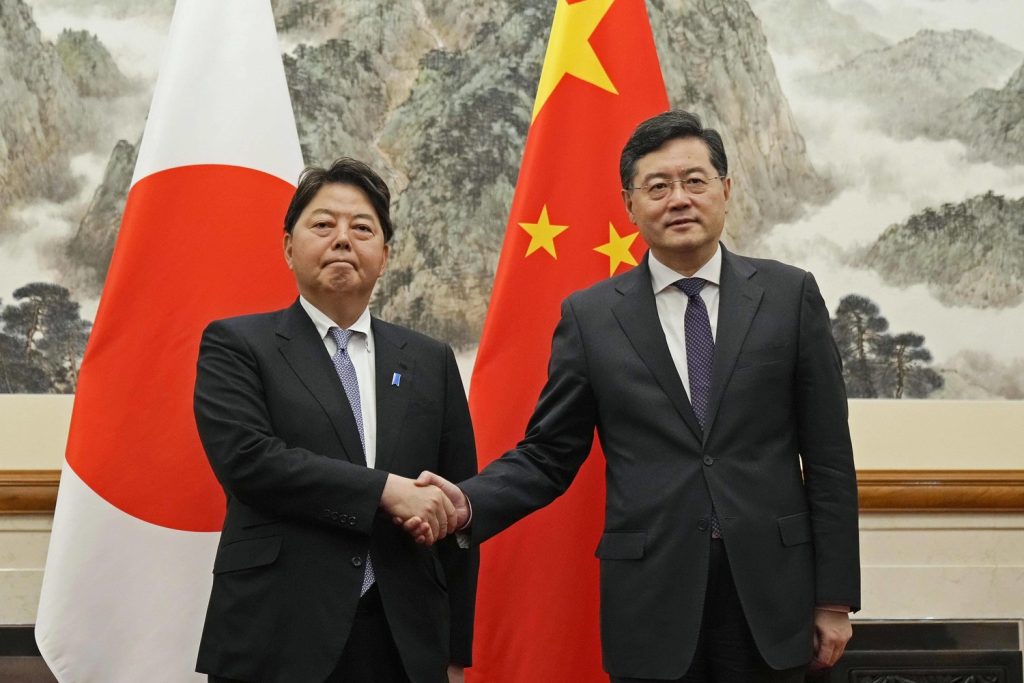

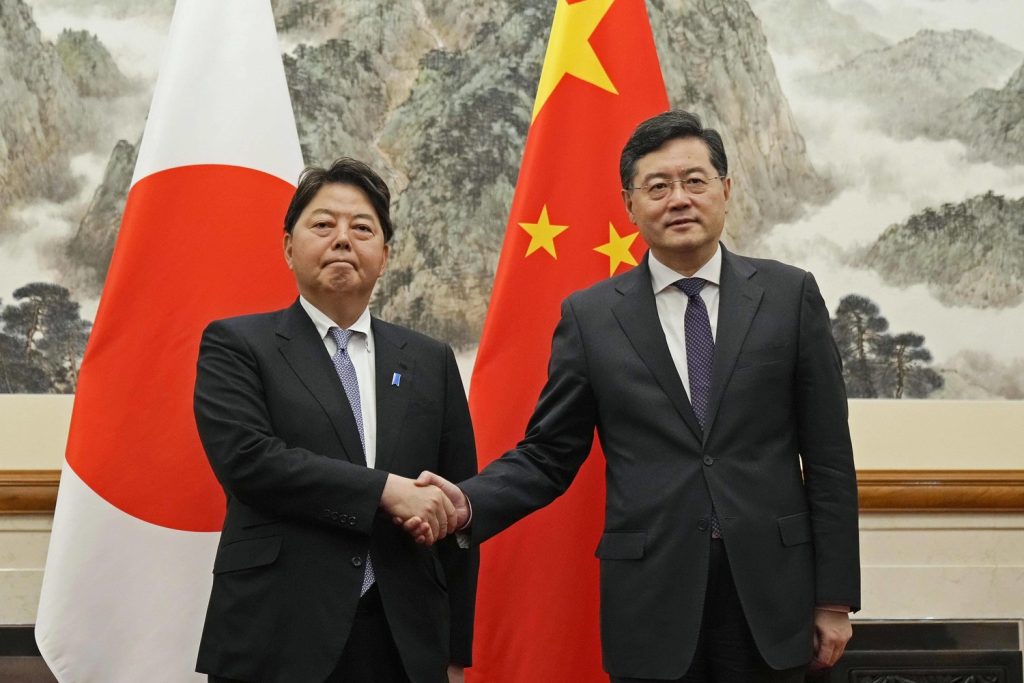

But this separation no longer seems to work in the wake of geopolitical tensions between China and the United States. Like the US government has asked the Netherlands to stop supplying China with special machinery for the production of advanced chips, Japan is now following Washington’s call. The meeting between Japanese Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi and his colleague Qin Gang in Beijing was correspondingly controversial, writes Finn Mayer-Kuckuk. At any rate, they were not smiling in their photo together.

Sometimes a view from the outside can help to better understand politics in one’s own country. This is also the case with the German Chancellor’s China strategy. Former US top diplomat John Cunningham considers Olaf Scholz’s hesitant approach to be out of date. The German economy is particularly vulnerable should the geopolitical tensions between the People’s Republic and the Western world increase further. Another wake-up call in these troubled times.

You are on a mission to Berlin to inform politicians on US concerns regarding human rights violations by China. How is chancellor Olaf Scholz’ stance on China perceived internationally?

Your chancellor has been playing a role in a world that’s more attuned to engagement with China than many others. Some parts of your political spectrum, as I understand it, have good reasons to engage with China. Our economies both have significant business exposure to China. There’s a manifest concern in our country that we need to find a way to rebalance that engagement, that it’s exposed us to too many kinds of threats in supply chains and other things that are not healthy.

What role does Scholz play here?

The German economy is particularly exposed among European countries. I know a debate has already started on this in your country, and I hope that that is a debate that will accelerate. Germany is important as a leader of world opinion and because of its important role in the European Union, where that debate also needs to be held.

Is Mr Scholz under particularly close scrutiny as his party comrade Mr. Schroeder has or had strong business links to the Russians?

I was still actively engaged in government when the debate about Nord Stream first began, and there were many Americans who felt that going down the path that Germany was going down, the pipeline would eventually become a real danger for Germany. Nobody thought it was going to manifest itself via the invasion of Ukraine. I would argue the same line of thought exists with China. It shows that the world that we thought we were creating after the fall of the Berlin Wall has not proved to be workable because you have authoritarian, powerful figures in China, in Moscow, who have two things that we don’t have in the West.

Which is?

They have a very clear vision of where they want to go. And they know what kind of world they want to see. Putin’s goal is the imperialist restoration of the Russian empire in some form or another. Xi Jinping’s is a restoration of Chinese grandeur and pushing a weak West off the international stage. They’ve been explicit about that in their writings and public statements.

Have the Germans understood this in all its implications?

There’s a surprising degree of consensus in the US Congress, and in our academia, about the dangers of overreliance on China. Sometimes that gets exaggerated and overstated depending on where you are on the political spectrum. But it is one of the few areas in that our political leaders and our parliamentarians have been able to find a center ground. It’s my sense that your national debate is moving in that direction, but it’s not as involved as it has been in the United States.

Germany, or the EU, do not necessarily have to follow the US. One question that concerns many people in Germany is about the behavior of the next U.S. administration. Joe Biden is tough on China but still in a controlled and calm way. But what are the scenarios for the future of US-China relations?

Our politics are a bit unpredictable, shall we say. But as I said earlier, one of the few areas where there seems to be a broad consensus, is over the nature of China. But there may be less consensus over what to do about it. We’ve made some pretty significant steps as a government over the past couple of years that have had broad bilateral support in Congress dealing with technology issues, dealing with chip issues in manufacturing, supply lines. We’re attracting foreign and American investment back to the United States. So we are rebalancing and are in the process of rebalancing our military efforts. The defense component of the budget that Biden sent to Congress was the largest defense budget in peacetime. A lot of that money is going to go to strengthening our posture in the Pacific.

As a diplomat, aren’t you concerned that the antagonism might be overstressed and relations might deteriorate to a very bad point?

That’s what the State Department and diplomats get paid for. One of the things that I think President Biden deserves a lot of credit for is that almost from the first day of his administration, he went about rebuilding our relationships with Europeans and countries in Asia that have been, shall we say, frayed under his predecessor. Long before anybody thought that there was going to be a crisis in Ukraine when those relationships would really matter. But what he did in rebuilding these coalitions, that’s diplomacy. And that’s the way you deal with these kinds of competitions. You need the military instrument to prevent bad outcomes.

Does armament not also lead to destabilization?

One of my good colleagues has been arguing for some time that the way to prevent war in Asia is to make sure that we’re prepared to fight war in Asia. And the Chinese realize that. Nobody wants to fight a war in Asia. One hopes the Chinese understand that they don’t want to fight a war in Asia. But in order to prevent that from happening, we need to have not just our own military strength, but we need to have a strong coalition of countries in Asia that are willing to be part of a political and diplomatic effort to manage China and prevent that from happening.

What is your assessment of the dangers for Taiwan?

The unknown here is there’s probably one person in China who gets to decide what happens in Taiwan. Maybe that one person is influenced by a small group of other people, but he doesn’t have a Congress or anything else to deal with. Presumably his military people are giving him advice about how difficult blockading Taiwan or even invading it would be. It is not an easy proposition. So with that said, you cannot exclude the possibility that one person would make what I think would be a historically disastrous decision for China and Asia. My guess is that we will continue to have friction and antagonism over Taiwan, but there’s no reason to think that we are actually going to be in a violent armed conflict over Taiwan for the foreseeable future. It just doesn’t make any sense.

James B. Cunningham is chairman of the Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation. The high-profile US diplomat was Consul General of the United States in Hong Kong 2005-2008, Ambassador to Israel 2008-2011 and Ambassador to Afghanistan 2012-2014. Before that he was Ambassador to the United Nations, Chief of Staff of the NATO secretary general and Director of the State Department’s Office of European Security and Political Affairs 1993-1995.

The Japanese government has followed the USA’s request and regulated the export of equipment for semiconductor production. In the future, companies that want such machines will need a permit from the Ministry of Commerce. The rules are to take effect in July. The ministry is now accepting applications for export licenses.

The ministry does not mention China specifically, but it is generally considered to be the target of the new export controls. This was also understood in Beijing. “To politicize, instrumentalize and weaponize trade and tech issues […] will eventually backfire,” a Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman said on Saturday in reaction to the move. It would be better to leave semiconductor supply chains to the market, she said. These are the usual phrases Beijing uses to respond to unfriendly trade measures.

The US began restricting the export of advanced chips and corresponding manufacturing machinery to China in October 2022. The People’s Republic is explicitly named in the administrative order from Washington. The reason given is China’s use of artificial intelligence for weapons and for monitoring both its own population and foreign citizens. The order was quickly given the name “US chip sanctions against China“.

But in order to effectively prevent China from developing its own manufacturing facilities, the US still had to bring partners on board. At its forefront here was the Netherlands, /china/en/feature/netherlands-join-chip-sanctions/which joined the sanctions after great lengths of US diplomacy last month. Here it was mainly the company ASML that attracted the interest of the USA and China. It manufactures machinery that can draw the smallest conductor paths on silicon baseplates.

However, the alliance against China’s semiconductor industry was still missing Japan, which is traditionally very strong in optoelectronics and semiconductor technology. The companies that are now affected include:

Legally, the Ministry of Economy and Trade METI has added 23 product groups related to semiconductor manufacturing to the list of goods covered by the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act. The ministry does not expect a severe impact on trade with China because the products in question, while very high-end, represent only a small part of the goods traded.

Japanese chip manufacturing equipment exports had already dropped significantly last year. This is considered a result of the US sanctions, as the Japanese business newspaper Nikkei reports. The corresponding exports fell by 16 percent in the final quarter of last year. US exports to China were down by 50 percent. The trend continued in the first quarter of 2023.

With China looking to rapidly expand its semiconductor industry, these downturns are probably not caused by the current poor chip business cycle, but by the sanctions. Without components from the USA and the Netherlands, the attempt to build new, advanced plants is futile. Accordingly, there have been no orders for components in Japan.

The new sanctions have made Yoshimasa Hayashi’s job more difficult. Japan’s Foreign Minister was in China over the weekend to meet the new Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang. The first visit in three years was supposed to improve the diplomatic climate.

The relationship between the neighboring countries was at rock bottom after Japan announced a significant arms build-up in its security strategy and a China strategy. At the meeting, Qin also criticized Japan’s plan to release radioactive water from the ruins of the Fukushima reactor into the sea.

Then there was last week’s arrest of an employee of the pharmaceutical company Astellas in Beijing. China accuses the Japanese citizen of espionage. At the meeting, Hayashi demanded the release of the person or at least transparency in the proceedings.

The meeting took three hours. While posing for a photo together, the two ministers could not bring themselves to smile. On the positive side, Hasashi was granted a meeting with Premier Li Qiang, which is a mark of honor from the Chinese side.

At the same time, China’s top foreign policy official Wang Yi warned in Beijing against a worsening of relations. Wang met with former Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda. The occasion was the 45th commemoration of the China-Japan Friendship Treaty, which ended the political ice age between the two countries at the time. Fukuda stressed that Japan was still interested in exchanges at the highest level.

Spain’s Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has called on Xi Jinping to hold talks with the Ukrainian government. “I transmitted our concern over the illegal invasion of Ukraine,” Sánchez said at his press conference in Beijing on Friday. He encouraged Xi to speak with President Volodymyr Zelenskiy so that he could learn first-hand about the Ukrainian peace plan, he said. This plan could then be the basis for a lasting peace in Ukraine and was perfectly in line with the United Nations Charter.

In its readout, Beijing mentioned Ukraine only in passing and with the familiar expressions: China’s position is clear, it is committed to peace talks and a political solution. China is willing to engage in comprehensive dialogue and cooperation with the EU “in the spirit of independence, mutual respect, mutual benefit, and seeking common ground while shelving differences”, Xi said. He expressed the hope that Spain could play a positive role in this.

Sánchez generally struck a more cooperative tone at his meetings than EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen did in her critical China speech at the end of last week. His meeting with the new Premier Li Qiang mainly focused on economic issues. Both countries have drawn up an implementation plan for cooperation until 2026, which includes imports of Spanish agricultural products, cooperation in education, crop protection and sports, the Spanish agency EFE reports. Li stressed that Beijing is keen to increase trade with Spain for solar panels as well as olive oil and wine from Spain. ck

The UK is about to become the first European country to join the trans-Pacific free trade alliance CPTPP. The acronym stands for Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. According to London, it has already reached an agreement with the eleven member countries.

“Joining the CPTPP trade bloc puts the UK at the center of a dynamic and growing group of Pacific economies,” Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said on Friday night. Admission to the Pacific Rim trade pact is expected to be finalized by the end of this year, according to the PM, and would be the UK’s first post-Brexit membership. China and Taiwan are also keen to be part of the CPTPP and have submitted membership applications.

“British businesses will now enjoy unparalleled access to markets from Europe to the south Pacific,” Sunak said. Accession will add 1.8 billion pounds (about 2 billion euros) to the country’s economic output in the long term, according to a government statement. Members of the free trade area, which was founded in 2018, include Japan, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, Singapore and Vietnam. Together, the CPTPP members account for 13 percent of global economic output so far.

With China involved in the agreement, this figure would increase to almost 28 percent. At present, the People’s Republic is maintaining contacts, communication and consultation with all parties, a spokeswoman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry said. She left it open whether any progress has been made. ari

The Minister-President of the German state of Lower Saxony, Stephan Weil, has defended Volkswagen against criticism of its plant in the Chinese Uyghur province of Xinjiang. “Volkswagen is by no means driving with its eyes closed,” said the SPD politician. “Everyone is aware that VW is under very close scrutiny.” Weil went on to say that the joint venture in the city of Urumqi was of mere secondary economic importance for VW.

As with many other investments in countries where human rights are threatened, he said, the question is: “Would it be better for the local people in the company if it withdrew?” Because the federal state has a stake in the company, Weil sits on VW’s supervisory board. “I remember Nelson Mandela who, after the end of apartheid in South Africa, thanked the Western companies that stayed despite the sanctions. That gave people courage,” he added. “The discussion is not black and white, and VW is anything but blue-eyed.”

VW China board member Ralf Brantstaetter emphasized at the end of February that VW and its Chinese partner SAIC agree “that we do not tolerate human rights violations in our plants“. The Chinese leadership is accused of oppressing the Uyghur Muslim minority in the northwest of the country. Beijing rejects this.

Volkswagen opened the plant in Urumqi with a capacity of 50,000 vehicles in 2012. During the Covid pandemic and due to delivery bottlenecks, the workforce shrank by 65 percent to just under 240 employees. rtr

Eric Xu, rotating chairman of Huawei, does not believe that US sanctions against China’s chip industry will succeed. “China’s semiconductor industry will not sit idly by, but take efforts around … self-strengthening and self-reliance. I believe China’s semiconductor industry will get reborn under such sanctions and realize a very strong and self-reliant industry,” Xu said at a press conference on his company’s annual results on Friday. Huawei will support all efforts to become independent, for example with new, in-house software, he said.

As Huawei reported on Friday, the company was able to post slight sales growth in 2022 despite US sanctions. Revenue last year rose 0.9 percent year-on-year to 642 billion yuan, the equivalent of 85 billion euros – a turnaround after a nearly 30 percent decline the year before. “2022 is the year that we pulled ourselves out of crisis mode. We’re back to business as normal,” said Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou, the daughter and crown princess of Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei.

However, Huawei’s net profit fell to 36 billion yuan in 2022, a drop of almost 70 percent from the previous year’s 114 billion yuan. At that time, Huawei sold its low-cost smartphone brand Honor. Huawei also attributed the profit decline to growing labor costs, rising commodity prices and more R&D spending. Meng said Huawei spent 162 billion yuan on research and development last year – equivalent to a quarter of sales. “In times of pressure, we press on – with confidence,” Meng said. fpe

China has launched an investigation against the US semiconductor manufacturer Micron. The Cyberspace Administration of China announced that Micron would pose a security risk. Micron is the largest US memory chip manufacturer. Observers see the investigation as a tit-for-tat response to the US sanctions against China’s semiconductor industry, which Japan recently joined. Micron assured its full cooperation with the Chinese authorities.

Micron itself warned in its latest annual report of difficulties in the Chinese market due to the sanctions. The company also fears being cut off from supplies of raw materials such as rare earths from China. The Chinese government is currently trying to push its own memory manufacturers like Yangtze Memory Technologies. fin

A Chinese-German volume of poems that fell into her hands as a schoolgirl sparked Susanne Hornfeck’s enthusiasm for China. She was fascinated by the strange characters. But little did she know at the time that this fascination would stay with her for decades to come. Later, Hornfeck studied Sinology, German Studies and German as a Foreign Language in Tuebingen, London and Munich. She then went to Taipei for five years as a DAAD lecturer, where she taught German.

When she returned to Germany, she began translating freelance from English and Chinese – and has been doing so for almost 30 years now. “Back then I found exactly what I like to do,” says Hornfeck, who sees every book as a new challenge. It is always a matter of finding the right style and tone for the protagonists. “I like to play with language, tweak sentences and try not to get stuck in the structures of the source language.”

But as much as Hornfeck likes to translate – every now and then she wants to “make the puppets dance” herself, as she says. Then she writes novels for young people that “turn history into stories”. She brought the material for her first novel, “Ina aus China” (Ina from China), with her from Taiwan. In it, she tells the story of a former colleague who was sent to Nazi-era Germany at the age of seven by her father, a banker from Shanghai. “I want to make history interesting for young people,” Hornfeck says. When her second novel, Torte mit Staebchen (Cake with Chopsticks), won the Youth Jury Prize at the Literaturhaus Wien, one of the young jurors commented: “There’s a lot of history in the book, but it’s not boring at all.” For Hornfeck, the highest praise.

Shanghai is a recurring setting in her books. On the one hand, she feels a close connection to the city. On the other hand, Shanghai has a connection to Germany that few people know about: “During the Nazi era, about 20,000 German and Austrian Jews were able to emigrate there and thus survived the Holocaust,” the author reports. Apart from her youth historical novels, Hornfeck also wrote several non-fiction books – among others about Chinese healing cuisine and Chinese home remedies.

The title of Hornfeck’s current book is “Taiwankatze – eine Grenzueberschreitung” (Taiwan Cat – crossing borders). In it, she tells of her everyday life as a young university lecturer in Taiwan. “It’s about living and managing in a foreign culture and returning home to the supposedly familiar, which you suddenly see with different eyes,” Hornfeck says.

A cat that she took over from friends helped her during this time. It was only supposed to take care of the ubiquitous rats on campus, but instead, it gave life advice with intuitive feline wisdom and gently nudged Hornfeck in the right direction again and again. Later, “Shaobai” – as the Taiwanese cat is actually called – had to learn how to adapt to a foreign culture herself. Hornfeck took it with her to Germany. Svenja Napp

Kevin Schwenk took over the position of Liaison Manager China at Afag Group this month. The Swiss-based company supplies components for assembly automation. The trained industrial mechanic and team leader in internal sales will perform his new duties from Locherhof in Germany.

Hu Xeyi, former chairman of Beijing carmaker BAIC, is the subject of corruption investigations by the CCP. BAIC is a production partner of Mercedes-Benz.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

At work, we pitch projects using fancy powerpoints, juggle millions, create trend-setting analyses. And at home? We are reduced to poop shoveling officials by our pets.

China’s linguistic acrobats have long since faced this reality and packaged it in the charming term of 铲屎官 chǎnshǐguān, lately a tongue-in-cheek synonym for “pet owner”. The ironic self-title is composed of the characters 铲 chǎn “shovel” or “shovel, shovel, spade”, 屎 shǐ “excrement, dung, shit” and 官 guān “civil servant”. Poop shoveling public servants are thus primarily responsible for the state-bearing task of shoveling away, picking up and bagging up pet poop.

Let’s not fool ourselves: We may think we are the masters of our beloved four-legged friends in fits of arrogance and megalomania. But when our furry friends leave a pile we need to clean up, we are instantly brought back down to the ground. Charmed by cute woof-woofs and meows, we willingly allow ourselves to be instrumentalized for all kinds of menial tasks. By the way, new Chinese also has a fitting term for this: the “tool person”, pronounced 工具人 gōngjùrén. For our pets, we are mainly used as can openers and fur-scratching machines at the end of the day.

Keywords such as “mutt excrement cadre” or “kitty poop manager” also lead us straight to a range of topics that are usually given a wide berth in Chinese lessons: shitology. Unjustly, in my opinion! For one thing, everything that goes in must come out again at some point. But more importantly, dealing with seemingly less-than-pleasant foreign words can be an entertaining and enlightening experience, at least in Mandarin. So let us delve deep into intercultural poop insights!

The dictionary defines “poop” as solid human excretion. If one wants to express oneself more specifically in China (e.g. at the doctor’s), number two should be called 大便 dàbiàn (literally “big convenience” – from 大 dà “big” and 方便 fāngbiàn “effortless, convenient, practical”). The number one is logically called “small convenience” (小便 xiǎobiàn). If you want to go to the bathroom tactfully, it is best to say 我去方便一下 wǒ qù fāngbiàn yíxià, meaning “I’m going to relieve myself” (literally, “I’m going to make myself comfortable”). But in the end, no one really wants to know.

As we have already seen, number two can be named straight away with the Hanzi 屎shǐ. That’s right. In Chinese, poop also has its own character, a very succinct one at that. 屎 is made up of the phonetic component 尸 shī, which actually means corpse, and 米 mǐ for “(husked) rice”. Rice that comes out of a body, so to speak – that sums things up quite well in a few brushstrokes.

Meanwhile, the ordinary version of defecate is 拉屎 lāshǐ, from 拉 lā “(to) pull out”. Perhaps better memorized simply as the Chinese version of “to take a dump”. Incidentally, the word 拉屎 lāshǐ also appears in some pleasant idioms. For example, in 鸡不生蛋狗不拉屎 jī bù shēngdàn gǒu bù lāshǐ, literally “where chickens don’t lay eggs and dogs don’t shit”, or “the arse end of the world”. Or also in the expression 占着茅坑不拉屎 zhànzhe máokēng bù lāshǐ, “to occupy the toilet and not to shit”, which, depending on the context, means either “spoilsport” or the bad habit of idly and incompetently blocking a post without letting more suitable candidates take over.

The character 屎 is worth remembering anyway, as it conveniently combines many other words that our body naturally secretes and excretes every day. For example, “nasal manure” (鼻屎 bíshǐ – Chinese for boogers), “ear shit” (耳屎ěrshǐ – ear wax) and “eye shit” (眼屎 yǎnshǐ – sleepy-seeds, sleepies).

Thanks to the already-mentioned poop vocabulary, you will certainly quickly figure out the riddle of what the character 尿 is all about. This time, something liquid is obviously going into the bowl, indicated by the component 水 shuǐ “water”. Correct: 尿, pronounced niào, is the hanzi for “urine” or even “to urinate.” In the vernacular, it also appears in the variants 尿尿 niàoniào “to pee” or 撒尿 sāniào “to pee” (literally actually “to scatter urine”).

If you really want to upset your fellow Chinese while standing in line at the toilet, just round your lips cheerfully and start a constant, monotonous continuous whistling tone. For many Chinese, this acoustic trigger pushes directly on the bladder, so that there is almost no holding back. This is because Chinese parents whistle to encourage their little ones to tinkle, whenever they are taking their sweet time. This seems to have etched itself deeply into people’s acoustic memory, like a Pavlovian pee whistle, even into adulthood.

Fortunately, the offspring can manage without fixed pee times if they are strapped into a diaper. Colloquially, this has the wonderful name 尿不湿 niàobùshī, which translates roughly as “does not get wet when peeing” (尿 niào = pee, 不 bù = not, 湿 shī = wet, moist). Another ingenious invention in this context are Chinese slit pants, which sometimes make foreigners smirk during their first visits to Chinese rural areas. In the case of these baby or toddler pants, the material that could get wet in the worst case was simply left out, namely the crotch. Problem solved. In Chinese, the underpants are simply called 开裆裤 kāidāngkù – “pants with open crotch”.

Even for us adults, the bladder sometimes squeezes at the wrong time, for example at the movies or during shows. Unfortunately, this usually happens just when things are getting exciting. Conversely, there are also sometimes dramaturgical lulls, i.e. dull parts that are only good for a bathroom break. China’s youth has therefore christened such boring scenes and sequences simply 尿点 niàodiǎn, i.e. “pee points” or “pee times”. Other “points” in the linguistic timeline would be the “tear point” (泪点 lèidiǎn – meaning a particularly touching scene) or the “laugh point” (笑点 xiàodiǎn – a funny scene or punch line).

But let’s get back to the restroom. In Mandarin, it is called 厕所 cèsuǒ (“toilet”). And in China, people also go to the bathroom (上厕所 shàng cèsuǒ – from 上 “to go, to go up”). Somewhat more refined variations of the word would be the “hand-washing room” (洗手间 xǐshǒujiān) or the “hygiene room” (卫生间 wèishēngjiān). However, the crucial question facing all bathroom-goers in the Middle Kingdom is: squat or sit? Because in public places like airports or shopping malls, you usually have the choice between squat toilets (蹲坑厕所 dūnkēng cèsuǒ or 坑 kēng for short, literally “pit”) or the so-called “horse bucket” (马桶 mǎtǒng), which is the Chinese name for our Western toilet bowl. While many Chinese have long since discovered the advantages of the seated toilet in their own homes, and even luxury versions based on the Japanese model (with heated seat and massage jet) are selling like hotcakes in the new middle class, many still prefer the classic squat toilet in public toilets, mostly for hygienic reasons.

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.

The political relationship between China and Japan has been strained for a long time. Time and again disputes arise over islands in the East China Sea and not least over a supposedly unsatisfactory apology by Japan for its crimes in China committed during World War II.

But for the most part, Japan managed to keep the political discord away from economic relations. Apart from brief boycotts of Japanese car brands, trade between the two countries continues to flourish today.

But this separation no longer seems to work in the wake of geopolitical tensions between China and the United States. Like the US government has asked the Netherlands to stop supplying China with special machinery for the production of advanced chips, Japan is now following Washington’s call. The meeting between Japanese Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi and his colleague Qin Gang in Beijing was correspondingly controversial, writes Finn Mayer-Kuckuk. At any rate, they were not smiling in their photo together.

Sometimes a view from the outside can help to better understand politics in one’s own country. This is also the case with the German Chancellor’s China strategy. Former US top diplomat John Cunningham considers Olaf Scholz’s hesitant approach to be out of date. The German economy is particularly vulnerable should the geopolitical tensions between the People’s Republic and the Western world increase further. Another wake-up call in these troubled times.

You are on a mission to Berlin to inform politicians on US concerns regarding human rights violations by China. How is chancellor Olaf Scholz’ stance on China perceived internationally?

Your chancellor has been playing a role in a world that’s more attuned to engagement with China than many others. Some parts of your political spectrum, as I understand it, have good reasons to engage with China. Our economies both have significant business exposure to China. There’s a manifest concern in our country that we need to find a way to rebalance that engagement, that it’s exposed us to too many kinds of threats in supply chains and other things that are not healthy.

What role does Scholz play here?

The German economy is particularly exposed among European countries. I know a debate has already started on this in your country, and I hope that that is a debate that will accelerate. Germany is important as a leader of world opinion and because of its important role in the European Union, where that debate also needs to be held.

Is Mr Scholz under particularly close scrutiny as his party comrade Mr. Schroeder has or had strong business links to the Russians?

I was still actively engaged in government when the debate about Nord Stream first began, and there were many Americans who felt that going down the path that Germany was going down, the pipeline would eventually become a real danger for Germany. Nobody thought it was going to manifest itself via the invasion of Ukraine. I would argue the same line of thought exists with China. It shows that the world that we thought we were creating after the fall of the Berlin Wall has not proved to be workable because you have authoritarian, powerful figures in China, in Moscow, who have two things that we don’t have in the West.

Which is?

They have a very clear vision of where they want to go. And they know what kind of world they want to see. Putin’s goal is the imperialist restoration of the Russian empire in some form or another. Xi Jinping’s is a restoration of Chinese grandeur and pushing a weak West off the international stage. They’ve been explicit about that in their writings and public statements.

Have the Germans understood this in all its implications?

There’s a surprising degree of consensus in the US Congress, and in our academia, about the dangers of overreliance on China. Sometimes that gets exaggerated and overstated depending on where you are on the political spectrum. But it is one of the few areas in that our political leaders and our parliamentarians have been able to find a center ground. It’s my sense that your national debate is moving in that direction, but it’s not as involved as it has been in the United States.

Germany, or the EU, do not necessarily have to follow the US. One question that concerns many people in Germany is about the behavior of the next U.S. administration. Joe Biden is tough on China but still in a controlled and calm way. But what are the scenarios for the future of US-China relations?

Our politics are a bit unpredictable, shall we say. But as I said earlier, one of the few areas where there seems to be a broad consensus, is over the nature of China. But there may be less consensus over what to do about it. We’ve made some pretty significant steps as a government over the past couple of years that have had broad bilateral support in Congress dealing with technology issues, dealing with chip issues in manufacturing, supply lines. We’re attracting foreign and American investment back to the United States. So we are rebalancing and are in the process of rebalancing our military efforts. The defense component of the budget that Biden sent to Congress was the largest defense budget in peacetime. A lot of that money is going to go to strengthening our posture in the Pacific.

As a diplomat, aren’t you concerned that the antagonism might be overstressed and relations might deteriorate to a very bad point?

That’s what the State Department and diplomats get paid for. One of the things that I think President Biden deserves a lot of credit for is that almost from the first day of his administration, he went about rebuilding our relationships with Europeans and countries in Asia that have been, shall we say, frayed under his predecessor. Long before anybody thought that there was going to be a crisis in Ukraine when those relationships would really matter. But what he did in rebuilding these coalitions, that’s diplomacy. And that’s the way you deal with these kinds of competitions. You need the military instrument to prevent bad outcomes.

Does armament not also lead to destabilization?

One of my good colleagues has been arguing for some time that the way to prevent war in Asia is to make sure that we’re prepared to fight war in Asia. And the Chinese realize that. Nobody wants to fight a war in Asia. One hopes the Chinese understand that they don’t want to fight a war in Asia. But in order to prevent that from happening, we need to have not just our own military strength, but we need to have a strong coalition of countries in Asia that are willing to be part of a political and diplomatic effort to manage China and prevent that from happening.

What is your assessment of the dangers for Taiwan?

The unknown here is there’s probably one person in China who gets to decide what happens in Taiwan. Maybe that one person is influenced by a small group of other people, but he doesn’t have a Congress or anything else to deal with. Presumably his military people are giving him advice about how difficult blockading Taiwan or even invading it would be. It is not an easy proposition. So with that said, you cannot exclude the possibility that one person would make what I think would be a historically disastrous decision for China and Asia. My guess is that we will continue to have friction and antagonism over Taiwan, but there’s no reason to think that we are actually going to be in a violent armed conflict over Taiwan for the foreseeable future. It just doesn’t make any sense.

James B. Cunningham is chairman of the Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation. The high-profile US diplomat was Consul General of the United States in Hong Kong 2005-2008, Ambassador to Israel 2008-2011 and Ambassador to Afghanistan 2012-2014. Before that he was Ambassador to the United Nations, Chief of Staff of the NATO secretary general and Director of the State Department’s Office of European Security and Political Affairs 1993-1995.

The Japanese government has followed the USA’s request and regulated the export of equipment for semiconductor production. In the future, companies that want such machines will need a permit from the Ministry of Commerce. The rules are to take effect in July. The ministry is now accepting applications for export licenses.

The ministry does not mention China specifically, but it is generally considered to be the target of the new export controls. This was also understood in Beijing. “To politicize, instrumentalize and weaponize trade and tech issues […] will eventually backfire,” a Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman said on Saturday in reaction to the move. It would be better to leave semiconductor supply chains to the market, she said. These are the usual phrases Beijing uses to respond to unfriendly trade measures.

The US began restricting the export of advanced chips and corresponding manufacturing machinery to China in October 2022. The People’s Republic is explicitly named in the administrative order from Washington. The reason given is China’s use of artificial intelligence for weapons and for monitoring both its own population and foreign citizens. The order was quickly given the name “US chip sanctions against China“.

But in order to effectively prevent China from developing its own manufacturing facilities, the US still had to bring partners on board. At its forefront here was the Netherlands, /china/en/feature/netherlands-join-chip-sanctions/which joined the sanctions after great lengths of US diplomacy last month. Here it was mainly the company ASML that attracted the interest of the USA and China. It manufactures machinery that can draw the smallest conductor paths on silicon baseplates.

However, the alliance against China’s semiconductor industry was still missing Japan, which is traditionally very strong in optoelectronics and semiconductor technology. The companies that are now affected include:

Legally, the Ministry of Economy and Trade METI has added 23 product groups related to semiconductor manufacturing to the list of goods covered by the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act. The ministry does not expect a severe impact on trade with China because the products in question, while very high-end, represent only a small part of the goods traded.

Japanese chip manufacturing equipment exports had already dropped significantly last year. This is considered a result of the US sanctions, as the Japanese business newspaper Nikkei reports. The corresponding exports fell by 16 percent in the final quarter of last year. US exports to China were down by 50 percent. The trend continued in the first quarter of 2023.

With China looking to rapidly expand its semiconductor industry, these downturns are probably not caused by the current poor chip business cycle, but by the sanctions. Without components from the USA and the Netherlands, the attempt to build new, advanced plants is futile. Accordingly, there have been no orders for components in Japan.

The new sanctions have made Yoshimasa Hayashi’s job more difficult. Japan’s Foreign Minister was in China over the weekend to meet the new Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang. The first visit in three years was supposed to improve the diplomatic climate.

The relationship between the neighboring countries was at rock bottom after Japan announced a significant arms build-up in its security strategy and a China strategy. At the meeting, Qin also criticized Japan’s plan to release radioactive water from the ruins of the Fukushima reactor into the sea.

Then there was last week’s arrest of an employee of the pharmaceutical company Astellas in Beijing. China accuses the Japanese citizen of espionage. At the meeting, Hayashi demanded the release of the person or at least transparency in the proceedings.

The meeting took three hours. While posing for a photo together, the two ministers could not bring themselves to smile. On the positive side, Hasashi was granted a meeting with Premier Li Qiang, which is a mark of honor from the Chinese side.

At the same time, China’s top foreign policy official Wang Yi warned in Beijing against a worsening of relations. Wang met with former Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda. The occasion was the 45th commemoration of the China-Japan Friendship Treaty, which ended the political ice age between the two countries at the time. Fukuda stressed that Japan was still interested in exchanges at the highest level.

Spain’s Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has called on Xi Jinping to hold talks with the Ukrainian government. “I transmitted our concern over the illegal invasion of Ukraine,” Sánchez said at his press conference in Beijing on Friday. He encouraged Xi to speak with President Volodymyr Zelenskiy so that he could learn first-hand about the Ukrainian peace plan, he said. This plan could then be the basis for a lasting peace in Ukraine and was perfectly in line with the United Nations Charter.

In its readout, Beijing mentioned Ukraine only in passing and with the familiar expressions: China’s position is clear, it is committed to peace talks and a political solution. China is willing to engage in comprehensive dialogue and cooperation with the EU “in the spirit of independence, mutual respect, mutual benefit, and seeking common ground while shelving differences”, Xi said. He expressed the hope that Spain could play a positive role in this.

Sánchez generally struck a more cooperative tone at his meetings than EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen did in her critical China speech at the end of last week. His meeting with the new Premier Li Qiang mainly focused on economic issues. Both countries have drawn up an implementation plan for cooperation until 2026, which includes imports of Spanish agricultural products, cooperation in education, crop protection and sports, the Spanish agency EFE reports. Li stressed that Beijing is keen to increase trade with Spain for solar panels as well as olive oil and wine from Spain. ck

The UK is about to become the first European country to join the trans-Pacific free trade alliance CPTPP. The acronym stands for Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. According to London, it has already reached an agreement with the eleven member countries.

“Joining the CPTPP trade bloc puts the UK at the center of a dynamic and growing group of Pacific economies,” Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said on Friday night. Admission to the Pacific Rim trade pact is expected to be finalized by the end of this year, according to the PM, and would be the UK’s first post-Brexit membership. China and Taiwan are also keen to be part of the CPTPP and have submitted membership applications.

“British businesses will now enjoy unparalleled access to markets from Europe to the south Pacific,” Sunak said. Accession will add 1.8 billion pounds (about 2 billion euros) to the country’s economic output in the long term, according to a government statement. Members of the free trade area, which was founded in 2018, include Japan, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, Singapore and Vietnam. Together, the CPTPP members account for 13 percent of global economic output so far.

With China involved in the agreement, this figure would increase to almost 28 percent. At present, the People’s Republic is maintaining contacts, communication and consultation with all parties, a spokeswoman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry said. She left it open whether any progress has been made. ari

The Minister-President of the German state of Lower Saxony, Stephan Weil, has defended Volkswagen against criticism of its plant in the Chinese Uyghur province of Xinjiang. “Volkswagen is by no means driving with its eyes closed,” said the SPD politician. “Everyone is aware that VW is under very close scrutiny.” Weil went on to say that the joint venture in the city of Urumqi was of mere secondary economic importance for VW.

As with many other investments in countries where human rights are threatened, he said, the question is: “Would it be better for the local people in the company if it withdrew?” Because the federal state has a stake in the company, Weil sits on VW’s supervisory board. “I remember Nelson Mandela who, after the end of apartheid in South Africa, thanked the Western companies that stayed despite the sanctions. That gave people courage,” he added. “The discussion is not black and white, and VW is anything but blue-eyed.”

VW China board member Ralf Brantstaetter emphasized at the end of February that VW and its Chinese partner SAIC agree “that we do not tolerate human rights violations in our plants“. The Chinese leadership is accused of oppressing the Uyghur Muslim minority in the northwest of the country. Beijing rejects this.

Volkswagen opened the plant in Urumqi with a capacity of 50,000 vehicles in 2012. During the Covid pandemic and due to delivery bottlenecks, the workforce shrank by 65 percent to just under 240 employees. rtr

Eric Xu, rotating chairman of Huawei, does not believe that US sanctions against China’s chip industry will succeed. “China’s semiconductor industry will not sit idly by, but take efforts around … self-strengthening and self-reliance. I believe China’s semiconductor industry will get reborn under such sanctions and realize a very strong and self-reliant industry,” Xu said at a press conference on his company’s annual results on Friday. Huawei will support all efforts to become independent, for example with new, in-house software, he said.

As Huawei reported on Friday, the company was able to post slight sales growth in 2022 despite US sanctions. Revenue last year rose 0.9 percent year-on-year to 642 billion yuan, the equivalent of 85 billion euros – a turnaround after a nearly 30 percent decline the year before. “2022 is the year that we pulled ourselves out of crisis mode. We’re back to business as normal,” said Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou, the daughter and crown princess of Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei.

However, Huawei’s net profit fell to 36 billion yuan in 2022, a drop of almost 70 percent from the previous year’s 114 billion yuan. At that time, Huawei sold its low-cost smartphone brand Honor. Huawei also attributed the profit decline to growing labor costs, rising commodity prices and more R&D spending. Meng said Huawei spent 162 billion yuan on research and development last year – equivalent to a quarter of sales. “In times of pressure, we press on – with confidence,” Meng said. fpe

China has launched an investigation against the US semiconductor manufacturer Micron. The Cyberspace Administration of China announced that Micron would pose a security risk. Micron is the largest US memory chip manufacturer. Observers see the investigation as a tit-for-tat response to the US sanctions against China’s semiconductor industry, which Japan recently joined. Micron assured its full cooperation with the Chinese authorities.

Micron itself warned in its latest annual report of difficulties in the Chinese market due to the sanctions. The company also fears being cut off from supplies of raw materials such as rare earths from China. The Chinese government is currently trying to push its own memory manufacturers like Yangtze Memory Technologies. fin

A Chinese-German volume of poems that fell into her hands as a schoolgirl sparked Susanne Hornfeck’s enthusiasm for China. She was fascinated by the strange characters. But little did she know at the time that this fascination would stay with her for decades to come. Later, Hornfeck studied Sinology, German Studies and German as a Foreign Language in Tuebingen, London and Munich. She then went to Taipei for five years as a DAAD lecturer, where she taught German.

When she returned to Germany, she began translating freelance from English and Chinese – and has been doing so for almost 30 years now. “Back then I found exactly what I like to do,” says Hornfeck, who sees every book as a new challenge. It is always a matter of finding the right style and tone for the protagonists. “I like to play with language, tweak sentences and try not to get stuck in the structures of the source language.”

But as much as Hornfeck likes to translate – every now and then she wants to “make the puppets dance” herself, as she says. Then she writes novels for young people that “turn history into stories”. She brought the material for her first novel, “Ina aus China” (Ina from China), with her from Taiwan. In it, she tells the story of a former colleague who was sent to Nazi-era Germany at the age of seven by her father, a banker from Shanghai. “I want to make history interesting for young people,” Hornfeck says. When her second novel, Torte mit Staebchen (Cake with Chopsticks), won the Youth Jury Prize at the Literaturhaus Wien, one of the young jurors commented: “There’s a lot of history in the book, but it’s not boring at all.” For Hornfeck, the highest praise.

Shanghai is a recurring setting in her books. On the one hand, she feels a close connection to the city. On the other hand, Shanghai has a connection to Germany that few people know about: “During the Nazi era, about 20,000 German and Austrian Jews were able to emigrate there and thus survived the Holocaust,” the author reports. Apart from her youth historical novels, Hornfeck also wrote several non-fiction books – among others about Chinese healing cuisine and Chinese home remedies.

The title of Hornfeck’s current book is “Taiwankatze – eine Grenzueberschreitung” (Taiwan Cat – crossing borders). In it, she tells of her everyday life as a young university lecturer in Taiwan. “It’s about living and managing in a foreign culture and returning home to the supposedly familiar, which you suddenly see with different eyes,” Hornfeck says.

A cat that she took over from friends helped her during this time. It was only supposed to take care of the ubiquitous rats on campus, but instead, it gave life advice with intuitive feline wisdom and gently nudged Hornfeck in the right direction again and again. Later, “Shaobai” – as the Taiwanese cat is actually called – had to learn how to adapt to a foreign culture herself. Hornfeck took it with her to Germany. Svenja Napp

Kevin Schwenk took over the position of Liaison Manager China at Afag Group this month. The Swiss-based company supplies components for assembly automation. The trained industrial mechanic and team leader in internal sales will perform his new duties from Locherhof in Germany.

Hu Xeyi, former chairman of Beijing carmaker BAIC, is the subject of corruption investigations by the CCP. BAIC is a production partner of Mercedes-Benz.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

At work, we pitch projects using fancy powerpoints, juggle millions, create trend-setting analyses. And at home? We are reduced to poop shoveling officials by our pets.

China’s linguistic acrobats have long since faced this reality and packaged it in the charming term of 铲屎官 chǎnshǐguān, lately a tongue-in-cheek synonym for “pet owner”. The ironic self-title is composed of the characters 铲 chǎn “shovel” or “shovel, shovel, spade”, 屎 shǐ “excrement, dung, shit” and 官 guān “civil servant”. Poop shoveling public servants are thus primarily responsible for the state-bearing task of shoveling away, picking up and bagging up pet poop.

Let’s not fool ourselves: We may think we are the masters of our beloved four-legged friends in fits of arrogance and megalomania. But when our furry friends leave a pile we need to clean up, we are instantly brought back down to the ground. Charmed by cute woof-woofs and meows, we willingly allow ourselves to be instrumentalized for all kinds of menial tasks. By the way, new Chinese also has a fitting term for this: the “tool person”, pronounced 工具人 gōngjùrén. For our pets, we are mainly used as can openers and fur-scratching machines at the end of the day.

Keywords such as “mutt excrement cadre” or “kitty poop manager” also lead us straight to a range of topics that are usually given a wide berth in Chinese lessons: shitology. Unjustly, in my opinion! For one thing, everything that goes in must come out again at some point. But more importantly, dealing with seemingly less-than-pleasant foreign words can be an entertaining and enlightening experience, at least in Mandarin. So let us delve deep into intercultural poop insights!

The dictionary defines “poop” as solid human excretion. If one wants to express oneself more specifically in China (e.g. at the doctor’s), number two should be called 大便 dàbiàn (literally “big convenience” – from 大 dà “big” and 方便 fāngbiàn “effortless, convenient, practical”). The number one is logically called “small convenience” (小便 xiǎobiàn). If you want to go to the bathroom tactfully, it is best to say 我去方便一下 wǒ qù fāngbiàn yíxià, meaning “I’m going to relieve myself” (literally, “I’m going to make myself comfortable”). But in the end, no one really wants to know.

As we have already seen, number two can be named straight away with the Hanzi 屎shǐ. That’s right. In Chinese, poop also has its own character, a very succinct one at that. 屎 is made up of the phonetic component 尸 shī, which actually means corpse, and 米 mǐ for “(husked) rice”. Rice that comes out of a body, so to speak – that sums things up quite well in a few brushstrokes.

Meanwhile, the ordinary version of defecate is 拉屎 lāshǐ, from 拉 lā “(to) pull out”. Perhaps better memorized simply as the Chinese version of “to take a dump”. Incidentally, the word 拉屎 lāshǐ also appears in some pleasant idioms. For example, in 鸡不生蛋狗不拉屎 jī bù shēngdàn gǒu bù lāshǐ, literally “where chickens don’t lay eggs and dogs don’t shit”, or “the arse end of the world”. Or also in the expression 占着茅坑不拉屎 zhànzhe máokēng bù lāshǐ, “to occupy the toilet and not to shit”, which, depending on the context, means either “spoilsport” or the bad habit of idly and incompetently blocking a post without letting more suitable candidates take over.

The character 屎 is worth remembering anyway, as it conveniently combines many other words that our body naturally secretes and excretes every day. For example, “nasal manure” (鼻屎 bíshǐ – Chinese for boogers), “ear shit” (耳屎ěrshǐ – ear wax) and “eye shit” (眼屎 yǎnshǐ – sleepy-seeds, sleepies).

Thanks to the already-mentioned poop vocabulary, you will certainly quickly figure out the riddle of what the character 尿 is all about. This time, something liquid is obviously going into the bowl, indicated by the component 水 shuǐ “water”. Correct: 尿, pronounced niào, is the hanzi for “urine” or even “to urinate.” In the vernacular, it also appears in the variants 尿尿 niàoniào “to pee” or 撒尿 sāniào “to pee” (literally actually “to scatter urine”).

If you really want to upset your fellow Chinese while standing in line at the toilet, just round your lips cheerfully and start a constant, monotonous continuous whistling tone. For many Chinese, this acoustic trigger pushes directly on the bladder, so that there is almost no holding back. This is because Chinese parents whistle to encourage their little ones to tinkle, whenever they are taking their sweet time. This seems to have etched itself deeply into people’s acoustic memory, like a Pavlovian pee whistle, even into adulthood.

Fortunately, the offspring can manage without fixed pee times if they are strapped into a diaper. Colloquially, this has the wonderful name 尿不湿 niàobùshī, which translates roughly as “does not get wet when peeing” (尿 niào = pee, 不 bù = not, 湿 shī = wet, moist). Another ingenious invention in this context are Chinese slit pants, which sometimes make foreigners smirk during their first visits to Chinese rural areas. In the case of these baby or toddler pants, the material that could get wet in the worst case was simply left out, namely the crotch. Problem solved. In Chinese, the underpants are simply called 开裆裤 kāidāngkù – “pants with open crotch”.

Even for us adults, the bladder sometimes squeezes at the wrong time, for example at the movies or during shows. Unfortunately, this usually happens just when things are getting exciting. Conversely, there are also sometimes dramaturgical lulls, i.e. dull parts that are only good for a bathroom break. China’s youth has therefore christened such boring scenes and sequences simply 尿点 niàodiǎn, i.e. “pee points” or “pee times”. Other “points” in the linguistic timeline would be the “tear point” (泪点 lèidiǎn – meaning a particularly touching scene) or the “laugh point” (笑点 xiàodiǎn – a funny scene or punch line).

But let’s get back to the restroom. In Mandarin, it is called 厕所 cèsuǒ (“toilet”). And in China, people also go to the bathroom (上厕所 shàng cèsuǒ – from 上 “to go, to go up”). Somewhat more refined variations of the word would be the “hand-washing room” (洗手间 xǐshǒujiān) or the “hygiene room” (卫生间 wèishēngjiān). However, the crucial question facing all bathroom-goers in the Middle Kingdom is: squat or sit? Because in public places like airports or shopping malls, you usually have the choice between squat toilets (蹲坑厕所 dūnkēng cèsuǒ or 坑 kēng for short, literally “pit”) or the so-called “horse bucket” (马桶 mǎtǒng), which is the Chinese name for our Western toilet bowl. While many Chinese have long since discovered the advantages of the seated toilet in their own homes, and even luxury versions based on the Japanese model (with heated seat and massage jet) are selling like hotcakes in the new middle class, many still prefer the classic squat toilet in public toilets, mostly for hygienic reasons.

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.