A heated debate about academic collaboration with China has flared up, and not just since German Minister of Education and Research Stark-Watzinger warned that the Chinese Communist Party could be hiding behind every Chinese researcher. However, there is a middle way between the general suspicion of espionage and overly naïve cooperation. Tim Gabel and Felix Lee spoke with DAAD President Joybrato Mukherjee about what profitable cooperation with China could look like.

Mukherjee believes cooperation with the People’s Republic must be expanded, but with careful examination of content and people. At the same time, however, he says it is necessary to become less dependent on Chinese funding. Mukherjee sees the first signs of this in the German government’s China strategy. Nevertheless, the DAAD President warns that the strategy will fail in its current implementation.

It cannot be denied that China has long since become one of the leading scientific nations – despite increasingly totalitarian structures. The People’s Republic of China has thus turned established theories on their head, notes Marcel Grzanna.

This is because the social environment in China is extremely unusual for a top research nation. Some research goals are dictated by the state. The scientific community seeks solutions with a great deal of pragmatism. Grzanna’s article examines the factors that have favored China’s advancement in research – and where potential problems and risks lie.

The German government is cutting funding for China programs. Private foundations, which had extensive programs not long ago, have also reduced their funding. Yet, at the same time, the government’s coalition agreement and China strategy call for more China expertise. Does this fit together?

We cannot confirm that China programs are being extensively slashed everywhere. As far as the DAAD portfolio is concerned, we are discussing the viability of individual funding projects with the BMBF (Federal Ministry of Education and Research), for example. For instance, Bielefeld University of Applied Sciences wants to set up an independent branch in the People’s Republic on the southern Chinese island of Hainan. We are in intensive talks about such individual projects. But no one has approached us with the intention of fundamentally slashing China programs. What is clear, however, is that we need to explain more clearly why we are doing what with China and in what way. I think that’s the right thing to do.

Are there any DAAD China projects that you think should be reconsidered?

Our transnational education projects are open to cooperation with all countries worldwide. Nevertheless, we will have to take a closer look at what happens in the respective projects regarding research work and the teaching of educational content in German university courses, and what may be risky or even harmful to us. As far as the aforementioned Bielefeld project is concerned, for example, it currently focuses exclusively on developing joint Bachelor’s degree programs. It does not include research components, so there is no need to worry about a technology drain. We, therefore, do not need to intervene here, at least as long as the Chinese side honors its promises regarding autonomy and academic freedom.

But what about the China Scholarship Council’s scholarship program, which is specifically funded by the Chinese government and promoted by the DAAD?

Indeed, we need to look very closely at how we admit CSC scholarship holders to German universities and what review procedures we need to implement, especially before they are accepted into research teams. The prerequisite for such procedures is, of course, that we at the universities have a clear overview of which Chinese doctoral students are here. Many German universities are already sensitized to this. However, it should be less about the contrast: Leave everything as it is versus we discontinue everything. Instead, a differentiated approach should be used to weigh up the opportunities and risks while ensuring that we can continue to work with China.

The University of Erlangen no longer admits CSC doctoral students, and the German research minister advises other universities to do the same. However, these scientists make up only a fraction of the 37,000 Chinese students in Germany. Isn’t this mere political symbolism?

First of all, the University of Erlangen does not intend to exclude CSC scholarship holders permanently. The aim is to establish a sustainable assessment procedure. And if this assessment comes to a positive conclusion, scholarship holders can be admitted. As long as this assessment procedure does not yet exist, a moratorium applies at the university. My colleague Joachim Hornegger (President of FAU Erlangen, editor’s note) explicitly did not intend to say that no more CSC scholarship holders should ever be allowed to attend the University of Erlangen. It’s about finding an intelligent way to implement a procedure so that you have the aforementioned overview of who is a scholarship holder at your own university and under what supervision.

You have recently become the new Rector of the University of Cologne. Will you handle things there like your colleague?

Yes, we have agreed internally that we want to gain an overview of the current CSC scholarship holders. I will also discuss with the dean’s offices that we develop a procedure for conducting a check or preliminary assessment of scholarship holders before admission. Given the changed geopolitical situation, we have a special obligation.

The Chinese system has been repressive for decades. Yet only now do people seem to be paying closer attention to who they are collaborating with. Have German researchers been naive in the past?

The fact that academia is much more vigilant regarding research collaboration with China is not directly dictated by politics. We have academic freedom and the autonomy of academic institutions. We rightly value this. In recent years, we have learned in the scientific community that it is crucial to adhere to common rules when collaborating with China. Since 2009, as President of the University of Giessen, I have also witnessed how collaboration with our Chinese partners has become more challenging, for example, with regard to unfulfillable genetic engineering requirements or excessive prerequisites for joint publications. Of course, this is not acceptable. However, the accusation that we were all naive before and only now have we all woken doesn’t do us justice.

However, both Jeffrey Stoff’s report and various journalistic investigations that have uncovered military-related collaborations suggest that self-regulation was not always effective enough in the past.

I would label this as a learning process. Today, the Chinese side acts differently than it did 10 or 20 years ago. In this context, I recommend the book “The Long Game” by Rush Doshi. Here, you can read about how China’s strategic goals have been disguised for a long time. This has been part of the Chinese strategy. And things that were successfully concealed could not be recognized. This is not a sign of naivety. Instead, over the last few years, we have seen a process of realization in society as a whole, in politics, but, of course, also in business and science.

Scientists in the fields of technology and natural sciences, in particular, are currently calling for intensified collaboration. This is because the Chinese side is now the leader in some areas. Shouldn’t we be siphoning off knowledge from China by now?

You point to something that we perhaps need to realize much more in the political sphere than science itself: We in Europe and North America are no longer in an unqualified position of strength. The unipolar moment of the early 1990s is long gone. China is now a leader in some research areas. Therefore, It is our interest to benefit from the sometimes very strong research groups in China. If we isolate ourselves, we will harm ourselves. That is why a differentiated, equally interest-led and risk-conscious approach is appropriate.

Shouldn’t we be intensifying our collaboration with China even more? The Americans have chosen China as their great rival and are pumping more money into building up China expertise than ever before. In Germany, there seems to be an opposite reflex. The more complicated the situation, the more we withdraw.

Yes, we clearly need to build up much more China expertise. The last chapter of the German government’s China strategy is about nothing else. And yes, as far as China expertise is concerned, we are in a worse position than the United States, for example. There are also fields in which there are no dual-use risks. For instance, there has been a very successful center for German studies between Berlin universities and Peking University for many years. Young people from China and Germany meet there. And that is also rightly the aim of the China strategy, namely bringing the young generation closer together through exchange programs.

Many universities lack the human and financial resources to make balanced decisions on research collaborations. This is what the employees of China centers tell us.

There is no doubt that the additional costs arising from such procedures, which need to be implemented, must become part of the fundamental structures and are, therefore, part of the basic funding of German universities. Our universities are underfunded in this respect. We need to talk about many things that German universities will need in the future and that are actually part of basic funding.

Would it relieve the burden on universities if the federal states or the federal government were to create decision-making bodies? Do we need state supervision? The Netherlands is giving this a lot of thought.

No institution outside a university will be able to make extensive decisions for a university. This is also unthinkable under our concept of autonomy. However, the academic freedom of individual academics enshrined in the German Basic Law is not unlimited. We are obliged by law not to authorize certain things. However, decisions must be made independently at each university. Regardless of this, external advice is valuable and important.

A central point of contact would have the advantage of not having many different decision-making channels and views.

For the academic sector, we offer precisely this central point of contact with our “Competence Centre for International Scientific Cooperation,” or KIWi for short. We were promised in the spring that the BMBF would once again increase our funding for the KIWi team, for which I am incredibly grateful. And it is precisely this team that is available for “one-on-one” counseling. So, if a university now has a cooperation agreement with China and needs advice on problematic aspects, our colleagues at the KIWi are ready to assist. However, what KIWi cannot do – and what no one else can do either – is to make the decisions for the universities.

What about the now highly controversial Chinese-funded Confucius Institutes in Germany?

Our position is quite simple: The 17 universities that still operate a Confucius Institute and want to build up Chinese expertise should be urgently made the offer to transfer the Confucius Institutes into centers that are paid for with German taxpayers’ money.

Will the Chinese side go along with this?

It doesn’t have to. China can continue to run its Confucius Institutes. Our aim is to use German taxpayers’ money to independently develop China expertise. If we want to become free of Chinese influence, we must make ourselves independent of Chinese funding. This is actually a straightforward logic.

There are fewer and fewer researchers specializing in China and the number of students is also grossly disproportionate. This also does not lead to more China expertise?

Before the pandemic, there were around 8,000 German students in China, but this has rapidly decreased due to the pandemic. Now, there are about 1,700, and even after the pandemic, China remains relatively isolated. Meanwhile, around 37,000 Chinese students and doctoral candidates are in Germany. But that only makes up ten percent of the 370,000 international students here. When they go to Australia, the UK or the USA, they are on a completely different scale. So we don’t have such dependencies – we are much more diversified. But of course, if we only ever define our relationship with China in terms of what we no longer want to do, what we no longer want to be, then we won’t find anyone who is interested in learning the Chinese language and engaging with Chinese culture. And then we could set up hundreds of China competence centers and cultural institutes. They won’t do us any good if there is no interest in them.

And what are your suggestions on how to get young people interested?

I am a big fan of the German government’s new China strategy. It clearly states that it wants to promote exchange between young academics and interest in the respective culture. After all, Chinese culture is not just the Communist Party. We shouldn’t take such a simplistic view of the world. China has many other facets. We have to find intelligent ways to spark interest in them. And not because international understanding is cool, but because engaging with China is in our own national interest.

As a fan of the China strategy, what makes you optimistic that the implementation and results will be successful?

My biggest criticism of the China strategy is that it says on page 1 that implementation should not cost anything. If the strategy is taken politically seriously – and I have no doubt that it is – it will not be possible to fulfill this. I wish the German government would really go the extra mile and launch a large-scale program to build up expertise on China. We all see the need and the necessity to make ourselves more independent of the Confucius Institutes. I believe the spirit of the China strategy is fundamentally sound: A differentiated approach based on our own interests, but not a general rejection of collaboration with China.

Joybrato Mukherjee has been Rector of the University of Cologne since October 1, 2023. Prior to that, he was President of Justus Liebig University Giessen. He has been President of the German Academic Exchange Service since 2020.

For a few decades, the democratic world was quite certain: Only social freedom allows science to flourish like a tropical climate allows rainforest vegetation to grow. Autocracy, on the other hand, according to the prevailing view, is doomed to fail in its endeavors to create ground-breaking knowledge.

This conviction was well founded, based on the ideas of sociologist Robert K. Merton: universalism, equality, altruism and skepticism were the ingredients for achieving scientific milestones. Merton was sure that only democratic societies could provide these ingredients.

But with the rise of the People’s Republic of China to the top group of global scientific nations, Merton’s social theory is beginning to crumble. After all, none of the essential prerequisites for thriving research are present in pure form in China, some not even remotely.

With its growing importance in the international research community, China challenges common assumptions. Abundant data sources, relevant publishing, state-of-the-art research centers, internationally renowned award ceremonies – all this could shift more and more to China if the country manages to become the world’s leading scientific nation.

“A lot has changed. China is shaking the foundations of global science structures,” says Anna Lisa Ahlers. She heads the “Research Group China in the Global System of Science” of the Lise Meitner Program at the Max Planck Society (MPG). To find out how this is even possible, the Meitner Group is taking a close look “at the social structures on which science is based in China.” It will continue to examine the humanities and social sciences until 2025, as well as agricultural and climate issues and debates on the use and development of artificial intelligence.

Part of the group researches the theoretical approach of Chinese regional studies to find out how significant China’s role as an intellectual actor on a global level really is. At best, the five-year research program will provide a clear picture of the success factors. “We aim to understand how the scientific structures in China have developed and what influence the social environment has on research in the country,” says Ahlers.

China’s social environment is highly unusual for a top research nation. The state partly formulates research objectives in China. The scientific community is pragmatic in its search for solutions. China researcher Ahlers recognizes that the scientific community has become much more cautious since Xi Jinping became head of the Communist Party. The resulting questions are: Does a scientist reveal what he has researched? Do they present their theories to party cadres, or do they prefer to tell them what they want to hear? And how does this affect China as a research nation?

Under Xi’s predecessors, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin, researchers were given much greater autonomy in the 1990s and 2000s than today. But now, for example, the think tank landscape, which has flourished for years, is organized much more centrally. Think tanks are docked onto universities or local governments. Their work is much more focused. “Think tanks can no longer discuss everything that was once on the table. The information base for decision-making has become smaller,” says Ahlers.

The country has undoubtedly become more appealing to researchers from all over the world. Extensive third-party funding for research projects and state-of-the-art laboratories exert a certain attraction. The number of foreign scientists has increased. However, the Meitner Group has found that only very few want to stay in China in the long term. “It seems that China is becoming more appealing, but only up to a certain point,” says Ahlers.

Problems such as air pollution or the circumstances of family life keep many foreigners from making a long-term commitment to the People’s Republic. These issues are so crucial to foreign researchers that even large budgets and cutting-edge equipment do not offer enough prospects to retain guest researchers. The handling of the pandemic has also made many guests in China realize that their foreign citizenship does not help them escape the iron grip of the state during a crisis.

Under these circumstances, the state’s portrayal of the existence of a Chinese model does not yet pass the reality test. Although China is working to develop a strong profile in the scientific community, international ties remain a core component of Chinese science, according to Ahlers.

However, in recent years, Chinese students have indeed tended to stay in China. The pandemic has played a role in this, as have growing geopolitical tensions between the People’s Republic and the West. The increasing quality of Chinese education also compels many students to pursue less expensive studies at home. It remains to be seen what impact these developments will have in the long term.

EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has warned against an overly naive approach when dealing with Beijing. “We must recognize that there is an explicit element of rivalry in our relationship. The Chinese Communist Party’s clear goal is a systemic change of the international order, of course with China at its center,” she said at the EU Ambassadors Conference on Monday. Von der Leyen also addressed the wars in Ukraine and Israel in her speech. However, China took up a similar amount of time in her speech.

The rivalry with the People’s Republic “can be constructive, not hostile,” von der Leyen continued. “And this is why we need functioning channels of communication and high-level diplomacy.” She announced the EU-China summit in December. The EU Commission President criticized China for not distancing itself from Russia, but stressed: “The way forward is to keep engaging with Beijing so that the support to Russia remains as limited as possible.” At the same time, however, it must be made clear that China’s relationship with Russia affects the relationship between Beijing and Brussels.

Von der Leyen commended trade policy measures such as the investigation into subsidies for Chinese EVs and the EU’s Global Gateway infrastructure initiative. At the associated forum, “a number of impressive new projects across the world.” This week, EU Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton will travel to China and Hong Kong. In the meantime, Foreign Affairs Commissioner Josep Borrell will travel to Japan. ari

Large companies see considerable risks to their production in connection with the People’s Republic of China. According to a survey by the European Central Bank (ECB), around two-thirds of companies rate the country as a risk factor for their supply chains. According to the survey, around 40 percent purchased essential intermediate goods from China and rated this as an increased risk. The Bundesbank recently pointed out that German industry heavily depends on intermediate goods from China.

Almost all companies reported that they find it “difficult” or “very difficult” to replace intermediate goods from China. Around 40 percent stated they intend to source the same inputs from other countries outside the EU. 20 percent pursue a strategy of mainly sourcing such products from EU countries. Around 15 percent rely on extended warehousing or modified components of their products. According to the survey, just under 20 percent of companies have not yet developed a strategy, but intend to do so in the future.

In comparison: Only about ten percent of companies see risks for their supply chains in the USA, Taiwan, India, Turkey or Russia. rtr/grz

Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has spoken to China’s President Xi Jinping in favor of closer military cooperation between the People’s Republic and the United States. During his visit to Beijing, Albanese spoke with Xi about the global security situation and emphasized the importance of closer cooperation between the two nations. Albanese referred in particular to the war in Ukraine and the Gaza Strip.

Australia is a member of the Quad Group, a security and military policy alliance with the USA, India and Japan. Due to China’s growing military presence in the South China Sea and its rapprochement with island states in the South Pacific, Beijing’s military influence is increasingly advancing towards the Australian coast.

However, both sides sought to maintain a friendly atmosphere during the visit. China did not raise the list of “14 grievances” it had formulated against Australia in 2020. These 14 points were the result of a diplomatic dispute that culminated in trade disputes after Australia excluded the Chinese company Huawei from its 5G network and called for an international investigation into the origin of the Coronavirus.

At the time, Beijing criticized Australian institutions for allegedly being overly critical of China research or accusations of Chinese interference in Australian affairs. However, relations between the two countries have improved since Albanese took office in 2022. China has once again allowed more imports of Australian products. Last month, Beijing agreed to review its tariffs of 218 percent on Australian wine. grz

The EU Commission recognizes efforts by the short video platform TikTok to comply with the Digital Services Act (DSA) – but intends to examine them more closely. “We have seen changes on TikTok’s platform in the past months, with new features being released with the aim to protect users and investments made in content moderation and trust and safety,” Thierry Breton, the EU’s internal market commissioner, said, after a video call with TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew. The DSA is an EU law that regulates liability and safety rules for digital platforms, services and products, among other things.

The Commission is now investigating whether this is enough to ensure compliance with the DSA, which is designed to protect citizens from illegal content and disinformation. The Commission had already submitted a list of questions to TikTok. On X, TikTok’s policy advisor Theo Bertram noted that it had been a good meeting with Breton. “We continue to engage closely with the Commission on DSA compliance.,” Bertram announced. As in January, Chew will also meet the Commissioners for Digital Affairs, Věra Jourová, and Justice Commissioner Didier Reynders on the second day of his visit to Brussels.

Also on Monday, the Commission submitted a formal request for information under the DSA to the retail platform AliExpress. In it, the Commission asks AliExpress to provide more details on what the company has done to improve consumer protection against illegal products such as counterfeit medicines.

Breton said that the DSA not only deals with hate speech or disinformation. The law also intends to ensure that no illegal or unsafe products are sold on online trading platforms in the EU. AliExpress has to submit the required information to the Commission by November 27, 2023. vis

The official statement from the Chinese Central Commission for Discipline Inspection appears almost unremarkable: One sentence, just 61 characters long. But the content of the statement marks the abrupt end of an impressive career. Zhang Hongli, once a highly acclaimed top banker at Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank and later Vice President of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), is suspected of serious disciplinary and legal violations. For this reason, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CDDI) has initiated a corresponding investigation. In China, the wording means: Zhang Hongli is accused of corruption. Experience shows that his chances of being cleared of the charges are close to zero.

Zhang is best known for his time as Senior Executive Vice President of the state-owned ICBC – the world’s largest lender in terms of assets – from 2010 to 2018. It is one of the “Big Four” in the Chinese banking sector – alongside China Construction Bank, the Bank of China and the Agricultural Bank of China.

Zhang was born in 1965. After studying at Heilongjiang University, he obtained a Master’s degree from the University of Alberta (Canada) and an MBA from the University of California (USA). Zhang stayed in America and began his professional career as a finance executive at the headquarters of Hewlett-Packard.

After three years at the American IT company, he became a board member of the British Schroders International Merchant Bank and its China Sales Manager in July 1994. In June 1998, he made the next career leap to the investment banking giant Goldman Sachs. There, Zhang became Executive Director for Asia and chief representative of the Beijing office.

In March 2001, Zhang joined Deutsche Bank’s investment banking department, became Head of Greater China Branch in Asia, Vice Chairman and Chairman of China Region and President of Asia Region. In April 2010, he then moved to the ICBC. According to Chinese media, this made Zhang the first banker from a foreign bank to take on a senior position at one of China’s state-owned banks.

He also joined the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a high-level advisory body of the National People’s Congress. At the time, ICBC praised Zhang for his international experience and knowledge of the global financial markets. In 2018, he left the bank for family reasons and then joined the private equity group Hopu Investment as co-chair.

Zhang Hongli is the next former top executive from the Chinese banking sector to be prosecuted by the powerful disciplinary inspectorate. This year alone, more than 100 officials and executives have been prosecuted in the wake of President Xi Jinping’s extensive anti-corruption campaign. These include well-known bankers with whom Zhang Hongli had dealings during his time at ICBC, such as Li Xiaopeng from the China Everbright Group and Cong Lin from China Renaissance Holdings. Both are currently in custody.

Experts agree that the extensive campaign is not only intended to maintain financial stability and curb widespread corruption in China. Instead, President Xi also uses the instrument to repeatedly eliminate his opponents and rivals and thus further consolidate his own power. Michael Radunski

He Lifeng has been appointed Head of the Office of the Central Financial Commission (CFC). He has also been appointed as party chief of a separate Central Financial Work Commission (CFWC), which has been set up to strengthen the ideological and political role of the party in China’s overall financial system.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

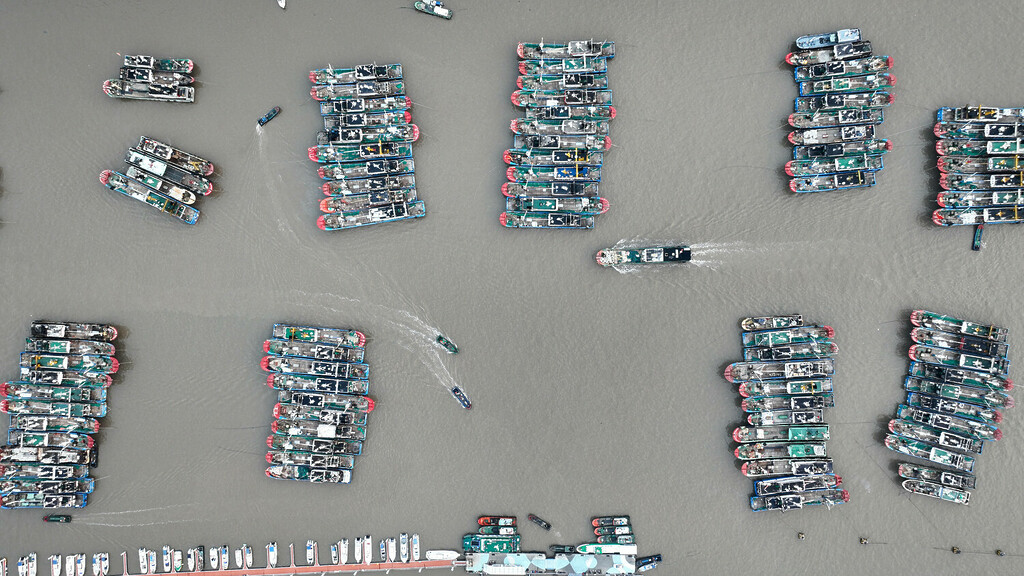

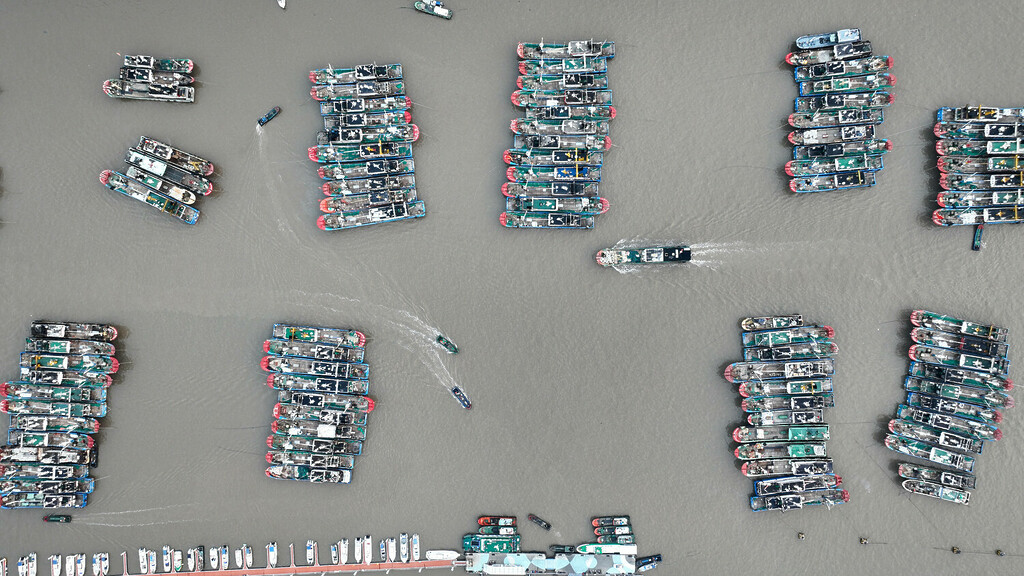

Like penguins bracing themselves against the cold, fishing boats offer each other protection from strong winds in the port of Zhoushan in the province of Zhejiang. The grouping of several boats, which are tightly secured to each other, reduces the risk of capsizing. Strong winds or typhoons regularly hit the east coast of the People’s Republic.

A heated debate about academic collaboration with China has flared up, and not just since German Minister of Education and Research Stark-Watzinger warned that the Chinese Communist Party could be hiding behind every Chinese researcher. However, there is a middle way between the general suspicion of espionage and overly naïve cooperation. Tim Gabel and Felix Lee spoke with DAAD President Joybrato Mukherjee about what profitable cooperation with China could look like.

Mukherjee believes cooperation with the People’s Republic must be expanded, but with careful examination of content and people. At the same time, however, he says it is necessary to become less dependent on Chinese funding. Mukherjee sees the first signs of this in the German government’s China strategy. Nevertheless, the DAAD President warns that the strategy will fail in its current implementation.

It cannot be denied that China has long since become one of the leading scientific nations – despite increasingly totalitarian structures. The People’s Republic of China has thus turned established theories on their head, notes Marcel Grzanna.

This is because the social environment in China is extremely unusual for a top research nation. Some research goals are dictated by the state. The scientific community seeks solutions with a great deal of pragmatism. Grzanna’s article examines the factors that have favored China’s advancement in research – and where potential problems and risks lie.

The German government is cutting funding for China programs. Private foundations, which had extensive programs not long ago, have also reduced their funding. Yet, at the same time, the government’s coalition agreement and China strategy call for more China expertise. Does this fit together?

We cannot confirm that China programs are being extensively slashed everywhere. As far as the DAAD portfolio is concerned, we are discussing the viability of individual funding projects with the BMBF (Federal Ministry of Education and Research), for example. For instance, Bielefeld University of Applied Sciences wants to set up an independent branch in the People’s Republic on the southern Chinese island of Hainan. We are in intensive talks about such individual projects. But no one has approached us with the intention of fundamentally slashing China programs. What is clear, however, is that we need to explain more clearly why we are doing what with China and in what way. I think that’s the right thing to do.

Are there any DAAD China projects that you think should be reconsidered?

Our transnational education projects are open to cooperation with all countries worldwide. Nevertheless, we will have to take a closer look at what happens in the respective projects regarding research work and the teaching of educational content in German university courses, and what may be risky or even harmful to us. As far as the aforementioned Bielefeld project is concerned, for example, it currently focuses exclusively on developing joint Bachelor’s degree programs. It does not include research components, so there is no need to worry about a technology drain. We, therefore, do not need to intervene here, at least as long as the Chinese side honors its promises regarding autonomy and academic freedom.

But what about the China Scholarship Council’s scholarship program, which is specifically funded by the Chinese government and promoted by the DAAD?

Indeed, we need to look very closely at how we admit CSC scholarship holders to German universities and what review procedures we need to implement, especially before they are accepted into research teams. The prerequisite for such procedures is, of course, that we at the universities have a clear overview of which Chinese doctoral students are here. Many German universities are already sensitized to this. However, it should be less about the contrast: Leave everything as it is versus we discontinue everything. Instead, a differentiated approach should be used to weigh up the opportunities and risks while ensuring that we can continue to work with China.

The University of Erlangen no longer admits CSC doctoral students, and the German research minister advises other universities to do the same. However, these scientists make up only a fraction of the 37,000 Chinese students in Germany. Isn’t this mere political symbolism?

First of all, the University of Erlangen does not intend to exclude CSC scholarship holders permanently. The aim is to establish a sustainable assessment procedure. And if this assessment comes to a positive conclusion, scholarship holders can be admitted. As long as this assessment procedure does not yet exist, a moratorium applies at the university. My colleague Joachim Hornegger (President of FAU Erlangen, editor’s note) explicitly did not intend to say that no more CSC scholarship holders should ever be allowed to attend the University of Erlangen. It’s about finding an intelligent way to implement a procedure so that you have the aforementioned overview of who is a scholarship holder at your own university and under what supervision.

You have recently become the new Rector of the University of Cologne. Will you handle things there like your colleague?

Yes, we have agreed internally that we want to gain an overview of the current CSC scholarship holders. I will also discuss with the dean’s offices that we develop a procedure for conducting a check or preliminary assessment of scholarship holders before admission. Given the changed geopolitical situation, we have a special obligation.

The Chinese system has been repressive for decades. Yet only now do people seem to be paying closer attention to who they are collaborating with. Have German researchers been naive in the past?

The fact that academia is much more vigilant regarding research collaboration with China is not directly dictated by politics. We have academic freedom and the autonomy of academic institutions. We rightly value this. In recent years, we have learned in the scientific community that it is crucial to adhere to common rules when collaborating with China. Since 2009, as President of the University of Giessen, I have also witnessed how collaboration with our Chinese partners has become more challenging, for example, with regard to unfulfillable genetic engineering requirements or excessive prerequisites for joint publications. Of course, this is not acceptable. However, the accusation that we were all naive before and only now have we all woken doesn’t do us justice.

However, both Jeffrey Stoff’s report and various journalistic investigations that have uncovered military-related collaborations suggest that self-regulation was not always effective enough in the past.

I would label this as a learning process. Today, the Chinese side acts differently than it did 10 or 20 years ago. In this context, I recommend the book “The Long Game” by Rush Doshi. Here, you can read about how China’s strategic goals have been disguised for a long time. This has been part of the Chinese strategy. And things that were successfully concealed could not be recognized. This is not a sign of naivety. Instead, over the last few years, we have seen a process of realization in society as a whole, in politics, but, of course, also in business and science.

Scientists in the fields of technology and natural sciences, in particular, are currently calling for intensified collaboration. This is because the Chinese side is now the leader in some areas. Shouldn’t we be siphoning off knowledge from China by now?

You point to something that we perhaps need to realize much more in the political sphere than science itself: We in Europe and North America are no longer in an unqualified position of strength. The unipolar moment of the early 1990s is long gone. China is now a leader in some research areas. Therefore, It is our interest to benefit from the sometimes very strong research groups in China. If we isolate ourselves, we will harm ourselves. That is why a differentiated, equally interest-led and risk-conscious approach is appropriate.

Shouldn’t we be intensifying our collaboration with China even more? The Americans have chosen China as their great rival and are pumping more money into building up China expertise than ever before. In Germany, there seems to be an opposite reflex. The more complicated the situation, the more we withdraw.

Yes, we clearly need to build up much more China expertise. The last chapter of the German government’s China strategy is about nothing else. And yes, as far as China expertise is concerned, we are in a worse position than the United States, for example. There are also fields in which there are no dual-use risks. For instance, there has been a very successful center for German studies between Berlin universities and Peking University for many years. Young people from China and Germany meet there. And that is also rightly the aim of the China strategy, namely bringing the young generation closer together through exchange programs.

Many universities lack the human and financial resources to make balanced decisions on research collaborations. This is what the employees of China centers tell us.

There is no doubt that the additional costs arising from such procedures, which need to be implemented, must become part of the fundamental structures and are, therefore, part of the basic funding of German universities. Our universities are underfunded in this respect. We need to talk about many things that German universities will need in the future and that are actually part of basic funding.

Would it relieve the burden on universities if the federal states or the federal government were to create decision-making bodies? Do we need state supervision? The Netherlands is giving this a lot of thought.

No institution outside a university will be able to make extensive decisions for a university. This is also unthinkable under our concept of autonomy. However, the academic freedom of individual academics enshrined in the German Basic Law is not unlimited. We are obliged by law not to authorize certain things. However, decisions must be made independently at each university. Regardless of this, external advice is valuable and important.

A central point of contact would have the advantage of not having many different decision-making channels and views.

For the academic sector, we offer precisely this central point of contact with our “Competence Centre for International Scientific Cooperation,” or KIWi for short. We were promised in the spring that the BMBF would once again increase our funding for the KIWi team, for which I am incredibly grateful. And it is precisely this team that is available for “one-on-one” counseling. So, if a university now has a cooperation agreement with China and needs advice on problematic aspects, our colleagues at the KIWi are ready to assist. However, what KIWi cannot do – and what no one else can do either – is to make the decisions for the universities.

What about the now highly controversial Chinese-funded Confucius Institutes in Germany?

Our position is quite simple: The 17 universities that still operate a Confucius Institute and want to build up Chinese expertise should be urgently made the offer to transfer the Confucius Institutes into centers that are paid for with German taxpayers’ money.

Will the Chinese side go along with this?

It doesn’t have to. China can continue to run its Confucius Institutes. Our aim is to use German taxpayers’ money to independently develop China expertise. If we want to become free of Chinese influence, we must make ourselves independent of Chinese funding. This is actually a straightforward logic.

There are fewer and fewer researchers specializing in China and the number of students is also grossly disproportionate. This also does not lead to more China expertise?

Before the pandemic, there were around 8,000 German students in China, but this has rapidly decreased due to the pandemic. Now, there are about 1,700, and even after the pandemic, China remains relatively isolated. Meanwhile, around 37,000 Chinese students and doctoral candidates are in Germany. But that only makes up ten percent of the 370,000 international students here. When they go to Australia, the UK or the USA, they are on a completely different scale. So we don’t have such dependencies – we are much more diversified. But of course, if we only ever define our relationship with China in terms of what we no longer want to do, what we no longer want to be, then we won’t find anyone who is interested in learning the Chinese language and engaging with Chinese culture. And then we could set up hundreds of China competence centers and cultural institutes. They won’t do us any good if there is no interest in them.

And what are your suggestions on how to get young people interested?

I am a big fan of the German government’s new China strategy. It clearly states that it wants to promote exchange between young academics and interest in the respective culture. After all, Chinese culture is not just the Communist Party. We shouldn’t take such a simplistic view of the world. China has many other facets. We have to find intelligent ways to spark interest in them. And not because international understanding is cool, but because engaging with China is in our own national interest.

As a fan of the China strategy, what makes you optimistic that the implementation and results will be successful?

My biggest criticism of the China strategy is that it says on page 1 that implementation should not cost anything. If the strategy is taken politically seriously – and I have no doubt that it is – it will not be possible to fulfill this. I wish the German government would really go the extra mile and launch a large-scale program to build up expertise on China. We all see the need and the necessity to make ourselves more independent of the Confucius Institutes. I believe the spirit of the China strategy is fundamentally sound: A differentiated approach based on our own interests, but not a general rejection of collaboration with China.

Joybrato Mukherjee has been Rector of the University of Cologne since October 1, 2023. Prior to that, he was President of Justus Liebig University Giessen. He has been President of the German Academic Exchange Service since 2020.

For a few decades, the democratic world was quite certain: Only social freedom allows science to flourish like a tropical climate allows rainforest vegetation to grow. Autocracy, on the other hand, according to the prevailing view, is doomed to fail in its endeavors to create ground-breaking knowledge.

This conviction was well founded, based on the ideas of sociologist Robert K. Merton: universalism, equality, altruism and skepticism were the ingredients for achieving scientific milestones. Merton was sure that only democratic societies could provide these ingredients.

But with the rise of the People’s Republic of China to the top group of global scientific nations, Merton’s social theory is beginning to crumble. After all, none of the essential prerequisites for thriving research are present in pure form in China, some not even remotely.

With its growing importance in the international research community, China challenges common assumptions. Abundant data sources, relevant publishing, state-of-the-art research centers, internationally renowned award ceremonies – all this could shift more and more to China if the country manages to become the world’s leading scientific nation.

“A lot has changed. China is shaking the foundations of global science structures,” says Anna Lisa Ahlers. She heads the “Research Group China in the Global System of Science” of the Lise Meitner Program at the Max Planck Society (MPG). To find out how this is even possible, the Meitner Group is taking a close look “at the social structures on which science is based in China.” It will continue to examine the humanities and social sciences until 2025, as well as agricultural and climate issues and debates on the use and development of artificial intelligence.

Part of the group researches the theoretical approach of Chinese regional studies to find out how significant China’s role as an intellectual actor on a global level really is. At best, the five-year research program will provide a clear picture of the success factors. “We aim to understand how the scientific structures in China have developed and what influence the social environment has on research in the country,” says Ahlers.

China’s social environment is highly unusual for a top research nation. The state partly formulates research objectives in China. The scientific community is pragmatic in its search for solutions. China researcher Ahlers recognizes that the scientific community has become much more cautious since Xi Jinping became head of the Communist Party. The resulting questions are: Does a scientist reveal what he has researched? Do they present their theories to party cadres, or do they prefer to tell them what they want to hear? And how does this affect China as a research nation?

Under Xi’s predecessors, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin, researchers were given much greater autonomy in the 1990s and 2000s than today. But now, for example, the think tank landscape, which has flourished for years, is organized much more centrally. Think tanks are docked onto universities or local governments. Their work is much more focused. “Think tanks can no longer discuss everything that was once on the table. The information base for decision-making has become smaller,” says Ahlers.

The country has undoubtedly become more appealing to researchers from all over the world. Extensive third-party funding for research projects and state-of-the-art laboratories exert a certain attraction. The number of foreign scientists has increased. However, the Meitner Group has found that only very few want to stay in China in the long term. “It seems that China is becoming more appealing, but only up to a certain point,” says Ahlers.

Problems such as air pollution or the circumstances of family life keep many foreigners from making a long-term commitment to the People’s Republic. These issues are so crucial to foreign researchers that even large budgets and cutting-edge equipment do not offer enough prospects to retain guest researchers. The handling of the pandemic has also made many guests in China realize that their foreign citizenship does not help them escape the iron grip of the state during a crisis.

Under these circumstances, the state’s portrayal of the existence of a Chinese model does not yet pass the reality test. Although China is working to develop a strong profile in the scientific community, international ties remain a core component of Chinese science, according to Ahlers.

However, in recent years, Chinese students have indeed tended to stay in China. The pandemic has played a role in this, as have growing geopolitical tensions between the People’s Republic and the West. The increasing quality of Chinese education also compels many students to pursue less expensive studies at home. It remains to be seen what impact these developments will have in the long term.

EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has warned against an overly naive approach when dealing with Beijing. “We must recognize that there is an explicit element of rivalry in our relationship. The Chinese Communist Party’s clear goal is a systemic change of the international order, of course with China at its center,” she said at the EU Ambassadors Conference on Monday. Von der Leyen also addressed the wars in Ukraine and Israel in her speech. However, China took up a similar amount of time in her speech.

The rivalry with the People’s Republic “can be constructive, not hostile,” von der Leyen continued. “And this is why we need functioning channels of communication and high-level diplomacy.” She announced the EU-China summit in December. The EU Commission President criticized China for not distancing itself from Russia, but stressed: “The way forward is to keep engaging with Beijing so that the support to Russia remains as limited as possible.” At the same time, however, it must be made clear that China’s relationship with Russia affects the relationship between Beijing and Brussels.

Von der Leyen commended trade policy measures such as the investigation into subsidies for Chinese EVs and the EU’s Global Gateway infrastructure initiative. At the associated forum, “a number of impressive new projects across the world.” This week, EU Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton will travel to China and Hong Kong. In the meantime, Foreign Affairs Commissioner Josep Borrell will travel to Japan. ari

Large companies see considerable risks to their production in connection with the People’s Republic of China. According to a survey by the European Central Bank (ECB), around two-thirds of companies rate the country as a risk factor for their supply chains. According to the survey, around 40 percent purchased essential intermediate goods from China and rated this as an increased risk. The Bundesbank recently pointed out that German industry heavily depends on intermediate goods from China.

Almost all companies reported that they find it “difficult” or “very difficult” to replace intermediate goods from China. Around 40 percent stated they intend to source the same inputs from other countries outside the EU. 20 percent pursue a strategy of mainly sourcing such products from EU countries. Around 15 percent rely on extended warehousing or modified components of their products. According to the survey, just under 20 percent of companies have not yet developed a strategy, but intend to do so in the future.

In comparison: Only about ten percent of companies see risks for their supply chains in the USA, Taiwan, India, Turkey or Russia. rtr/grz

Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has spoken to China’s President Xi Jinping in favor of closer military cooperation between the People’s Republic and the United States. During his visit to Beijing, Albanese spoke with Xi about the global security situation and emphasized the importance of closer cooperation between the two nations. Albanese referred in particular to the war in Ukraine and the Gaza Strip.

Australia is a member of the Quad Group, a security and military policy alliance with the USA, India and Japan. Due to China’s growing military presence in the South China Sea and its rapprochement with island states in the South Pacific, Beijing’s military influence is increasingly advancing towards the Australian coast.

However, both sides sought to maintain a friendly atmosphere during the visit. China did not raise the list of “14 grievances” it had formulated against Australia in 2020. These 14 points were the result of a diplomatic dispute that culminated in trade disputes after Australia excluded the Chinese company Huawei from its 5G network and called for an international investigation into the origin of the Coronavirus.

At the time, Beijing criticized Australian institutions for allegedly being overly critical of China research or accusations of Chinese interference in Australian affairs. However, relations between the two countries have improved since Albanese took office in 2022. China has once again allowed more imports of Australian products. Last month, Beijing agreed to review its tariffs of 218 percent on Australian wine. grz

The EU Commission recognizes efforts by the short video platform TikTok to comply with the Digital Services Act (DSA) – but intends to examine them more closely. “We have seen changes on TikTok’s platform in the past months, with new features being released with the aim to protect users and investments made in content moderation and trust and safety,” Thierry Breton, the EU’s internal market commissioner, said, after a video call with TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew. The DSA is an EU law that regulates liability and safety rules for digital platforms, services and products, among other things.

The Commission is now investigating whether this is enough to ensure compliance with the DSA, which is designed to protect citizens from illegal content and disinformation. The Commission had already submitted a list of questions to TikTok. On X, TikTok’s policy advisor Theo Bertram noted that it had been a good meeting with Breton. “We continue to engage closely with the Commission on DSA compliance.,” Bertram announced. As in January, Chew will also meet the Commissioners for Digital Affairs, Věra Jourová, and Justice Commissioner Didier Reynders on the second day of his visit to Brussels.

Also on Monday, the Commission submitted a formal request for information under the DSA to the retail platform AliExpress. In it, the Commission asks AliExpress to provide more details on what the company has done to improve consumer protection against illegal products such as counterfeit medicines.

Breton said that the DSA not only deals with hate speech or disinformation. The law also intends to ensure that no illegal or unsafe products are sold on online trading platforms in the EU. AliExpress has to submit the required information to the Commission by November 27, 2023. vis

The official statement from the Chinese Central Commission for Discipline Inspection appears almost unremarkable: One sentence, just 61 characters long. But the content of the statement marks the abrupt end of an impressive career. Zhang Hongli, once a highly acclaimed top banker at Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank and later Vice President of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), is suspected of serious disciplinary and legal violations. For this reason, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CDDI) has initiated a corresponding investigation. In China, the wording means: Zhang Hongli is accused of corruption. Experience shows that his chances of being cleared of the charges are close to zero.

Zhang is best known for his time as Senior Executive Vice President of the state-owned ICBC – the world’s largest lender in terms of assets – from 2010 to 2018. It is one of the “Big Four” in the Chinese banking sector – alongside China Construction Bank, the Bank of China and the Agricultural Bank of China.

Zhang was born in 1965. After studying at Heilongjiang University, he obtained a Master’s degree from the University of Alberta (Canada) and an MBA from the University of California (USA). Zhang stayed in America and began his professional career as a finance executive at the headquarters of Hewlett-Packard.

After three years at the American IT company, he became a board member of the British Schroders International Merchant Bank and its China Sales Manager in July 1994. In June 1998, he made the next career leap to the investment banking giant Goldman Sachs. There, Zhang became Executive Director for Asia and chief representative of the Beijing office.

In March 2001, Zhang joined Deutsche Bank’s investment banking department, became Head of Greater China Branch in Asia, Vice Chairman and Chairman of China Region and President of Asia Region. In April 2010, he then moved to the ICBC. According to Chinese media, this made Zhang the first banker from a foreign bank to take on a senior position at one of China’s state-owned banks.

He also joined the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a high-level advisory body of the National People’s Congress. At the time, ICBC praised Zhang for his international experience and knowledge of the global financial markets. In 2018, he left the bank for family reasons and then joined the private equity group Hopu Investment as co-chair.

Zhang Hongli is the next former top executive from the Chinese banking sector to be prosecuted by the powerful disciplinary inspectorate. This year alone, more than 100 officials and executives have been prosecuted in the wake of President Xi Jinping’s extensive anti-corruption campaign. These include well-known bankers with whom Zhang Hongli had dealings during his time at ICBC, such as Li Xiaopeng from the China Everbright Group and Cong Lin from China Renaissance Holdings. Both are currently in custody.

Experts agree that the extensive campaign is not only intended to maintain financial stability and curb widespread corruption in China. Instead, President Xi also uses the instrument to repeatedly eliminate his opponents and rivals and thus further consolidate his own power. Michael Radunski

He Lifeng has been appointed Head of the Office of the Central Financial Commission (CFC). He has also been appointed as party chief of a separate Central Financial Work Commission (CFWC), which has been set up to strengthen the ideological and political role of the party in China’s overall financial system.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Like penguins bracing themselves against the cold, fishing boats offer each other protection from strong winds in the port of Zhoushan in the province of Zhejiang. The grouping of several boats, which are tightly secured to each other, reduces the risk of capsizing. Strong winds or typhoons regularly hit the east coast of the People’s Republic.