The Chinese paper for peace in Ukraine continued to occupy the world over the weekend. The reaction from the West was mostly criticism and skepticism: China could not be an honest peace broker because of its proximity to Russia. This view is particularly widespread in Europe’s capitals.

So, is the paper useless? Not from the Chinese point of view. Sinologist Marina Rudyak explains the motives in an interview with Michael Radunski. China is certainly trying to exert a moderating influence on Russia; after all, it has a real interest in the end of the war and the numerous dilemmas it poses for China’s policy.

At the same time, Beijing is worried about a Russian collapse. Rudyak does not expect a complete turn away from Moscow. However, she considers it equally unlikely that China will actually supply weapons to Russia, even if there might have been attempts.

The actual addressee of the 12-point plan is perhaps not so much in Kyiv or Moscow, nor in Washington or Brussels. Rather, it is all the second-tier countries fed up with the power structures of the traditional superpowers. China strikes a nerve with them, as Frank Sieren analyzes. It is thus worthwhile for Beijing to woo them. Today, the non-aligned states make up the majority of the world, and are economically strong – and China wants to take their lead. Whether it will succeed is an open question.

We wish you a good start to the week.

China presented its eagerly awaited “Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis” last Friday. What are the important positive points in your opinion?

A positive aspect of China’s paper is definitely its clear rejection of nuclear escalation. In points 7 and 8, Beijing opposes the use of nuclear weapons, like it also opposes biological and chemical weapons. Beijing also firmly rejects the bombing of nuclear facilities. This is a strong signal, especially since China is a nuclear power itself.

What is disappointing about this position paper?

China’s rhetoric has unfortunately remained right along its previous lines. It is calling for an end to hostilities. That is good. However, China places the responsibility equally on Ukraine and Russia. Thus, again, there is no explicit naming of the fact that Russia has violated the borders of a sovereign state. What’s more, from the Chinese perspective, the West is responsible for setting the conditions for negotiations. China itself presents itself as neutral.

China’s paper is consistently met with skepticism in the West. Even Volodymyr Zelenskiy is cautious. The Ukrainian President says while he does not see a peace plan in it, he is ready for talks.

It is not surprising that almost everything from China is currently met with skepticism in the West because Beijing is simply too close to Russia’s side. But China could have changed that.

How?

If it had actually brought itself into play as a mediator. Unfortunately, China does not do this. Instead, Beijing simply states what it is in favor of and what it is against. Regrettably, China has not offered to play any constructive role.

But what did it do? What are China’s goals with this paper?

With this paper, China wants to position itself as an advocate of the Global South. It wants to show that it is addressing the major concerns of development and security. This is reflected in the demands for the resumption of Ukrainian wheat exports and securing international supply chains.

What can then be made of the Chinese initiative overall?

I think it has to be seen in the context of the other two papers that came out in the same week: China’s position paper against US global hegemony and China’s Global Security Initiative Concept Paper. With these papers, China is primarily concerned with international status and a signal to the Global South that China is a “responsible great power.” It opposes the US and, at the same time, wants to present itself as a global peace power.

Why does China fail to be impartial even in a supposed peace paper?

China is in an extremely difficult situation. In Beijing, there is concern that the Putin regime could collapse. In that case, they would have to fear that the next forces at the top would be much worse and far more unpredictable. If Ukraine were to win, Russia would drop out as an ally. In the worst case, Russia would even break apart – and then China would have a very severe problem on its borders. Not to mention that, without Russia, China would suddenly stand alone in the rivalry with the United States.

Are you saying that China has no choice but to pact with Russia?

No, it could certainly do otherwise. But China overlooks Europe in all this. Beijing believes Europe has no autonomy and is merely an appendage of the United States. In this way, Beijing fails to recognize that a positive influence on the Ukraine war would score massive points with the EU. Instead, it cynically accepts that the fighting in Ukraine will continue and that the attention of the United States will be tied up.

But ending the war would not necessarily mean the end for Putin. China, in particular, could try to show Putin a way out while saving face. But this would require critical talks with him.

I think that is what China is actually trying to do. It is striking that China’s paper does not call for an immediate end to the war but for the parties to begin negotiations. Thus China is calling for a slow process out of consideration for Putin.

What is the reason behind it?

That would be guesswork now, but what we do know is that Wang Yi went to Moscow, certainly with some kind of mediation offer. Presumably, Russia did not go for it. At least this would explain that there was only a position paper with known positions, and not – as actually expected – an initiative by Xi Jinping personally. The statement by Russia’s press that followed the position paper also speaks for this. Russia stuck to its line that the condition for negotiations would be “denazification” and full neutrality of Ukraine.

Almost simultaneously with China’s peace initiative, reports are circulating about possible arms deliveries to Russia. How does this fit together?

It is a difficult question, but it is possible that some military officers in the People’s Liberation Army interpreted the guidelines from headquarters a bit too creatively.

Without Xi’s knowledge?

Yes, both the balloon incident and the alleged arms deliveries to Russia do not appear to have been approved by the central government. Although it may seem otherwise, China’s political system is fragmented, and Beijing is often only informed about such things through the Western press. But I believe the military thought they could straighten things out through middlemen and front companies.

Now, at the latest, Xi will be aware. What will he do?

The people have certainly already been brought back in line.

Let’s go back to the Chinese peace paper. What should now be the reaction to China’s initiative?

China must continuously be pushed to exert a constructive influence on Russia and to push Russia to stop the fighting.

That means, as disappointing as the paper may be, it should be used as a starting point to push China to take further steps?

This paper should be taken seriously and China should be told clearly: This is not enough. It is not enough for China to position itself and urge others to engage constructively. China must finally engage constructively itself.

How could China be made to do this? What’s in it for Beijing?

Europe needs to make clear that Chinese mediation would make a huge, very positive contribution to the currently strained EU-China relations. Because this is something that China is keen to achieve.

Marina Rudyak is a sinologist and currently a Substitute Professor for China’s society and economy at the University of Goettingen.

The Global Security Initiative (GSI) and the 12-point paper on Ukraine arise from the same strategic spirit. They are indicative of China’s overriding calculation to become the focal point for the interests of all states that do not want to follow the US and EU agenda – and do not benefit from doing so.

The so-called non-aligned states make up the majority of the world, are economically strong, and challenge the minority of the West. China and also India, which has been non-aligned for decades, woo their partners despite all their difficulties with the prospect that the global South will be able to jointly decide in the future what is right and what is wrong.

The West, on the other hand, warns that the international world order is under attack and that everyone must stand together against Russia. Most recently, US Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen repeated this position last weekend at the G20 meeting. The ascenders’ response: This is not our world order, not our war.

This was evident in the UN General Assembly’s recent vote on the war. As expected, a majority of countries called for Russia to withdraw from Ukraine. But the second vote of the day revealed a second truth behind it. The international community rejected joint sanctions against Russia. More than 170 of 193 UN nations do not support the West’s wishes.

Only about 15 percent of the world’s population, representing 45 percent of economic power (NATO plus Japan and, to some extent, South Korea), have imposed sanctions on Russia, while 84 percent of the world’s population, representing 55 percent of economic power, think nothing of it. “The divide deepens,” the New York Times noted soberly last weekend. China knows how to use this situation to its advantage.

The means to that end, for now, is the GSI. 80 countries and organizations support it, Beijing says. This does not appear to be an exaggeration. At the center of this movement are hand-in-hand dictatorship China and democracy India. Both abstained from the UN vote.

Now, in addition, the Beijing 12-point paper for Ukraine comes into play. It may have disappointed many observers in the West. But not much more could be expected. “Grass does not grow faster if you pull it,” a Chinese proverb goes.

The call for a ceasefire and talks without preconditions is enormously popular among the majority of countries China wants to lead. While the peace plan is seen as a major disappointment in the West, it speaks to many countries. The West and Kyiv, on the other hand, are calling for Russia’s complete withdrawal from Ukraine as a precondition for peace talks.

The rising countries led by China emphasize one thing: We have no time pressure. The war is far away. The G20 final document only mentions “the war in Ukraine,” which “most members condemn,” and “the different positions” on the UN resolution. It is clear that the Western position can no longer be asserted in the G20 for the time being.

The emerging countries that support the GSI have a different view of the world than the West: First, there was the time of the relentless colonialism of the Europeans, especially the British Empire. This was followed by the struggle for world domination by the Soviet Union and the USA during the Cold War. Then came the US’s unilateral actions, including military ones, as the world’s most powerful state from the 1990s onward. And now Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. For the rising countries, these are similar patterns.

The question is whether the new world is as clear-cut as Beijing might like. The non-aligned states are just that: non-aligned – and do not want to be patronized by Beijing. As long as Beijing comes up with offers that strike a nerve, they are on board. In other situations, they will pull out again as they see fit.

This is where the drawbacks of the current initiatives and the Chinese strategy of wanting to be the voice of the non-aligned states become apparent:

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko will travel to Beijing tomorrow (Tuesday) for a state visit, according to the Chinese Foreign Ministry. He will be in China from February 28 to March 2 at the invitation of China’s leader Xi Jinping, Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying announced.

Lukashenko, a loyal ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, is expected to support Beijing’s 12-point position paper on the Ukraine war. Russian troops have been in Belarus since late 2021; parts of Russia’s attacks on Kyiv started from Belarusian territory. According to media reports, Lukashenko is in Beijing to strengthen his country’s economic cooperation with China. ck

A team from the US television network CNN has involuntarily witnessed an incident between a US jet and a Chinese fighter jet over the South China Sea. The US jet with reporters on board, was about 30 nautical miles from the Paracel archipelago when it received a radio warning: “American aircraft. Chinese airspace is 12 nautical miles. Not approach any more or you bear all responsibility.”

After that, a Chinese fighter jet armed with air-to-air missiles appeared next to the US aircraft and escorted them on the port side in phases just over 150 meters away, report the journalists, who also filmed the incident. According to the journalists, they could see the pilots looking at them.

“PLA fighter aircraft, this is US Navy P-8A,” the pilot of the US jet radioed back. “I have you off my left wing and intend to proceed west. I request that you do the same, over.” The Chinese did not respond and escorted the US plane for 15 more minutes before turning away. The incident is apparently nothing special nowadays. “I would say it’s just another Friday afternoon in the South China Sea,” Marine Commander in charge Marc Hines told the CNN team. The Paracel archipelago counts 130 small coral islands and reefs spread over 15,000 square kilometers of sea area and is disputed between China, Vietnam, and Taiwan. Beijing has de facto control of the islands. ck

German chemicals group Covestro plans to build a factory for thermoplastic polyurethanes (TPU) in Zhuhai in southern China. The plant will require investments “in the low three-digit million euro range” and will be the group’s largest TPU factory when completed, it said. Covestro said the construction will take place in three phases. The first phase will be completed in 2025, and the last will be launched in 2033, it said. Then, the capacity should be 120,000 metric tons of TPU per year, it said. TPU is a plastic material used in various consumer goods, including the soles of sports shoes, cell phone housings, and parts of IT equipment or automobiles, according to Covestro.

The new site is being built in the Zhuhai Gaolan Port Economic Development Zone in Guangdong Province and will cover an area of 45,000 square meters. It will also include an innovation center. “With this new TPU facility, we aim to take advantage of the expected rapid and high market growth of the TPU market worldwide, especially in Asia and China,” the company quoted Chief Customer Officer (CCO) Sucheta Govil. ck

In 2022, the number of published patents in China’s auto sector has risen sharply. The reason for this was mainly the intensified competition in the development of technologies for EVs and connected cars, Caixin reported on Friday. According to the report, some 362,200 patents related to the automotive industry were published, 13 percent more than in 2021, the financial magazine wrote, citing data from the China Automobile IP Utilization Promotion Center (CAIPUPC). The number of patents in the electric segment increased by the same amount and accounted for the largest share of the total at 21.4 percent.

The world’s largest battery manufacturer, Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL), is particularly eager to conduct research. With 1,205 patents, it filed 268 percent more than in the previous year. This puts CATL in first place in this segment, according to Caixin. Last year, CATL still held fourth place in this ranking. Rival SVOLT is in second place with 1,049 patents. Meanwhile, South Korean giant LG has massively expanded its research activities in China, as evidenced by a sharp increase in patent applications. ck

Chinese surveillance cameras are now coming under criticism in Bulgaria as well. Bozhidar Bojanov, a member of parliament from Bulgaria’s opposition Democratic Party, has announced that he will ask the State Agency for National Security to review new surveillance cameras made by the Hikvison company on public transport in the capital Sofia. “I am saying that through Chinese and Russian technology, which are potentially compromised, strategic activity – public transport in the capital – can be negatively affected,” Radio Free Europe quoted Bojanov’s blog as saying.

According to the report, the controversy in Bulgaria centers on weaknesses in the Hikvision cameras and concerns about a lack of oversight in the procurement of the cameras, which have been in service since 2020. The transit agency responded to a Radio Free Europe inquiry that it did not have the right to impose country of origin or specific brand restrictions or requirements on equipment manufacturers in contracts. The consortium said it was guided by “needs, reliability and safety” and not by country of origin or brand.

Hikvision is the world’s largest manufacturer of video surveillance equipment. The company has come under criticism in some countries for its ties to the Chinese military and its role in developing special technology to monitor and track Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang. The US issued sanctions against the company. In the EU, there are no official restrictions on Hikvision, but the European Parliament has removed equipment manufactured by the company from its buildings. There has also been criticism over lax privacy protections and glitches discovered by researchers in Hikvision cameras upon closer inspection. ck

“All knowledge and life experience goes into translating,” says Karin Betz. Her profession: she translates Chinese literature into German. She has already made significant works by Liu Cixin, Liao Yiwu, and the Chinese literature prize winner Mo Yan accessible to the German public.

She thinks that Chinese literature has struggled in Germany so far because of the expectations of the German readership, which often thinks in pigeonholes. “Chinese literature should either be political, in the sense of being critical of the government, or esoteric, or sound as Chinese as possible,” she says. “It is not simply read as literature.”

To make matters worse, Chinese censors are holding back some exciting topics and denying funding to modern authors. “Before they become successful, authors depend on government funding. Without it, certain voices won’t be heard.”

Betz studied sinology, philosophy, and politics in Frankfurt am Main, Chengdu, and Tokyo. During her first stays in China in the early 1990s, she traveled alone by train through the country – also to remote regions, Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia. “Getting to know the great differences in this country consciously and slowly, ethnically, geographically, politically and economically, but also linguistically, was crucial for me,” she says, looking back.

After earning her master’s degree, Betz worked in various professional positions, including in Japan. Unlike work in international exchange and in business, she found university life rather confining: “In my experience, there is unfortunately still too much specialist idiocy instead of synergy,” she says – instead she preferred to go her own way. As the youngest of five siblings, she already had the necessary grit.

Betz is currently working on a translation of poetic miniatures about cats by Yu Youyou, a young poet from Sichuan. At the same time, she is working on a complex science fiction novel by Han Song.

To be successful in her work, she considers involvement with other arts to be part of the equation. For more than 20 years, Betz has been dancing Tango Argentino and DJing. “It’s part of my craft,” she explains. “It’s not just about knowledge, but also about emotion. Dance and movement are a wonderful school for empathy, intuition, and imagination.” Svenja Napp

Sam Wu will become the new head of US carmaker Ford’s China business. Wu is to move up from his current position as Managing Director and Chief Operating Officer to the role of President and Chief Executive on March 1, Ford announced. Wu succeeds Anning Chen, who will leave the company on Oct. 1.

The Nobel Sustainability Trust Foundation has honored China’s special climate envoy Xie Zhenhua as one of three recipients of its sustainability award. The foundation, led by four members of the Nobel family, cited Xie’s contribution to climate change mitigation and building global cooperation for sustainable development as the reason for the honor. Xie Zhenhua had represented China at several COP climate conferences.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

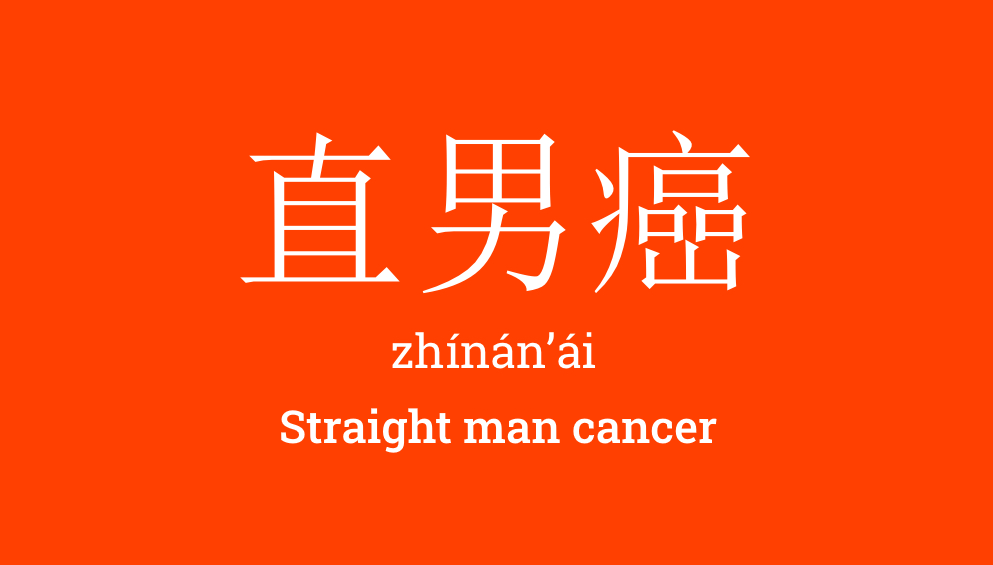

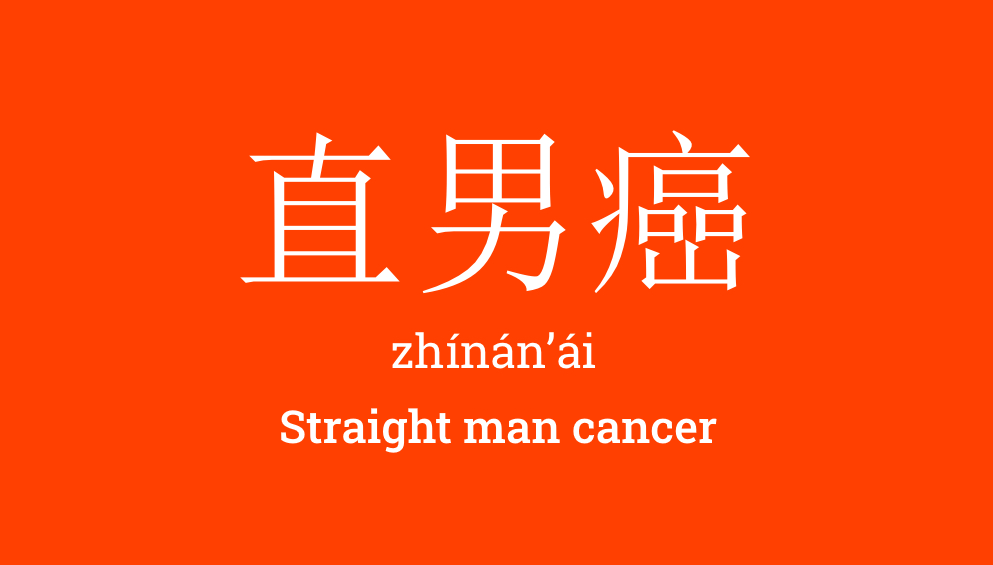

You think women belong in the kitchen? Hot pants and revealing cleavage provoke even the most prudish of men and women who wear them are therefore solely responsible for all consequences? MeToo is the devil’s work and a job for the exorcist to you? If so, you need to be strong now. Because your diagnosis is: straight man cancer, sadly it is terminal.

But let’s start from the beginning: 直男癌 zhínán’ái – “straight man cancer” – is an expression the Chinese use to describe machos and sexists. This neologism is a combination of the character for “cancer” (癌 ái, in the long form 癌症 áizhèng) and the Chinese expression for “heterosexual man” (直男 zhínán). The latter is literally taken from the English “straight man”, because 直 zhí means “straight, not curved”. The opposite in Chinese vernacular is consequently a “bent man” or “curved man”, namely the 弯男 wānnán, a “homosexual man”.

But let’s get back to the macho cancer. According to Chinese feminists (女权主义者 nǚquán zhǔyìzhě), this grows in the heads of men who can no longer be argued with and are therefore “beyond saving” (in Chinese: 没救 méi jiù). The cancer metaphor fits in perfectly with an already well-established linguistic recipe. Namely, the scolding phrase 你有病!Nǐ yǒu bìng! – “You have a disease!”. This is China’s equivalent of “You’re out of your mind” or “You’re a nutcase”. In this case, the patient is suffering from straight man cancer. Symptoms: An extremely sexist attitude coupled with exaggerated masculinity.

The mental macho tumor has a lot in common with the medical metaphor (at least in the eyes of those who use this expression). Macho cancer spreads rampantly and uncontrollably into all areas of mind and life and is a supposedly widespread disease among Y-chromosome owners. Unfortunately, curing attempts through feminist social media radiation therapy rarely yield the desired results. On the contrary, in China, they only seemed to fuel the formation of malignant masculinity metastases and the “gender war”. On the net, China’s macho men (大男子 dànánzǐ “macho, chauvinist”) verbally retaliated by coining the counterword “feminist cancer” (女权癌 nǚquán’ái), the Chinese equivalent of the English “feminazi”, a portmanteau of “feminist” and “Nazi”.

By the way, anyone who gets too involved in the debate – regardless of their chromosome type – runs the risk of becoming infected with another chronic affliction: misogyny or misandry. In Chinese internet terminology, this is also linguistically pathologized as “man-hating” or “woman-hating” syndrome (厌男症yànnánzhèng / 厌女症 yànnǚzhèng).

But while we’re at it, let’s enthusiastically beat the dust out of the cushions and look at what other male specimens could potentially take a seat on our linguistic therapy couch. In recent years, the Chinese internet vocabulary has developed a broad typology of creative expressions. The following is a selection of some highlights:

1. 普信男 pǔxìnnán – the average but over-confident man

This designation was coined by the feminist stand-up comedian Yang Li (杨笠 Yáng Lì) and has now become an established linguistic label. It refers to self-conscious men who ultimately have nothing going for them. All bark, no bite. Just as the Chinese expression says: an “average” (普 pǔ from 普通 pǔtōng “ordinary, mediocre”) but “over-confident” (信 xìn from 自信 zìxìn “self-confident”) man (男 nán).

2. 妈宝男 mābǎonán – the mama’s boy

Mum is the best, is always right, and in return pampers her offspring through and through even though he is a grown man? This description matches our mama’s boy perfectly, slightly modified in New Chinese to “mama’s sweetheart” (妈宝 mābǎo – from 妈 mā “mama” and 宝 bǎo “sweetheart”).

3. 凤凰男 fènghuángnán – the phoenix man

He has “risen from the ashes” and achieved greatness and glory in his adult life – the Phoenix Man (from 凤凰 fènghuáng “phoenix”). In China, this is the name given to men who, thanks to intelligence, hard work and a good education, worked their way up from humble to poor backgrounds and all the way to the top. Unfortunately, the memories from the past often catch up with these gentlemen, in the form of inferiority complexes. They then try to obsessively compensate for or cover up their inferiority complexes with a variety of quirks, both at work and in their personal lives. Another obvious case for the couch.

4. 软饭男 ruǎnfànnán – the man who lives off women.

This beau uses his charm to wrap wealthy ladies around his finger and to live off them. In Chinese, this is called “eating soft rice” (吃软饭 chī ruǎnfàn). So we are dealing with an opportunistic and submissive “soft rice gigolo” (软饭男 ruǎnfànnán).

5. 甘蔗男 gānzhènán – the sugar cane man

Do not fall for this sweetie! The sugarcane man pretends to be a softie – technically a “warmie” in Chinese (暖男 nuǎnnán for “softie, womanizer”). But he is actually a real “crumb man” (渣男 zhānán), an unfaithful pig. But what does that have to do with a sugar cane (甘蔗 gānzhè)? Well, those who have chewed on fresh sugar cane stalks – a popular summer street snack in China – know all about it: The first bites are sweet and juicy, only to soon leave you with crumbly, inedible fibers in your mouth that you have to spit out as soon as possible.

6. 画饼男 huàbǐngnán – the cookie artist guy

And last but not least: the biscuit artist guy. Marriage, car, apartment – this guy promises women the moon. But these are nothing but empty promises in the end, because the wannabe stud can’t keep them. In Chinese, such empty promises and unrealistic hopes are called “painting a cake” (also: drawing a sausage or flatbread – 画饼 huàbǐng). The corresponding type of man was therefore dubbed “cake painter” or “cookie artist guy” – 画饼男 huàbǐngnán – by the net community.

And which types of men roam around in your life? What you are missing now is probably a female typology guide. Of course, this could also be done for Chinese – but that is a story for another column.

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.

In China.Table number 529 last Friday, two figures in the chart on Silk Road trade were reversed. Saudi Arabia is the top recipient of investment with 30 billion US dollars, while Russia comes in second with 15 billion US dollars.

The Chinese paper for peace in Ukraine continued to occupy the world over the weekend. The reaction from the West was mostly criticism and skepticism: China could not be an honest peace broker because of its proximity to Russia. This view is particularly widespread in Europe’s capitals.

So, is the paper useless? Not from the Chinese point of view. Sinologist Marina Rudyak explains the motives in an interview with Michael Radunski. China is certainly trying to exert a moderating influence on Russia; after all, it has a real interest in the end of the war and the numerous dilemmas it poses for China’s policy.

At the same time, Beijing is worried about a Russian collapse. Rudyak does not expect a complete turn away from Moscow. However, she considers it equally unlikely that China will actually supply weapons to Russia, even if there might have been attempts.

The actual addressee of the 12-point plan is perhaps not so much in Kyiv or Moscow, nor in Washington or Brussels. Rather, it is all the second-tier countries fed up with the power structures of the traditional superpowers. China strikes a nerve with them, as Frank Sieren analyzes. It is thus worthwhile for Beijing to woo them. Today, the non-aligned states make up the majority of the world, and are economically strong – and China wants to take their lead. Whether it will succeed is an open question.

We wish you a good start to the week.

China presented its eagerly awaited “Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis” last Friday. What are the important positive points in your opinion?

A positive aspect of China’s paper is definitely its clear rejection of nuclear escalation. In points 7 and 8, Beijing opposes the use of nuclear weapons, like it also opposes biological and chemical weapons. Beijing also firmly rejects the bombing of nuclear facilities. This is a strong signal, especially since China is a nuclear power itself.

What is disappointing about this position paper?

China’s rhetoric has unfortunately remained right along its previous lines. It is calling for an end to hostilities. That is good. However, China places the responsibility equally on Ukraine and Russia. Thus, again, there is no explicit naming of the fact that Russia has violated the borders of a sovereign state. What’s more, from the Chinese perspective, the West is responsible for setting the conditions for negotiations. China itself presents itself as neutral.

China’s paper is consistently met with skepticism in the West. Even Volodymyr Zelenskiy is cautious. The Ukrainian President says while he does not see a peace plan in it, he is ready for talks.

It is not surprising that almost everything from China is currently met with skepticism in the West because Beijing is simply too close to Russia’s side. But China could have changed that.

How?

If it had actually brought itself into play as a mediator. Unfortunately, China does not do this. Instead, Beijing simply states what it is in favor of and what it is against. Regrettably, China has not offered to play any constructive role.

But what did it do? What are China’s goals with this paper?

With this paper, China wants to position itself as an advocate of the Global South. It wants to show that it is addressing the major concerns of development and security. This is reflected in the demands for the resumption of Ukrainian wheat exports and securing international supply chains.

What can then be made of the Chinese initiative overall?

I think it has to be seen in the context of the other two papers that came out in the same week: China’s position paper against US global hegemony and China’s Global Security Initiative Concept Paper. With these papers, China is primarily concerned with international status and a signal to the Global South that China is a “responsible great power.” It opposes the US and, at the same time, wants to present itself as a global peace power.

Why does China fail to be impartial even in a supposed peace paper?

China is in an extremely difficult situation. In Beijing, there is concern that the Putin regime could collapse. In that case, they would have to fear that the next forces at the top would be much worse and far more unpredictable. If Ukraine were to win, Russia would drop out as an ally. In the worst case, Russia would even break apart – and then China would have a very severe problem on its borders. Not to mention that, without Russia, China would suddenly stand alone in the rivalry with the United States.

Are you saying that China has no choice but to pact with Russia?

No, it could certainly do otherwise. But China overlooks Europe in all this. Beijing believes Europe has no autonomy and is merely an appendage of the United States. In this way, Beijing fails to recognize that a positive influence on the Ukraine war would score massive points with the EU. Instead, it cynically accepts that the fighting in Ukraine will continue and that the attention of the United States will be tied up.

But ending the war would not necessarily mean the end for Putin. China, in particular, could try to show Putin a way out while saving face. But this would require critical talks with him.

I think that is what China is actually trying to do. It is striking that China’s paper does not call for an immediate end to the war but for the parties to begin negotiations. Thus China is calling for a slow process out of consideration for Putin.

What is the reason behind it?

That would be guesswork now, but what we do know is that Wang Yi went to Moscow, certainly with some kind of mediation offer. Presumably, Russia did not go for it. At least this would explain that there was only a position paper with known positions, and not – as actually expected – an initiative by Xi Jinping personally. The statement by Russia’s press that followed the position paper also speaks for this. Russia stuck to its line that the condition for negotiations would be “denazification” and full neutrality of Ukraine.

Almost simultaneously with China’s peace initiative, reports are circulating about possible arms deliveries to Russia. How does this fit together?

It is a difficult question, but it is possible that some military officers in the People’s Liberation Army interpreted the guidelines from headquarters a bit too creatively.

Without Xi’s knowledge?

Yes, both the balloon incident and the alleged arms deliveries to Russia do not appear to have been approved by the central government. Although it may seem otherwise, China’s political system is fragmented, and Beijing is often only informed about such things through the Western press. But I believe the military thought they could straighten things out through middlemen and front companies.

Now, at the latest, Xi will be aware. What will he do?

The people have certainly already been brought back in line.

Let’s go back to the Chinese peace paper. What should now be the reaction to China’s initiative?

China must continuously be pushed to exert a constructive influence on Russia and to push Russia to stop the fighting.

That means, as disappointing as the paper may be, it should be used as a starting point to push China to take further steps?

This paper should be taken seriously and China should be told clearly: This is not enough. It is not enough for China to position itself and urge others to engage constructively. China must finally engage constructively itself.

How could China be made to do this? What’s in it for Beijing?

Europe needs to make clear that Chinese mediation would make a huge, very positive contribution to the currently strained EU-China relations. Because this is something that China is keen to achieve.

Marina Rudyak is a sinologist and currently a Substitute Professor for China’s society and economy at the University of Goettingen.

The Global Security Initiative (GSI) and the 12-point paper on Ukraine arise from the same strategic spirit. They are indicative of China’s overriding calculation to become the focal point for the interests of all states that do not want to follow the US and EU agenda – and do not benefit from doing so.

The so-called non-aligned states make up the majority of the world, are economically strong, and challenge the minority of the West. China and also India, which has been non-aligned for decades, woo their partners despite all their difficulties with the prospect that the global South will be able to jointly decide in the future what is right and what is wrong.

The West, on the other hand, warns that the international world order is under attack and that everyone must stand together against Russia. Most recently, US Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen repeated this position last weekend at the G20 meeting. The ascenders’ response: This is not our world order, not our war.

This was evident in the UN General Assembly’s recent vote on the war. As expected, a majority of countries called for Russia to withdraw from Ukraine. But the second vote of the day revealed a second truth behind it. The international community rejected joint sanctions against Russia. More than 170 of 193 UN nations do not support the West’s wishes.

Only about 15 percent of the world’s population, representing 45 percent of economic power (NATO plus Japan and, to some extent, South Korea), have imposed sanctions on Russia, while 84 percent of the world’s population, representing 55 percent of economic power, think nothing of it. “The divide deepens,” the New York Times noted soberly last weekend. China knows how to use this situation to its advantage.

The means to that end, for now, is the GSI. 80 countries and organizations support it, Beijing says. This does not appear to be an exaggeration. At the center of this movement are hand-in-hand dictatorship China and democracy India. Both abstained from the UN vote.

Now, in addition, the Beijing 12-point paper for Ukraine comes into play. It may have disappointed many observers in the West. But not much more could be expected. “Grass does not grow faster if you pull it,” a Chinese proverb goes.

The call for a ceasefire and talks without preconditions is enormously popular among the majority of countries China wants to lead. While the peace plan is seen as a major disappointment in the West, it speaks to many countries. The West and Kyiv, on the other hand, are calling for Russia’s complete withdrawal from Ukraine as a precondition for peace talks.

The rising countries led by China emphasize one thing: We have no time pressure. The war is far away. The G20 final document only mentions “the war in Ukraine,” which “most members condemn,” and “the different positions” on the UN resolution. It is clear that the Western position can no longer be asserted in the G20 for the time being.

The emerging countries that support the GSI have a different view of the world than the West: First, there was the time of the relentless colonialism of the Europeans, especially the British Empire. This was followed by the struggle for world domination by the Soviet Union and the USA during the Cold War. Then came the US’s unilateral actions, including military ones, as the world’s most powerful state from the 1990s onward. And now Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. For the rising countries, these are similar patterns.

The question is whether the new world is as clear-cut as Beijing might like. The non-aligned states are just that: non-aligned – and do not want to be patronized by Beijing. As long as Beijing comes up with offers that strike a nerve, they are on board. In other situations, they will pull out again as they see fit.

This is where the drawbacks of the current initiatives and the Chinese strategy of wanting to be the voice of the non-aligned states become apparent:

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko will travel to Beijing tomorrow (Tuesday) for a state visit, according to the Chinese Foreign Ministry. He will be in China from February 28 to March 2 at the invitation of China’s leader Xi Jinping, Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying announced.

Lukashenko, a loyal ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, is expected to support Beijing’s 12-point position paper on the Ukraine war. Russian troops have been in Belarus since late 2021; parts of Russia’s attacks on Kyiv started from Belarusian territory. According to media reports, Lukashenko is in Beijing to strengthen his country’s economic cooperation with China. ck

A team from the US television network CNN has involuntarily witnessed an incident between a US jet and a Chinese fighter jet over the South China Sea. The US jet with reporters on board, was about 30 nautical miles from the Paracel archipelago when it received a radio warning: “American aircraft. Chinese airspace is 12 nautical miles. Not approach any more or you bear all responsibility.”

After that, a Chinese fighter jet armed with air-to-air missiles appeared next to the US aircraft and escorted them on the port side in phases just over 150 meters away, report the journalists, who also filmed the incident. According to the journalists, they could see the pilots looking at them.

“PLA fighter aircraft, this is US Navy P-8A,” the pilot of the US jet radioed back. “I have you off my left wing and intend to proceed west. I request that you do the same, over.” The Chinese did not respond and escorted the US plane for 15 more minutes before turning away. The incident is apparently nothing special nowadays. “I would say it’s just another Friday afternoon in the South China Sea,” Marine Commander in charge Marc Hines told the CNN team. The Paracel archipelago counts 130 small coral islands and reefs spread over 15,000 square kilometers of sea area and is disputed between China, Vietnam, and Taiwan. Beijing has de facto control of the islands. ck

German chemicals group Covestro plans to build a factory for thermoplastic polyurethanes (TPU) in Zhuhai in southern China. The plant will require investments “in the low three-digit million euro range” and will be the group’s largest TPU factory when completed, it said. Covestro said the construction will take place in three phases. The first phase will be completed in 2025, and the last will be launched in 2033, it said. Then, the capacity should be 120,000 metric tons of TPU per year, it said. TPU is a plastic material used in various consumer goods, including the soles of sports shoes, cell phone housings, and parts of IT equipment or automobiles, according to Covestro.

The new site is being built in the Zhuhai Gaolan Port Economic Development Zone in Guangdong Province and will cover an area of 45,000 square meters. It will also include an innovation center. “With this new TPU facility, we aim to take advantage of the expected rapid and high market growth of the TPU market worldwide, especially in Asia and China,” the company quoted Chief Customer Officer (CCO) Sucheta Govil. ck

In 2022, the number of published patents in China’s auto sector has risen sharply. The reason for this was mainly the intensified competition in the development of technologies for EVs and connected cars, Caixin reported on Friday. According to the report, some 362,200 patents related to the automotive industry were published, 13 percent more than in 2021, the financial magazine wrote, citing data from the China Automobile IP Utilization Promotion Center (CAIPUPC). The number of patents in the electric segment increased by the same amount and accounted for the largest share of the total at 21.4 percent.

The world’s largest battery manufacturer, Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL), is particularly eager to conduct research. With 1,205 patents, it filed 268 percent more than in the previous year. This puts CATL in first place in this segment, according to Caixin. Last year, CATL still held fourth place in this ranking. Rival SVOLT is in second place with 1,049 patents. Meanwhile, South Korean giant LG has massively expanded its research activities in China, as evidenced by a sharp increase in patent applications. ck

Chinese surveillance cameras are now coming under criticism in Bulgaria as well. Bozhidar Bojanov, a member of parliament from Bulgaria’s opposition Democratic Party, has announced that he will ask the State Agency for National Security to review new surveillance cameras made by the Hikvison company on public transport in the capital Sofia. “I am saying that through Chinese and Russian technology, which are potentially compromised, strategic activity – public transport in the capital – can be negatively affected,” Radio Free Europe quoted Bojanov’s blog as saying.

According to the report, the controversy in Bulgaria centers on weaknesses in the Hikvision cameras and concerns about a lack of oversight in the procurement of the cameras, which have been in service since 2020. The transit agency responded to a Radio Free Europe inquiry that it did not have the right to impose country of origin or specific brand restrictions or requirements on equipment manufacturers in contracts. The consortium said it was guided by “needs, reliability and safety” and not by country of origin or brand.

Hikvision is the world’s largest manufacturer of video surveillance equipment. The company has come under criticism in some countries for its ties to the Chinese military and its role in developing special technology to monitor and track Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang. The US issued sanctions against the company. In the EU, there are no official restrictions on Hikvision, but the European Parliament has removed equipment manufactured by the company from its buildings. There has also been criticism over lax privacy protections and glitches discovered by researchers in Hikvision cameras upon closer inspection. ck

“All knowledge and life experience goes into translating,” says Karin Betz. Her profession: she translates Chinese literature into German. She has already made significant works by Liu Cixin, Liao Yiwu, and the Chinese literature prize winner Mo Yan accessible to the German public.

She thinks that Chinese literature has struggled in Germany so far because of the expectations of the German readership, which often thinks in pigeonholes. “Chinese literature should either be political, in the sense of being critical of the government, or esoteric, or sound as Chinese as possible,” she says. “It is not simply read as literature.”

To make matters worse, Chinese censors are holding back some exciting topics and denying funding to modern authors. “Before they become successful, authors depend on government funding. Without it, certain voices won’t be heard.”

Betz studied sinology, philosophy, and politics in Frankfurt am Main, Chengdu, and Tokyo. During her first stays in China in the early 1990s, she traveled alone by train through the country – also to remote regions, Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia. “Getting to know the great differences in this country consciously and slowly, ethnically, geographically, politically and economically, but also linguistically, was crucial for me,” she says, looking back.

After earning her master’s degree, Betz worked in various professional positions, including in Japan. Unlike work in international exchange and in business, she found university life rather confining: “In my experience, there is unfortunately still too much specialist idiocy instead of synergy,” she says – instead she preferred to go her own way. As the youngest of five siblings, she already had the necessary grit.

Betz is currently working on a translation of poetic miniatures about cats by Yu Youyou, a young poet from Sichuan. At the same time, she is working on a complex science fiction novel by Han Song.

To be successful in her work, she considers involvement with other arts to be part of the equation. For more than 20 years, Betz has been dancing Tango Argentino and DJing. “It’s part of my craft,” she explains. “It’s not just about knowledge, but also about emotion. Dance and movement are a wonderful school for empathy, intuition, and imagination.” Svenja Napp

Sam Wu will become the new head of US carmaker Ford’s China business. Wu is to move up from his current position as Managing Director and Chief Operating Officer to the role of President and Chief Executive on March 1, Ford announced. Wu succeeds Anning Chen, who will leave the company on Oct. 1.

The Nobel Sustainability Trust Foundation has honored China’s special climate envoy Xie Zhenhua as one of three recipients of its sustainability award. The foundation, led by four members of the Nobel family, cited Xie’s contribution to climate change mitigation and building global cooperation for sustainable development as the reason for the honor. Xie Zhenhua had represented China at several COP climate conferences.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

You think women belong in the kitchen? Hot pants and revealing cleavage provoke even the most prudish of men and women who wear them are therefore solely responsible for all consequences? MeToo is the devil’s work and a job for the exorcist to you? If so, you need to be strong now. Because your diagnosis is: straight man cancer, sadly it is terminal.

But let’s start from the beginning: 直男癌 zhínán’ái – “straight man cancer” – is an expression the Chinese use to describe machos and sexists. This neologism is a combination of the character for “cancer” (癌 ái, in the long form 癌症 áizhèng) and the Chinese expression for “heterosexual man” (直男 zhínán). The latter is literally taken from the English “straight man”, because 直 zhí means “straight, not curved”. The opposite in Chinese vernacular is consequently a “bent man” or “curved man”, namely the 弯男 wānnán, a “homosexual man”.

But let’s get back to the macho cancer. According to Chinese feminists (女权主义者 nǚquán zhǔyìzhě), this grows in the heads of men who can no longer be argued with and are therefore “beyond saving” (in Chinese: 没救 méi jiù). The cancer metaphor fits in perfectly with an already well-established linguistic recipe. Namely, the scolding phrase 你有病!Nǐ yǒu bìng! – “You have a disease!”. This is China’s equivalent of “You’re out of your mind” or “You’re a nutcase”. In this case, the patient is suffering from straight man cancer. Symptoms: An extremely sexist attitude coupled with exaggerated masculinity.

The mental macho tumor has a lot in common with the medical metaphor (at least in the eyes of those who use this expression). Macho cancer spreads rampantly and uncontrollably into all areas of mind and life and is a supposedly widespread disease among Y-chromosome owners. Unfortunately, curing attempts through feminist social media radiation therapy rarely yield the desired results. On the contrary, in China, they only seemed to fuel the formation of malignant masculinity metastases and the “gender war”. On the net, China’s macho men (大男子 dànánzǐ “macho, chauvinist”) verbally retaliated by coining the counterword “feminist cancer” (女权癌 nǚquán’ái), the Chinese equivalent of the English “feminazi”, a portmanteau of “feminist” and “Nazi”.

By the way, anyone who gets too involved in the debate – regardless of their chromosome type – runs the risk of becoming infected with another chronic affliction: misogyny or misandry. In Chinese internet terminology, this is also linguistically pathologized as “man-hating” or “woman-hating” syndrome (厌男症yànnánzhèng / 厌女症 yànnǚzhèng).

But while we’re at it, let’s enthusiastically beat the dust out of the cushions and look at what other male specimens could potentially take a seat on our linguistic therapy couch. In recent years, the Chinese internet vocabulary has developed a broad typology of creative expressions. The following is a selection of some highlights:

1. 普信男 pǔxìnnán – the average but over-confident man

This designation was coined by the feminist stand-up comedian Yang Li (杨笠 Yáng Lì) and has now become an established linguistic label. It refers to self-conscious men who ultimately have nothing going for them. All bark, no bite. Just as the Chinese expression says: an “average” (普 pǔ from 普通 pǔtōng “ordinary, mediocre”) but “over-confident” (信 xìn from 自信 zìxìn “self-confident”) man (男 nán).

2. 妈宝男 mābǎonán – the mama’s boy

Mum is the best, is always right, and in return pampers her offspring through and through even though he is a grown man? This description matches our mama’s boy perfectly, slightly modified in New Chinese to “mama’s sweetheart” (妈宝 mābǎo – from 妈 mā “mama” and 宝 bǎo “sweetheart”).

3. 凤凰男 fènghuángnán – the phoenix man

He has “risen from the ashes” and achieved greatness and glory in his adult life – the Phoenix Man (from 凤凰 fènghuáng “phoenix”). In China, this is the name given to men who, thanks to intelligence, hard work and a good education, worked their way up from humble to poor backgrounds and all the way to the top. Unfortunately, the memories from the past often catch up with these gentlemen, in the form of inferiority complexes. They then try to obsessively compensate for or cover up their inferiority complexes with a variety of quirks, both at work and in their personal lives. Another obvious case for the couch.

4. 软饭男 ruǎnfànnán – the man who lives off women.

This beau uses his charm to wrap wealthy ladies around his finger and to live off them. In Chinese, this is called “eating soft rice” (吃软饭 chī ruǎnfàn). So we are dealing with an opportunistic and submissive “soft rice gigolo” (软饭男 ruǎnfànnán).

5. 甘蔗男 gānzhènán – the sugar cane man

Do not fall for this sweetie! The sugarcane man pretends to be a softie – technically a “warmie” in Chinese (暖男 nuǎnnán for “softie, womanizer”). But he is actually a real “crumb man” (渣男 zhānán), an unfaithful pig. But what does that have to do with a sugar cane (甘蔗 gānzhè)? Well, those who have chewed on fresh sugar cane stalks – a popular summer street snack in China – know all about it: The first bites are sweet and juicy, only to soon leave you with crumbly, inedible fibers in your mouth that you have to spit out as soon as possible.

6. 画饼男 huàbǐngnán – the cookie artist guy

And last but not least: the biscuit artist guy. Marriage, car, apartment – this guy promises women the moon. But these are nothing but empty promises in the end, because the wannabe stud can’t keep them. In Chinese, such empty promises and unrealistic hopes are called “painting a cake” (also: drawing a sausage or flatbread – 画饼 huàbǐng). The corresponding type of man was therefore dubbed “cake painter” or “cookie artist guy” – 画饼男 huàbǐngnán – by the net community.

And which types of men roam around in your life? What you are missing now is probably a female typology guide. Of course, this could also be done for Chinese – but that is a story for another column.

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.

In China.Table number 529 last Friday, two figures in the chart on Silk Road trade were reversed. Saudi Arabia is the top recipient of investment with 30 billion US dollars, while Russia comes in second with 15 billion US dollars.