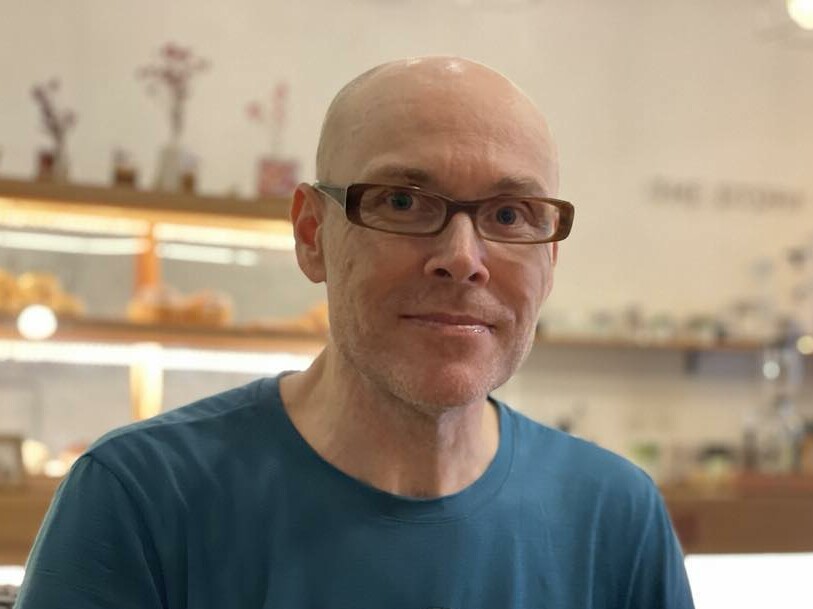

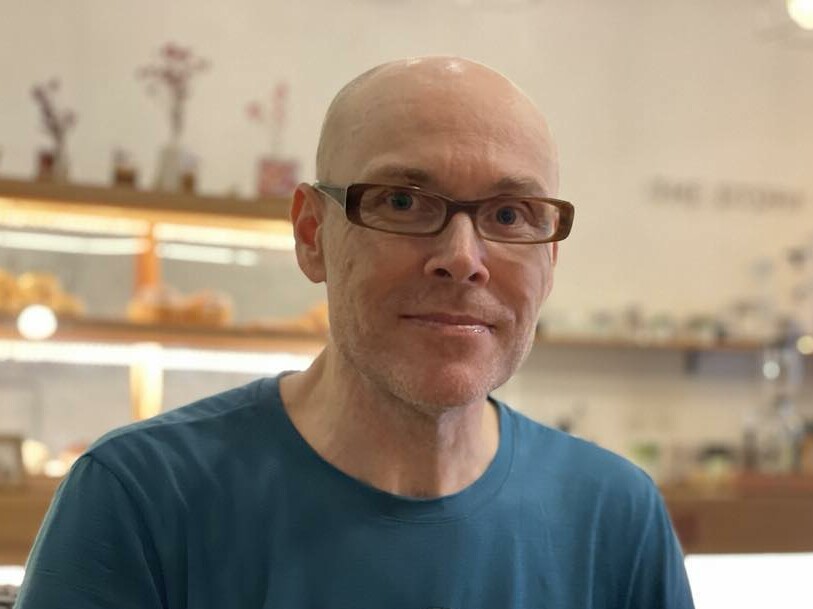

The approach to dealing with China has started changing – only slowly on the political stage in Berlin, but much more so in Brussels. EU top diplomat Gunnar Wiegand has contributed significantly to this change. For many years, he was in charge of Europe’s relations with a total of 41 countries, most recently primarily with the People’s Republic.

After more than 30 years in Brussels, the top German diplomat is now retiring. In conversation with Amelie Richter, Wiegand takes stock and urges Europe’s companies to reduce their dependence on China. Now that politicians have set the course, it’s up to the business community.

Unlike photovoltaics, Europe does not yet have any direct dependencies in the wind power sector. However, this could change quickly. Europe’s first offshore wind farm with Chinese turbines has been built in southern Italy. And these turbines are powerful: The mega-turbines made by Mingyang can already produce up to 67 million kWh of electricity per year, enough to supply 80,000 people. Even more powerful turbines are already close to market readiness.

Could a similar scenario loom as ten years ago, when the German photovoltaic industry – a leader at the time – collapsed under the onslaught of Chinese competition due to insufficient political backing? The European industry is nervous, writes Christiane Kuehl.

Mr. Wiegand, your time at the EEAS is coming to an end after a good twelve years. You have worked for the EU for over 30 years. What is your personal assessment of EU-China relations and EU-Asia relations?

In the past, issues and challenges in the vast Asia-Pacific region, as well as the opportunities there, were only recognized by experts, who acknowledged them as an important area of foreign, security and economic policy. Or by people who were trading with or investing in the region. The same goes for global challenges like climate, energy and the environment. This has changed: Europe has realized that it needs to be a global player and that very important issues are decided in the region that affect us directly and are of great significance for our global cohesion.

What did that mean specifically for your Asia department?

I am pleased that we have significantly expanded our China policy in these years. But we also have a clear India policy, relations with Japan and Korea have a new quality, we managed to establish a strategic partnership with ASEAN, and developed a strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. Europe has become far more active in all major policy areas. And our member states individually see it that way too. The best example is Germany’s recent China strategy and its National Security Strategy. Europe has matured to not only think globally, but also to position itself and act globally.

The idea that the EU considers itself a geopolitical player and would also like to establish itself as such has been firmly emphasized, especially in recent years under EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. Do you think efforts have been sufficient in this respect? What can the EU do even better?

When Jean-Claude Juncker became president, he said: “I will be President of a political European Commission.” That already raised a lot of eyebrows at the time. Then Ursula von der Leyen came and said: “I will be President of a geopolitical European Commission.” I think that precisely expresses the direction in which Europe must now position itself. We have to see things in a global context and be able to act with long-term impact.

And what’s not going so well?

One problem is that our complicated European decision-making structures and the way we reach results together are built on the will for intra-European integration, which has successfully overcome the legacy of countless European wars, civil wars and dictatorships, with the tools the founding fathers of the EU have given us. However, we must now position ourselves to act swiftly, with long-term effect and a global perspective. We need to address the challenges of multipolar competition. And the European Union, which is per definition a multilateral union, may not be able to act in this as quickly and consistently as nation states do. This will be an important challenge to consider in the coming years and hopefully lead to changes in our institutional structure and decision-making, at the latest, when the next round of enlargement takes place.

How do you look back on relations with China?

We have become more realistic in our analyses. Not only do we see the countless opportunities that our companies, including many citizens, have been able to seize with China’s rapid economic development over the past decades. The decisive change in the EU’s relationship with China occurred in 2019. Here, China was categorized as a partner, a competitor and a systemic rival. In the meantime, we have also seen that you often have to be able to differentiate accordingly also in an individual policy area. The European Council has repeatedly confirmed this triad, most recently in June this year. It is a federal element to bring all our member states together. And it is essential that we stand behind it and can identify with it, even if one member state perhaps places emphasis more in one direction and the other in another.

What was the specific impact of the division?

We were able to initiate or pass a whole series of concrete legislative projects. For example, from the International Procurement Instrument to inbound investment screening, the Due Diligence Act for Supply Chains or the Anti-Coercion Instrument. All such concrete steps position Europe better also in the competition with China in terms of reciprocity and level playing field, utilizing the capabilities of the EU’s internal market rule-making and trade policy.

However, nothing came of the CAI on the partner side.

I won’t sugar coat that this was a significant setback. The fact that China considered it necessary to respond to targeted EU sanctions against four individuals and a company in Xinjiang for human rights violations with massive, unfounded and disproportionate counter-sanctions against EU decision-makers was, of course, highly counterproductive. But with that, the last illusion of some that everything can be resolved through cooperation also vanished. I believe we have now reached a very realistic assessment.

What do you think are the defining points that will shape the future relationship with China?

Firstly, how China positions itself towards Russia. We expect much more from a permanent UN Security Council member to help end Russia’s war against Ukraine in accordance with the UN Charter. Secondly, we have Europe’s important positioning on Taiwan: to maintain the status quo and not escalate tensions. We are in a critical and very intensive exchange with the Chinese side over this: everything must be done to preserve peace and stability in this region, which is so important for Europe, for the world. And thirdly, the point that Mrs von der Leyen emphasized in her speech in March and during her visit to Beijing in April: de-risking yes and not economic decoupling, meaning the conscious reduction of one-sided, critical dependencies, and thus vulnerabilities. China holds a quasi monopoly on an increasing number of important raw materials and products. Here, companies will, of course, have to make an important contribution of diversification of their own.

Gunnar Wiegand was Head of the Asia Department at the European External Action Service (EEAS) from January 2016 to August 2023. Previously, he was Deputy Head for the Europe and Central Asia Division and Director of the Russia, Eastern Partnership, Central Asia and OSCE Division at EEAS. Prior to joining EEAS, Wiegand held various positions related to external relations and trade policy at the European Commission since 1990.

Wiegand will become Visiting Professor at the College of Europe in Bruges, Belgium, after the summer break. He will be part of the Department of EU International Relations and Diplomacy Studies.

Has anyone heard of Mingyang Smart Energy? In July, the company based in the Sichuan province announced the first commercial installation of its MySE 16-260 mega-turbine at the company’s Qingzhou 4 offshore wind farm in the South China Sea. According to Mingyang, MySE 16-260 can generate 67 million kWh of electricity annually, equivalent to the consumption of 80,000 people. In January, Mingyang also presented prototypes of the world’s largest wind turbine, with a diameter of 280 meters and an output of 18 megawatts (MW). Such giants are only suited for offshore wind farms, and that is precisely where Mingyang is now stepping up its involvement, including with European partners.

For instance, Mingyang equipped the 30-megawatt Beleolico offshore wind farm off southern Italy in 2022. Although Beleolico is small, it is Europe’s first offshore wind farm to use turbines from China. In June, Mingyang also formed a strategic partnership with the UK’s Opergy Group, primarily to drive the development of offshore wind farms in the UK. “The UK is a pivotal market for the expansion of our clean energy portfolio,” said Ma Jing, International CEO of Mingyang. Back home, Mingyang is also building a wind farm off the coast of Guangdong in partnership with BASF.

However, such partnerships have been the big exception so far. According to the industry association, WindEurope in Brussels, nearly all European wind farms use European-made turbines: “There are over 250 factories around Europe making turbines and components.” The top dogs are Vestas, Siemens Gamesa and the wind division of GE.

But they could now face competition from the Far East. Just as in photovoltaics ten years ago and more recently in heat pumps, Chinese manufacturers are also pushing into the global wind power markets. And no other country builds as many wind turbines yearly as the People’s Republic.

As the consultancy agency Trivium Netzero explains, China is deliberately marketing its renewable technology overseas. Recently, at the Central Asia Summit as well as at summit meetings with Brazil and Saudi Arabia, China has signed agreements on the construction of wind farms, among other things. For instance, Shanghai-based private company Universal Energy signed a contract to build a 500 MW wind farm in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Universal Energy is also one of the largest renewable investors in Kazakhstan, according to Trivium Netzero.

Trivium experts say that tapping into promising markets such as Uzbekistan and Brazil is helping China’s clean-tech suppliers to build further economies of scale and cost over Western competitors. And they expect such initiatives to grow even further. Beijing does not want to rely solely on EU or US sales markets.

Because the EU is a promising, but not an easy market for China’s turbine manufacturers. Brussels aims to increase the share of wind power in European electricity consumption from 17 percent today to 43 percent by 2030. According to WindEurope, this means building 30 gigawatts (GW) of new wind power capacity every year. However, both the EU and manufacturers are struggling to build the wind turbines necessary for this feat themselves as much as possible.

The problem: According to WindEurope, the European wind supply chain is already experiencing bottlenecks: “Offshore foundation manufacturers and installation vessels are fully booked for several years. The wind industry is having to buy power cables, gearboxes and even steel towers from China.” Although new factories are being built, it is not enough for the massive expansion envisaged.

The sector is nervous. Because turbine manufacturers like Mingyang are receiving their first orders from Europe thanks to these bottlenecks. And this, as WindEurope criticizes in a position paper, “not least with their cheaper turbines, looser standards and unconventional financial terms.” Therefore, the association is urging the EU for more options for non-price criteria in auctions for wind power projects. The first draft of the EU’s planned Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) aimed at strengthening supply chains for the energy transition is too weak in this regard, it says and needs to be improved. “There is a very real risk that the expansion of wind energy Europe will be made in China not in Europe.”

Some partnerships make sense because of the urgency of new projects and supply bottlenecks. The German energy company RWE has ordered 104 wind turbines from Danish company Vestas for the Nordseecluster, an offshore wind farm with a capacity of 1.6 GW, and 104 foundations from China’s Dajin Offshore. Both have been chosen as preferred suppliers, RWE said. Dajin Offshore is the largest private Chinese offshore foundation, transition piece and offshore tower manufacturer, according to RWE.

“European wind should continue to draw from China’s industrial base and engineering expertise,” writes Joseph Webster, China expert at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center, adding that Europe must also ensure it remains competitive. “Siemens Gamesa, Vestas, GE, and other Western wind turbine manufacturers are struggling to reach profitability.” A well-known problem case is Siemens Energy, which has long been in the red with its renewable energy business at its Spanish wind power subsidiary Gamesa. A few weeks ago, Siemens Energy had to acknowledge quality problems at Gamesa, including rotor blades.

So far, however, the EU does not import large quantities of completed wind turbines from China. International turbine trade is naturally limited due to the enormous size of the turbines, along with transport costs, says Webster. And unlike photovoltaics a decade ago, wind turbine manufacturers now receive political support. “Given these technical, economic, and political factors, there is a low risk that Chinese wind manufacturing firms will be able to undercut European wind turbine manufacturers in their home market,” the expert believes.

The Europeans should be cautious regarding raw materials, especially with rare earth minerals, which are also required for wind turbines. He recommends the EU diversify raw material supplies and elsewhere to continue cooperating with China, albeit with increased vigilance. The principle of de-risking also applies here.

On Sunday, China’s State Council issued guidelines aimed at improving the foreign investment environment to help attract more foreign investment.

In a document containing 24 guidelines, relevant authorities are urged to better protect the rights and interests of foreign investors, including through stronger enforcement of intellectual property rights. It also announced guidelines for more tax incentives for foreign-invested companies, such as a temporary income tax exemption for foreign investors who reinvest their profits in China. The State Council also said it would explore a “convenient and secure management mechanism” for cross-border data flows.

While the People’s Republic’s economic recovery has been slow, the country seeks foreign capital, yet many investors shy away from the risks. In addition to deteriorating political relations with many countries, Beijing’s focus on national security, in particular, makes the investment environment harder to predict. rtr

Country Garden, one of China’s largest private real estate groups, has suspended trading of some of its bonds. Over the weekend, the real estate developer announced that eleven onshore bonds will be suspended from trading indefinitely starting Monday.

The company, specializing in real estate in smaller cities, announced a loss of up to 55 billion yuan (6.9 billion euros) for the first half of the year on Thursday. Country Garden was more than 180 billion euros in debt at the end of 2022. Chinese financial newspaper Yicai previously reported that the heavily indebted real estate giant would soon begin restructuring its loans. This sent the company’s shares and dollar bonds plummeting in Hong Kong on Friday.

China’s real estate developers, which account for about a quarter of China’s economy, have been in crisis since 2021. At that time, the woes of China Evergrande and Sunac China had made headlines around the world as prices dropped and money ran out. Most recently, hope rested on the Politburo of the Communist Party, which promised swift aid for the ailing industry in late July. But so far, virtually nothing has happened.

Country Garden was long considered one of the most financially stable real estate developers. In a mandatory announcement, the group apologized for failing to recognize the extent of the crisis early on and for not taking countermeasures sooner. “The understanding of potential risks such as excessive investment proportion in third-and fourth-tier and even lower-tier cities […] were insufficient,” it said. rtr/fpe

US President Joe Biden has called China a “ticking time bomb” due to its economic challenges. “They have got some problems. That’s not good because when bad folks have problems, they do bad things,” Biden said at an event for Democratic Party donors in the state of Utah. Biden is known for using drastic formulations. In June, for instance, he had publicly called China’s leader Xi Jinping a “dictator.”

“China is in trouble,” Biden continued. He said he did not want to hurt China and wanted a rational relationship with the country. China slipped into deflation in July after consumer prices and factory prices continued to fall. Experts interpreted this as a sign of a slowing economy in the current quarter.

Biden had signed a decree Thursday night authorizing the US Treasury to prohibit or restrict certain US investments in Chinese companies across three sectors: semiconductors and microelectronics, quantum information technologies and certain artificial intelligence systems. He clearly based the decree on national security concerns – not economic ones. China’s Foreign Ministry called the decree “blatant economic coercion and technological bullying” and held out the prospect of countermeasures. The EU Commission announced that it would analyze the planned restrictions closely. rtr/ck

China has exposed a presumed spy who allegedly worked for the US intelligence agency CIA. This was reported by the Chinese state television channel CCTV. The person in question reportedly holds Chinese citizenship and worked for a military-industrial group. It was not specified whether the person was a man or a woman. The person had been offered money and immigration to the United States in exchange for sensitive military information.

The individual, named Zeng, had been sent by their company to Italy for further training, according to the report. There, they met a US embassy official. According to CCTV, Zeng was found to have signed an espionage agreement with the United States before returning to China. Zeng had also been specially trained to be able to spy in China. The report mentions “compulsory measures” had been taken, which usually means imprisonment. rtr

Chinese-Australian journalist Cheng Lei, imprisoned in China for three years on espionage charges, has spoken out about her prison conditions in a letter to the Australian public. Describing the third anniversary of her detention, she wrote that she misses the sun. “In my cell, the sunlight shines through the window, but I can stand in it for only 10 hours a year,” the letter, forwarded by Cheng Lei’s partner Nick Coyle, reads.

Cheng worked for China’s state broadcaster and was found guilty of national security violations in a closed-door trial last year. Even Australia’s ambassador to China was denied access to the trial. The sentence is still pending. On Friday, China’s Foreign Ministry stated that the case would be handled “in strict accordance with the law” and that Cheng’s rights would be fully protected.

The 48-year-old had moved to Australia with her family at the age of ten. As an adult, she returned to China to work for the international wave of broadcaster CCTV. Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese called for Cheng’s immediate release on Saturday. He said it was important that Cheng’s human rights as an Australian citizen be respected. Australia is exerting pressure at the highest levels on China to release Cheng, Albanese said, adding that the government will continue to do so at every meeting with China. flee

The Minister-President of the German state of Saxony plans to launch a training offensive to fill the 2,000 jobs the Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturer TSMC will create in Dresden. On the one hand, the skilled workers would come from the region, he said. “We also need people from outside, of course,” Michael Kretschmer told Table.Media. “We will achieve this by launching a training offensive. However, the federal government must join in here.” The skilled labor immigration law must be designed in such a way “that it also really succeeds in bringing young people here from other regions of the world within a short time.” Saxony and Dresden would “closely accompany and support” all steps of the plant construction.

When it comes to Saxony’s image, Kretschmer is optimistic. He denies the concern that the Free State’s reputation as a country with right-wing extremist problems could scare off skilled workers: “Saxony is a welcoming country that enjoys great trust in the world.” Although he did acknowledge that right-wing extremism and racism are a threat to democracy, saying that this would be true “in Saxony and all of Germany.” Most people in Saxony are “very clear about that,” Kretschmer said. “Young people interested in exciting technologies know it: this is the right place.” He said Saxony has always focused on microelectronics, investing in skilled workers and science. “That is now bearing further fruit.” ari

When Per van der Horst was 13 years old, his father took him to flea markets in their hometown of Rotterdam. “That’s how it all started,” he says today. The flea market visits increased, and with them, the treasures the teenager took back home. As a young adult, his collection of paintings and objects was already so extensive that it took up most of his apartment. He began to sell some pieces and was surprised to be able to make money from them. Today he owns two galleries, one in The Hague, the other in Taipei.

His Taiwanese wife, Judy Wu, inspired Van der Horst to bridge the gap between the Netherlands and Taiwan. “This intercultural exchange between countries attracts me,” he says. He is particularly intrigued by artists who combine Asian art history with contemporary art.

“My taste in art is quite diverse, I started with glasswork and ceramics, now you mainly find paintings, sculptures and photographs in my galleries.” Van der Horst has also been interested for some time in generative blockchain art, i.e., computer-generated art following conditions set by the artist. To this end, he is currently working with German artist Andreas Walther on a new generative NFT collection based on the I-Ging (the Book of Changes), one of the oldest classical Chinese texts. Here, too, the focus is on the cultural connection between East and West.

Several years ago, the gallery owner shifted his center of life to Taipei, where he enjoys a fairly simple life, he says. He rides his bicycle around the city, visits galleries and museums, and reads in the small cafés in his neighborhood. And when he needs a break from the city, his bike takes him up to Yangmingshan National Park, a mountainous region with picturesque peaks in northern Taiwan. “I enjoy the view up there and that peaceful tranquility.”

On his forays through vibrant Taipei, he encounters new artworks and new ideas, which he shares with his wife at home. They jointly run the gallery in Taipei. “We have a shared vision,” Van der Horst says. “We want to bring Asian art to Europe – and to inspire as many people as possible about art in general.” Svenja Napp

Niels Schumann has been Head of Ramp-up for Audi FAW NEV in Changchun since the beginning of July. He was previously Technical Project Manager for FAW-Volkswagen.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Today, I have a question for you. Do you have cherry freedom? Or at least milk tea freedom?

This question may seem completely nonsensical at first. Let me briefly explain the meaning of these strange concepts of freedom. It all started in early 2019 around the Spring Festival. At that time, China’s Internet users complained that, despite a monthly salary of more than 10,000 yuan, they were not able to buy cherries without looking at the price. The debate was sparked by an article written by a Chinese woman titled: “26岁,月薪一万,却吃不起车厘子” Èrshíliù suì yuèxīn yī wàn, què chībuqǐ chēlízi (26 years old, monthly salary 10,000 yuan and unable to afford cherries). The question then went viral as to who had enough “cherry-freedom” (车厘子自由 chēlízi zìyóu) and who did not.

The background: Around the New Year holidays, cherries are traded like precious metals in Chinese supermarkets. For plump, ruby-red premium-quality imported cherries, packed in neat gift boxes, you sometimes have to pay up to 90 yuan per pound – the equivalent of around 12 euros. By the way, if you only know cherries from Chinese lessons as 樱桃 yīngtáo, you should know that any self-respecting Chinese fruit traders prefer to label their premium-quality purple fruit, especially imported goods, with the trendy loanword 车厘子chēlízi, which is phonetically based on the English cherry. Perhaps it just sounds more like Chilean or Californian sunshine.

At the time, “Cherrygate” triggered a big online debate about the extent of freedom one’s savings actually allow. A blogger then posted a list of “fifteen degrees of financial freedom for women” (女生财务自由划分阶段 nǚshēng cáiwù zìyóu huàfēn jiēduàn), which also went viral.

On the lowest tier was latiao freedom (辣条自由 làtiáo zìyóu), alluding to a dirt-cheap but still popular fiery-hot cult snack called 辣条 làtiáo (literally “spicy sticks”), which is virtually a staple of every Chinese supermarket. The strongly spiced, crunchy flour-based sticks can be had for as little as a few yuan. The second-lowest level is milk tea freedom (奶茶自由 nǎichá zìyóu – i.e. the freedom to order anything off the menu at the milk tea stall), followed by membership freedom (会员自由 huìyuán zìyóu – for example in the supermarket or on streaming services, which are much more affordable in China than in the West, however).

Things get more expensive when it comes to delivery service freedom (外卖自由 wàimài zìyóu). In other words, the monthly budget is enough to regularly order food from a restaurant and have it delivered to your home without having a guilty conscience. Those who do not feel any financial remorse even when they pick up their daily caffeine fill at Starbucks enjoy Starbucks freedom (星巴克自由 Xīngbākè zìyóu). Other selected freedoms of higher ranks are lipstick freedom (口红自由 kǒuhóng zìyóu – constantly adding expensive styles and new shades to one’s lipstick collection) and clothing freedom (衣服自由 yīfu zìyóu – buying often and what you like, regardless of the price).

The highest ranks on the list are (in ascending order): Mobile phone freedom (手机自由 shǒujī zìyóu), travel freedom (旅行自由 lǚxíng zìyóu), handbag freedom (包包自由 bāobāo zìyóu), freedom of romantic relationships (恋爱自由 liàn’ài zìyóu – freedom to choose a partner without demands regarding bank account balance, car or property, because a woman has enough cash in her own pocket), and last but not least: the real estate freedom (买房自由 mǎifáng zìyóu – buying what you like, money plays a secondary role).

Since then, “XX-freedom” has become a common phrase in everyday language. And so native speakers like to combine various freedom neologisms depending on the context, often ironically and with a wink at their own financial situation.

Here is a small selection of other financial freedom categories you might come across on the Internet or when talking to Chinese people:

The freedom to call a didi ride (equivalent to Uber) at any time, with zero financial regret.

the freedom to rent any place you want.

The freedom to simply block (in Chinese 拉黑 lāhēi – to “blacklist” someone) unpleasant individuals (even annoying customers or potential business partners) on social networks or messaging apps, without having to worry about the negative impact of breaking off contact or offending them could have on one’s career and ultimately one’s wallet.

The freedom to send the offspring to the kindergarten of one’s choice, without having to worry about costs and travel distances or even the need to buy property in the district.

the freedom to quit one’s current, lucrative job at any time for another (significantly less lucrative) dream job or a position with prospects that pays significantly less; incidentally, the literal meaning of 跳槽 tiàocáo is “food trough hopping.”

The freedom to be treated in the best clinic when getting sick, no matter what it costs

The freedom to simply retire at a young age

Now, for those who feel that the zìyóu word field is fuelling bad vibes, financial fears or, in the worst case, inferiority complexes, let us finish with this comforting Chinese expression: 没有钱是不行的,只有钱是不够的 méiyǒu qián shì bù xíng de, zhǐ yǒu qián shì bú gòu de – loosely translated: You can’t do without money, but money alone does not buy happiness. On this note, have a carefree working week with plenty of cherry freedom!

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.

The approach to dealing with China has started changing – only slowly on the political stage in Berlin, but much more so in Brussels. EU top diplomat Gunnar Wiegand has contributed significantly to this change. For many years, he was in charge of Europe’s relations with a total of 41 countries, most recently primarily with the People’s Republic.

After more than 30 years in Brussels, the top German diplomat is now retiring. In conversation with Amelie Richter, Wiegand takes stock and urges Europe’s companies to reduce their dependence on China. Now that politicians have set the course, it’s up to the business community.

Unlike photovoltaics, Europe does not yet have any direct dependencies in the wind power sector. However, this could change quickly. Europe’s first offshore wind farm with Chinese turbines has been built in southern Italy. And these turbines are powerful: The mega-turbines made by Mingyang can already produce up to 67 million kWh of electricity per year, enough to supply 80,000 people. Even more powerful turbines are already close to market readiness.

Could a similar scenario loom as ten years ago, when the German photovoltaic industry – a leader at the time – collapsed under the onslaught of Chinese competition due to insufficient political backing? The European industry is nervous, writes Christiane Kuehl.

Mr. Wiegand, your time at the EEAS is coming to an end after a good twelve years. You have worked for the EU for over 30 years. What is your personal assessment of EU-China relations and EU-Asia relations?

In the past, issues and challenges in the vast Asia-Pacific region, as well as the opportunities there, were only recognized by experts, who acknowledged them as an important area of foreign, security and economic policy. Or by people who were trading with or investing in the region. The same goes for global challenges like climate, energy and the environment. This has changed: Europe has realized that it needs to be a global player and that very important issues are decided in the region that affect us directly and are of great significance for our global cohesion.

What did that mean specifically for your Asia department?

I am pleased that we have significantly expanded our China policy in these years. But we also have a clear India policy, relations with Japan and Korea have a new quality, we managed to establish a strategic partnership with ASEAN, and developed a strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. Europe has become far more active in all major policy areas. And our member states individually see it that way too. The best example is Germany’s recent China strategy and its National Security Strategy. Europe has matured to not only think globally, but also to position itself and act globally.

The idea that the EU considers itself a geopolitical player and would also like to establish itself as such has been firmly emphasized, especially in recent years under EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. Do you think efforts have been sufficient in this respect? What can the EU do even better?

When Jean-Claude Juncker became president, he said: “I will be President of a political European Commission.” That already raised a lot of eyebrows at the time. Then Ursula von der Leyen came and said: “I will be President of a geopolitical European Commission.” I think that precisely expresses the direction in which Europe must now position itself. We have to see things in a global context and be able to act with long-term impact.

And what’s not going so well?

One problem is that our complicated European decision-making structures and the way we reach results together are built on the will for intra-European integration, which has successfully overcome the legacy of countless European wars, civil wars and dictatorships, with the tools the founding fathers of the EU have given us. However, we must now position ourselves to act swiftly, with long-term effect and a global perspective. We need to address the challenges of multipolar competition. And the European Union, which is per definition a multilateral union, may not be able to act in this as quickly and consistently as nation states do. This will be an important challenge to consider in the coming years and hopefully lead to changes in our institutional structure and decision-making, at the latest, when the next round of enlargement takes place.

How do you look back on relations with China?

We have become more realistic in our analyses. Not only do we see the countless opportunities that our companies, including many citizens, have been able to seize with China’s rapid economic development over the past decades. The decisive change in the EU’s relationship with China occurred in 2019. Here, China was categorized as a partner, a competitor and a systemic rival. In the meantime, we have also seen that you often have to be able to differentiate accordingly also in an individual policy area. The European Council has repeatedly confirmed this triad, most recently in June this year. It is a federal element to bring all our member states together. And it is essential that we stand behind it and can identify with it, even if one member state perhaps places emphasis more in one direction and the other in another.

What was the specific impact of the division?

We were able to initiate or pass a whole series of concrete legislative projects. For example, from the International Procurement Instrument to inbound investment screening, the Due Diligence Act for Supply Chains or the Anti-Coercion Instrument. All such concrete steps position Europe better also in the competition with China in terms of reciprocity and level playing field, utilizing the capabilities of the EU’s internal market rule-making and trade policy.

However, nothing came of the CAI on the partner side.

I won’t sugar coat that this was a significant setback. The fact that China considered it necessary to respond to targeted EU sanctions against four individuals and a company in Xinjiang for human rights violations with massive, unfounded and disproportionate counter-sanctions against EU decision-makers was, of course, highly counterproductive. But with that, the last illusion of some that everything can be resolved through cooperation also vanished. I believe we have now reached a very realistic assessment.

What do you think are the defining points that will shape the future relationship with China?

Firstly, how China positions itself towards Russia. We expect much more from a permanent UN Security Council member to help end Russia’s war against Ukraine in accordance with the UN Charter. Secondly, we have Europe’s important positioning on Taiwan: to maintain the status quo and not escalate tensions. We are in a critical and very intensive exchange with the Chinese side over this: everything must be done to preserve peace and stability in this region, which is so important for Europe, for the world. And thirdly, the point that Mrs von der Leyen emphasized in her speech in March and during her visit to Beijing in April: de-risking yes and not economic decoupling, meaning the conscious reduction of one-sided, critical dependencies, and thus vulnerabilities. China holds a quasi monopoly on an increasing number of important raw materials and products. Here, companies will, of course, have to make an important contribution of diversification of their own.

Gunnar Wiegand was Head of the Asia Department at the European External Action Service (EEAS) from January 2016 to August 2023. Previously, he was Deputy Head for the Europe and Central Asia Division and Director of the Russia, Eastern Partnership, Central Asia and OSCE Division at EEAS. Prior to joining EEAS, Wiegand held various positions related to external relations and trade policy at the European Commission since 1990.

Wiegand will become Visiting Professor at the College of Europe in Bruges, Belgium, after the summer break. He will be part of the Department of EU International Relations and Diplomacy Studies.

Has anyone heard of Mingyang Smart Energy? In July, the company based in the Sichuan province announced the first commercial installation of its MySE 16-260 mega-turbine at the company’s Qingzhou 4 offshore wind farm in the South China Sea. According to Mingyang, MySE 16-260 can generate 67 million kWh of electricity annually, equivalent to the consumption of 80,000 people. In January, Mingyang also presented prototypes of the world’s largest wind turbine, with a diameter of 280 meters and an output of 18 megawatts (MW). Such giants are only suited for offshore wind farms, and that is precisely where Mingyang is now stepping up its involvement, including with European partners.

For instance, Mingyang equipped the 30-megawatt Beleolico offshore wind farm off southern Italy in 2022. Although Beleolico is small, it is Europe’s first offshore wind farm to use turbines from China. In June, Mingyang also formed a strategic partnership with the UK’s Opergy Group, primarily to drive the development of offshore wind farms in the UK. “The UK is a pivotal market for the expansion of our clean energy portfolio,” said Ma Jing, International CEO of Mingyang. Back home, Mingyang is also building a wind farm off the coast of Guangdong in partnership with BASF.

However, such partnerships have been the big exception so far. According to the industry association, WindEurope in Brussels, nearly all European wind farms use European-made turbines: “There are over 250 factories around Europe making turbines and components.” The top dogs are Vestas, Siemens Gamesa and the wind division of GE.

But they could now face competition from the Far East. Just as in photovoltaics ten years ago and more recently in heat pumps, Chinese manufacturers are also pushing into the global wind power markets. And no other country builds as many wind turbines yearly as the People’s Republic.

As the consultancy agency Trivium Netzero explains, China is deliberately marketing its renewable technology overseas. Recently, at the Central Asia Summit as well as at summit meetings with Brazil and Saudi Arabia, China has signed agreements on the construction of wind farms, among other things. For instance, Shanghai-based private company Universal Energy signed a contract to build a 500 MW wind farm in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Universal Energy is also one of the largest renewable investors in Kazakhstan, according to Trivium Netzero.

Trivium experts say that tapping into promising markets such as Uzbekistan and Brazil is helping China’s clean-tech suppliers to build further economies of scale and cost over Western competitors. And they expect such initiatives to grow even further. Beijing does not want to rely solely on EU or US sales markets.

Because the EU is a promising, but not an easy market for China’s turbine manufacturers. Brussels aims to increase the share of wind power in European electricity consumption from 17 percent today to 43 percent by 2030. According to WindEurope, this means building 30 gigawatts (GW) of new wind power capacity every year. However, both the EU and manufacturers are struggling to build the wind turbines necessary for this feat themselves as much as possible.

The problem: According to WindEurope, the European wind supply chain is already experiencing bottlenecks: “Offshore foundation manufacturers and installation vessels are fully booked for several years. The wind industry is having to buy power cables, gearboxes and even steel towers from China.” Although new factories are being built, it is not enough for the massive expansion envisaged.

The sector is nervous. Because turbine manufacturers like Mingyang are receiving their first orders from Europe thanks to these bottlenecks. And this, as WindEurope criticizes in a position paper, “not least with their cheaper turbines, looser standards and unconventional financial terms.” Therefore, the association is urging the EU for more options for non-price criteria in auctions for wind power projects. The first draft of the EU’s planned Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) aimed at strengthening supply chains for the energy transition is too weak in this regard, it says and needs to be improved. “There is a very real risk that the expansion of wind energy Europe will be made in China not in Europe.”

Some partnerships make sense because of the urgency of new projects and supply bottlenecks. The German energy company RWE has ordered 104 wind turbines from Danish company Vestas for the Nordseecluster, an offshore wind farm with a capacity of 1.6 GW, and 104 foundations from China’s Dajin Offshore. Both have been chosen as preferred suppliers, RWE said. Dajin Offshore is the largest private Chinese offshore foundation, transition piece and offshore tower manufacturer, according to RWE.

“European wind should continue to draw from China’s industrial base and engineering expertise,” writes Joseph Webster, China expert at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center, adding that Europe must also ensure it remains competitive. “Siemens Gamesa, Vestas, GE, and other Western wind turbine manufacturers are struggling to reach profitability.” A well-known problem case is Siemens Energy, which has long been in the red with its renewable energy business at its Spanish wind power subsidiary Gamesa. A few weeks ago, Siemens Energy had to acknowledge quality problems at Gamesa, including rotor blades.

So far, however, the EU does not import large quantities of completed wind turbines from China. International turbine trade is naturally limited due to the enormous size of the turbines, along with transport costs, says Webster. And unlike photovoltaics a decade ago, wind turbine manufacturers now receive political support. “Given these technical, economic, and political factors, there is a low risk that Chinese wind manufacturing firms will be able to undercut European wind turbine manufacturers in their home market,” the expert believes.

The Europeans should be cautious regarding raw materials, especially with rare earth minerals, which are also required for wind turbines. He recommends the EU diversify raw material supplies and elsewhere to continue cooperating with China, albeit with increased vigilance. The principle of de-risking also applies here.

On Sunday, China’s State Council issued guidelines aimed at improving the foreign investment environment to help attract more foreign investment.

In a document containing 24 guidelines, relevant authorities are urged to better protect the rights and interests of foreign investors, including through stronger enforcement of intellectual property rights. It also announced guidelines for more tax incentives for foreign-invested companies, such as a temporary income tax exemption for foreign investors who reinvest their profits in China. The State Council also said it would explore a “convenient and secure management mechanism” for cross-border data flows.

While the People’s Republic’s economic recovery has been slow, the country seeks foreign capital, yet many investors shy away from the risks. In addition to deteriorating political relations with many countries, Beijing’s focus on national security, in particular, makes the investment environment harder to predict. rtr

Country Garden, one of China’s largest private real estate groups, has suspended trading of some of its bonds. Over the weekend, the real estate developer announced that eleven onshore bonds will be suspended from trading indefinitely starting Monday.

The company, specializing in real estate in smaller cities, announced a loss of up to 55 billion yuan (6.9 billion euros) for the first half of the year on Thursday. Country Garden was more than 180 billion euros in debt at the end of 2022. Chinese financial newspaper Yicai previously reported that the heavily indebted real estate giant would soon begin restructuring its loans. This sent the company’s shares and dollar bonds plummeting in Hong Kong on Friday.

China’s real estate developers, which account for about a quarter of China’s economy, have been in crisis since 2021. At that time, the woes of China Evergrande and Sunac China had made headlines around the world as prices dropped and money ran out. Most recently, hope rested on the Politburo of the Communist Party, which promised swift aid for the ailing industry in late July. But so far, virtually nothing has happened.

Country Garden was long considered one of the most financially stable real estate developers. In a mandatory announcement, the group apologized for failing to recognize the extent of the crisis early on and for not taking countermeasures sooner. “The understanding of potential risks such as excessive investment proportion in third-and fourth-tier and even lower-tier cities […] were insufficient,” it said. rtr/fpe

US President Joe Biden has called China a “ticking time bomb” due to its economic challenges. “They have got some problems. That’s not good because when bad folks have problems, they do bad things,” Biden said at an event for Democratic Party donors in the state of Utah. Biden is known for using drastic formulations. In June, for instance, he had publicly called China’s leader Xi Jinping a “dictator.”

“China is in trouble,” Biden continued. He said he did not want to hurt China and wanted a rational relationship with the country. China slipped into deflation in July after consumer prices and factory prices continued to fall. Experts interpreted this as a sign of a slowing economy in the current quarter.

Biden had signed a decree Thursday night authorizing the US Treasury to prohibit or restrict certain US investments in Chinese companies across three sectors: semiconductors and microelectronics, quantum information technologies and certain artificial intelligence systems. He clearly based the decree on national security concerns – not economic ones. China’s Foreign Ministry called the decree “blatant economic coercion and technological bullying” and held out the prospect of countermeasures. The EU Commission announced that it would analyze the planned restrictions closely. rtr/ck

China has exposed a presumed spy who allegedly worked for the US intelligence agency CIA. This was reported by the Chinese state television channel CCTV. The person in question reportedly holds Chinese citizenship and worked for a military-industrial group. It was not specified whether the person was a man or a woman. The person had been offered money and immigration to the United States in exchange for sensitive military information.

The individual, named Zeng, had been sent by their company to Italy for further training, according to the report. There, they met a US embassy official. According to CCTV, Zeng was found to have signed an espionage agreement with the United States before returning to China. Zeng had also been specially trained to be able to spy in China. The report mentions “compulsory measures” had been taken, which usually means imprisonment. rtr

Chinese-Australian journalist Cheng Lei, imprisoned in China for three years on espionage charges, has spoken out about her prison conditions in a letter to the Australian public. Describing the third anniversary of her detention, she wrote that she misses the sun. “In my cell, the sunlight shines through the window, but I can stand in it for only 10 hours a year,” the letter, forwarded by Cheng Lei’s partner Nick Coyle, reads.

Cheng worked for China’s state broadcaster and was found guilty of national security violations in a closed-door trial last year. Even Australia’s ambassador to China was denied access to the trial. The sentence is still pending. On Friday, China’s Foreign Ministry stated that the case would be handled “in strict accordance with the law” and that Cheng’s rights would be fully protected.

The 48-year-old had moved to Australia with her family at the age of ten. As an adult, she returned to China to work for the international wave of broadcaster CCTV. Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese called for Cheng’s immediate release on Saturday. He said it was important that Cheng’s human rights as an Australian citizen be respected. Australia is exerting pressure at the highest levels on China to release Cheng, Albanese said, adding that the government will continue to do so at every meeting with China. flee

The Minister-President of the German state of Saxony plans to launch a training offensive to fill the 2,000 jobs the Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturer TSMC will create in Dresden. On the one hand, the skilled workers would come from the region, he said. “We also need people from outside, of course,” Michael Kretschmer told Table.Media. “We will achieve this by launching a training offensive. However, the federal government must join in here.” The skilled labor immigration law must be designed in such a way “that it also really succeeds in bringing young people here from other regions of the world within a short time.” Saxony and Dresden would “closely accompany and support” all steps of the plant construction.

When it comes to Saxony’s image, Kretschmer is optimistic. He denies the concern that the Free State’s reputation as a country with right-wing extremist problems could scare off skilled workers: “Saxony is a welcoming country that enjoys great trust in the world.” Although he did acknowledge that right-wing extremism and racism are a threat to democracy, saying that this would be true “in Saxony and all of Germany.” Most people in Saxony are “very clear about that,” Kretschmer said. “Young people interested in exciting technologies know it: this is the right place.” He said Saxony has always focused on microelectronics, investing in skilled workers and science. “That is now bearing further fruit.” ari

When Per van der Horst was 13 years old, his father took him to flea markets in their hometown of Rotterdam. “That’s how it all started,” he says today. The flea market visits increased, and with them, the treasures the teenager took back home. As a young adult, his collection of paintings and objects was already so extensive that it took up most of his apartment. He began to sell some pieces and was surprised to be able to make money from them. Today he owns two galleries, one in The Hague, the other in Taipei.

His Taiwanese wife, Judy Wu, inspired Van der Horst to bridge the gap between the Netherlands and Taiwan. “This intercultural exchange between countries attracts me,” he says. He is particularly intrigued by artists who combine Asian art history with contemporary art.

“My taste in art is quite diverse, I started with glasswork and ceramics, now you mainly find paintings, sculptures and photographs in my galleries.” Van der Horst has also been interested for some time in generative blockchain art, i.e., computer-generated art following conditions set by the artist. To this end, he is currently working with German artist Andreas Walther on a new generative NFT collection based on the I-Ging (the Book of Changes), one of the oldest classical Chinese texts. Here, too, the focus is on the cultural connection between East and West.

Several years ago, the gallery owner shifted his center of life to Taipei, where he enjoys a fairly simple life, he says. He rides his bicycle around the city, visits galleries and museums, and reads in the small cafés in his neighborhood. And when he needs a break from the city, his bike takes him up to Yangmingshan National Park, a mountainous region with picturesque peaks in northern Taiwan. “I enjoy the view up there and that peaceful tranquility.”

On his forays through vibrant Taipei, he encounters new artworks and new ideas, which he shares with his wife at home. They jointly run the gallery in Taipei. “We have a shared vision,” Van der Horst says. “We want to bring Asian art to Europe – and to inspire as many people as possible about art in general.” Svenja Napp

Niels Schumann has been Head of Ramp-up for Audi FAW NEV in Changchun since the beginning of July. He was previously Technical Project Manager for FAW-Volkswagen.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Today, I have a question for you. Do you have cherry freedom? Or at least milk tea freedom?

This question may seem completely nonsensical at first. Let me briefly explain the meaning of these strange concepts of freedom. It all started in early 2019 around the Spring Festival. At that time, China’s Internet users complained that, despite a monthly salary of more than 10,000 yuan, they were not able to buy cherries without looking at the price. The debate was sparked by an article written by a Chinese woman titled: “26岁,月薪一万,却吃不起车厘子” Èrshíliù suì yuèxīn yī wàn, què chībuqǐ chēlízi (26 years old, monthly salary 10,000 yuan and unable to afford cherries). The question then went viral as to who had enough “cherry-freedom” (车厘子自由 chēlízi zìyóu) and who did not.

The background: Around the New Year holidays, cherries are traded like precious metals in Chinese supermarkets. For plump, ruby-red premium-quality imported cherries, packed in neat gift boxes, you sometimes have to pay up to 90 yuan per pound – the equivalent of around 12 euros. By the way, if you only know cherries from Chinese lessons as 樱桃 yīngtáo, you should know that any self-respecting Chinese fruit traders prefer to label their premium-quality purple fruit, especially imported goods, with the trendy loanword 车厘子chēlízi, which is phonetically based on the English cherry. Perhaps it just sounds more like Chilean or Californian sunshine.

At the time, “Cherrygate” triggered a big online debate about the extent of freedom one’s savings actually allow. A blogger then posted a list of “fifteen degrees of financial freedom for women” (女生财务自由划分阶段 nǚshēng cáiwù zìyóu huàfēn jiēduàn), which also went viral.

On the lowest tier was latiao freedom (辣条自由 làtiáo zìyóu), alluding to a dirt-cheap but still popular fiery-hot cult snack called 辣条 làtiáo (literally “spicy sticks”), which is virtually a staple of every Chinese supermarket. The strongly spiced, crunchy flour-based sticks can be had for as little as a few yuan. The second-lowest level is milk tea freedom (奶茶自由 nǎichá zìyóu – i.e. the freedom to order anything off the menu at the milk tea stall), followed by membership freedom (会员自由 huìyuán zìyóu – for example in the supermarket or on streaming services, which are much more affordable in China than in the West, however).

Things get more expensive when it comes to delivery service freedom (外卖自由 wàimài zìyóu). In other words, the monthly budget is enough to regularly order food from a restaurant and have it delivered to your home without having a guilty conscience. Those who do not feel any financial remorse even when they pick up their daily caffeine fill at Starbucks enjoy Starbucks freedom (星巴克自由 Xīngbākè zìyóu). Other selected freedoms of higher ranks are lipstick freedom (口红自由 kǒuhóng zìyóu – constantly adding expensive styles and new shades to one’s lipstick collection) and clothing freedom (衣服自由 yīfu zìyóu – buying often and what you like, regardless of the price).

The highest ranks on the list are (in ascending order): Mobile phone freedom (手机自由 shǒujī zìyóu), travel freedom (旅行自由 lǚxíng zìyóu), handbag freedom (包包自由 bāobāo zìyóu), freedom of romantic relationships (恋爱自由 liàn’ài zìyóu – freedom to choose a partner without demands regarding bank account balance, car or property, because a woman has enough cash in her own pocket), and last but not least: the real estate freedom (买房自由 mǎifáng zìyóu – buying what you like, money plays a secondary role).

Since then, “XX-freedom” has become a common phrase in everyday language. And so native speakers like to combine various freedom neologisms depending on the context, often ironically and with a wink at their own financial situation.

Here is a small selection of other financial freedom categories you might come across on the Internet or when talking to Chinese people:

The freedom to call a didi ride (equivalent to Uber) at any time, with zero financial regret.

the freedom to rent any place you want.

The freedom to simply block (in Chinese 拉黑 lāhēi – to “blacklist” someone) unpleasant individuals (even annoying customers or potential business partners) on social networks or messaging apps, without having to worry about the negative impact of breaking off contact or offending them could have on one’s career and ultimately one’s wallet.

The freedom to send the offspring to the kindergarten of one’s choice, without having to worry about costs and travel distances or even the need to buy property in the district.

the freedom to quit one’s current, lucrative job at any time for another (significantly less lucrative) dream job or a position with prospects that pays significantly less; incidentally, the literal meaning of 跳槽 tiàocáo is “food trough hopping.”

The freedom to be treated in the best clinic when getting sick, no matter what it costs

The freedom to simply retire at a young age

Now, for those who feel that the zìyóu word field is fuelling bad vibes, financial fears or, in the worst case, inferiority complexes, let us finish with this comforting Chinese expression: 没有钱是不行的,只有钱是不够的 méiyǒu qián shì bù xíng de, zhǐ yǒu qián shì bú gòu de – loosely translated: You can’t do without money, but money alone does not buy happiness. On this note, have a carefree working week with plenty of cherry freedom!

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.