Many Western media – including the public – enjoy the narrative of a united global alliance against a cornered Putin. But even if Japan, the traditional ally of the US in Asia, joins in, the anti-Russia alliance still does not span the globe as fully as the picture suggests. Not the entire South and Southeast of Asia are on board. Above all, the ten members of ASEAN are unwilling to side with the United States, writes Frank Sieren. They consider their economic relations with China far too important.

Indeed, the statements of Southeast Asian leaders on the Ukraine crisis have tended to echo Beijing’s rhetoric. This is also remarkable because many of these countries are locking horns with China over maritime territories. The navy of the People’s Republic seizes disputed South Sea islands faster than ever before, analyzes Christiane Kuehl. And yet, Beijing gains new allies in the Pacific. The Solomon Islands have now turned their backs on Taiwan and signed a security treaty with China. All this to the displeasure of US President Joe Biden, who finds far fewer allies for his policies in Asia than he had hoped.

The lockdown in Shanghai will continue to be an important topic for us. Especially since it is the harbinger of a long series of curfews. Omicron can only be contained with severe measures. Since the zero-covid policy has become a government doctrine, it cannot be relaxed – especially since China’s healthcare system would quickly become overwhelmed by an exponential growth of infections. Meanwhile, disruptions in production have begun to show. Surveys by the Chamber of Commerce and the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics unanimously report an anxious mood among companies. Omicron in Asia and the war in Europe are blending into a vicious storm for the economy.

The Solomon Islands only have a population of around 700,000 and are located far out in the Pacific, just under 2,000 kilometers northeast of Australia. As remote as it may sound, the island nation has allowed itself to be drawn into the middle of an international conflict. It has signed a security framework agreement with China, as the government in Honiara announced on Thursday. A previously available draft envisaged, for example, that “China may, according to its own needs and with the consent of the Solomon Islands, make ship visits to, carry out logistical replenishment in, and have stopover and transition in Solomon Islands”.

The prospect of Chinese naval vessels sailing in the Pacific immediately had regional top dogs and US allies Australia and New Zealand scrambling. The agreement would risk “potential militarization of the region,” New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said on Monday. Similar comments were heard from Canberra.

The Solomon Islands and China rejected the criticism. “It is clear we need to diversify the country’s relationship with other partners. What is wrong with that?” said Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare on Tuesday. He added that there was “no intention whatsoever to ask China to build a military base in the Solomon Islands.” Nothing would change in the existing partnership with Australia. China’s foreign office spokesman Wang Wenbin said Australia’s indications were deliberately aimed at creating tension.

But this cannot hide the fact that this new partnership is a major success for Beijing. After all, until its switch to China in 2021, the Solomon Islands was one of the few countries that maintained diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

Sogavare stressed that the Solomon Islands have no intention to “pick sides”. But it is precisely this pressure that countries in the region are beginning to feel. The United States seeks alliances that more or less directly challenge China’s hegemony in the region, AUKUS, for example (US, Australia, UK), or Quad (US, Australia, Japan, India). “Keeping the region away from direct conflict with its giant neighbor the People’s Republic of China has long been considered to be imperative for economic development,” says Arrizal Jaknanihan of the Institute of International Relations at Indonesia’s Gadjah Mada University. But recent frictions with the People’s Republic in the region could soften this thinking.

Jaknanihan referred to statements made by US Admiral John C. Aquilino that circulated a few days ago. China has fully militarized at least three islands in the South China Sea, Aquilino told the Associated Press. This militarization included fighter jets, anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile systems, lasers, and jamming equipment, Aquilino stated. This would mark China’s largest military buildup since World War II. “They have advanced all their capabilities and that buildup of weaponization is destabilizing to the region.”

The South China Sea, with its numerous littoral states and overlapping territorial claims, has been a geopolitical flashpoint for years. It is a strategically important sea lane, rich in raw materials and fish shoals. China lays claim to about 90 percent of the waterway based on a historic “nine-dash line”. Since 2014, it has filled artificial islands on several atolls in the area, built harbors, residential buildings and naval bases. Beijing ignores the ruling of an international court in 2016 that declared its claims illegitimate.

Since 2020, China has also significantly increased its coast guard patrols and military maneuvers in the disputed waters. In the spring of 2021, more than 220 alleged fishing vessels anchored in phases on Whitsun Reef in the Spratly archipelago, a disputed area between China and the Philippines. The incident sparked a debate in Manila on a stronger deterrence strategy toward China.

The alleged “fishing vessels” of Whitsun Reef are much larger and stronger than typical fishing vessels of the region, according to Andrew Erickson, a professor at the China Maritime Studies Institute of the US Naval War College. Their hulls are particularly robust, and they have water cannons mounted on the mast, Erickson wrote in the US journal Foreign Policy at the time. This makes these vessels “powerful weapons in most contingencies, capable of aggressively shouldering, ramming, and spraying overmatched civilian or police opponents.”

In June 2021, the Chinese Coast Guard demonstratively patrolled near Malaysian gas drilling operations near Sarawak Province in Borneo, while Chinese fighter jets skirted the edge of Malaysian airspace. In response, Kuala Lumpur mobilized its air force and submitted a formal complaint.

In December, information surfaced that China had ordered Indonesia shortly before to stop its drilling for oil and natural gas in maritime areas near the Natuna Islands, which lie just outside China’s “nine-dash line”. Following this incident, Indonesia decided to purchase nearly 80 fighter jets from France and the United States, according to Jaknanihan. It also revived the idea of an informal alliance of willing ASEAN states against China. In early March, vessels of the Philippines Coast Guard and China nearly collided near the Scarborough shallows, which are one of the richest fishing grounds in the region.

China sees the South China Sea as its core interest, which rules out a territorial compromise. But Beijing also considers the surrounding region its sphere of influence, where the United States and others should have no business being. Head of state Xi Jinping believes in spheres of influence, says Richard McGregor, Asia-Pacific expert at Australia’s Lowy Institute. The US sphere of influence includes Latin America – and China includes Asia. “Only superpowers have complete sovereignty according to this thinking. All other countries have to adapt. And if their neighbors behave well, they will be treated well,” McGregor told China.Table.

McGregor recalls a telling moment from the 2010 ASEAN Summit in Hanoi. There, then-foreign minister and now-foreign policy czar Yang Jiechi jumped out of his skin when Singapore’s representative explained his take on the situation in the South China Sea. “Yang lost his temper and shouted, ‘We are a big country, you are a small country, and that is just a fact.’” China continues to act on that principle to this day.

The US is watching all this with growing suspicion. The Trump administration already drew up an Indo-Pacific strategy in 2017, calling for “free and open sea lanes” and against “unilateral coercive measures” – a term the US repeatedly uses to refer to China. The EU also drafted an Indo-Pacific strategy in 2021 that calls for more local maritime presence. In its recently unveiled “strategic compass”, the EU warned, among other things, that China is “increasingly both involved and engaged in regional tensions” (China.Table reported).

On February 28, the U.S. government still made a press statement stating that it was “looking forward to hosting the ASEAN leaders here in Washington, DC, for a Special Summit.” on March 28-29. The Biden administration had made ASEAN a “top priority”. Now, Washington has postponed the special ASEAN summit initially scheduled for this week to an unspecified date “this spring”.

The official reason given for the postponement were “scheduling problems”. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, the current chairman of the ten-nation Association of Southeast Asian Nations, officially backed this explanation. He declared on March 17, just ten days before the summit, that of ASEAN’s ten members, “some ASEAN leaders cannot attend the meeting on the proposed dates.” Only the prime minister of Singapore showed up in Washington.

The superpower calls and no one has the time? The real reason for the cancellation was revealed by ASEAN diplomats behind closed doors. Southeast Asian states do not want to be drawn to one side in the Ukraine crisis. There are also growing official indications that they do not intend to be taken over. Vietnam, along with other ASEAN members Brunei and Laos, had already abstained from voting on a UN resolution on the humanitarian consequences of Russian aggression on March 24. Along with India and China.

Politicians in the Muslim democracies of Indonesia and Malaysia are also reluctant to take clear positions against Putin. They sound more like China. “Why are Indonesians on social media so supportive of Russia,” TV station Al Jazeera already wonders. Indonesia is home to 270 million people. Distrust of the United States runs deep in the Muslim-majority country.

Indonesia urges that the “situation” must end, and “further calls on all parties to cease hostilities and put forward peaceful resolution through diplomacy.” No support for sanctions can be found there. Instead, the state-owned power company PT Pertamina wants to buy Russian oil. It is “an opportunity to buy from Russia at a good price,” CFO Nicke Widyawati said. “We have also discussed the payment arrangement, which may go through India.”

While Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah also supports the UN resolution, he has spoken out clearly against “unilateral sanctions”. If there are to be sanctions, “it should be done through the UN.”

Thailand’s government has declared that neutrality in the conflict is in its “national interest“. Nearly 7,000 Russians are currently stranded in Thailand. Pakistan, the young democracy and nuclear power with a population of around 200 million, also maintains neutrality: “We do not want to be part of any camp. We have paid a price for being in camps. That is why we are very carefully treading. We don’t want to compromise our neutrality,” said Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi.

By doing so, these nations are aligning themselves with India’s and China’s line, which is that all parties should end the war immediately, while sanctions serve no purpose. Measured by population size and economic power, they now form the vast majority of Asia. China is therefore not isolated. Even more clearly than China, India distances itself from the Western position. It is currently purchasing large quantities of Russian oil. In March alone, it bought four times as much as the monthly average for 2021. Washington has already warned Delhi not to be “on the wrong side of history.”

ASEAN counts 655 million people in the countries of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Laos, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. However, important countries position themselves against this Asian majority: South Korea, Japan, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand, nations each with traditionally close ties to the United States. So is the self-governing island of Taiwan, to which Beijing lays claim.

One trend is emerging: The emerging markets in Asia clearly distance themselves from Washington, while the established developed industrial nations side with the West. The upstarts tend to gain power in the process.

The cancelation of the ASEAN summit and India’s stance are a setback for Joe Biden’s Indo-Pacific strategy. The White House has repeatedly stated that Southeast Asia was a key focus of its foreign policy efforts. Biden “supports the rapid implementation of the Indo-Pacific Strategy.” This strategy was announced by Washington in February. It calls for allocating more diplomatic and security resources to the region to prevent China from further expanding its sphere of influence.

Beijing immediately countered after the failure of the ASEAN summit. Earlier on Monday, China’s Foreign Ministry announced that representatives of Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines and Myanmar will stay in China from today until Sunday. These countries are “important partners in promoting high-quality Belt and Road cooperation” writes state-run Global Times.

The Global Times goes even further, interpreting the situation as a point victory for Beijing. “To visit China while delaying the meeting with the US shows ASEAN’s willingness to talk with China rather than the US.” The fact that Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov will be in Beijing at the same time is probably no coincidence. Lavrov is also meeting in Beijing with Afghanistan’s foreign minister, as well as representatives from Iran, Pakistan and the Central Asian countries of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. All countries that oppose sanctions. After that, Lavrov continued to India, of all places.

Beijing’s ace in this power struggle is economic prosperity: The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which was launched in January 2021, created a free trade agreement heavily promoted by Beijing that unites the ASEAN countries with Japan, South Korea, China, Australia, and New Zealand into a giant free-trade bloc that together generates close to one-third of the global GDP.

RCEP is part of China’s strategy to increase regional trade, secure supply chains in China’s direct vicinity, and thus reduce dependence on the West. RCEP was originally drafted by Beijing as a response to the Pacific Free Trade Agreement (TPP), which Washington had excluded the People’s Republic from. So far, Biden has not been able to make up for the loss of trust that the termination of TPP triggered. Now, Trump’s mistakes are translated into a lack of political capital in Asia.

The Omicron variant of Sars-CoV-2 is about three times more contagious than any previous type and undermines existing immunities. These biological characteristics have a severe impact on China’s economy and policy. While Germany now largely lets the variant run its course, China tries to suppress its spread. This is generally a sound strategy to protect the population. Yet at the same time, economic concerns grow rapidly.

The main factor behind these concerns is the current lockdown in Shanghai. The metropolis located at the mouth of the Yangtze River is one of China’s most important economic centers. Its surrounding provinces are also home to numerous hotspots of large and small companies, for which Shanghai serves as hub. The city’s port is its gateway to global trade. German companies also produce on a large scale in the region.

The indefinite shutdown of such a location has significant impacts on GDP, the supply chain – and the mood. A snap survey by the German Chamber of Commerce in China made that very clear on Thursday. According to the survey, the war along with the Covid outbreak put a massive strain on logistics. For half of the companies surveyed, expected deliveries have already failed to materialize. Only 7 percent have not yet experienced any disruptions. One-third are postponing planned investments. For 46 percent of the companies, the Chinese market has become less attractive. Above all, executives lack guidance on how China’s pandemic policy will continue in the long term.

Meanwhile, the official Purchasing Managers’ Index for the Chinese industrial sector fell by 0.7 points to 49.5, and the index for the service sector fell by as much as 3.2 points to 48.4, according to the National Bureau of Statistics in Beijing on Thursday. The highly observed indicators thus fell below the important mark of 50, which means sentiment among companies is poor. They expect their business to shrink. “The economic situation in China has obviously been clouded by the current Omicron wave,” wrote Commerzbank analysts Hao Zhou and Bernd Weidensteiner.

The return of the pandemic is clearly seen as the reason for the drop in sentiment. “Recently, clustered outbreaks have occurred in many places in China,” Zhao Qinghe from the National Bureau of Statistics explained the negative trend. But the Ukraine war also plays a role: “Coupled with a significant increase in global geopolitical instability, production and operation of Chinese enterprises have been affected.”

The problem with Omicron: While the original variant and Delta could be kept in check with a close tracing of infections, the new variant slips through the net much easier. It spreads faster and more aggressively. Since zero covid is now government doctrine, local administrations will have to crack down on the virus with ever more severe measures.

Shanghai’s automotive industry has already suffered considerably. Volkswagen had to shut down production at its joint plant with SAIC. Toyota and Tesla also report stoppages, as do numerous suppliers. But it is not just production that has suffered; sales also stall when more than 70 million people are sitting at home already. The lockdowns have “an immediate effect on deliveries,” Bloomberg quotes Brian Gu, President of EV start-up Xpeng.

At the same time, the German industry remains dependent on intermediate supplies from Asia. Almost half of the companies surveyed are reliant on components from China, as the Munich-based Ifo Institute revealed in a recent survey. At the same time, it shows that the private sector is actively pushing for decoupling. Of the particularly dependent companies, half plan to reduce their imports from China in the future.

Unlike in 2021, this year could also see stagnation in the other direction. Not only imports from China, but also sales in China are at risk when its economic engine sputters. Aside from Corona, higher raw material prices could also weigh on the bottom line. “Cost pressure for the manufacturing sector is rising significantly again,” Commerzbank experts noted. This increases the risk of stagnation of the Chinese economy.

Omicron is thus currently a political and economic problem in China, while it is a medical problem in Germany. China is rightly trying to prevent it from becoming a medical problem in the first place. The question is whether that is possible at all. Normalization only occurs when there is a high level of immunity among the population, which presumably requires several infections for each individual on top of proper vaccination. However, China is currently not pursuing this path of massively increasing immunity that vaccination with mRNA vaccines would provide.

Chinese consumers continue to feel the economic impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine at the gas pumps: Thanks to rising global oil prices in the wake of the war, gasoline and diesel cost more in the People’s Republic than they have since at least 2006. As of Friday, price hikes of 110 yuan per ton of both fuels will again apply, according to the National Development and Reform Commission. Authorities had already raised prices several times since the Ukraine war began. The rise in crude oil has prompted China’s independent refiners to cut production. China’s three largest oil companies-China National Petroleum Corporation, China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation, and China National Offshore Oil Corporation have reportedly been asked to maintain oil production and facilitate shipments to ensure a stable supply. ari

The political shuffling within the Chinese Communist Party continues: Ying Yong, Party Secretary in the province of Hubei province, has resigned from his post “for reasons of age,” state officials announced. Ying, a Xi Jinping loyalist, turns 65 this year, reaching the usual retirement age for provincial officials. His resignation came as a surprise to many, as he had long been considered a potential candidate for higher positions. Ying, former mayor of Shanghai, had been appointed Party chief of Hubei at the height of the Covid outbreak. The virus first appeared in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei. He will now be succeeded by Wang Menghui, who was previously China’s minister of housing and urban-rural development.

There are also changes in two other provinces. Xin Changxing is the new Party chief of Qinghai. Liang Yanshun took the position of Chun Runer as the highest Party official in the Autonomous Region of Ningxia.

Before the National People’s Congress begins in autumn, the changes within China’s Communist Party are being closely watched. Since the start of the lockdown in the megacity of Shanghai, eyes are also on Li Qiang, Secretary of the Shanghai Communist Party. Li is considered a close ally of President Xi. He was considered a hot contender for a post on the Politburo Standing Committee. But the deteriorating Covid situation in the economic hub may have now cost Li a promotion. ari

“Study history!” China’s sole-ruling Party leader Xi Jinping has repeatedly urged his compatriots since he took office at the end of 2012. As early as March 2013, he urged, “Take history as a mirror” (以史为镜): “Learn from the historical experience of our party and country (来龙去脉).” That is particularly important “for creating the future, because history is the best textbook.” (历史是最好的教科书).

Beijing is not concerned with the noble goal of educating China’s population in matters of historical truth. On the contrary, Xi openly admits that he wants to reinterpret the history of his Party and the development of the People’s Republic, as well as revise textbooks and curriculum in schools and universities accordingly. The Party demonstrated what this looks like in honor of its 100th anniversary in 2021. Xi downplayed the former persecution campaigns under Mao as an unsuccessful attempt to find new ways. He even relativized Mao’s destructive Cultural Revolution or erased crimes committed by the Party leadership, such as its Tianan’men massacre in 1989, from public memory. Those who insist on depicting history as it actually happened are complicit of “historical nihilism”. Legally, this is a criminal offense.

Last year, Beijing was no longer content with merely retelling history. He wanted to change it, Xi promised in a January speech to the Party School: “Time and momentum are on our side” (时与势在我们一边). Under this guiding principle, he mocked the “end of history” proclaimed by political scientist Francis Fukuyama in 1989 after the collapse of the Soviet bloc. Time had put a true “end” to rash judgment. China, on the other hand, is entering a “new era” and will write the history of the future.

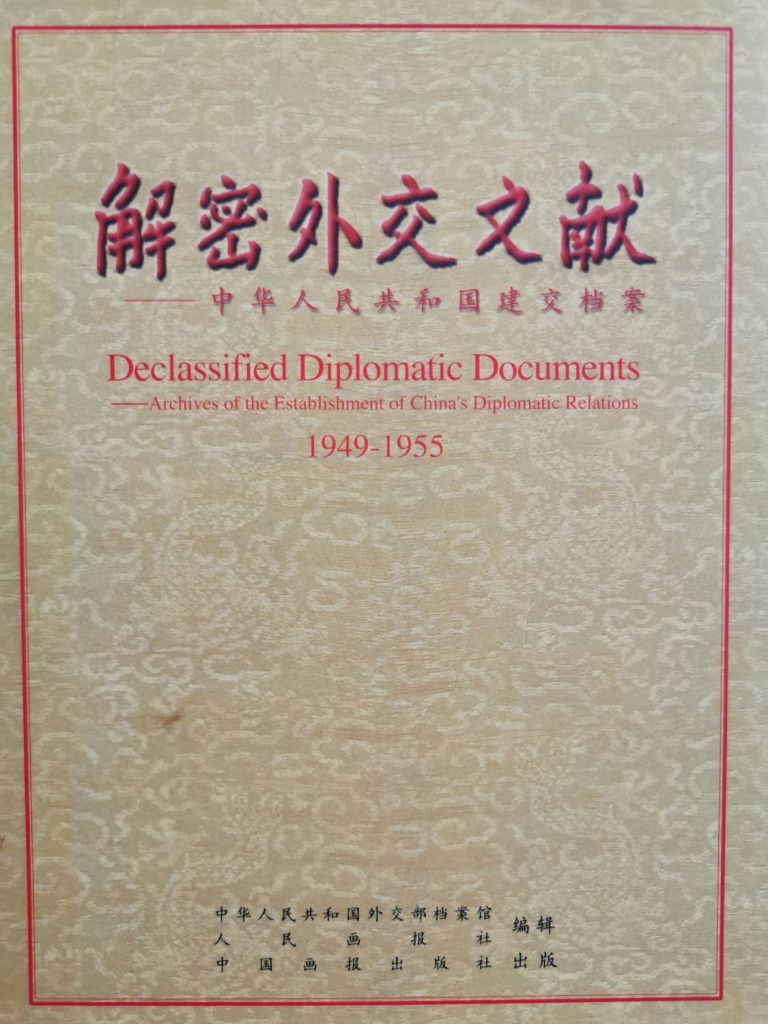

Yet China’s leadership had once tried to jump over its shadow. In 2006, a diplomat friend handed me an illustrated 670-page volume of selected historical documents published by the Beijing Foreign Ministry Archives. The gold-colored cover read, “Declassified Diplomatic Documents 1949-1955.” He praised it to me as a sign of “more openness and transparency of our history.”

The background: Beijing authorized a review of the development of the People’s Republic with the help of original historical sources. Provinces and the foreign ministry were allowed to open their archives for this purpose. In 2004, China’s Foreign Ministry for the first time released thousands of internal documents on events dating back decades for, free for the public to see. In 2006, it unsealed another 25,651 files covering the period 1956 to 1960. Renowned historian Shen Zhihua, a conflict researcher on Chinese Cold War history at Shanghai University, praised the opening of the archives as a “flower in the garden of Chinese reform.”

Even though the archive published only a third of its records and kept official documents on foreign policy decision-making under lock and key, Shen found pieces that shed new light on Beijing’s behavior during the Korean War (1950 to 1953) and explained why Mao – as the victor of the civil war – was unable to annex Taiwan in 1950. They also shed light on Beijing’s once rocky relationship with its “big brother,” the Soviet Union, which led to the sudden withdrawal of all Soviet experts from the People’s Republic in 1960. The subject has again regained relevance, as China and Russia celebrate their supposedly best friendship and cooperation of all time.

This much transparency made waves internationally. Christian F. Ostermann, Director of the Woodrow Wilson International Center in Washington, called it an “archival thaw in China”. His special documentation on the “Cold War in China,” published in 2007, was the first to analyze China’s documents in addition to the sources from the archives in Moscow and Eastern Europe, which have been open since 1992.

The thaw lasted only a few years. Beijing did not release another volume of declassified documents. Researcher Kazushi Minami of Japan’s Osaka University writes: “But as Xi Jinping came to power, the Chinese government abruptly closed the FMA in 2012.” It has been opened only sporadically ever since. 90 percent of its once-accessible documents were again locked away.

When Minami visited the archive in July 2017, he was almost alone there. He felt that “researchers are unwelcome. I felt I was under constant supervision.” The 19th Party Congress in 2017, where Xi asserted his absolute rule over the Party and the country, had cast its shadow. “China seems determined to rewrite the past. It all starts with the archives. It’s unlikely that the Xi government will loosen its control over valuable historical sources anytime soon.”

International scholars owe new insights into what once happened in China not only to open archives. They were able to, like Frank Dikoetter, who researches Mao’s campaigns, use memoirs of historical witnesses that emerged en masse in the pre-Xi era, writes Wilson Center historian Charles Kraus. Discoveries also can be made in China’s still-unregulated secondhand book and collector markets, where old diaries, private dossiers and vintage photographs are still on sale today.

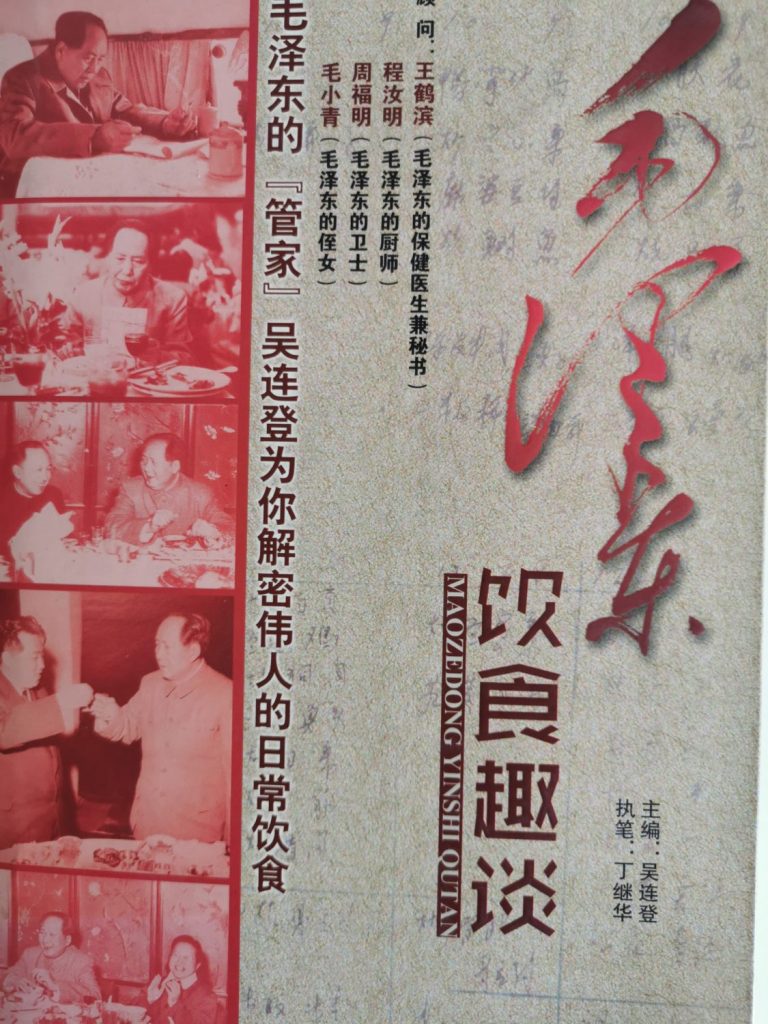

Some memoirs hide revelations, as in the 2012 chatter of Wu Liandeng, the functionary who managed the Great Chairman’s household until Mao’s death, published by the Beijing Central Committee Documents Publishing House. His anecdotes show how the dictator often revealed much about his moods and true view of things over meals, including his resentment of Soviet leaders.

In July 1962, when Mao was served a curry goulash with beef, he took it as an opportunity to mock the Soviet CP leader. The latter had elevated “goulash communism” to a social ideal, where every Soviet citizen would be served potatoes with beef once a day in the future. Laughing, Mao feasted on the curry: “Let’s eat Khrushchev now.” While doing so, he insulted Moscow’s leader, who had withdrawn all Soviet experts from China. “They want to strangle us with this. I don’t think the world will stop spinning if China breaks with the Soviet Union.” The cynicism the dictator displays in this dinner scene is boundless. A year earlier, millions of farmers had starved to death thanks to his utopian Great Leap Forward.

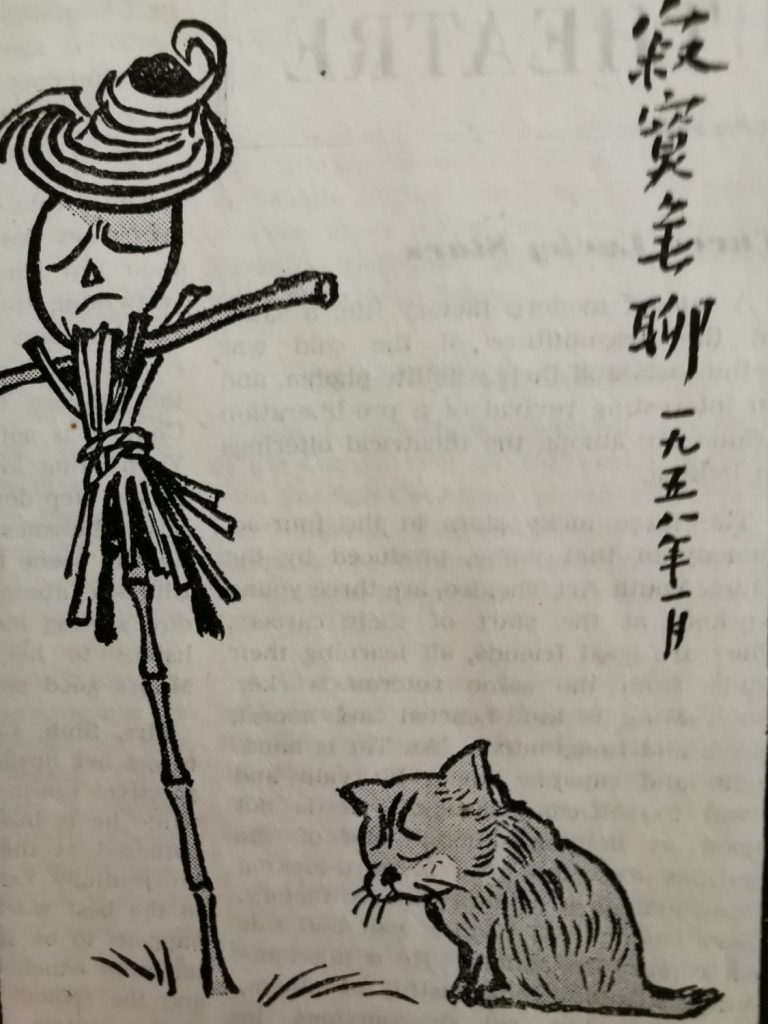

In another scene, officials wanted to offer freshly caught sparrows as a roasted delicacy to Mao, who had visited Wuhan in the summer of 1958. Mao was irritated and asked how this was possible. After all, he had been assured that the feathered “evildoers” had been completely exterminated on his orders. “These few are the only ones left,” his hosts express themselves, frightened. But Mao was in a good mood: “Then let’s exterminate them together for good.”

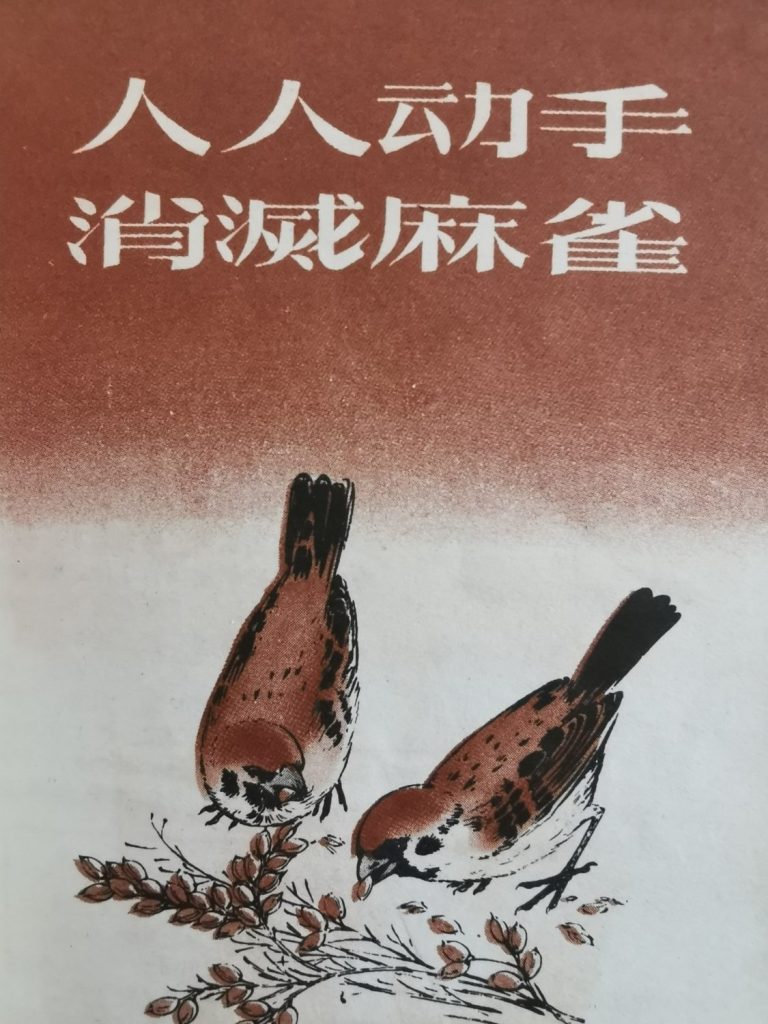

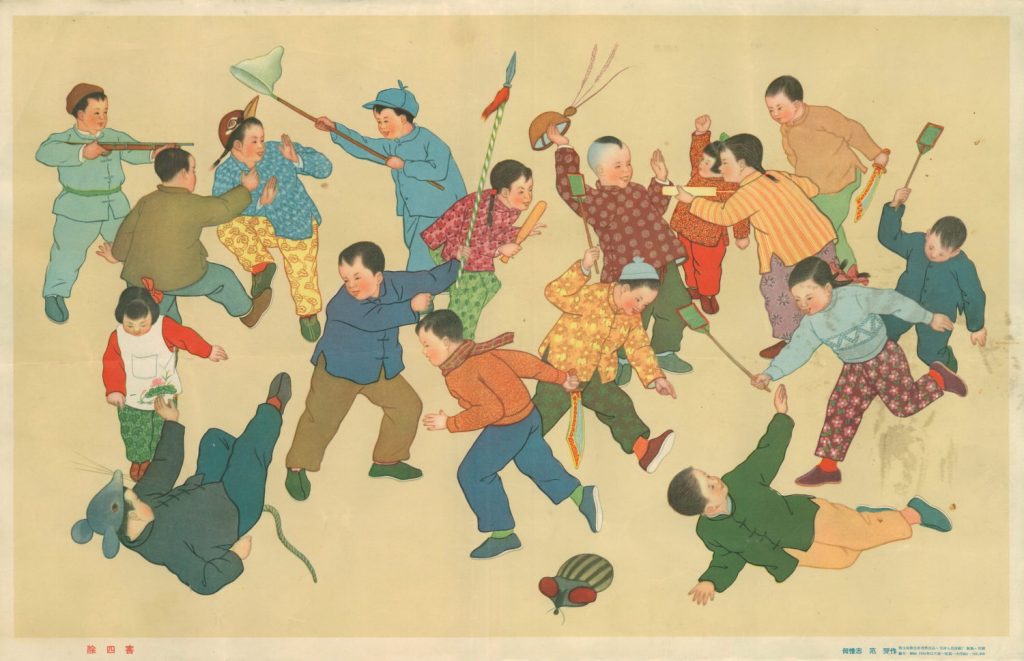

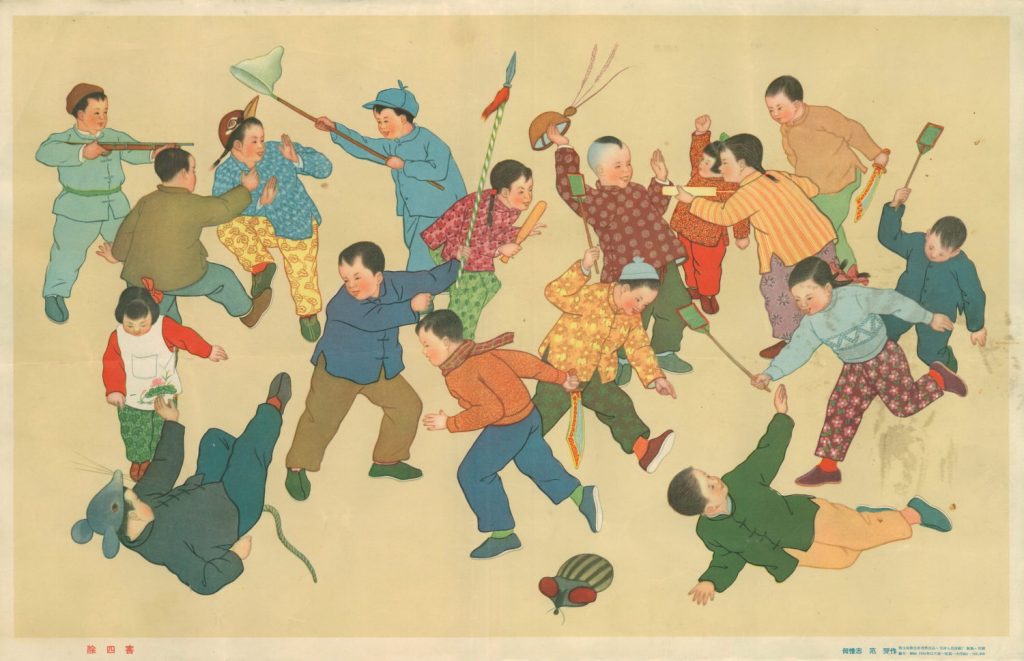

Two years earlier, one of the most absurd mass campaigns had raged through China. Mao had ordered the “eradication of the Four Evils,” the quartet of pests which included the rat, mosquito, fly, and the sparrow. The dictator had heard that a sparrow would steal up to four pounds of grain per year. To prevent a threat to China’s food supply, he mobilized six hundred million Chinese to exterminate what was then estimated to be four billion sparrows.

In September 1957, Mao put the issue on the agenda of his eighth party congress and demanded: “China must become a country in which there is no longer a single one of the four pests.” Nationwide and collectively, a hunt was called. Its peak was in 1958, when authorities across China recorded the deaths of 2.11 billion sparrows. Mao only called the hunt off when he learned from researchers at the Academy of Sciences that sparrows were primarily killing plant pests and when he read reports from his agricultural officials how his campaign was further damaging the forestry industry in the midst of an agrarian crisis. They were removed from the list of four pests and replaced by cockroaches.

According to Xi, the end of history today applies only to the declining United States and the West, but not to the rising People’s Republic, which has the future in its hands. Beijing glorifies its past and does not want to see any documents from its archives that say otherwise, nor does it want to be reminded of its insane campaigns against the sparrows. It also does not want to know what Russian researchers like Alexander Pantsov claim to have found in the Moscow archives. To speed up the recovery of the almost completely decimated sparrow population, Beijing secretly had more than a million Siberian sparrows imported from the arch-enemy Soviet Union in the early 1960s.

It took the Beijing court three hours on Thursday to discuss the case of Cheng Lei with the defendant in person. Three hours were enough for the Chinese judiciary to make a final assessment of the serious charge of leaking government secrets. This tiny short period contrasts with the long uncertainty in which the mother of two had previously been held. After all, the Chinese court had taken a long time before putting her on trial on Thursday.

The Australian woman with Chinese roots was detained 19 months ago. For almost half a year, her whereabouts were unknown. Neither did anyone know why she had been arrested in the first place. This was legal under Chinese law: police can place suspects under RSDL (Residential Surveillance in a Designated Location) for up to six months. During this time, they do not have to provide her with a lawyer or inform anyone about her whereabouts.

It was not until August 2020 that Chinese authorities informed their Australian colleagues that Cheng Lei had been formally arrested and accused of leaking secrets. The case made waves. Not only in the international community in Beijing, where the single mother readily offered private advice on which preschools were best for foreign families, but also in many parts of China, Australia and much of the political West.

Cheng had worked for China’s state broadcaster CGTN for eight years. She was known to the public as a news anchor. She never made a secret of the fact that she valued the liberal spirit of democratic systems. She once appeared as a “global alumni” in a promotional video for Australia as a university destination, aimed at young Chinese. Australia’s education system “doesn’t teach you to just follow instructions, it allows you the freedom to make up your own mind,” she said in the video.

She continued to express her own thoughts during her time at CGTN. As an Australian citizen who had emigrated from China to Down Under with her parents when she was nine years old, she did not miss any opportunity to criticize President Xi Jinping or the Chinese government’s early Covid policy on the Internet. It is not certain whether these statements had anything to do with her later arrest.

Although Chinese state media strictly adhere to public announcements by the government in their reporting, information leaked out via social media. About a year ago, a WeChat user named “Beijing small sweet melon” took up the case, revealing astonishing details about Cheng Lei’s private life and the allegations against her.

Above the post it said, “Betraying her motherland, how did CCTV famous anchor Cheng Lei become an Australian spy?” And further down, the post reads, “China has given you everything, yet you counterattack as a tool of the enemy.” More posts on social media from other accounts with pseudonyms about the case followed shortly after, all with the same tenor. Later, a video surfaced, “Spy CCTV anchor Cheng Lei: For 20 years she hid in state television, stole state secrets, now after being detained, shamelessly claims injustice.”

It is highly unlikely that such posts appear randomly on such high-profile state matters in a tightly controlled surveillance state. “These posts are written by Ministry of State Security (MSS) people to set the public tone,” Feng Chongyi of the University of Technology Sydney told Australia’s ABC radio. Feng had been detained himself for a week during a visit to China four years ago.

After Cheng Lei’s formal arrest, Australian diplomats were allowed to communicate with her once a month via video phone calls. The topics, however, were chosen by the Chinese authorities. Australia’s Ambassador Graham Fletcher was even denied entry to the courtroom on Thursday. The Australian government had asked for a minimum rule of law in the run-up to the trial.

The biggest victims of the case, however, are probably the two twelve- and ten-year-old children of the 46-year-old. The mother had brought her daughter and son to their grandmother’s home in Melbourne shortly before she disappeared. Due to the Covid outbreak in China, Cheng Lei had decided on short notice to take the two out of the country. They have not seen their mother for more than a year and a half.

In the worst case, this situation could continue indefinitely if the judges hand down a life sentence. This is possible, but not likely. The usual sentences for such charges are five to ten years in prison. A possible conviction and sentence will be announced by the Chinese court at a later date. Usually, they are in less of a hurry than during the trial itself. Marcel Grzanna

Inga Heiland will take over the management of a research center for trade-related topics at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy on April 1, 2022. In this position, Heiland will conduct research on global container shipping and global supply chains, among other topics.

Dennis Kraemer joined Daimler Greater China in Zhenjiang earlier this month as Battery Cell Launch Specialist. Kraemer was previously Outbound Logistics Specialist in Aguascalientes, Mexico, also for Mercedes-Benz.

Tobias Beck has moved from Beijing to Shanghai for the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. He also works there as a Project Manager and Research Fellow.

These tiny dots in the steppe are chirus. In fact, there are 10,000 of them. When so many of the goat-like animals gather as they do here in Gêrzê County in the western part of the Autonomous Region of Tibet, it’s good news. These animals have become rare. At present, their numbers are slowly increasing again. Chirus are also called orongos or Tibetan antelopes.

Many Western media – including the public – enjoy the narrative of a united global alliance against a cornered Putin. But even if Japan, the traditional ally of the US in Asia, joins in, the anti-Russia alliance still does not span the globe as fully as the picture suggests. Not the entire South and Southeast of Asia are on board. Above all, the ten members of ASEAN are unwilling to side with the United States, writes Frank Sieren. They consider their economic relations with China far too important.

Indeed, the statements of Southeast Asian leaders on the Ukraine crisis have tended to echo Beijing’s rhetoric. This is also remarkable because many of these countries are locking horns with China over maritime territories. The navy of the People’s Republic seizes disputed South Sea islands faster than ever before, analyzes Christiane Kuehl. And yet, Beijing gains new allies in the Pacific. The Solomon Islands have now turned their backs on Taiwan and signed a security treaty with China. All this to the displeasure of US President Joe Biden, who finds far fewer allies for his policies in Asia than he had hoped.

The lockdown in Shanghai will continue to be an important topic for us. Especially since it is the harbinger of a long series of curfews. Omicron can only be contained with severe measures. Since the zero-covid policy has become a government doctrine, it cannot be relaxed – especially since China’s healthcare system would quickly become overwhelmed by an exponential growth of infections. Meanwhile, disruptions in production have begun to show. Surveys by the Chamber of Commerce and the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics unanimously report an anxious mood among companies. Omicron in Asia and the war in Europe are blending into a vicious storm for the economy.

The Solomon Islands only have a population of around 700,000 and are located far out in the Pacific, just under 2,000 kilometers northeast of Australia. As remote as it may sound, the island nation has allowed itself to be drawn into the middle of an international conflict. It has signed a security framework agreement with China, as the government in Honiara announced on Thursday. A previously available draft envisaged, for example, that “China may, according to its own needs and with the consent of the Solomon Islands, make ship visits to, carry out logistical replenishment in, and have stopover and transition in Solomon Islands”.

The prospect of Chinese naval vessels sailing in the Pacific immediately had regional top dogs and US allies Australia and New Zealand scrambling. The agreement would risk “potential militarization of the region,” New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said on Monday. Similar comments were heard from Canberra.

The Solomon Islands and China rejected the criticism. “It is clear we need to diversify the country’s relationship with other partners. What is wrong with that?” said Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare on Tuesday. He added that there was “no intention whatsoever to ask China to build a military base in the Solomon Islands.” Nothing would change in the existing partnership with Australia. China’s foreign office spokesman Wang Wenbin said Australia’s indications were deliberately aimed at creating tension.

But this cannot hide the fact that this new partnership is a major success for Beijing. After all, until its switch to China in 2021, the Solomon Islands was one of the few countries that maintained diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

Sogavare stressed that the Solomon Islands have no intention to “pick sides”. But it is precisely this pressure that countries in the region are beginning to feel. The United States seeks alliances that more or less directly challenge China’s hegemony in the region, AUKUS, for example (US, Australia, UK), or Quad (US, Australia, Japan, India). “Keeping the region away from direct conflict with its giant neighbor the People’s Republic of China has long been considered to be imperative for economic development,” says Arrizal Jaknanihan of the Institute of International Relations at Indonesia’s Gadjah Mada University. But recent frictions with the People’s Republic in the region could soften this thinking.

Jaknanihan referred to statements made by US Admiral John C. Aquilino that circulated a few days ago. China has fully militarized at least three islands in the South China Sea, Aquilino told the Associated Press. This militarization included fighter jets, anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile systems, lasers, and jamming equipment, Aquilino stated. This would mark China’s largest military buildup since World War II. “They have advanced all their capabilities and that buildup of weaponization is destabilizing to the region.”

The South China Sea, with its numerous littoral states and overlapping territorial claims, has been a geopolitical flashpoint for years. It is a strategically important sea lane, rich in raw materials and fish shoals. China lays claim to about 90 percent of the waterway based on a historic “nine-dash line”. Since 2014, it has filled artificial islands on several atolls in the area, built harbors, residential buildings and naval bases. Beijing ignores the ruling of an international court in 2016 that declared its claims illegitimate.

Since 2020, China has also significantly increased its coast guard patrols and military maneuvers in the disputed waters. In the spring of 2021, more than 220 alleged fishing vessels anchored in phases on Whitsun Reef in the Spratly archipelago, a disputed area between China and the Philippines. The incident sparked a debate in Manila on a stronger deterrence strategy toward China.

The alleged “fishing vessels” of Whitsun Reef are much larger and stronger than typical fishing vessels of the region, according to Andrew Erickson, a professor at the China Maritime Studies Institute of the US Naval War College. Their hulls are particularly robust, and they have water cannons mounted on the mast, Erickson wrote in the US journal Foreign Policy at the time. This makes these vessels “powerful weapons in most contingencies, capable of aggressively shouldering, ramming, and spraying overmatched civilian or police opponents.”

In June 2021, the Chinese Coast Guard demonstratively patrolled near Malaysian gas drilling operations near Sarawak Province in Borneo, while Chinese fighter jets skirted the edge of Malaysian airspace. In response, Kuala Lumpur mobilized its air force and submitted a formal complaint.

In December, information surfaced that China had ordered Indonesia shortly before to stop its drilling for oil and natural gas in maritime areas near the Natuna Islands, which lie just outside China’s “nine-dash line”. Following this incident, Indonesia decided to purchase nearly 80 fighter jets from France and the United States, according to Jaknanihan. It also revived the idea of an informal alliance of willing ASEAN states against China. In early March, vessels of the Philippines Coast Guard and China nearly collided near the Scarborough shallows, which are one of the richest fishing grounds in the region.

China sees the South China Sea as its core interest, which rules out a territorial compromise. But Beijing also considers the surrounding region its sphere of influence, where the United States and others should have no business being. Head of state Xi Jinping believes in spheres of influence, says Richard McGregor, Asia-Pacific expert at Australia’s Lowy Institute. The US sphere of influence includes Latin America – and China includes Asia. “Only superpowers have complete sovereignty according to this thinking. All other countries have to adapt. And if their neighbors behave well, they will be treated well,” McGregor told China.Table.

McGregor recalls a telling moment from the 2010 ASEAN Summit in Hanoi. There, then-foreign minister and now-foreign policy czar Yang Jiechi jumped out of his skin when Singapore’s representative explained his take on the situation in the South China Sea. “Yang lost his temper and shouted, ‘We are a big country, you are a small country, and that is just a fact.’” China continues to act on that principle to this day.

The US is watching all this with growing suspicion. The Trump administration already drew up an Indo-Pacific strategy in 2017, calling for “free and open sea lanes” and against “unilateral coercive measures” – a term the US repeatedly uses to refer to China. The EU also drafted an Indo-Pacific strategy in 2021 that calls for more local maritime presence. In its recently unveiled “strategic compass”, the EU warned, among other things, that China is “increasingly both involved and engaged in regional tensions” (China.Table reported).

On February 28, the U.S. government still made a press statement stating that it was “looking forward to hosting the ASEAN leaders here in Washington, DC, for a Special Summit.” on March 28-29. The Biden administration had made ASEAN a “top priority”. Now, Washington has postponed the special ASEAN summit initially scheduled for this week to an unspecified date “this spring”.

The official reason given for the postponement were “scheduling problems”. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, the current chairman of the ten-nation Association of Southeast Asian Nations, officially backed this explanation. He declared on March 17, just ten days before the summit, that of ASEAN’s ten members, “some ASEAN leaders cannot attend the meeting on the proposed dates.” Only the prime minister of Singapore showed up in Washington.

The superpower calls and no one has the time? The real reason for the cancellation was revealed by ASEAN diplomats behind closed doors. Southeast Asian states do not want to be drawn to one side in the Ukraine crisis. There are also growing official indications that they do not intend to be taken over. Vietnam, along with other ASEAN members Brunei and Laos, had already abstained from voting on a UN resolution on the humanitarian consequences of Russian aggression on March 24. Along with India and China.

Politicians in the Muslim democracies of Indonesia and Malaysia are also reluctant to take clear positions against Putin. They sound more like China. “Why are Indonesians on social media so supportive of Russia,” TV station Al Jazeera already wonders. Indonesia is home to 270 million people. Distrust of the United States runs deep in the Muslim-majority country.

Indonesia urges that the “situation” must end, and “further calls on all parties to cease hostilities and put forward peaceful resolution through diplomacy.” No support for sanctions can be found there. Instead, the state-owned power company PT Pertamina wants to buy Russian oil. It is “an opportunity to buy from Russia at a good price,” CFO Nicke Widyawati said. “We have also discussed the payment arrangement, which may go through India.”

While Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah also supports the UN resolution, he has spoken out clearly against “unilateral sanctions”. If there are to be sanctions, “it should be done through the UN.”

Thailand’s government has declared that neutrality in the conflict is in its “national interest“. Nearly 7,000 Russians are currently stranded in Thailand. Pakistan, the young democracy and nuclear power with a population of around 200 million, also maintains neutrality: “We do not want to be part of any camp. We have paid a price for being in camps. That is why we are very carefully treading. We don’t want to compromise our neutrality,” said Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi.

By doing so, these nations are aligning themselves with India’s and China’s line, which is that all parties should end the war immediately, while sanctions serve no purpose. Measured by population size and economic power, they now form the vast majority of Asia. China is therefore not isolated. Even more clearly than China, India distances itself from the Western position. It is currently purchasing large quantities of Russian oil. In March alone, it bought four times as much as the monthly average for 2021. Washington has already warned Delhi not to be “on the wrong side of history.”

ASEAN counts 655 million people in the countries of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Laos, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. However, important countries position themselves against this Asian majority: South Korea, Japan, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand, nations each with traditionally close ties to the United States. So is the self-governing island of Taiwan, to which Beijing lays claim.

One trend is emerging: The emerging markets in Asia clearly distance themselves from Washington, while the established developed industrial nations side with the West. The upstarts tend to gain power in the process.

The cancelation of the ASEAN summit and India’s stance are a setback for Joe Biden’s Indo-Pacific strategy. The White House has repeatedly stated that Southeast Asia was a key focus of its foreign policy efforts. Biden “supports the rapid implementation of the Indo-Pacific Strategy.” This strategy was announced by Washington in February. It calls for allocating more diplomatic and security resources to the region to prevent China from further expanding its sphere of influence.

Beijing immediately countered after the failure of the ASEAN summit. Earlier on Monday, China’s Foreign Ministry announced that representatives of Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines and Myanmar will stay in China from today until Sunday. These countries are “important partners in promoting high-quality Belt and Road cooperation” writes state-run Global Times.

The Global Times goes even further, interpreting the situation as a point victory for Beijing. “To visit China while delaying the meeting with the US shows ASEAN’s willingness to talk with China rather than the US.” The fact that Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov will be in Beijing at the same time is probably no coincidence. Lavrov is also meeting in Beijing with Afghanistan’s foreign minister, as well as representatives from Iran, Pakistan and the Central Asian countries of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. All countries that oppose sanctions. After that, Lavrov continued to India, of all places.

Beijing’s ace in this power struggle is economic prosperity: The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which was launched in January 2021, created a free trade agreement heavily promoted by Beijing that unites the ASEAN countries with Japan, South Korea, China, Australia, and New Zealand into a giant free-trade bloc that together generates close to one-third of the global GDP.

RCEP is part of China’s strategy to increase regional trade, secure supply chains in China’s direct vicinity, and thus reduce dependence on the West. RCEP was originally drafted by Beijing as a response to the Pacific Free Trade Agreement (TPP), which Washington had excluded the People’s Republic from. So far, Biden has not been able to make up for the loss of trust that the termination of TPP triggered. Now, Trump’s mistakes are translated into a lack of political capital in Asia.

The Omicron variant of Sars-CoV-2 is about three times more contagious than any previous type and undermines existing immunities. These biological characteristics have a severe impact on China’s economy and policy. While Germany now largely lets the variant run its course, China tries to suppress its spread. This is generally a sound strategy to protect the population. Yet at the same time, economic concerns grow rapidly.

The main factor behind these concerns is the current lockdown in Shanghai. The metropolis located at the mouth of the Yangtze River is one of China’s most important economic centers. Its surrounding provinces are also home to numerous hotspots of large and small companies, for which Shanghai serves as hub. The city’s port is its gateway to global trade. German companies also produce on a large scale in the region.

The indefinite shutdown of such a location has significant impacts on GDP, the supply chain – and the mood. A snap survey by the German Chamber of Commerce in China made that very clear on Thursday. According to the survey, the war along with the Covid outbreak put a massive strain on logistics. For half of the companies surveyed, expected deliveries have already failed to materialize. Only 7 percent have not yet experienced any disruptions. One-third are postponing planned investments. For 46 percent of the companies, the Chinese market has become less attractive. Above all, executives lack guidance on how China’s pandemic policy will continue in the long term.

Meanwhile, the official Purchasing Managers’ Index for the Chinese industrial sector fell by 0.7 points to 49.5, and the index for the service sector fell by as much as 3.2 points to 48.4, according to the National Bureau of Statistics in Beijing on Thursday. The highly observed indicators thus fell below the important mark of 50, which means sentiment among companies is poor. They expect their business to shrink. “The economic situation in China has obviously been clouded by the current Omicron wave,” wrote Commerzbank analysts Hao Zhou and Bernd Weidensteiner.

The return of the pandemic is clearly seen as the reason for the drop in sentiment. “Recently, clustered outbreaks have occurred in many places in China,” Zhao Qinghe from the National Bureau of Statistics explained the negative trend. But the Ukraine war also plays a role: “Coupled with a significant increase in global geopolitical instability, production and operation of Chinese enterprises have been affected.”

The problem with Omicron: While the original variant and Delta could be kept in check with a close tracing of infections, the new variant slips through the net much easier. It spreads faster and more aggressively. Since zero covid is now government doctrine, local administrations will have to crack down on the virus with ever more severe measures.

Shanghai’s automotive industry has already suffered considerably. Volkswagen had to shut down production at its joint plant with SAIC. Toyota and Tesla also report stoppages, as do numerous suppliers. But it is not just production that has suffered; sales also stall when more than 70 million people are sitting at home already. The lockdowns have “an immediate effect on deliveries,” Bloomberg quotes Brian Gu, President of EV start-up Xpeng.

At the same time, the German industry remains dependent on intermediate supplies from Asia. Almost half of the companies surveyed are reliant on components from China, as the Munich-based Ifo Institute revealed in a recent survey. At the same time, it shows that the private sector is actively pushing for decoupling. Of the particularly dependent companies, half plan to reduce their imports from China in the future.

Unlike in 2021, this year could also see stagnation in the other direction. Not only imports from China, but also sales in China are at risk when its economic engine sputters. Aside from Corona, higher raw material prices could also weigh on the bottom line. “Cost pressure for the manufacturing sector is rising significantly again,” Commerzbank experts noted. This increases the risk of stagnation of the Chinese economy.

Omicron is thus currently a political and economic problem in China, while it is a medical problem in Germany. China is rightly trying to prevent it from becoming a medical problem in the first place. The question is whether that is possible at all. Normalization only occurs when there is a high level of immunity among the population, which presumably requires several infections for each individual on top of proper vaccination. However, China is currently not pursuing this path of massively increasing immunity that vaccination with mRNA vaccines would provide.

Chinese consumers continue to feel the economic impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine at the gas pumps: Thanks to rising global oil prices in the wake of the war, gasoline and diesel cost more in the People’s Republic than they have since at least 2006. As of Friday, price hikes of 110 yuan per ton of both fuels will again apply, according to the National Development and Reform Commission. Authorities had already raised prices several times since the Ukraine war began. The rise in crude oil has prompted China’s independent refiners to cut production. China’s three largest oil companies-China National Petroleum Corporation, China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation, and China National Offshore Oil Corporation have reportedly been asked to maintain oil production and facilitate shipments to ensure a stable supply. ari

The political shuffling within the Chinese Communist Party continues: Ying Yong, Party Secretary in the province of Hubei province, has resigned from his post “for reasons of age,” state officials announced. Ying, a Xi Jinping loyalist, turns 65 this year, reaching the usual retirement age for provincial officials. His resignation came as a surprise to many, as he had long been considered a potential candidate for higher positions. Ying, former mayor of Shanghai, had been appointed Party chief of Hubei at the height of the Covid outbreak. The virus first appeared in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei. He will now be succeeded by Wang Menghui, who was previously China’s minister of housing and urban-rural development.

There are also changes in two other provinces. Xin Changxing is the new Party chief of Qinghai. Liang Yanshun took the position of Chun Runer as the highest Party official in the Autonomous Region of Ningxia.

Before the National People’s Congress begins in autumn, the changes within China’s Communist Party are being closely watched. Since the start of the lockdown in the megacity of Shanghai, eyes are also on Li Qiang, Secretary of the Shanghai Communist Party. Li is considered a close ally of President Xi. He was considered a hot contender for a post on the Politburo Standing Committee. But the deteriorating Covid situation in the economic hub may have now cost Li a promotion. ari

“Study history!” China’s sole-ruling Party leader Xi Jinping has repeatedly urged his compatriots since he took office at the end of 2012. As early as March 2013, he urged, “Take history as a mirror” (以史为镜): “Learn from the historical experience of our party and country (来龙去脉).” That is particularly important “for creating the future, because history is the best textbook.” (历史是最好的教科书).

Beijing is not concerned with the noble goal of educating China’s population in matters of historical truth. On the contrary, Xi openly admits that he wants to reinterpret the history of his Party and the development of the People’s Republic, as well as revise textbooks and curriculum in schools and universities accordingly. The Party demonstrated what this looks like in honor of its 100th anniversary in 2021. Xi downplayed the former persecution campaigns under Mao as an unsuccessful attempt to find new ways. He even relativized Mao’s destructive Cultural Revolution or erased crimes committed by the Party leadership, such as its Tianan’men massacre in 1989, from public memory. Those who insist on depicting history as it actually happened are complicit of “historical nihilism”. Legally, this is a criminal offense.

Last year, Beijing was no longer content with merely retelling history. He wanted to change it, Xi promised in a January speech to the Party School: “Time and momentum are on our side” (时与势在我们一边). Under this guiding principle, he mocked the “end of history” proclaimed by political scientist Francis Fukuyama in 1989 after the collapse of the Soviet bloc. Time had put a true “end” to rash judgment. China, on the other hand, is entering a “new era” and will write the history of the future.

Yet China’s leadership had once tried to jump over its shadow. In 2006, a diplomat friend handed me an illustrated 670-page volume of selected historical documents published by the Beijing Foreign Ministry Archives. The gold-colored cover read, “Declassified Diplomatic Documents 1949-1955.” He praised it to me as a sign of “more openness and transparency of our history.”

The background: Beijing authorized a review of the development of the People’s Republic with the help of original historical sources. Provinces and the foreign ministry were allowed to open their archives for this purpose. In 2004, China’s Foreign Ministry for the first time released thousands of internal documents on events dating back decades for, free for the public to see. In 2006, it unsealed another 25,651 files covering the period 1956 to 1960. Renowned historian Shen Zhihua, a conflict researcher on Chinese Cold War history at Shanghai University, praised the opening of the archives as a “flower in the garden of Chinese reform.”

Even though the archive published only a third of its records and kept official documents on foreign policy decision-making under lock and key, Shen found pieces that shed new light on Beijing’s behavior during the Korean War (1950 to 1953) and explained why Mao – as the victor of the civil war – was unable to annex Taiwan in 1950. They also shed light on Beijing’s once rocky relationship with its “big brother,” the Soviet Union, which led to the sudden withdrawal of all Soviet experts from the People’s Republic in 1960. The subject has again regained relevance, as China and Russia celebrate their supposedly best friendship and cooperation of all time.

This much transparency made waves internationally. Christian F. Ostermann, Director of the Woodrow Wilson International Center in Washington, called it an “archival thaw in China”. His special documentation on the “Cold War in China,” published in 2007, was the first to analyze China’s documents in addition to the sources from the archives in Moscow and Eastern Europe, which have been open since 1992.

The thaw lasted only a few years. Beijing did not release another volume of declassified documents. Researcher Kazushi Minami of Japan’s Osaka University writes: “But as Xi Jinping came to power, the Chinese government abruptly closed the FMA in 2012.” It has been opened only sporadically ever since. 90 percent of its once-accessible documents were again locked away.

When Minami visited the archive in July 2017, he was almost alone there. He felt that “researchers are unwelcome. I felt I was under constant supervision.” The 19th Party Congress in 2017, where Xi asserted his absolute rule over the Party and the country, had cast its shadow. “China seems determined to rewrite the past. It all starts with the archives. It’s unlikely that the Xi government will loosen its control over valuable historical sources anytime soon.”

International scholars owe new insights into what once happened in China not only to open archives. They were able to, like Frank Dikoetter, who researches Mao’s campaigns, use memoirs of historical witnesses that emerged en masse in the pre-Xi era, writes Wilson Center historian Charles Kraus. Discoveries also can be made in China’s still-unregulated secondhand book and collector markets, where old diaries, private dossiers and vintage photographs are still on sale today.

Some memoirs hide revelations, as in the 2012 chatter of Wu Liandeng, the functionary who managed the Great Chairman’s household until Mao’s death, published by the Beijing Central Committee Documents Publishing House. His anecdotes show how the dictator often revealed much about his moods and true view of things over meals, including his resentment of Soviet leaders.

In July 1962, when Mao was served a curry goulash with beef, he took it as an opportunity to mock the Soviet CP leader. The latter had elevated “goulash communism” to a social ideal, where every Soviet citizen would be served potatoes with beef once a day in the future. Laughing, Mao feasted on the curry: “Let’s eat Khrushchev now.” While doing so, he insulted Moscow’s leader, who had withdrawn all Soviet experts from China. “They want to strangle us with this. I don’t think the world will stop spinning if China breaks with the Soviet Union.” The cynicism the dictator displays in this dinner scene is boundless. A year earlier, millions of farmers had starved to death thanks to his utopian Great Leap Forward.

In another scene, officials wanted to offer freshly caught sparrows as a roasted delicacy to Mao, who had visited Wuhan in the summer of 1958. Mao was irritated and asked how this was possible. After all, he had been assured that the feathered “evildoers” had been completely exterminated on his orders. “These few are the only ones left,” his hosts express themselves, frightened. But Mao was in a good mood: “Then let’s exterminate them together for good.”

Two years earlier, one of the most absurd mass campaigns had raged through China. Mao had ordered the “eradication of the Four Evils,” the quartet of pests which included the rat, mosquito, fly, and the sparrow. The dictator had heard that a sparrow would steal up to four pounds of grain per year. To prevent a threat to China’s food supply, he mobilized six hundred million Chinese to exterminate what was then estimated to be four billion sparrows.

In September 1957, Mao put the issue on the agenda of his eighth party congress and demanded: “China must become a country in which there is no longer a single one of the four pests.” Nationwide and collectively, a hunt was called. Its peak was in 1958, when authorities across China recorded the deaths of 2.11 billion sparrows. Mao only called the hunt off when he learned from researchers at the Academy of Sciences that sparrows were primarily killing plant pests and when he read reports from his agricultural officials how his campaign was further damaging the forestry industry in the midst of an agrarian crisis. They were removed from the list of four pests and replaced by cockroaches.

According to Xi, the end of history today applies only to the declining United States and the West, but not to the rising People’s Republic, which has the future in its hands. Beijing glorifies its past and does not want to see any documents from its archives that say otherwise, nor does it want to be reminded of its insane campaigns against the sparrows. It also does not want to know what Russian researchers like Alexander Pantsov claim to have found in the Moscow archives. To speed up the recovery of the almost completely decimated sparrow population, Beijing secretly had more than a million Siberian sparrows imported from the arch-enemy Soviet Union in the early 1960s.

It took the Beijing court three hours on Thursday to discuss the case of Cheng Lei with the defendant in person. Three hours were enough for the Chinese judiciary to make a final assessment of the serious charge of leaking government secrets. This tiny short period contrasts with the long uncertainty in which the mother of two had previously been held. After all, the Chinese court had taken a long time before putting her on trial on Thursday.

The Australian woman with Chinese roots was detained 19 months ago. For almost half a year, her whereabouts were unknown. Neither did anyone know why she had been arrested in the first place. This was legal under Chinese law: police can place suspects under RSDL (Residential Surveillance in a Designated Location) for up to six months. During this time, they do not have to provide her with a lawyer or inform anyone about her whereabouts.

It was not until August 2020 that Chinese authorities informed their Australian colleagues that Cheng Lei had been formally arrested and accused of leaking secrets. The case made waves. Not only in the international community in Beijing, where the single mother readily offered private advice on which preschools were best for foreign families, but also in many parts of China, Australia and much of the political West.

Cheng had worked for China’s state broadcaster CGTN for eight years. She was known to the public as a news anchor. She never made a secret of the fact that she valued the liberal spirit of democratic systems. She once appeared as a “global alumni” in a promotional video for Australia as a university destination, aimed at young Chinese. Australia’s education system “doesn’t teach you to just follow instructions, it allows you the freedom to make up your own mind,” she said in the video.

She continued to express her own thoughts during her time at CGTN. As an Australian citizen who had emigrated from China to Down Under with her parents when she was nine years old, she did not miss any opportunity to criticize President Xi Jinping or the Chinese government’s early Covid policy on the Internet. It is not certain whether these statements had anything to do with her later arrest.

Although Chinese state media strictly adhere to public announcements by the government in their reporting, information leaked out via social media. About a year ago, a WeChat user named “Beijing small sweet melon” took up the case, revealing astonishing details about Cheng Lei’s private life and the allegations against her.

Above the post it said, “Betraying her motherland, how did CCTV famous anchor Cheng Lei become an Australian spy?” And further down, the post reads, “China has given you everything, yet you counterattack as a tool of the enemy.” More posts on social media from other accounts with pseudonyms about the case followed shortly after, all with the same tenor. Later, a video surfaced, “Spy CCTV anchor Cheng Lei: For 20 years she hid in state television, stole state secrets, now after being detained, shamelessly claims injustice.”

It is highly unlikely that such posts appear randomly on such high-profile state matters in a tightly controlled surveillance state. “These posts are written by Ministry of State Security (MSS) people to set the public tone,” Feng Chongyi of the University of Technology Sydney told Australia’s ABC radio. Feng had been detained himself for a week during a visit to China four years ago.

After Cheng Lei’s formal arrest, Australian diplomats were allowed to communicate with her once a month via video phone calls. The topics, however, were chosen by the Chinese authorities. Australia’s Ambassador Graham Fletcher was even denied entry to the courtroom on Thursday. The Australian government had asked for a minimum rule of law in the run-up to the trial.

The biggest victims of the case, however, are probably the two twelve- and ten-year-old children of the 46-year-old. The mother had brought her daughter and son to their grandmother’s home in Melbourne shortly before she disappeared. Due to the Covid outbreak in China, Cheng Lei had decided on short notice to take the two out of the country. They have not seen their mother for more than a year and a half.

In the worst case, this situation could continue indefinitely if the judges hand down a life sentence. This is possible, but not likely. The usual sentences for such charges are five to ten years in prison. A possible conviction and sentence will be announced by the Chinese court at a later date. Usually, they are in less of a hurry than during the trial itself. Marcel Grzanna

Inga Heiland will take over the management of a research center for trade-related topics at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy on April 1, 2022. In this position, Heiland will conduct research on global container shipping and global supply chains, among other topics.

Dennis Kraemer joined Daimler Greater China in Zhenjiang earlier this month as Battery Cell Launch Specialist. Kraemer was previously Outbound Logistics Specialist in Aguascalientes, Mexico, also for Mercedes-Benz.

Tobias Beck has moved from Beijing to Shanghai for the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. He also works there as a Project Manager and Research Fellow.

These tiny dots in the steppe are chirus. In fact, there are 10,000 of them. When so many of the goat-like animals gather as they do here in Gêrzê County in the western part of the Autonomous Region of Tibet, it’s good news. These animals have become rare. At present, their numbers are slowly increasing again. Chirus are also called orongos or Tibetan antelopes.