Sometimes it is just wishful thinking. The wish, which is certainly particularly widespread in the Western world at the moment, is to find a mediator who will bring the warmonger Putin to his senses. And the derived thought is that Xi Jinping could be this mediator.

Since the start of the Ukraine war, speculation arises at the slightest hint that China might change its stance on Russia and move away from its partner Russia. During Scholz’s visit to Beijing, for example, Xi’s statement on the use of nuclear weapons was seen as such a hint. At the G20 summit, what had been dreamed of seemed to be confirmed: The joint final declaration condemned Russia’s actions.

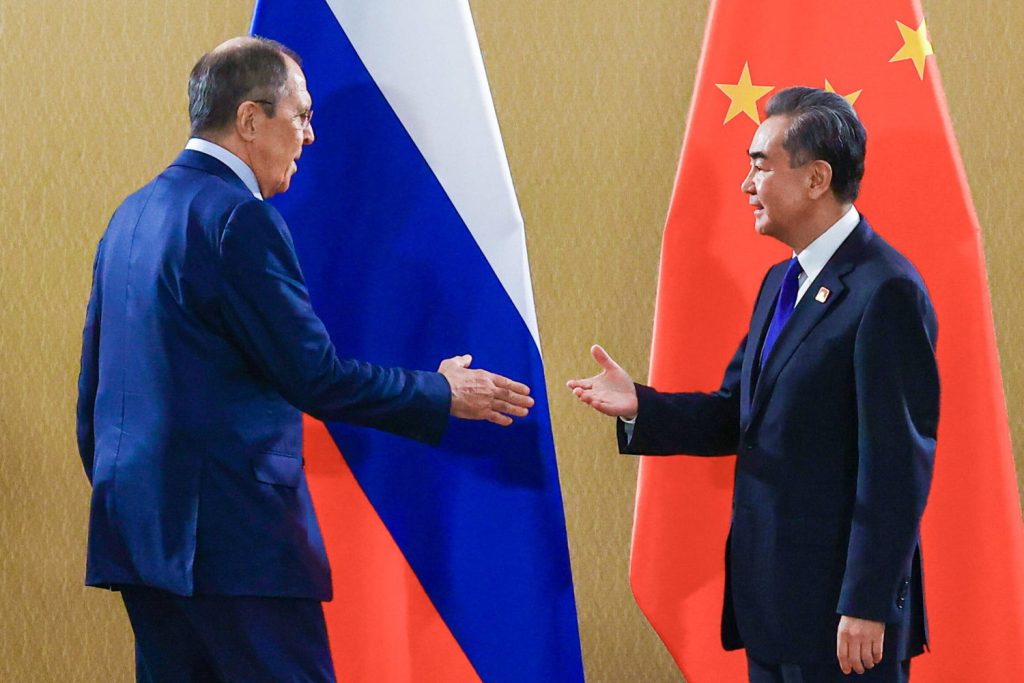

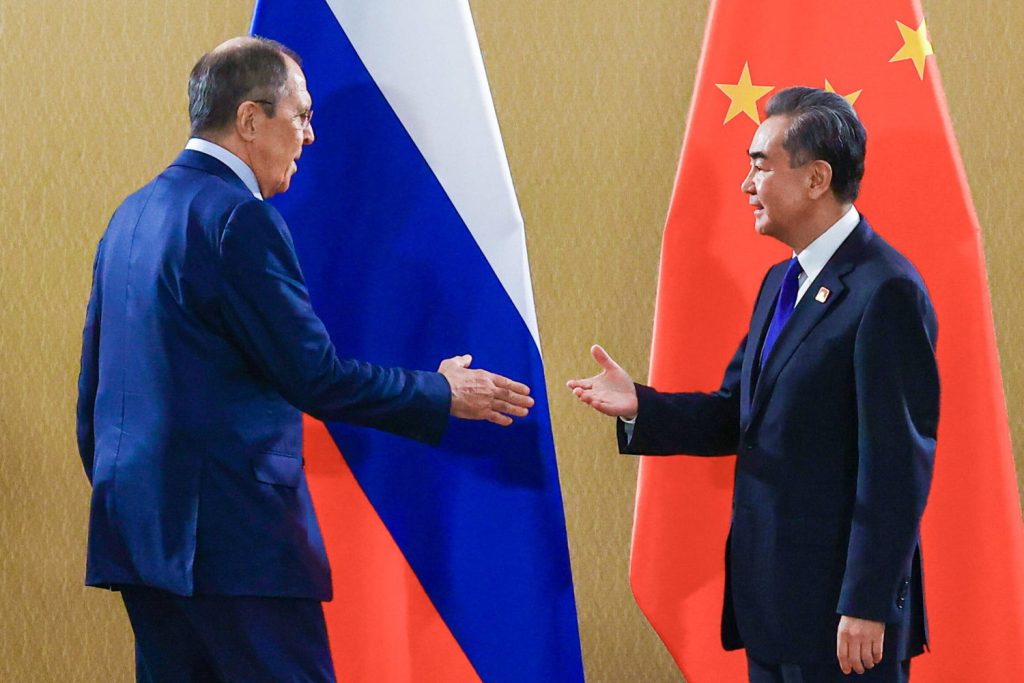

But those who followed the G20 closely caught conflicting signals. Foreign Minister Wang Yi assured his Russian counterpart Sergey Lavrov that cooperation will go even further in the future. He titled the Russian war of aggression merely an “Ukraine issue.” Fabian Kretschmer analyzes China’s true attitude toward Russia.

There is also a truth behind the truth in the architecture of the Chinese state. The executive power in China – as in other countries – theoretically lies with the state organs. Xi Jinping, however, has gradually shifted all important tasks specifically to the party. A network of party commissions and working groups forms a parallel structure to state institutions and exerts significant influence, reports Christiane Kuehl. Merics researcher Nis Gruenberg gets to the bottom of the system in a new study.

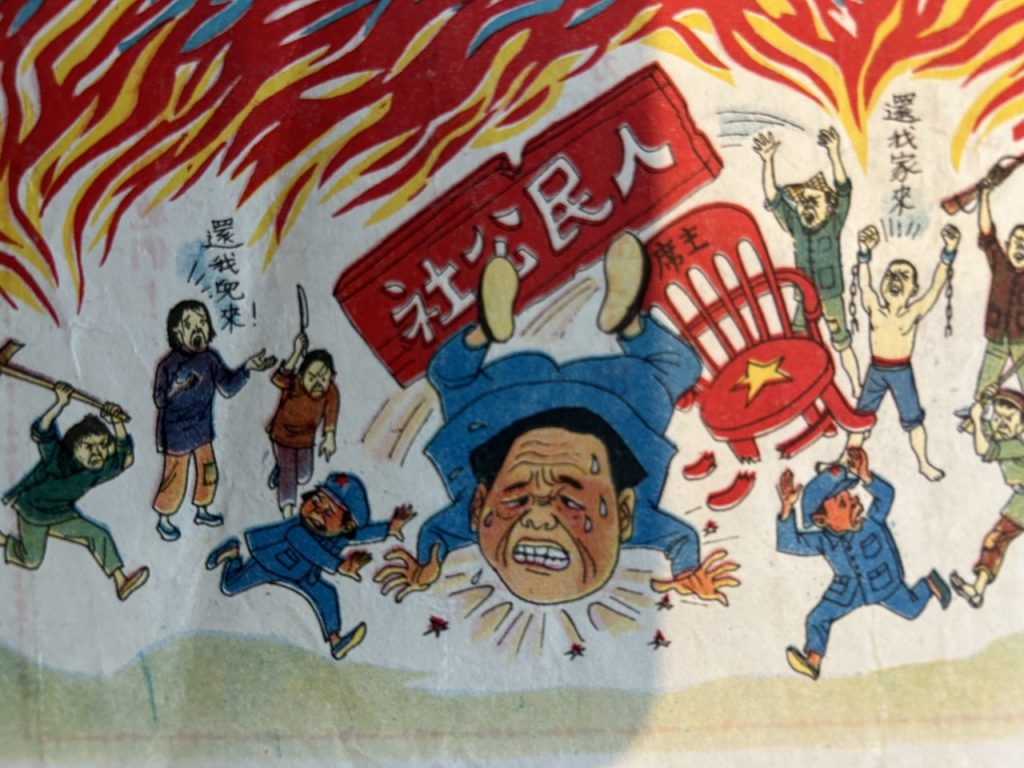

A visit to the flea market can be like a treasure hunt. Maybe a long-desired record or an unrecognized designer lamp is found that makes the heart sign with joy. Until recently, Chinese flea market visitors could even stumble across politically explosive finds: rare contemporary historical documents. Photos of the Tiananmen massacre, for example, writings critical of the regime, or political flyers from the 1950s. Some of the collectibles were sold to flea market traders by the Chinese authorities themselves, reports Johnny Erling – a treasure hunter of exciting stories.

The 20th Party Congress in October cemented state and party leader Xi Jinping’s status as the absolute center of power. For ten years, Xi has been concentrating the control of politics in his hands behind the scenes of the party. To this end, starting in 2012, he established a network of so-called Leading Small Groups (LSG/领导小组) and Central Commissions (中央委员会) in the Communist Party for a wide range of policy areas, such as the economy, the environment or innovation. For most of them, Xi also made himself head.

In theory, executive power and legislation in China also lie with the power of the state organs – the State Council, ministries, and the National People’s Congress. But Xi specifically brought these functions into the party with the help of the new commissions. Today, the CP has a parallel structure to state institutions. LSGs are ad hoc bodies that are supposed to coordinate limited tasks across administrative boundaries. Central commissions, on the other hand, function as permanent political supra-ministries, as Merics experts Nis Gruenberg and Vincent Brussee analyze in a recent study. This system could indeed accelerate and better coordinate some measures, the two researchers write. But it does so at the expense of “transparency, accountability and flexibility.”

A special role in this system is played by the Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform/CCDR/中央全面深化改革委员会, through which Xi aims to accelerate structural reforms. “The CCDR is a little more special than the other commissions in the CP. It meets more often, is more involved in decision-making processes, and has firm access to bureaucratic support from party headquarters,” says study author Gruenberg. It is attached to the party’s central think tank, the Central Policy Research Office (中共中央政策研究室), which is responsible for researching and writing important documents and speeches and is based in the “General Office,” the party’s nerve center (中国共产党中央委员会办公厅, 中办 for short). So the way to the boss is short.

The CCDR was initially founded at the end of 2013 as a small leadership group, i.e. an LSG, and upgraded to a commission in 2018. In parallel, the party transformed other LSGs into commissions at that time, such as those for Finance and Economy, National Security, Foreign Affairs, and Cybersecurity and Digitalization. The goal: to “strengthen the role of the CCP’s central bodies in policy-making and coordination.” With the commissions, Xi reversed the decoupling of state administration and the party that was advanced under Deng Xiaoping, Gruenberg says. “The organization of the party and the administration are now tightly intertwined. While the State Council is responsible for implementation, policy design is now in the hands of party commissions.”

The fact that Xi demonstrably chairs at least ten commissions and LSGs himself gives their decisions greater urgency, the researcher says. “Xi sits in all the meetings of these bodies.” In this regard, he says, the CCDR is Xi’s personal reform catalyst, because with its help he can push through his priorities more quickly. “The CCDR is thus effectively a reform ministry of the CCP.” Reform, that doesn’t sound much like Xi Jinping. But the word ultimately means only a change in previous structures – not automatically a liberalization.

The CCDR is organized into six subgroups to coordinate with relevant ministries:

One of the CCDR’s goals has been to coordinate state institutions that sometimes compete with each other, Gruenberg says. “Xi was upset in 2012 about the reform backlog in Hu Jintao’s government. He wanted to break that up, so he set up all these commissions.” Today, there are thousands of representations of these commissions and LSGs at all administrative levels and in all state-owned enterprises, down to local governments.

But how do these intransparent CP groups function on a day-to-day basis? According to Gruenberg, finding details about the CCDR’s activities is like detective work since there are only a few publicly accessible documents about them. Basically, however, the process is always similar. Each year, the CCDR sets out the main reform priorities in its annual work plans (工作要点). Then it assigns, for example, a ministry to prepare specific plans or legislation for a particular agenda item. This goes back to the CCDR for approval – which then either makes further recommendations in a kind of “feedback loop,” or publishes the plan in a document. This is special because “these documents are then immediately considered ‘enacted law.’ They are binding even though they haven’t even gone through the state’s legislative process yet,” Gruenberg says.

Xi presents himself as a micromanager of everyday politics. One example of the issues: At its meeting on September 8, the CCDR, chaired by Xi, discussed and adopted five documents:

One of the CCDR’s main focuses is environmental policy. “The structural change to a circular economy is an important priority for Xi,” says Gruenberg. For example, the CCDR adopted an ‘opinion’ (意见) on the key points of waste separation, kicking off the relevant regulatory process.

According to Gruenberg, it was also the CCDR that decided China’s import ban on plastic waste. The state only formally adopted the ban afterward. The CCDR also played a leading role in setting up China’s system of national parks, according to Gruenberg. For this, “we found clear references to the flow of feedback between ministries and the CCDR.”

Special committees with specific ad hoc tasks, such as the organization of the Olympic Games, can certainly ensure efficiency. Problems arise when these structures become permanently entrenched, says Gruenberg – in other words, when the LSGs in China become central commissions and more and more power is concentrated in the direction of the party leadership: “As a result, we now have the situation that Xi has to take responsibility for everything himself. Today, you have to assume that something will only happen if it is initiated from above.”

Gruenberg expects the system to continue, even if Xi no longer has to fear any rivals in the government from March 2023 at the latest: Premier Li Keqiang, who Xi dislikes, is then expected to be replaced by his loyalist Li Qiang. The CCDR may continue to be a driver of administrative reform. “But at the same time, it sucks resources out of the agencies, all of which have put a lot of energy into Xi’s priority policies,” Gruenberg says.

Xi dominates the bureaucracy by cramming the system full of instructions. “In addition, prioritizing central requirements inevitably leads to prescribing solutions that are less adapted to local conditions than if they were worked out locally,” the expert said. “In highly heterogeneous China, this is a problem.”

For the West, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has long been persona non grata, but his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi greeted him with a handshake and a warm smile at the G20 summit in Bali on Tuesday. A look at the pictures after the fact counters the perception that emerged from the joint final declaration, which criticized Russia and was also supported by China.

What the two said to each other was probably felt bitterly by European politicians. Wang Yi pledged to “deepen pragmatic cooperation with Russia” and promote a “multipolar” world order. The Russian war of aggression was simply dubbed the “Ukraine issue.” The two sides sounded exactly like in state media reports at their previous meeting in September.

Only one of Wang’s statements can be interpreted – with a lot of goodwill – as a slight deviation from the usual line: China positively registered that Russia recently confirmed its “rational and responsible attitude” that nuclear war should never be waged.

Since February, the political West has been paying attention to every syllable that Chinese government representatives address to Russia. Most recently, they were thrilled by supposed commitments that Head of State Xi Jinping made to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz. China will “reject the use and threat of nuclear weapons” – back home, Scholz sold it as a powerful new concession.

After all, these were the most critical words from Beijing to the Kremlin since the beginning of the war. But the perception in many Western media that the Chinese leadership has finally come to its senses and moved away from Moscow is an overreaction. The nuclear statement simply reiterated an established guiding principle of Chinese policy.

So far, there are no real signs that China is changing course. Xi Jinping’s statement was not even remotely indicative of this: the statement was vague and Russia was not even mentioned directly. And during Xi’s G20 summit meetings with US President Joe Biden and French President Emmanuel Macron in Bali, the rejection of nuclear weapons was not repeated by the Chinese.

One thing is certain: The People’s Republic continues to walk a delicate tightrope. To the outside world, it presents itself as a neutral peacekeeping nation committed to negotiations and talks. In reality, however, it has taken Russia’s side. While Xi promised Vladimir Putin “boundless friendship,” he has not even spoken to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Selensky on the phone since the war began.

Moreover, the official state media continue to adopt Russian propaganda – with minimal changes. The People’s Daily newspaper, for example, says that the “nuclear threat theory is being played up in the West” and that Russia would only use its nuclear weapons for self-defense. CCTV evening news Xinwen Lianbo recently even identified Ukraine directly as the main culprit for the missile strike in Poland. And behind all the developments is an aggressive NATO under Washington’s leadership.

When the United Nations voted on a resolution to “provide a basis for future reparations payments from Russia to Ukraine” this week, China – along with Syria, North Korea, and Iran – voted against it. India, which has also been criticized by the West for its pro-Russia stance, on the other hand, abstained from the vote.

Of course, China’s relationship with Russia is not set in stone but adapts to the situation. In the case of a G20 final declaration, it does not like to be made an outsider. But the range is otherwise rather narrow: Beijing’s strategic interest in reshaping the world order according to its ideas continues to prevail over short-term disgruntlement. And to break through Western hegemony, led by the United States, Chinese logic says that Russia is absolutely necessary as an international partner.

That the use of nuclear weapons is a red line even for the Sino-Russian alliance of convenience remains true; it would hardly benefit the planned transformation of the global order. But such a stance should be a matter of course – and does not deserve international applause. Fabian Kretschmer

Nov. 21, 2022, 08:30 p.m. (Nov. 22, 2022, 3:30 a.m. Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, book launch and discussion: Overreach: How China Derailed its Peaceful Rise More

Nov. 22, 2022, 1:30 a.m. (8:30 a.m. Beijing time)

Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Webinar: Performing the Ecological Fix Under State Entrepreneurialism in China More

Nov. 22, 2022, 03:30 p.m. (10:30 p.m. Beijing time)

Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Webinar: Sarah Mellors Rodriguez – Birth Control and Abortion in China More

Nov. 22, 2022, 8:30 a.m. (03:30 p.m. Beijing time)

China Network Baden-Württemberg, Business Talk: Lockdown as a continuous loop – experience and learning process More

Nov. 23, 2022, 9 a.m. (4 p.m. Beijing time)

Dezan Shira & Associates, Webinar: Global Supply Chain Disruptions and Transfer Pricing: What to Know for Your China Operations More

Nov. 24, 2022 11 a.m. (6 p.m. Beijing time)

Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Global China Conversations: Expats leaving China: What are the consequences for multinationals and China’s economy? More

Nov. 25, 2022, 12 p.m. (7 p.m. Beijing time)

Confucius Institute FU Berlin, Lecture: Influence of the Ukraine War on International Relations More

The Chinese government has sharply criticized a draft of a new China strategy from the Foreign Ministry published on Wednesday. In response to a question from Deutsche Presse-Agentur in Beijing, a statement from the Chinese Foreign Ministry said that the classification of China as a “competitor” and “systemic rival” was a “legacy of Cold War thinking.” The Chinese side called the paper a “denigration of China by the German side.” It said the paper was full of “lies and rumors.”

The first confidential draft of the China strategy had been reported by Der Spiegel on Wednesday. The paper defines China as a partner, competitor, and systemic rival. If Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock has her way, human rights in particular are to play a greater role in dealings with China, and relations with Taiwan are to be expanded. In addition, economic dependencies are to be reduced “quickly and at a cost that is acceptable to the German economy.”

However, the new China strategy is still in the process of being coordinated with the other ministries, especially the Chancellor’s Office. The European security strategy is to be presented first before final adoption. flee

Great Britain wants to stop the takeover of the chip manufacturer Newport Wafer Fab by the Chinese group Nexperia after all. Nexperia is a Dutch subsidiary of the Chinese Wingtech Group. The British government had actually approved the controversial sale of the Welsh semiconductor factory in spring 2022 after a safety review (China.Table reported). Nexperia had already bought the graphene manufacturer in 2021.

Now, according to government sources, Trade Minister Grant Shapps vetoed the takeover of the UK’s largest chipmaker. Shapps said while foreign trade and investment, which promote growth and employment, would be welcomed: “Where we identify a risk to national security, we will act decisively.” Nexperia would thus have to resell at least 86 percent of its UK chip plant, Newport Wafer Fab, to avert “potential threats,” he said. The decision was based on a “comprehensive national security assessment,” he said.

According to the Reuters news agency, a senior Nexperia executive said they did not accept the concerns raised. He said they had not been raised in two previous reviews. “We are honestly shocked. The decision is wrong,” it said. Nexperia will take action against the decision. The British case is reminiscent of Elmos: the German government had recently prohibited the Dortmund chipmaker from selling its planned wafer production to the subsidiary of a Chinese company (China.Table reported). ari

A visibly charged conversation between Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and China’s leader Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Bali continues to stir talk. Xi did not criticize Trudeau, the Chinese Foreign Ministry stressed Thursday. Spokeswoman Mao Ning said, Beijing supports open exchanges as long as they are on an equal footing. China hopes Canada will take steps to improve bilateral relations, she said. The conversation did indeed take place that way, Mao confirmed. She explained, “This is very normal. I don’t think it should be interpreted as Chairman Xi criticizing or accusing anyone.”

In the video circulated Wednesday, a visibly disgruntled Xi complains to Trudeau about a lack of confidentiality following a bilateral conversation (China.Table reported). Xi’s displeasure may have been owed to media reports in Canada in which, according to government sources, Trudeau raised concerns about alleged espionage and Chinese interference in Canadian elections during a meeting with Xi the previous day. However, the meeting between the two had been scheduled off the record.

It remained open whether the two politicians were aware that they were filmed or at what point. Xi firmly shakes Trudeau’s hand at the end before showing the camera a brief standard smile as he leaves and walks out of the picture. The footage led to quite a bit of speculation. What is seen in the video – namely, a Chinese politician publicly displaying discontent in a “spontaneous” manner – is very rare, Chong Ja Ian, a political science professor at the National University of Singapore, told the French news agency AFP. He said the conversation between the two men showed that Xi “does not take either Trudeau or Canada that seriously as interlocutors.” The tone of the exchange was similar to that of a “major power” addressing a smaller one, Van Jackson, a professor of international relations at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, told AFP. “Xi’s language and body posture were not at all unusual for government officials who are on less than friendly terms – in private,” Jackson said.

The intention of one of Xi’s statements, which did not make it into his interpreter’s translation, also remained unclear. Depending on the translation, it could be understood as a threat or rather as resignation. Foreign Office spokeswoman Mao stressed that Xi had not meant it as a threat. The two politicians had conducted a “normal” exchange and had merely “expressed their respective positions.” rtr/ari

The Federation of German Industries (BDI) accused the European Parliament of a lack of practical relevance in the drafting process of the EU-wide supply chain law. “The EU Parliament seems to lack a sense of proportion for the competitiveness of European companies in the crisis,” BDI President Siegfried Russwurm said on Thursday. The scope across the entire value chain is “far removed from reality,” he said. He called for a more limited scope of the legislation, which is expected to have far-reaching effects on business in China. “Mandatory legal requirements must be limited to direct suppliers. Otherwise, they cannot be implemented in daily practice,” Russwurm said.

On Thursday, the EU Parliament’s Legal Affairs Committee dealt with a draft report on the EU Supply Chain Act. Currently, the design’s details are being negotiated within the EU institutions. Lara Wolters, the European Parliament’s rapporteur responsible for the supply chain law, emphasized that the goal continues to be coverage of the entire value chain.

In addition to the scope of the legislation, the question of how companies can be held accountable – including by those directly affected in third countries – is still open. The EU supply chain law is intended to be more far-reaching than the German one. The German supply chain law comes into force at the beginning of 2023. It is still unclear by when the EU-wide legislation will be completed. ari

Acceptance of Chinese car brands is comparatively high in Germany, especially among premium customers. This is the result of a survey by management consultants Berylls. While 25 percent of potential customers would also consider a Chinese product for a luxury-class model, the figure for the general car market is only 16 percent.

The result surprises the experts because the price actually plays a lesser role in the premium segment. This may be due to the respondents’ level of information: Around half of the premium customers believe that China’s automakers will prevail internationally. Of the other respondents, only 35 percent believe this.

A survey of China.Table conducted by the research house Civey last year revealed similar figures. Around 20 percent of respondents could imagine buying a Chinese car brand. 45 percent believed that Chinese manufacturers could gain a foothold in Germany. fin

China’s ideologues determine and direct what their citizens are allowed to know and think about the history of the People’s Republic. Since taking office, party leader Xi Jinping has scaled back the critical examination of the past that had been tolerated for three decades and condemned it as historical nihilism. School textbooks have been rewritten, media and the Internet, art, culture, and research have been censored, and past events have been reinterpreted or concealed. Nevertheless, there are many Chinese who have evaded control. They have their own archives at home with evidence and sources of the real happenings in the People’s Republic. They are lovers of contemporary history.

Inadvertently, the CP helped them complete their collections. Some 15 years after Mao’s death, ministries, courts, libraries, publishing houses, and even security agencies began to sell off what they considered to be superfluous items stored in archives and “ideological poison cabinets.” Among them: banned books, manuscripts, documents, pamphlets. Once forbidden and hidden treasures ended up at flea markets of the big cities. These became treasure troves for historians, amateur researchers, and passionate collectors, creating a kind of involuntary Chinese coming to terms with the past.

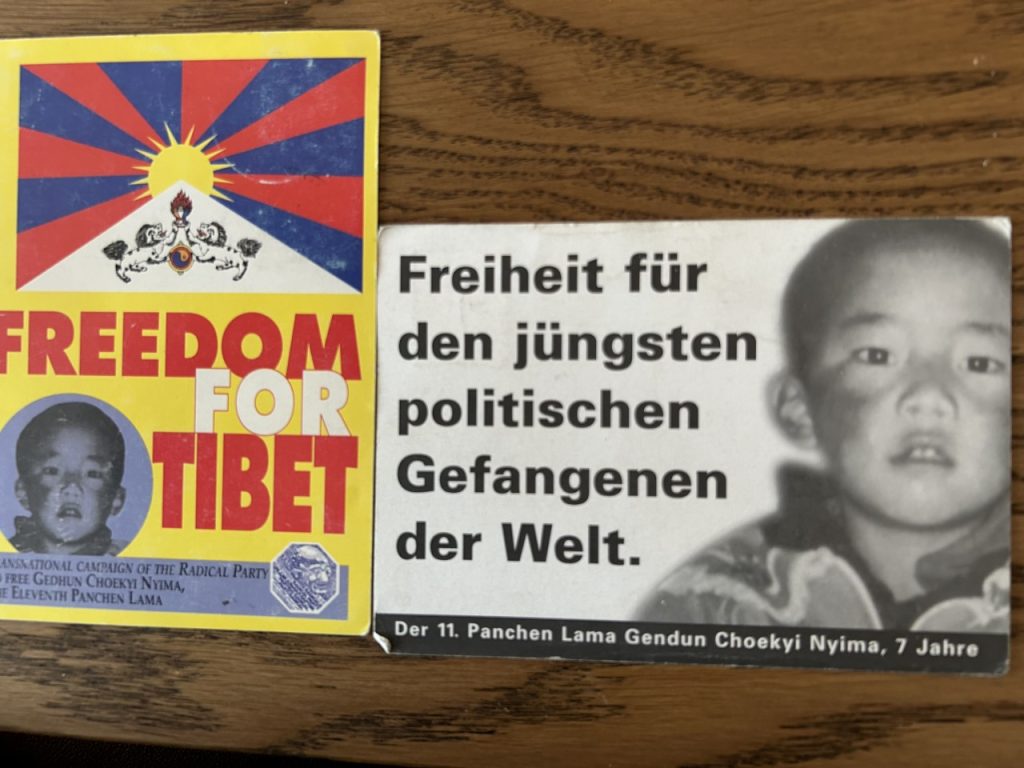

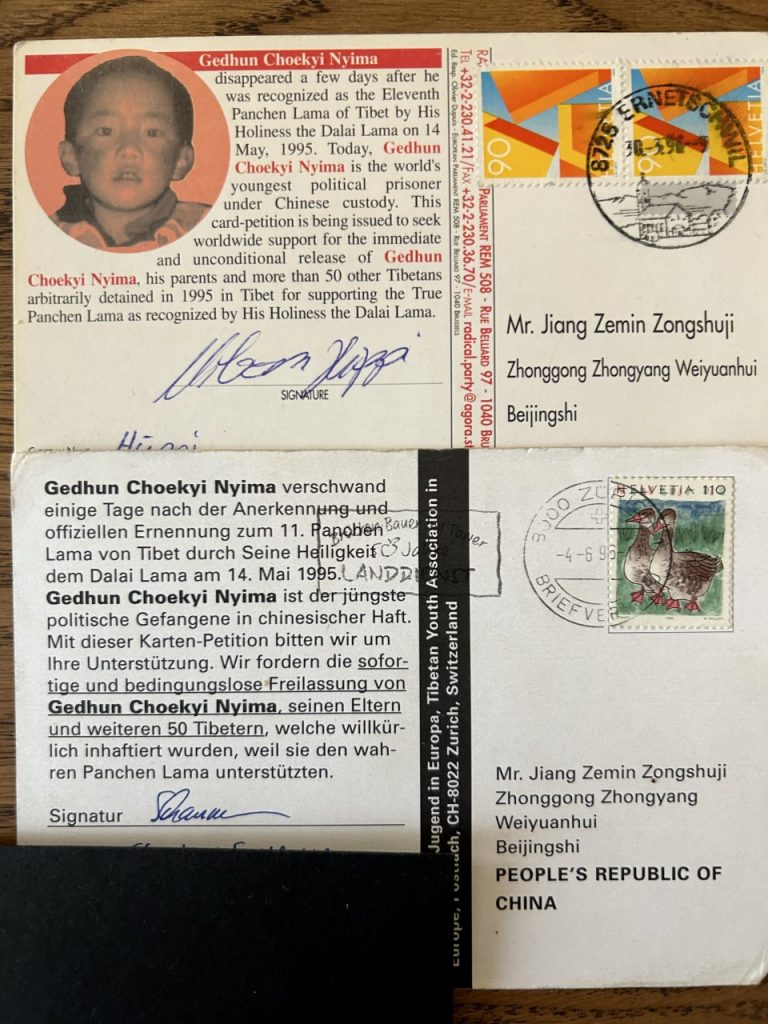

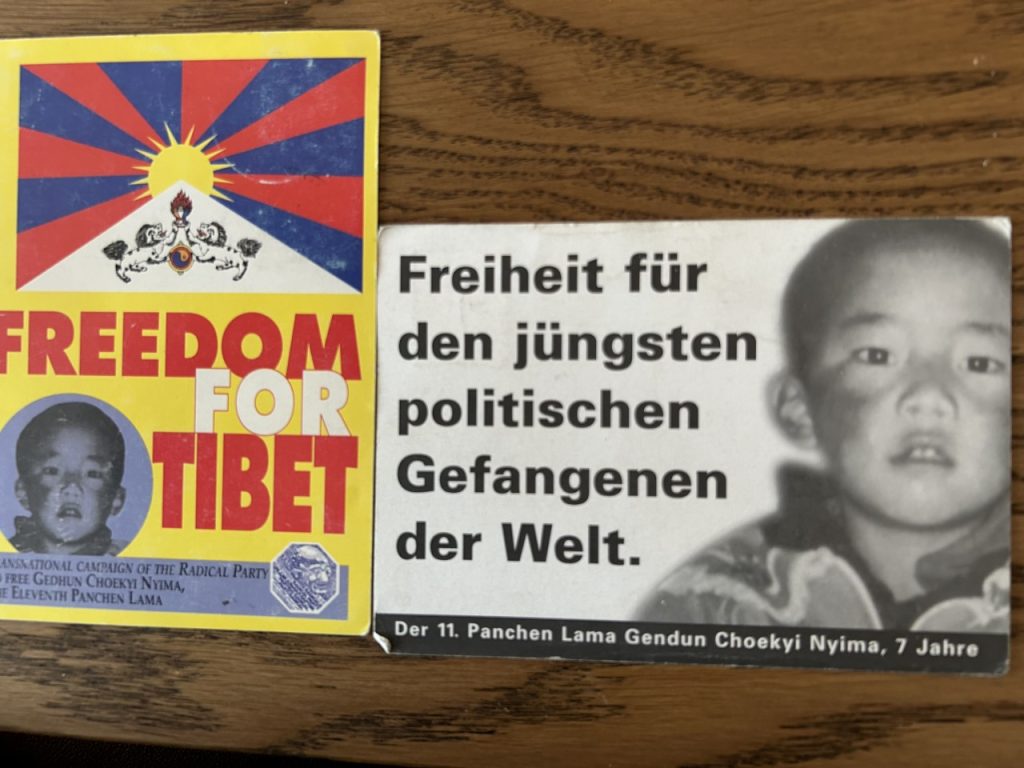

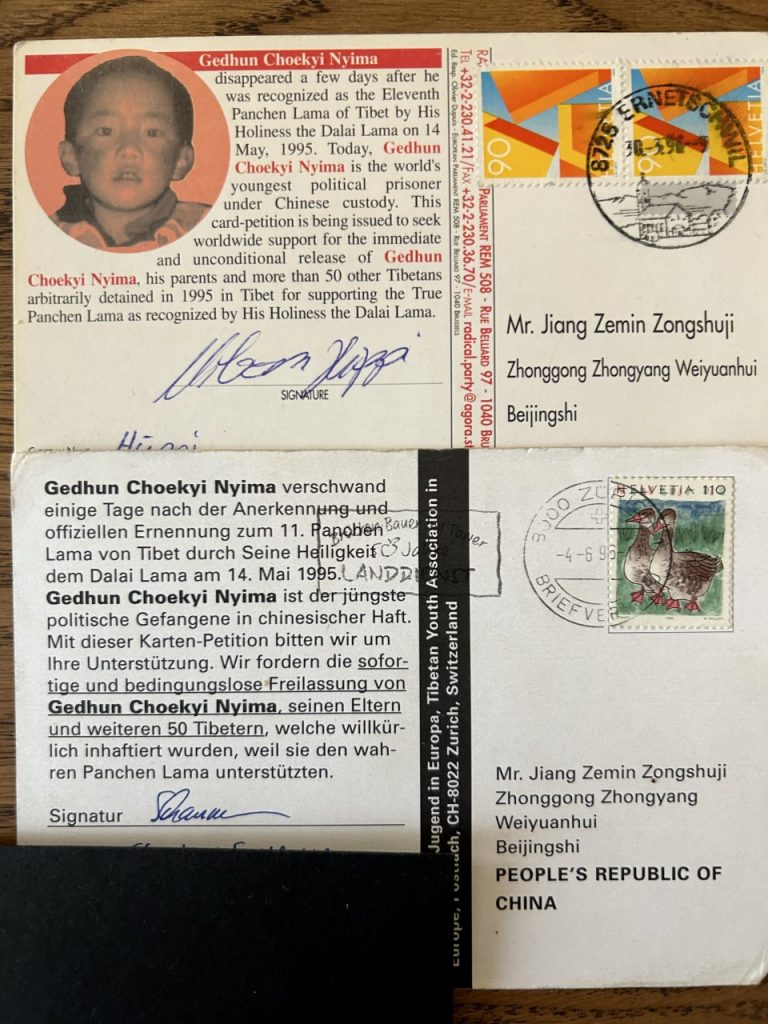

The postcards from abroad lay in packets among other collectibles on a stand at the Beijing flea market. They were stamped in Switzerland and showed photos of a boy from Tibet. German and English inscriptions demanded: “Freedom for the world’s youngest political prisoner.”

The letters of solidarity came from international Tibet initiatives, which called on citizens in Europe to express their solidarity with the boy by sending postcards to Beijing. The addressee was the then-party leader Jiang Zemin. He never got to see the postcards. The police stored them in their archives.

They accused China of abducting seven-year-old Gedhun Choekyi Nyima in May 1995, just days after the Dalai Lama recognized him as the reincarnation of the late 10th Panchen Lama. The CP condemned his religious choice, appointing another boy as the designated Panchen Lama successor and making the true successor disappear.

The whereabouts of the now 35-year-old are considered a state secret. The replacement lama appointed by Beijing, whom Tibetan believers continue to call the “wrong boy,” is allowed to visit Tibet’s holy monasteries on religious holidays, where the monks must worship him as the 11th Panchen Lama.

Gedhun’s state kidnapping (China.Table reported) and Beijing’s role in it have always been kept quiet publicly. In 2004, I saw the cards on display at a Beijing flea market for the first time. He could get a lot more of them, said the seller, who apparently didn’t even know who the boy was, but noticed my interest. Such a card costs 20 yuan. There was a discount for ten or more. He would not say anything about where they came from. One of the ten rules for Beijing’s big flea markets, like the Panjiayuan (潘家园) or the Bao Guosi (报国寺) temple market was: “Where things come from is none of the buyers’ business” (古玩交易卖家东西来自何方与买家无关).

The postcards that suddenly appeared answered the question of what happened to the many thousands of Amnesty petitions sent annually from Europe to China’s leaders. They were not destroyed but kept by the authorities.

But when Beijing ministries, institutes, and courts planned new buildings and moved around the year 2000, they cleared out their overflowing evidence rooms and state archives. Authorities parted with useless stocks of yellowing documents by the sackful. From banned, once cultural revolutionary cartoons against Mao’s inner-party enemies, to confiscated regime-critical pamphlets. Even internally classified old party resolutions, former arrest warrants and sentences, handwritten self-criticisms, or letters of denunciation were disposed of. They should have been shredded. Clever flea market dealers with connections took advantage of rampant corruption, official disinterest, and a lack of controls and bought them from the authorities, often at the price of their paperweight.

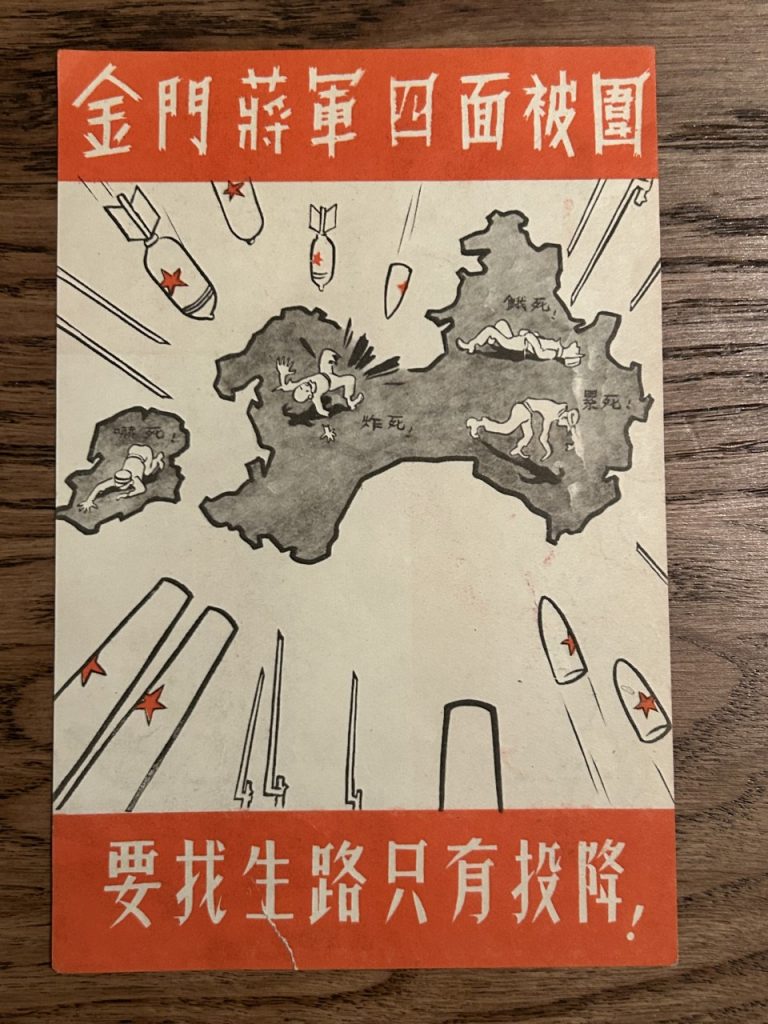

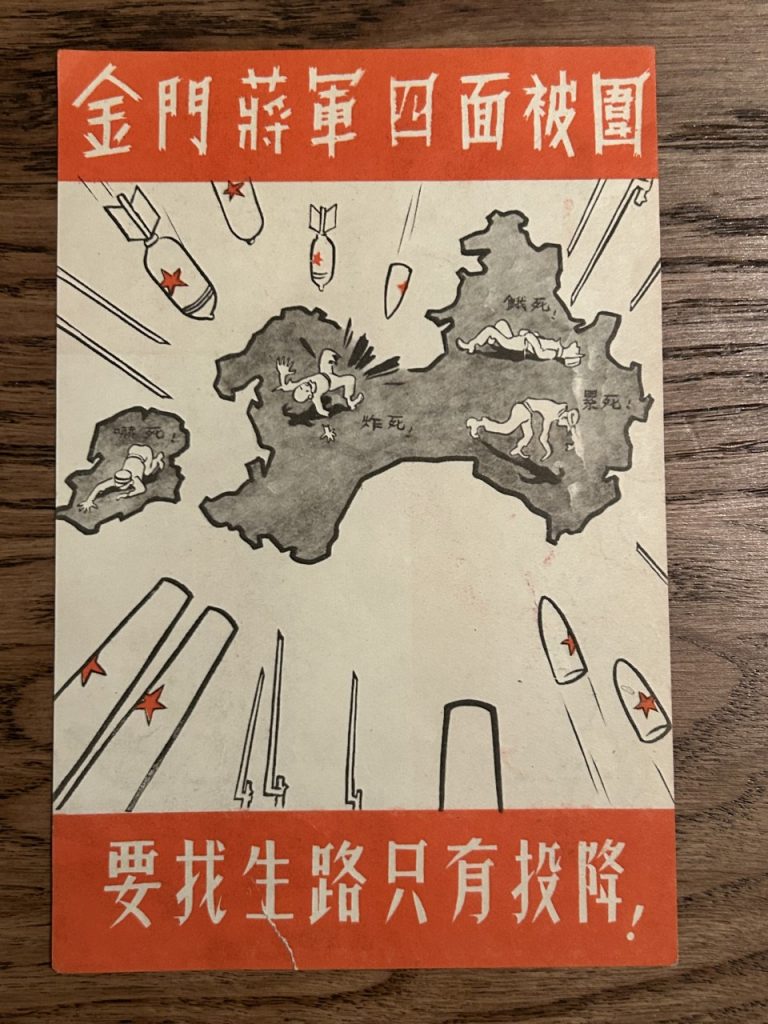

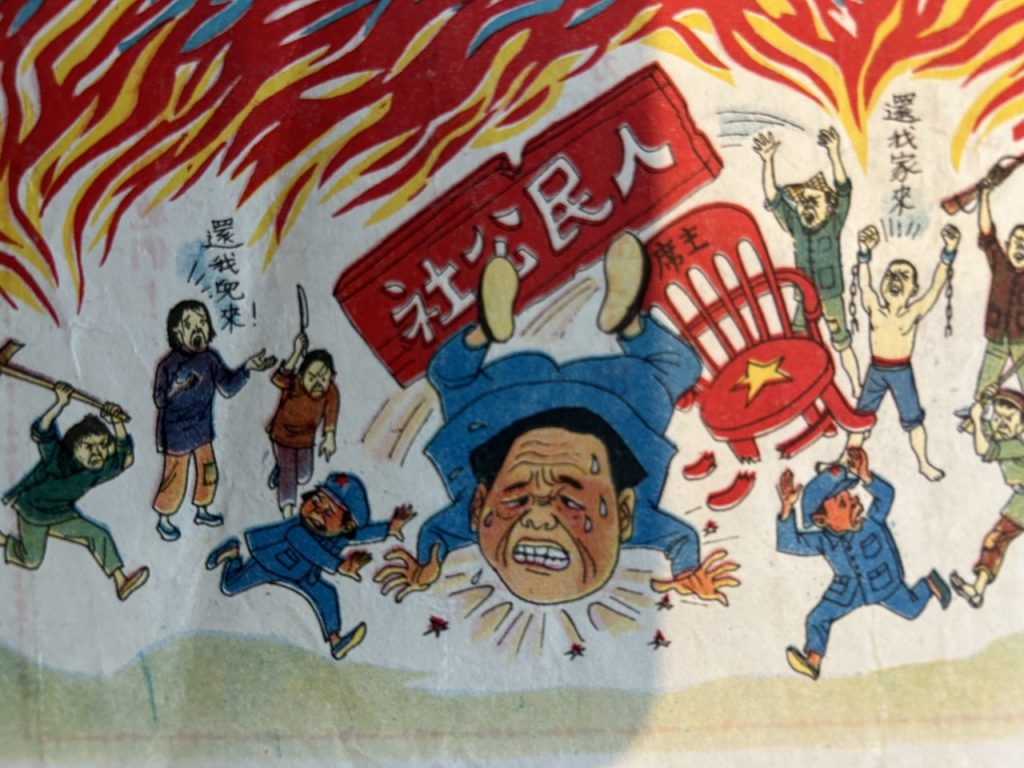

Everything that seemed useless was apparently discarded. Among them were piles of canceled leaflets from the propaganda war between the People’s Republic and Taiwan. Starting in the late 1950s, Beijing had the Taiwanese island of Qinmen bombed and repeatedly shot with propaganda shells full of leaflets. Apparently, Beijing ministries kept the receipts. These ended up in flea markets, along with leaflets dropped on China from Taiwan. Mainland citizens loyal to the state picked them up and delivered them. I saw the leaflets lying on a stand: One called on Taiwan’s islanders to surrender, the other on China’s peasants to overthrow the Mao regime.

The offer was new and met with demand: Private flea markets, which had been banned after the founding of the People’s Republic, only slowly re-emerged after Mao’s death. At first, they offered junk and old bicycle parts, tools and sewing machines. Around 1980, the first Beijing bird and flower market appeared.

Soon, there was no stopping them. Urban society became more prosperous, controls decreased. Chinese warmed up again to their traditional hobby of collecting antiques, scroll paintings, porcelain, pearls, or jade. Antique and art markets boomed.

Aside from a passion for valuable antiques, which more often turned out to be fake, enthusiasts began to take an interest in objects from their own contemporary history for the first time. They collected everything, from Mao writings and devotional objects, posters and buttons, art and kitsch from the Cultural Revolution, and China’s rationing system, to private diaries and family letters.

Old photos were also in demand. I once found photographs of Mao receiving German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and his wife Loki at his Zhongnanhai residence on October 30, 1975. The original prints had apparently been discarded because the German guest of honor was waiting with Mrs. Loki on a bench in the anteroom while Mao stood and just greeted the German ambassador at the time, Rolf Friedemann Pauls, who accompanied Schmidt. When I met Helmut Schmidt later in Beijing, I gave him one of the photos as a gift.

Some collectors specialized on the impact of Mao’s political campaigns on China, from land reform, the Great Leap Forward, to the Cultural Revolution. They found new documents in flea markets about famines, never-reported natural disasters and floods, and brutal persecution. Or Red Guard newspapers that condemned, for example, Xi Zhongxun, Xi Jinping’s father. Even internal documents and photos about the Tiananmen massacre of June 4, 1989, were on offer.

The party lost control of its narrative on history. Flea markets thus became, overnight, the only places in China that openly revealed political secrets and also provided evidence to back them up. For Beijing, it was a legal gray area.

While museums dedicated to the history of the Cultural Revolution had to close again, and the Foreign Ministry had access to its once-open historical archives restricted once more, collectors and researchers were able to continue making discoveries on Beijing’s flea markets until shortly before the pandemic. The same was true in dozens of Chinese metropolises, where collectors’ markets sprang up everywhere, from Shanghai (上海城隍庙古玩市场), via Chengdu (成都送仙桥古玩艺术城), Wuhan (武汉文物市场) to Xi’an (西安古玩城) and Dalian (大连古文化市场).

Beijing’s Panjiayuan Market was allowed to call itself one of the ten largest cultural markets in the country as early as 2004, hosting up to 4000 traders. On weekends, up to 100,000 visitors came, including thousands of foreign tourists. The flea market became a trademark of the capital, just like the Great Wall or the Peking duck.

Like all antique markets, the Panjiayuan was brought to the “brink of collapse” by Covid. The effects of the economic slowdown in China, the consequences of the trade war, and the new epidemic that led to the standstill in tourism hit the market threefold.

Sellers sought ways out of their misery online. In November 2020, the “Panjiayuan Douyin E-Commerce Livestream Base” (潘家园电商直播基地), a state-owned cultural enterprise, was formed to build a new trading center for cultural goods. Panjiayuan’s antique dealers moved into small salesrooms online. From there, they market their goods via live stream, supported by Douyin, the Chinese parent of TikTok. The state-owned cultural agency woos customers with its “one-stop service,” offering them quality control, authenticity testing, packaging to logistics. As of early 2022, 561 Panjiayuan merchants registered their businesses. By the end of October, it was 1,060 traders who are allowed to sell 30 types of “approved cultural goods” – including jade articles, jewels, pearls, and mahogany wood. This has little to do with a flea market. Contemporary history is also no longer included. The party will be pleased.

Sun Weidong, Chinese ambassador to India for the past three years, becomes the new Vice Foreign Minister of the People’s Republic.

Philipp Ludwig has moved from Dillingen China back to Dillingen in Saarland. He is now Head of the Sales Department for power transmission and processing.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not send a note for our staff section to heads@table.media!

Aesthetic, but unfortunately illegible: In Anyang, a museum visitor tries to decipher ancient seal characters. The city in Henan Province is famous for spectacular finds of oracle bones, which are considered the first evidence of Chinese writing in the Shang Dynasty (ca. 1,600-1,046 BC). Anyang has become an important archaeological site and the location of the National Museum of Chinese Writing. This week a new section of the museum opened.

Sometimes it is just wishful thinking. The wish, which is certainly particularly widespread in the Western world at the moment, is to find a mediator who will bring the warmonger Putin to his senses. And the derived thought is that Xi Jinping could be this mediator.

Since the start of the Ukraine war, speculation arises at the slightest hint that China might change its stance on Russia and move away from its partner Russia. During Scholz’s visit to Beijing, for example, Xi’s statement on the use of nuclear weapons was seen as such a hint. At the G20 summit, what had been dreamed of seemed to be confirmed: The joint final declaration condemned Russia’s actions.

But those who followed the G20 closely caught conflicting signals. Foreign Minister Wang Yi assured his Russian counterpart Sergey Lavrov that cooperation will go even further in the future. He titled the Russian war of aggression merely an “Ukraine issue.” Fabian Kretschmer analyzes China’s true attitude toward Russia.

There is also a truth behind the truth in the architecture of the Chinese state. The executive power in China – as in other countries – theoretically lies with the state organs. Xi Jinping, however, has gradually shifted all important tasks specifically to the party. A network of party commissions and working groups forms a parallel structure to state institutions and exerts significant influence, reports Christiane Kuehl. Merics researcher Nis Gruenberg gets to the bottom of the system in a new study.

A visit to the flea market can be like a treasure hunt. Maybe a long-desired record or an unrecognized designer lamp is found that makes the heart sign with joy. Until recently, Chinese flea market visitors could even stumble across politically explosive finds: rare contemporary historical documents. Photos of the Tiananmen massacre, for example, writings critical of the regime, or political flyers from the 1950s. Some of the collectibles were sold to flea market traders by the Chinese authorities themselves, reports Johnny Erling – a treasure hunter of exciting stories.

The 20th Party Congress in October cemented state and party leader Xi Jinping’s status as the absolute center of power. For ten years, Xi has been concentrating the control of politics in his hands behind the scenes of the party. To this end, starting in 2012, he established a network of so-called Leading Small Groups (LSG/领导小组) and Central Commissions (中央委员会) in the Communist Party for a wide range of policy areas, such as the economy, the environment or innovation. For most of them, Xi also made himself head.

In theory, executive power and legislation in China also lie with the power of the state organs – the State Council, ministries, and the National People’s Congress. But Xi specifically brought these functions into the party with the help of the new commissions. Today, the CP has a parallel structure to state institutions. LSGs are ad hoc bodies that are supposed to coordinate limited tasks across administrative boundaries. Central commissions, on the other hand, function as permanent political supra-ministries, as Merics experts Nis Gruenberg and Vincent Brussee analyze in a recent study. This system could indeed accelerate and better coordinate some measures, the two researchers write. But it does so at the expense of “transparency, accountability and flexibility.”

A special role in this system is played by the Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform/CCDR/中央全面深化改革委员会, through which Xi aims to accelerate structural reforms. “The CCDR is a little more special than the other commissions in the CP. It meets more often, is more involved in decision-making processes, and has firm access to bureaucratic support from party headquarters,” says study author Gruenberg. It is attached to the party’s central think tank, the Central Policy Research Office (中共中央政策研究室), which is responsible for researching and writing important documents and speeches and is based in the “General Office,” the party’s nerve center (中国共产党中央委员会办公厅, 中办 for short). So the way to the boss is short.

The CCDR was initially founded at the end of 2013 as a small leadership group, i.e. an LSG, and upgraded to a commission in 2018. In parallel, the party transformed other LSGs into commissions at that time, such as those for Finance and Economy, National Security, Foreign Affairs, and Cybersecurity and Digitalization. The goal: to “strengthen the role of the CCP’s central bodies in policy-making and coordination.” With the commissions, Xi reversed the decoupling of state administration and the party that was advanced under Deng Xiaoping, Gruenberg says. “The organization of the party and the administration are now tightly intertwined. While the State Council is responsible for implementation, policy design is now in the hands of party commissions.”

The fact that Xi demonstrably chairs at least ten commissions and LSGs himself gives their decisions greater urgency, the researcher says. “Xi sits in all the meetings of these bodies.” In this regard, he says, the CCDR is Xi’s personal reform catalyst, because with its help he can push through his priorities more quickly. “The CCDR is thus effectively a reform ministry of the CCP.” Reform, that doesn’t sound much like Xi Jinping. But the word ultimately means only a change in previous structures – not automatically a liberalization.

The CCDR is organized into six subgroups to coordinate with relevant ministries:

One of the CCDR’s goals has been to coordinate state institutions that sometimes compete with each other, Gruenberg says. “Xi was upset in 2012 about the reform backlog in Hu Jintao’s government. He wanted to break that up, so he set up all these commissions.” Today, there are thousands of representations of these commissions and LSGs at all administrative levels and in all state-owned enterprises, down to local governments.

But how do these intransparent CP groups function on a day-to-day basis? According to Gruenberg, finding details about the CCDR’s activities is like detective work since there are only a few publicly accessible documents about them. Basically, however, the process is always similar. Each year, the CCDR sets out the main reform priorities in its annual work plans (工作要点). Then it assigns, for example, a ministry to prepare specific plans or legislation for a particular agenda item. This goes back to the CCDR for approval – which then either makes further recommendations in a kind of “feedback loop,” or publishes the plan in a document. This is special because “these documents are then immediately considered ‘enacted law.’ They are binding even though they haven’t even gone through the state’s legislative process yet,” Gruenberg says.

Xi presents himself as a micromanager of everyday politics. One example of the issues: At its meeting on September 8, the CCDR, chaired by Xi, discussed and adopted five documents:

One of the CCDR’s main focuses is environmental policy. “The structural change to a circular economy is an important priority for Xi,” says Gruenberg. For example, the CCDR adopted an ‘opinion’ (意见) on the key points of waste separation, kicking off the relevant regulatory process.

According to Gruenberg, it was also the CCDR that decided China’s import ban on plastic waste. The state only formally adopted the ban afterward. The CCDR also played a leading role in setting up China’s system of national parks, according to Gruenberg. For this, “we found clear references to the flow of feedback between ministries and the CCDR.”

Special committees with specific ad hoc tasks, such as the organization of the Olympic Games, can certainly ensure efficiency. Problems arise when these structures become permanently entrenched, says Gruenberg – in other words, when the LSGs in China become central commissions and more and more power is concentrated in the direction of the party leadership: “As a result, we now have the situation that Xi has to take responsibility for everything himself. Today, you have to assume that something will only happen if it is initiated from above.”

Gruenberg expects the system to continue, even if Xi no longer has to fear any rivals in the government from March 2023 at the latest: Premier Li Keqiang, who Xi dislikes, is then expected to be replaced by his loyalist Li Qiang. The CCDR may continue to be a driver of administrative reform. “But at the same time, it sucks resources out of the agencies, all of which have put a lot of energy into Xi’s priority policies,” Gruenberg says.

Xi dominates the bureaucracy by cramming the system full of instructions. “In addition, prioritizing central requirements inevitably leads to prescribing solutions that are less adapted to local conditions than if they were worked out locally,” the expert said. “In highly heterogeneous China, this is a problem.”

For the West, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has long been persona non grata, but his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi greeted him with a handshake and a warm smile at the G20 summit in Bali on Tuesday. A look at the pictures after the fact counters the perception that emerged from the joint final declaration, which criticized Russia and was also supported by China.

What the two said to each other was probably felt bitterly by European politicians. Wang Yi pledged to “deepen pragmatic cooperation with Russia” and promote a “multipolar” world order. The Russian war of aggression was simply dubbed the “Ukraine issue.” The two sides sounded exactly like in state media reports at their previous meeting in September.

Only one of Wang’s statements can be interpreted – with a lot of goodwill – as a slight deviation from the usual line: China positively registered that Russia recently confirmed its “rational and responsible attitude” that nuclear war should never be waged.

Since February, the political West has been paying attention to every syllable that Chinese government representatives address to Russia. Most recently, they were thrilled by supposed commitments that Head of State Xi Jinping made to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz. China will “reject the use and threat of nuclear weapons” – back home, Scholz sold it as a powerful new concession.

After all, these were the most critical words from Beijing to the Kremlin since the beginning of the war. But the perception in many Western media that the Chinese leadership has finally come to its senses and moved away from Moscow is an overreaction. The nuclear statement simply reiterated an established guiding principle of Chinese policy.

So far, there are no real signs that China is changing course. Xi Jinping’s statement was not even remotely indicative of this: the statement was vague and Russia was not even mentioned directly. And during Xi’s G20 summit meetings with US President Joe Biden and French President Emmanuel Macron in Bali, the rejection of nuclear weapons was not repeated by the Chinese.

One thing is certain: The People’s Republic continues to walk a delicate tightrope. To the outside world, it presents itself as a neutral peacekeeping nation committed to negotiations and talks. In reality, however, it has taken Russia’s side. While Xi promised Vladimir Putin “boundless friendship,” he has not even spoken to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Selensky on the phone since the war began.

Moreover, the official state media continue to adopt Russian propaganda – with minimal changes. The People’s Daily newspaper, for example, says that the “nuclear threat theory is being played up in the West” and that Russia would only use its nuclear weapons for self-defense. CCTV evening news Xinwen Lianbo recently even identified Ukraine directly as the main culprit for the missile strike in Poland. And behind all the developments is an aggressive NATO under Washington’s leadership.

When the United Nations voted on a resolution to “provide a basis for future reparations payments from Russia to Ukraine” this week, China – along with Syria, North Korea, and Iran – voted against it. India, which has also been criticized by the West for its pro-Russia stance, on the other hand, abstained from the vote.

Of course, China’s relationship with Russia is not set in stone but adapts to the situation. In the case of a G20 final declaration, it does not like to be made an outsider. But the range is otherwise rather narrow: Beijing’s strategic interest in reshaping the world order according to its ideas continues to prevail over short-term disgruntlement. And to break through Western hegemony, led by the United States, Chinese logic says that Russia is absolutely necessary as an international partner.

That the use of nuclear weapons is a red line even for the Sino-Russian alliance of convenience remains true; it would hardly benefit the planned transformation of the global order. But such a stance should be a matter of course – and does not deserve international applause. Fabian Kretschmer

Nov. 21, 2022, 08:30 p.m. (Nov. 22, 2022, 3:30 a.m. Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, book launch and discussion: Overreach: How China Derailed its Peaceful Rise More

Nov. 22, 2022, 1:30 a.m. (8:30 a.m. Beijing time)

Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Webinar: Performing the Ecological Fix Under State Entrepreneurialism in China More

Nov. 22, 2022, 03:30 p.m. (10:30 p.m. Beijing time)

Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Webinar: Sarah Mellors Rodriguez – Birth Control and Abortion in China More

Nov. 22, 2022, 8:30 a.m. (03:30 p.m. Beijing time)

China Network Baden-Württemberg, Business Talk: Lockdown as a continuous loop – experience and learning process More

Nov. 23, 2022, 9 a.m. (4 p.m. Beijing time)

Dezan Shira & Associates, Webinar: Global Supply Chain Disruptions and Transfer Pricing: What to Know for Your China Operations More

Nov. 24, 2022 11 a.m. (6 p.m. Beijing time)

Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Global China Conversations: Expats leaving China: What are the consequences for multinationals and China’s economy? More

Nov. 25, 2022, 12 p.m. (7 p.m. Beijing time)

Confucius Institute FU Berlin, Lecture: Influence of the Ukraine War on International Relations More

The Chinese government has sharply criticized a draft of a new China strategy from the Foreign Ministry published on Wednesday. In response to a question from Deutsche Presse-Agentur in Beijing, a statement from the Chinese Foreign Ministry said that the classification of China as a “competitor” and “systemic rival” was a “legacy of Cold War thinking.” The Chinese side called the paper a “denigration of China by the German side.” It said the paper was full of “lies and rumors.”

The first confidential draft of the China strategy had been reported by Der Spiegel on Wednesday. The paper defines China as a partner, competitor, and systemic rival. If Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock has her way, human rights in particular are to play a greater role in dealings with China, and relations with Taiwan are to be expanded. In addition, economic dependencies are to be reduced “quickly and at a cost that is acceptable to the German economy.”

However, the new China strategy is still in the process of being coordinated with the other ministries, especially the Chancellor’s Office. The European security strategy is to be presented first before final adoption. flee

Great Britain wants to stop the takeover of the chip manufacturer Newport Wafer Fab by the Chinese group Nexperia after all. Nexperia is a Dutch subsidiary of the Chinese Wingtech Group. The British government had actually approved the controversial sale of the Welsh semiconductor factory in spring 2022 after a safety review (China.Table reported). Nexperia had already bought the graphene manufacturer in 2021.

Now, according to government sources, Trade Minister Grant Shapps vetoed the takeover of the UK’s largest chipmaker. Shapps said while foreign trade and investment, which promote growth and employment, would be welcomed: “Where we identify a risk to national security, we will act decisively.” Nexperia would thus have to resell at least 86 percent of its UK chip plant, Newport Wafer Fab, to avert “potential threats,” he said. The decision was based on a “comprehensive national security assessment,” he said.

According to the Reuters news agency, a senior Nexperia executive said they did not accept the concerns raised. He said they had not been raised in two previous reviews. “We are honestly shocked. The decision is wrong,” it said. Nexperia will take action against the decision. The British case is reminiscent of Elmos: the German government had recently prohibited the Dortmund chipmaker from selling its planned wafer production to the subsidiary of a Chinese company (China.Table reported). ari

A visibly charged conversation between Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and China’s leader Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Bali continues to stir talk. Xi did not criticize Trudeau, the Chinese Foreign Ministry stressed Thursday. Spokeswoman Mao Ning said, Beijing supports open exchanges as long as they are on an equal footing. China hopes Canada will take steps to improve bilateral relations, she said. The conversation did indeed take place that way, Mao confirmed. She explained, “This is very normal. I don’t think it should be interpreted as Chairman Xi criticizing or accusing anyone.”

In the video circulated Wednesday, a visibly disgruntled Xi complains to Trudeau about a lack of confidentiality following a bilateral conversation (China.Table reported). Xi’s displeasure may have been owed to media reports in Canada in which, according to government sources, Trudeau raised concerns about alleged espionage and Chinese interference in Canadian elections during a meeting with Xi the previous day. However, the meeting between the two had been scheduled off the record.

It remained open whether the two politicians were aware that they were filmed or at what point. Xi firmly shakes Trudeau’s hand at the end before showing the camera a brief standard smile as he leaves and walks out of the picture. The footage led to quite a bit of speculation. What is seen in the video – namely, a Chinese politician publicly displaying discontent in a “spontaneous” manner – is very rare, Chong Ja Ian, a political science professor at the National University of Singapore, told the French news agency AFP. He said the conversation between the two men showed that Xi “does not take either Trudeau or Canada that seriously as interlocutors.” The tone of the exchange was similar to that of a “major power” addressing a smaller one, Van Jackson, a professor of international relations at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, told AFP. “Xi’s language and body posture were not at all unusual for government officials who are on less than friendly terms – in private,” Jackson said.

The intention of one of Xi’s statements, which did not make it into his interpreter’s translation, also remained unclear. Depending on the translation, it could be understood as a threat or rather as resignation. Foreign Office spokeswoman Mao stressed that Xi had not meant it as a threat. The two politicians had conducted a “normal” exchange and had merely “expressed their respective positions.” rtr/ari

The Federation of German Industries (BDI) accused the European Parliament of a lack of practical relevance in the drafting process of the EU-wide supply chain law. “The EU Parliament seems to lack a sense of proportion for the competitiveness of European companies in the crisis,” BDI President Siegfried Russwurm said on Thursday. The scope across the entire value chain is “far removed from reality,” he said. He called for a more limited scope of the legislation, which is expected to have far-reaching effects on business in China. “Mandatory legal requirements must be limited to direct suppliers. Otherwise, they cannot be implemented in daily practice,” Russwurm said.

On Thursday, the EU Parliament’s Legal Affairs Committee dealt with a draft report on the EU Supply Chain Act. Currently, the design’s details are being negotiated within the EU institutions. Lara Wolters, the European Parliament’s rapporteur responsible for the supply chain law, emphasized that the goal continues to be coverage of the entire value chain.

In addition to the scope of the legislation, the question of how companies can be held accountable – including by those directly affected in third countries – is still open. The EU supply chain law is intended to be more far-reaching than the German one. The German supply chain law comes into force at the beginning of 2023. It is still unclear by when the EU-wide legislation will be completed. ari

Acceptance of Chinese car brands is comparatively high in Germany, especially among premium customers. This is the result of a survey by management consultants Berylls. While 25 percent of potential customers would also consider a Chinese product for a luxury-class model, the figure for the general car market is only 16 percent.

The result surprises the experts because the price actually plays a lesser role in the premium segment. This may be due to the respondents’ level of information: Around half of the premium customers believe that China’s automakers will prevail internationally. Of the other respondents, only 35 percent believe this.

A survey of China.Table conducted by the research house Civey last year revealed similar figures. Around 20 percent of respondents could imagine buying a Chinese car brand. 45 percent believed that Chinese manufacturers could gain a foothold in Germany. fin

China’s ideologues determine and direct what their citizens are allowed to know and think about the history of the People’s Republic. Since taking office, party leader Xi Jinping has scaled back the critical examination of the past that had been tolerated for three decades and condemned it as historical nihilism. School textbooks have been rewritten, media and the Internet, art, culture, and research have been censored, and past events have been reinterpreted or concealed. Nevertheless, there are many Chinese who have evaded control. They have their own archives at home with evidence and sources of the real happenings in the People’s Republic. They are lovers of contemporary history.

Inadvertently, the CP helped them complete their collections. Some 15 years after Mao’s death, ministries, courts, libraries, publishing houses, and even security agencies began to sell off what they considered to be superfluous items stored in archives and “ideological poison cabinets.” Among them: banned books, manuscripts, documents, pamphlets. Once forbidden and hidden treasures ended up at flea markets of the big cities. These became treasure troves for historians, amateur researchers, and passionate collectors, creating a kind of involuntary Chinese coming to terms with the past.

The postcards from abroad lay in packets among other collectibles on a stand at the Beijing flea market. They were stamped in Switzerland and showed photos of a boy from Tibet. German and English inscriptions demanded: “Freedom for the world’s youngest political prisoner.”

The letters of solidarity came from international Tibet initiatives, which called on citizens in Europe to express their solidarity with the boy by sending postcards to Beijing. The addressee was the then-party leader Jiang Zemin. He never got to see the postcards. The police stored them in their archives.

They accused China of abducting seven-year-old Gedhun Choekyi Nyima in May 1995, just days after the Dalai Lama recognized him as the reincarnation of the late 10th Panchen Lama. The CP condemned his religious choice, appointing another boy as the designated Panchen Lama successor and making the true successor disappear.

The whereabouts of the now 35-year-old are considered a state secret. The replacement lama appointed by Beijing, whom Tibetan believers continue to call the “wrong boy,” is allowed to visit Tibet’s holy monasteries on religious holidays, where the monks must worship him as the 11th Panchen Lama.

Gedhun’s state kidnapping (China.Table reported) and Beijing’s role in it have always been kept quiet publicly. In 2004, I saw the cards on display at a Beijing flea market for the first time. He could get a lot more of them, said the seller, who apparently didn’t even know who the boy was, but noticed my interest. Such a card costs 20 yuan. There was a discount for ten or more. He would not say anything about where they came from. One of the ten rules for Beijing’s big flea markets, like the Panjiayuan (潘家园) or the Bao Guosi (报国寺) temple market was: “Where things come from is none of the buyers’ business” (古玩交易卖家东西来自何方与买家无关).

The postcards that suddenly appeared answered the question of what happened to the many thousands of Amnesty petitions sent annually from Europe to China’s leaders. They were not destroyed but kept by the authorities.

But when Beijing ministries, institutes, and courts planned new buildings and moved around the year 2000, they cleared out their overflowing evidence rooms and state archives. Authorities parted with useless stocks of yellowing documents by the sackful. From banned, once cultural revolutionary cartoons against Mao’s inner-party enemies, to confiscated regime-critical pamphlets. Even internally classified old party resolutions, former arrest warrants and sentences, handwritten self-criticisms, or letters of denunciation were disposed of. They should have been shredded. Clever flea market dealers with connections took advantage of rampant corruption, official disinterest, and a lack of controls and bought them from the authorities, often at the price of their paperweight.

Everything that seemed useless was apparently discarded. Among them were piles of canceled leaflets from the propaganda war between the People’s Republic and Taiwan. Starting in the late 1950s, Beijing had the Taiwanese island of Qinmen bombed and repeatedly shot with propaganda shells full of leaflets. Apparently, Beijing ministries kept the receipts. These ended up in flea markets, along with leaflets dropped on China from Taiwan. Mainland citizens loyal to the state picked them up and delivered them. I saw the leaflets lying on a stand: One called on Taiwan’s islanders to surrender, the other on China’s peasants to overthrow the Mao regime.

The offer was new and met with demand: Private flea markets, which had been banned after the founding of the People’s Republic, only slowly re-emerged after Mao’s death. At first, they offered junk and old bicycle parts, tools and sewing machines. Around 1980, the first Beijing bird and flower market appeared.

Soon, there was no stopping them. Urban society became more prosperous, controls decreased. Chinese warmed up again to their traditional hobby of collecting antiques, scroll paintings, porcelain, pearls, or jade. Antique and art markets boomed.

Aside from a passion for valuable antiques, which more often turned out to be fake, enthusiasts began to take an interest in objects from their own contemporary history for the first time. They collected everything, from Mao writings and devotional objects, posters and buttons, art and kitsch from the Cultural Revolution, and China’s rationing system, to private diaries and family letters.

Old photos were also in demand. I once found photographs of Mao receiving German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and his wife Loki at his Zhongnanhai residence on October 30, 1975. The original prints had apparently been discarded because the German guest of honor was waiting with Mrs. Loki on a bench in the anteroom while Mao stood and just greeted the German ambassador at the time, Rolf Friedemann Pauls, who accompanied Schmidt. When I met Helmut Schmidt later in Beijing, I gave him one of the photos as a gift.

Some collectors specialized on the impact of Mao’s political campaigns on China, from land reform, the Great Leap Forward, to the Cultural Revolution. They found new documents in flea markets about famines, never-reported natural disasters and floods, and brutal persecution. Or Red Guard newspapers that condemned, for example, Xi Zhongxun, Xi Jinping’s father. Even internal documents and photos about the Tiananmen massacre of June 4, 1989, were on offer.

The party lost control of its narrative on history. Flea markets thus became, overnight, the only places in China that openly revealed political secrets and also provided evidence to back them up. For Beijing, it was a legal gray area.

While museums dedicated to the history of the Cultural Revolution had to close again, and the Foreign Ministry had access to its once-open historical archives restricted once more, collectors and researchers were able to continue making discoveries on Beijing’s flea markets until shortly before the pandemic. The same was true in dozens of Chinese metropolises, where collectors’ markets sprang up everywhere, from Shanghai (上海城隍庙古玩市场), via Chengdu (成都送仙桥古玩艺术城), Wuhan (武汉文物市场) to Xi’an (西安古玩城) and Dalian (大连古文化市场).

Beijing’s Panjiayuan Market was allowed to call itself one of the ten largest cultural markets in the country as early as 2004, hosting up to 4000 traders. On weekends, up to 100,000 visitors came, including thousands of foreign tourists. The flea market became a trademark of the capital, just like the Great Wall or the Peking duck.

Like all antique markets, the Panjiayuan was brought to the “brink of collapse” by Covid. The effects of the economic slowdown in China, the consequences of the trade war, and the new epidemic that led to the standstill in tourism hit the market threefold.

Sellers sought ways out of their misery online. In November 2020, the “Panjiayuan Douyin E-Commerce Livestream Base” (潘家园电商直播基地), a state-owned cultural enterprise, was formed to build a new trading center for cultural goods. Panjiayuan’s antique dealers moved into small salesrooms online. From there, they market their goods via live stream, supported by Douyin, the Chinese parent of TikTok. The state-owned cultural agency woos customers with its “one-stop service,” offering them quality control, authenticity testing, packaging to logistics. As of early 2022, 561 Panjiayuan merchants registered their businesses. By the end of October, it was 1,060 traders who are allowed to sell 30 types of “approved cultural goods” – including jade articles, jewels, pearls, and mahogany wood. This has little to do with a flea market. Contemporary history is also no longer included. The party will be pleased.

Sun Weidong, Chinese ambassador to India for the past three years, becomes the new Vice Foreign Minister of the People’s Republic.

Philipp Ludwig has moved from Dillingen China back to Dillingen in Saarland. He is now Head of the Sales Department for power transmission and processing.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not send a note for our staff section to heads@table.media!

Aesthetic, but unfortunately illegible: In Anyang, a museum visitor tries to decipher ancient seal characters. The city in Henan Province is famous for spectacular finds of oracle bones, which are considered the first evidence of Chinese writing in the Shang Dynasty (ca. 1,600-1,046 BC). Anyang has become an important archaeological site and the location of the National Museum of Chinese Writing. This week a new section of the museum opened.