The statistics office in Beijing published the latest economic figures on Monday: the year 2021 achieved a plus of 8.1 percent. That sounds impressive and even exceeds the targets set by the government in Beijing. However, Finn Mayer-Kuckuk took a closer look at the data and found: Be it in the real estate sector, infrastructure, or the automotive market – China’s economy is under pressure from multiple fronts. Thus, cutting its key interest rate at the beginning of the week was a wise decision by the Chinese central bank.

China is the world’s leading exporter. That is no secret, especially in Germany, which had lost this title to the People’s Republic. What is far less known, however, is the fact that China is also heavily dependent on imports. Christiane Kuehl analyzes how strongly China depends on preliminary technical products and raw materials. For example, China covers about 80 percent of its demand for soybeans, iron ore, copper, and bauxite from abroad. And no other country in the world imports this many semiconductors. This is a thorn in the side of the government in Beijing. It has long been looking hard to find ways to rid itself of this dependence.

So far, recycling in China has been a business model for the lower class. For a few yuan, traders buy paper, empty plastic bottles, and other garbage from consumers and bring it on their cargo bikes to recycling plants outside the city at the end of each day. But that is about to change. Delivery services in particular are to contribute more to environmental protection. Beijing wants 90 percent of delivered packages to be made from environmentally certified packaging materials. Ning Wang has taken a close look at what the delivery industry has been up to in terms of recycling. The result: Business is booming, but environmental protection is not exactly a top priority.

I hope you enjoy reading today’s issue!

China’s growth has once again exceeded its own targets. Economic output rose by 8.1 percent in 2021. This was announced by the National Bureau of Statistics in Beijing on Monday. Premier Li Keqiang had announced “over six percent” last March. With slow real estate growth and a protracted pandemic, analysts expect a much lower figure for the current year. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences expects 5.5 percent for 2022. The Chinese central bank shares this assessment.

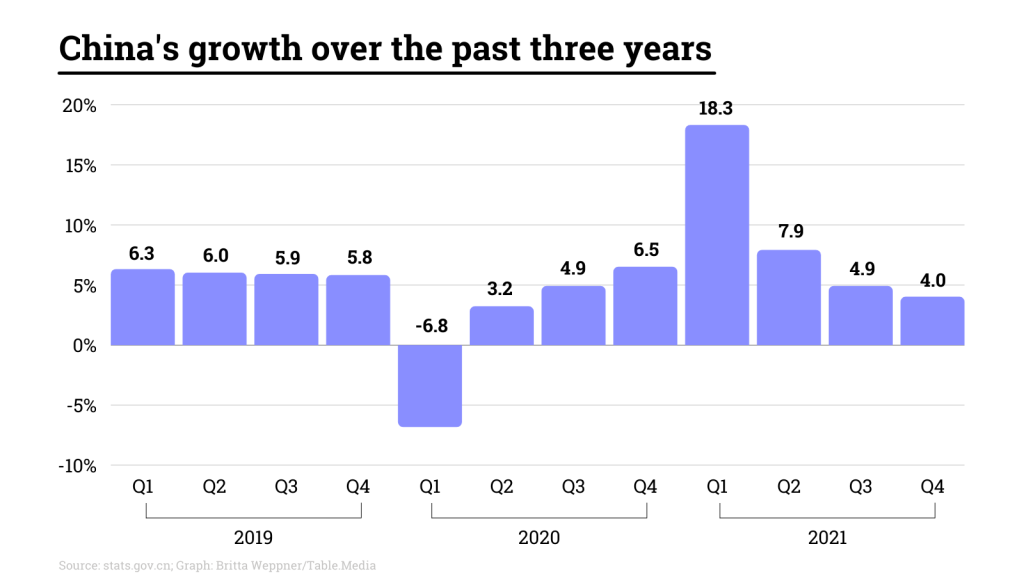

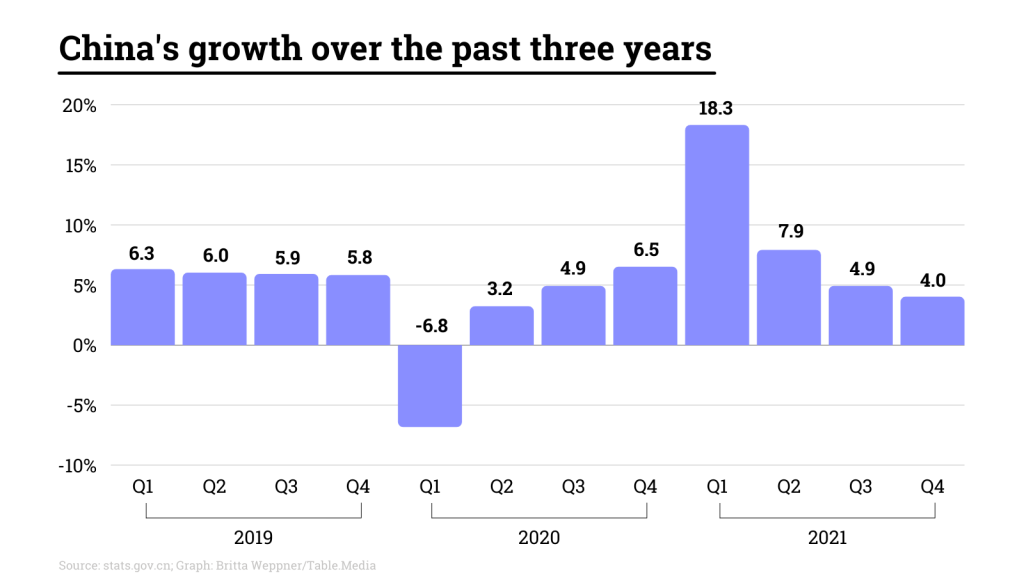

Another reason for lower growth expectations lies in the statistics themselves. Last year’s high value was influenced by the Covid slump two years ago. The distribution over the year therefore also showed a sharply declining curve. At the beginning of the year, there was an initial post-Covid effect with a growth of 18.3 percent. The last quarter of the year then only saw growth of just under four percent.

The growth figures for the first months of 2021 relate precisely to the horror quarter of the first Covid outbreak at the beginning of 2020. By contrast, the economic data towards the end of the year had then again to be compared to a healthy situation. This also applies to the first quarter of the current year. So the markets will have to get used to low single-digit figures again.

For the analysts at Nomura bank, the Covid risks are currently the main focus. By the end of the Winter Olympics in China (February 4-20), even individual positive test results will lead to large-scale lockdowns. These, in turn, will hit economic activity. “As was the case last year, many people will also be unable to return to their hometowns for Chinese New Year,” Nomura economists Lu Ting and Wang Jing expect. That will curb consumption and tourism revenues.

These bleak short-term economic forecasts are also the reason behind the central bank’s actions on Monday. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) cut two key interest rates. In light of the newly reported turbo growth of over eight percent, this seems paradoxical at first. But the PBoC intends to support growth before it collapses. To this end, it is pumping more money into the economy.

Experts therefore expect monetary policy to remain at ease during the year. The Nomura analysts even expect another potential interest rate cut in the first half of the year. A reduction in the minimum reserve ratio is also possible, they say. This would give banks more room to lend.

In parallel, the PBoC could also buy currencies such as euros and dollars on the foreign exchange market. In this way, it would depress the exchange rate of the yuan. The return of Covid through global Omicron outbreaks will weigh on trade, the analysts believe. A lower Yuan exchange rate could support exports.

At the same time, government spending on infrastructure is expected to increase. When private real estate companies run out of money (China.Table reported), the state has to step in and provide new construction projects. And right now, the indicators in the real estate sector look pretty bleak. Investment dropped by 13.9 percent year-on-year in December. Sales of new apartments and houses dropped by 17.8 and 15.6 percent in November and December, respectively. The indicator for new home construction projects even plunged 31.1 percent. Real estate companies have simply run out of money.

The other important pillars of the economy are also weakening. The retail sector recorded growth of just 1.7 percent in December. Since inflation was 2.2 percent at the same time, sales even declined on a price-adjusted basis. Things didn’t look much better for the auto market, either. Sales dropped by 7.4 percent in December, having already declined by 9 percent in November. Unlike unit sales figures, these values represent the total value of goods sold.

This paints a picture of an economy under pressure from two sides. The pandemic is dragging on longer than hoped. At the same time, long-term effects are at play: The lapse on the real estate market is the payback for a credit-driven boom. In addition, overall growth in China is in decline. The bigger an economy becomes, the less likely high percentage growth is to be expected.

Meanwhile, the government remains as capable of acting as ever. And since the country is currently caught in a zero-covid trap with insufficient basic immunity (China.Table reported), an end to lockdowns would be all the more liberating and spectacular. Opening up to international business travelers would also have an extremely revitalizing effect. However, it currently seems unlikely that this will happen in 2022.

When we think of import dependency, one very specific resource comes to mind: crude oil. The People’s Republic of China has been the world’s largest oil importer since 2017. And the gap between a stagnating domestic production volume and the ever-growing demand is widening. As if that were not enough, oil is not the only resource of which China has too little. Aside from fragile power security, there are other vulnerabilities.

China will need to establish a “strategic baseline” to ensure self-sufficiency in key raw materials, from power to soybeans, President Xi Jinping stressed in December at the Communist Party’s annual economic conference. “For a big country like us, ensuring the supply of primary products is a significant strategic problem,” Xi told the delegates. “Soybeans, iron ore, crude oil, natural gas, copper and aluminum ore… all these are connected to the fate of our nation.”

In 2021, China’s imports grew by 21.5 percent to ¥17.37 trillion (€2.4 trillion). Most recently, growth has been driven primarily by rising demand for raw materials for the energy sector as well as metals. Concepts such as the dual circulation presented by Xi in 2020 are therefore intended to strengthen the role of the domestic market. The 14th Five-Year Plan, for example, targets Chinese technological independence by 2025. But at least in the short term, China needs imports.

The issue is accordingly gaining priority on China’s long-term agenda under Xi. For commodities such as soybeans, iron ore, crude oil, natural gas, copper, bauxite, and gold, up to 80 percent of China’s consumption is covered by imports. In the technology sector, China’s main imports are semiconductors: It is the world’s largest chip importer since 2005. But China also has to source other technologies and components largely from foreign countries. According to a newly published study by the Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CEST) at Georgetown University in the United States, these include LIDAR systems for self-driving cars, engine casings for commercial aircraft, and reagents for gene editing kits.

Geopolitical tensions between China and the West, especially with the US, have long had an impact on the country’s imports. In 2018, US soybean exports to China were caught in the maelstrom of the trade war. Growing Chinese meat consumption has been driving huge increases in demand for corn and soybeans as animal feed. In the past 20 years, soybean imports have increased tenfold, from 10.4 million to 100.3 million tons. Here, too, the People’s Republic is the world leader by a wide margin.

As a result of the trade conflict with Washington, Chinese imports of US soybeans halved from 32.9 billion tons in 2017 to just 16.6 million tons in 2018, and China turned to Brazil to fill the gap. Today, Brazil supplies 60 percent of the country’s soybean imports. Thirty percent are still imported from the United States. But Brazil’s production can no longer keep up with China’s demand. Beijing is therefore trying to establish more channels in Russia and Southeast Asia. Especially since the demand for imports will increase even further since Brazil’s croplands are shrinking by a whopping 14.8 percent in 2021. According to the National Statistics Office, many farmers are giving up soybean cultivation due to low margins.

Also, former President Donald Trump’s US blacklist policy has been cutting off many Chinese companies from important components for years. In 2018 Trump began putting hundreds of Chinese companies on the Department of Commerce‘s innocuous-sounding Entity List. This was equivalent to banning US companies from selling to these Chinese companies. The Biden administration held on to that list. In December, it even added more companies, including AI specialist SenseTime and leading drone manufacturer DJI.

China also benefited from foreign technology transfer in earlier years. But US tech investment plummeted by 96 percent since 2016, according to CEST: “To compensate for declining investment, Beijing has increasingly turned to shell companies and intermediary agents to source foreign components, reagents, and associated manufacturing equipment.” While less than 10 percent of the Chinese military’s equipment suppliers are on US export control and sanctions lists, experts said, “some make a business out of repackaging and reselling US-origin equipment to sanctioned Chinese military units.” This gray area may help China in the short term, but this trick does not reduce its dependence on foreign countries.

China relies on imports for 35 key technologies that it cannot produce domestically in adequate quality or quantity, CEST researcher Emily Weinstein wrote in early January, citing China’s Ministry of Education. “These technologies include heavy-duty gas turbines, high-pressure piston pumps, steel for high-end bearings, photolithography machines, core industrial software, and more”. In other words, an entire high-tech arsenal that an economic power needs to be able to claim a leading role in the world in the long run.

In these times of global chip shortages, Beijing is also wrestling with the EU and the US over semiconductor supplies from Taiwanese global market leader TSMC. In 2020, China imported $350 billion worth of semiconductors – more than its crude oil import volume. According to the trade magazine Technode, China recorded a trade deficit of $233.4 billion for semiconductors in 2020. For crude oil, it was “only” $185.6 billion. Despite the deficit, the People’s Republic recorded a trade surplus of around $590 billion across all commodity groups in 2020, and in 2021 the surplus even climbed to $676 billion. Incidentally, 60 percent of imported semiconductors in 2020 were components for China’s export products such as tablets and other electronic goods.

After Washington placed China’s industry leader, Shenzhen-based SMIC, on its 2020 Entity List, the company struggled to make advanced 7-nanometer chips. “SMIC lacks the machine tools to make them,” researcher Weinstein wrote. US export controls had crippled Huawei’s chip subsidiary HiSilicon. That is part of the reason China plans the domestic production of 70 percent of the chips needed for its tech and auto sector in 2025. But the target is vaguely formulated; and even then, it will still have to source many of the countless preliminary products from abroad.

Despite all the measures to strengthen China’s position as a science and technology hub, the Communist Party is struggling to build domestic supply chains for key raw materials such as semiconductors and gas turbines, Weinstein writes. China will likely remain reliant on foreign equipment well into the 2020s, he adds. Moreover, China’s path to foreign technology leads primarily through US allies such as Australia, Japan, South Korea, and the United Kingdom.

China also has to buy raw materials from geopolitical rivals – such as natural gas for the winter (China.Table reported). Meanwhile, China buys 60 percent of its iron ore from Australia. Beijing’s relations with Canberra are currently at rock bottom. China has been pestering Australia with punitive tariffs or import bans on beef, lobster, barley, and wine, for example, since Canberra called for an independent investigation into the origins of COVID-19. Australia has since joined several security alliances implicitly aimed at China. Recently, it signed a partnership with Japan (China.Table reported).

So far, Beijing has not dared to touch iron ore imports from Down Under. But China is not pleased with its dependence on Australian ore. The People’s Republic is therefore searching for alternatives. In 2020, it found one in the Simandou hill range in the West African country of Guinea. It is said to have the world’s largest deposit of undeveloped high-quality iron ore. In addition to developing the mine, 650 kilometers of railroad and a modern ore port have to be built. In 2020, China secured two of four sections of the planned mine as part of a consortium with French and Singaporean companies.

But Guinea is politically unstable. In September 2021, a military coup overthrew President Alpha Conde. Since then, the coup leader, Colonel Mamady Doumbouya has been in power. Beijing criticized the coup – which is unusual for China. After all, no one knows whether the army will now acknowledge the mining treaty. But China is already dependent on Guinea: The country supplies the Chinese with 55 percent of its bauxite demand for its aluminum industry.

While China’s package delivery services used to pride themselves on constantly surpassing each other in the number of shipped deliveries, a new trend has now emerged: Who is the greenest? Suddenly, packaging sustainability has gained significant importance in the competition between the big players of the People’s Republic.

Cainiao, the logistics division of e-commerce retailer Alibaba, already began setting up large collection stations for cardboard boxes in front of residential buildings several years ago. This allows residents to dispose of the packaging of their deliveries right away so that they can be recycled. Alternatively, they can also take them back to the respective collection station. Cainiao is said to already offer more than 80,000 such collection stations nationwide.

JD.com’s logistics division and household appliance supplier Suning are focusing on “going green” in the production of their packages. Both have launched so-called green packaging programs. Alibaba, meanwhile, has announced the highly ambitious goal of reaching carbon neutrality by 2030. Together with retailers and consumers, the e-commerce giant wants to reduce its CO2 emissions by 1.5 gigatons by 2035. The e-commerce industry is responsible for around 80 percent of deliveries in the People’s Republic.

Due to increasing urbanization and a further growing middle class, the delivery business has grown immensely in recent years. In 2021, delivery services will have delivered a total of 108.5 billion packages. That’s 30 percent more packages than in 2020, despite higher energy prices, the economic impacts of pandemic measures, and recurring lockdowns.

However, the newly gained awareness of logistics companies for greater environmental protection is not as much owed to their guilty consciences about climate change. Rather, it is the result of increasingly stricter regulations from Beijing, which is why companies are now looking to make their supply chains more sustainable. For example, the State Post Bureau, together with the Ministry of Commerce and the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), announced a new law in early January to encourage package delivery services to use even more recycled packaging materials.

On January 6th, the State Post Bureau announced eco-friendly product certification for packaging used by express delivery services to “improve the quality and efficiency of the industry.” Package delivery services are to increasingly use these certified products in the future. The proportion is required to be 90 percent by the end of the year.

In addition, authorities want to standardize the processes of packaging operations and thus reduce the consumption of packaging materials such as corrugated board base paper and adhesive tapes. By the end of the year, the number of recyclable boxes is expected to rise to 10 million, and the number of recycled corrugated cardboard boxes to as much as 700 million.

But it’s not just about cardboard boxes and plastic bags. Bubble wrap, adhesive tapes, and labels are also responsible for generating more than 9 million tons of paper waste and 1.8 tons of plastic waste in China every year. This is shown by data released by the antitrust authority. Experts believe that three-quarters of packaging waste is caused by postal services.

Beijing wants to change all of that this year – and fast. In addition to mandating that the package delivery industry reduce or recycle used materials, the central government announced a two-year pilot program to encourage the use of recycled materials. Effective immediately.

For years, Beijing has been trying to get companies to recycle by issuing regulations and guidelines. So far, however, the reality looks completely different: The proportion of recycled paper has hardly changed for years. In 2020, the recycling rate of paper and cardboard in China reached 46.5 percent. In 2014, it was even higher at over 48 percent.

The fact that hardly anything has been done so far to protect the environment is likely because the logistics industry has barely been able to keep up with deliveries because of the steadily growing consumption. Instead, package delivery services had to deal with staffing and logistics problems, especially as a result of the recurring lockdowns in the country. Environmental and climate protection was a secondary concern.

A survey on behalf of two environmental protection organizations also shows how little companies have addressed recycling to date. The results were staggering: The delivery services JD Logistics and SF Express used sustainable cardboard boxes or packaging for less than 0.5 percent of all orders. And 70 percent of the companies surveyed stated that they had not used any recycling packaging to date.

Recycling in China has so far been mainly a business model for people at the lower end of society. They buy scrap metal, steel, and plastic from small businesses for a handful of yuan, above all paper from consumers. Towards the end of the day, convoys of cargo bikes take the “recyclables” to state recycling plants outside the city, where they are paid a little more than what they had previously paid the paper collectors.

Whether these new regulations will bring change is something Zhou Jiangming doubts. The project manager of Plastic Free China criticizes that the current regulations mainly affect courier companies, creating a regulatory vacuum between e-commerce retailers and delivery companies. “Solving environmental problems through courier packaging is a systematic work,” Zhou told the online magazine Sixth Tone. Focusing only on one player would not achieve results.

In any case, the logistics company Cainiao has already found its very own approach to increasing its recycling rate: For every cardboard box returned, the customer receives an egg in return.

China’s population has once again grown very slowly – by 480,000 to a population of 1.413 billion in 2021. These figures were published by the National Bureau of Statistics of China in Beijing on Monday. Officials are particularly concerned about the birth rate: According to official figures, the number of newborns fell by 11.5 percent to 10.6 million. The birth rate thus slipped to a drastic 7.5 newborns per 1,000 people. It is the lowest figure recorded in the China Statistical Yearbook since 1978 and also the lowest since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949.

The proportion of people of official working age – i.e., between 16 and 59 – also fell in 2021 from 63.3 percent to 62.5 percent of the total population. Ten years ago, it was still around 70 percent. Demographers expect that this proportion could even fall to 50 percent by 2050. At the same time, China is getting older and older: The number of citizens over 60 years grew from 18.7 percent to 18.9 percent of the total population within one year.

For decades, the Communist Party has kept a close eye on the birth rate: The one-child policy, introduced in 1980, was once intended to limit population growth. When the working-age population began to decline earlier than expected, the government began to rethink: In 2015, the one-child policy was abolished; from then on, couples were allowed to have two children. However, this only caused a slight increase in births for a short time, as current figures show. Since May 2021, couples are allowed to have up to three children.

On Monday, the statistics office cited the Covid pandemic to be one of the factors causing the renewed decline in births. Other external factors are also keeping couples from having more children: high housing costs, education and health costs, cramped living conditions, and job discrimination against mothers. Meanwhile, the government is promoting more births with tax benefits (China Table reported).

In light of fewer births, fewer employed, and a growing number of elderly citizens, experts are warning about a “demographic time bomb”. Soon, the People’s Republic might not have enough people to care for the growing number of elderly. rad

Because of rising new Covid infections, the Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (February 4-20) has halted the free sale of tickets. Considering the serious and complicated situation and for the safety of all participants and visitors, it was decided to stop selling tickets, BOCOG said Monday. The available capacity will be used to invite specific groups of viewers instead.

Those selected as spectators are also expected to strictly adhere to COVID-19 regulations before, during, and after each event. This is said to be a prerequisite for the safe and smooth holding of the Games. According to reports, the organizers have already started inviting selected spectators for the opening of the Games through authorities.

Even the athletes are not allowed to move freely and are confined to strictly separated areas instead. It’s a kind of bubble where athletes, volunteers, journalists, and officials will stay – isolated from the rest of the country. They are required to test themselves daily and are not allowed to have any contact with the outside world. This is to prevent the introduction of the Coronavirus.

Foreign spectators are not allowed to attend the Games anyway. This was already decided on in September. At the Summer Games in Tokyo last year, no visitors were allowed at all.

Meanwhile, the number of new Covid infections in China reached its highest level since March 2020 on Monday, with 223 new cases reported nationwide, including 80 in the virus-hit port city of Tianjin and an additional 9 in Guangzhou in southern China. Another 68 cases were reported in the central province of Henan, where partial lockdown measures are in place for several million residents and a massive testing campaign has been underway. The first Omicron case has been registered in Beijing over the weekend (China.Table reported). rad

China’s President Xi Jinping opened the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) online conference “Davos Agenda” on Monday. In his address, Xi called for the stabilization of the global economy and pleaded for greater international cooperation. In times of the Covid pandemic, it would be vital to preventing the global economy from suffering another slump, Xi said.

China will begin the Year of the Tiger in a few days. The tiger symbolizes courage and strength – qualities that the countries of the world should also adopt to overcome the current challenges. Xi also urged the industrialized countries not to spend less money in these times. If they were to slow down or even reverse their monetary policy, this would have negative effects on the global economy and financial stability, Xi warned. Developing countries would have to bear the brunt of such a policy. These countries have already been hit hard by the pandemic, and many have fallen back into poverty and instability.

The World Bank recently warned of a significant slowdown in the global economy. This year, the global economy is expected to grow by 4.1 percent, followed by 3.2 percent in 2023. Poorer countries, in particular, are therefore under pressure.

“Let us join hands with full confidence, and work together for a shared future,” China’s president appealed. The fight against Covid, especially, would be a matter of joining forces to put an end to the pandemic. Xi stressed the importance of vaccines and their fair distribution to close the global vaccination gap. China would continue to actively participate in international cooperation to fight the pandemic.

Other speakers on the program include UN Secretary-General António Guterres and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Germany’s Chancellor Olaf Scholz plans to attend the virtual Davos Dialogue on Wednesday.

The World Economic Forum in Davos, which traditionally takes place in mid-January, had been postponed due to the Covid situation. Instead, the foundation had announced that it would bring leaders together digitally. rad

Peng Jingtang takes up his new post with a pithy promise. As chief of the Hong Kong garrison of the People’s Liberation Army, pledges to “perform defense duties in accordance with the law, resolutely defend national sovereignty, security, and development interests, and firmly safeguard Hong Kong’s long-term prosperity and stability.”

Peng’s words may well be understood as a threat to the remaining pro-democracy forces in the city. Beijing sent a clear signal by appointing the Major General as local PLA commander, who also felt empowered to have a say in the city’s security policy. Under the Basic Law, commonly referred to as Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, Beijing has sovereignty over Hong Kong’s foreign and defense policies. Between the lines, Peng was relatively blunt in stating that the Chinese government is prepared to potentially use the military against the people of Hong Kong in the future.

Last week, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam already assured the local commander-in-chief that her government would work closely with Peng. The chances that Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protest movement will flare up again are slim to none. After all, nearly all of the opposition’s leading figures have been arrested or have fled the country. But Beijing has learned from its own experiences that authoritarian governance works primarily through deterrence. A notorious military leader with experience in the supposed fight against terror is a perfect warning signal.

Because Peng Jingtang commanded the paramilitary People’s Armed Police in Xinjiang before his assignment to Hong Kong. Since 2018, he has also been involved in the arrests of hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs. Around one million people are currently held in internment camps. Beijing defends the existence of the camps by citing, among other things, the threat of terrorism in the region. Several governments, including the US, on the other hand, have classified Beijing’s actions in Xinjiang as genocide.

That Peng’s transfer to Hong Kong is not owed to random chance but was a deliberate move is confirmed by President Xi Jinping’s signature under the appointment of the new chief. Previously, Xinjiang’s security chief had already been transferred (China.Table reported). Wang Junzheng was assigned to Tibet after nearly two years. The security situation there has also been extremely tense for years. grz

Jingwei Jia has left Swiss reinsurer Swiss Re. After 15 years with the company, and most recently six years as CEO of Greater China, Jia left the Zurich-based group at the beginning of January. His interim successor is Jonathan Rake, previously CEO for the Asia Pacific.

Elvis He is the new Head of Technology, Media and Telecom for China at Swiss bank UBS Group AG. He was previously Head of TMT at Hong Kong-based Canon Law Society of America (CLSA), a subsidiary of Shenzhen investment bank CITIC Securities, for four years.

New Chinese tennis hope: 19-year-old Zheng Qinwen celebrated her first victory in a Grand Slam tournament on Monday night. She defeated Belarusian Alyaksandra Sasnovich in three sets at the Australian Open in Melbourne. Reaching the second round earns Zheng prize money of $140,000, well over double what she has earned so far in her career. China’s tennis fans can thus hope for a new star after 35-year-old Peng Shuai had to abruptly end her career a few weeks ago following her allegations of sexual assault against a senior party cadre.

The statistics office in Beijing published the latest economic figures on Monday: the year 2021 achieved a plus of 8.1 percent. That sounds impressive and even exceeds the targets set by the government in Beijing. However, Finn Mayer-Kuckuk took a closer look at the data and found: Be it in the real estate sector, infrastructure, or the automotive market – China’s economy is under pressure from multiple fronts. Thus, cutting its key interest rate at the beginning of the week was a wise decision by the Chinese central bank.

China is the world’s leading exporter. That is no secret, especially in Germany, which had lost this title to the People’s Republic. What is far less known, however, is the fact that China is also heavily dependent on imports. Christiane Kuehl analyzes how strongly China depends on preliminary technical products and raw materials. For example, China covers about 80 percent of its demand for soybeans, iron ore, copper, and bauxite from abroad. And no other country in the world imports this many semiconductors. This is a thorn in the side of the government in Beijing. It has long been looking hard to find ways to rid itself of this dependence.

So far, recycling in China has been a business model for the lower class. For a few yuan, traders buy paper, empty plastic bottles, and other garbage from consumers and bring it on their cargo bikes to recycling plants outside the city at the end of each day. But that is about to change. Delivery services in particular are to contribute more to environmental protection. Beijing wants 90 percent of delivered packages to be made from environmentally certified packaging materials. Ning Wang has taken a close look at what the delivery industry has been up to in terms of recycling. The result: Business is booming, but environmental protection is not exactly a top priority.

I hope you enjoy reading today’s issue!

China’s growth has once again exceeded its own targets. Economic output rose by 8.1 percent in 2021. This was announced by the National Bureau of Statistics in Beijing on Monday. Premier Li Keqiang had announced “over six percent” last March. With slow real estate growth and a protracted pandemic, analysts expect a much lower figure for the current year. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences expects 5.5 percent for 2022. The Chinese central bank shares this assessment.

Another reason for lower growth expectations lies in the statistics themselves. Last year’s high value was influenced by the Covid slump two years ago. The distribution over the year therefore also showed a sharply declining curve. At the beginning of the year, there was an initial post-Covid effect with a growth of 18.3 percent. The last quarter of the year then only saw growth of just under four percent.

The growth figures for the first months of 2021 relate precisely to the horror quarter of the first Covid outbreak at the beginning of 2020. By contrast, the economic data towards the end of the year had then again to be compared to a healthy situation. This also applies to the first quarter of the current year. So the markets will have to get used to low single-digit figures again.

For the analysts at Nomura bank, the Covid risks are currently the main focus. By the end of the Winter Olympics in China (February 4-20), even individual positive test results will lead to large-scale lockdowns. These, in turn, will hit economic activity. “As was the case last year, many people will also be unable to return to their hometowns for Chinese New Year,” Nomura economists Lu Ting and Wang Jing expect. That will curb consumption and tourism revenues.

These bleak short-term economic forecasts are also the reason behind the central bank’s actions on Monday. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) cut two key interest rates. In light of the newly reported turbo growth of over eight percent, this seems paradoxical at first. But the PBoC intends to support growth before it collapses. To this end, it is pumping more money into the economy.

Experts therefore expect monetary policy to remain at ease during the year. The Nomura analysts even expect another potential interest rate cut in the first half of the year. A reduction in the minimum reserve ratio is also possible, they say. This would give banks more room to lend.

In parallel, the PBoC could also buy currencies such as euros and dollars on the foreign exchange market. In this way, it would depress the exchange rate of the yuan. The return of Covid through global Omicron outbreaks will weigh on trade, the analysts believe. A lower Yuan exchange rate could support exports.

At the same time, government spending on infrastructure is expected to increase. When private real estate companies run out of money (China.Table reported), the state has to step in and provide new construction projects. And right now, the indicators in the real estate sector look pretty bleak. Investment dropped by 13.9 percent year-on-year in December. Sales of new apartments and houses dropped by 17.8 and 15.6 percent in November and December, respectively. The indicator for new home construction projects even plunged 31.1 percent. Real estate companies have simply run out of money.

The other important pillars of the economy are also weakening. The retail sector recorded growth of just 1.7 percent in December. Since inflation was 2.2 percent at the same time, sales even declined on a price-adjusted basis. Things didn’t look much better for the auto market, either. Sales dropped by 7.4 percent in December, having already declined by 9 percent in November. Unlike unit sales figures, these values represent the total value of goods sold.

This paints a picture of an economy under pressure from two sides. The pandemic is dragging on longer than hoped. At the same time, long-term effects are at play: The lapse on the real estate market is the payback for a credit-driven boom. In addition, overall growth in China is in decline. The bigger an economy becomes, the less likely high percentage growth is to be expected.

Meanwhile, the government remains as capable of acting as ever. And since the country is currently caught in a zero-covid trap with insufficient basic immunity (China.Table reported), an end to lockdowns would be all the more liberating and spectacular. Opening up to international business travelers would also have an extremely revitalizing effect. However, it currently seems unlikely that this will happen in 2022.

When we think of import dependency, one very specific resource comes to mind: crude oil. The People’s Republic of China has been the world’s largest oil importer since 2017. And the gap between a stagnating domestic production volume and the ever-growing demand is widening. As if that were not enough, oil is not the only resource of which China has too little. Aside from fragile power security, there are other vulnerabilities.

China will need to establish a “strategic baseline” to ensure self-sufficiency in key raw materials, from power to soybeans, President Xi Jinping stressed in December at the Communist Party’s annual economic conference. “For a big country like us, ensuring the supply of primary products is a significant strategic problem,” Xi told the delegates. “Soybeans, iron ore, crude oil, natural gas, copper and aluminum ore… all these are connected to the fate of our nation.”

In 2021, China’s imports grew by 21.5 percent to ¥17.37 trillion (€2.4 trillion). Most recently, growth has been driven primarily by rising demand for raw materials for the energy sector as well as metals. Concepts such as the dual circulation presented by Xi in 2020 are therefore intended to strengthen the role of the domestic market. The 14th Five-Year Plan, for example, targets Chinese technological independence by 2025. But at least in the short term, China needs imports.

The issue is accordingly gaining priority on China’s long-term agenda under Xi. For commodities such as soybeans, iron ore, crude oil, natural gas, copper, bauxite, and gold, up to 80 percent of China’s consumption is covered by imports. In the technology sector, China’s main imports are semiconductors: It is the world’s largest chip importer since 2005. But China also has to source other technologies and components largely from foreign countries. According to a newly published study by the Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CEST) at Georgetown University in the United States, these include LIDAR systems for self-driving cars, engine casings for commercial aircraft, and reagents for gene editing kits.

Geopolitical tensions between China and the West, especially with the US, have long had an impact on the country’s imports. In 2018, US soybean exports to China were caught in the maelstrom of the trade war. Growing Chinese meat consumption has been driving huge increases in demand for corn and soybeans as animal feed. In the past 20 years, soybean imports have increased tenfold, from 10.4 million to 100.3 million tons. Here, too, the People’s Republic is the world leader by a wide margin.

As a result of the trade conflict with Washington, Chinese imports of US soybeans halved from 32.9 billion tons in 2017 to just 16.6 million tons in 2018, and China turned to Brazil to fill the gap. Today, Brazil supplies 60 percent of the country’s soybean imports. Thirty percent are still imported from the United States. But Brazil’s production can no longer keep up with China’s demand. Beijing is therefore trying to establish more channels in Russia and Southeast Asia. Especially since the demand for imports will increase even further since Brazil’s croplands are shrinking by a whopping 14.8 percent in 2021. According to the National Statistics Office, many farmers are giving up soybean cultivation due to low margins.

Also, former President Donald Trump’s US blacklist policy has been cutting off many Chinese companies from important components for years. In 2018 Trump began putting hundreds of Chinese companies on the Department of Commerce‘s innocuous-sounding Entity List. This was equivalent to banning US companies from selling to these Chinese companies. The Biden administration held on to that list. In December, it even added more companies, including AI specialist SenseTime and leading drone manufacturer DJI.

China also benefited from foreign technology transfer in earlier years. But US tech investment plummeted by 96 percent since 2016, according to CEST: “To compensate for declining investment, Beijing has increasingly turned to shell companies and intermediary agents to source foreign components, reagents, and associated manufacturing equipment.” While less than 10 percent of the Chinese military’s equipment suppliers are on US export control and sanctions lists, experts said, “some make a business out of repackaging and reselling US-origin equipment to sanctioned Chinese military units.” This gray area may help China in the short term, but this trick does not reduce its dependence on foreign countries.

China relies on imports for 35 key technologies that it cannot produce domestically in adequate quality or quantity, CEST researcher Emily Weinstein wrote in early January, citing China’s Ministry of Education. “These technologies include heavy-duty gas turbines, high-pressure piston pumps, steel for high-end bearings, photolithography machines, core industrial software, and more”. In other words, an entire high-tech arsenal that an economic power needs to be able to claim a leading role in the world in the long run.

In these times of global chip shortages, Beijing is also wrestling with the EU and the US over semiconductor supplies from Taiwanese global market leader TSMC. In 2020, China imported $350 billion worth of semiconductors – more than its crude oil import volume. According to the trade magazine Technode, China recorded a trade deficit of $233.4 billion for semiconductors in 2020. For crude oil, it was “only” $185.6 billion. Despite the deficit, the People’s Republic recorded a trade surplus of around $590 billion across all commodity groups in 2020, and in 2021 the surplus even climbed to $676 billion. Incidentally, 60 percent of imported semiconductors in 2020 were components for China’s export products such as tablets and other electronic goods.

After Washington placed China’s industry leader, Shenzhen-based SMIC, on its 2020 Entity List, the company struggled to make advanced 7-nanometer chips. “SMIC lacks the machine tools to make them,” researcher Weinstein wrote. US export controls had crippled Huawei’s chip subsidiary HiSilicon. That is part of the reason China plans the domestic production of 70 percent of the chips needed for its tech and auto sector in 2025. But the target is vaguely formulated; and even then, it will still have to source many of the countless preliminary products from abroad.

Despite all the measures to strengthen China’s position as a science and technology hub, the Communist Party is struggling to build domestic supply chains for key raw materials such as semiconductors and gas turbines, Weinstein writes. China will likely remain reliant on foreign equipment well into the 2020s, he adds. Moreover, China’s path to foreign technology leads primarily through US allies such as Australia, Japan, South Korea, and the United Kingdom.

China also has to buy raw materials from geopolitical rivals – such as natural gas for the winter (China.Table reported). Meanwhile, China buys 60 percent of its iron ore from Australia. Beijing’s relations with Canberra are currently at rock bottom. China has been pestering Australia with punitive tariffs or import bans on beef, lobster, barley, and wine, for example, since Canberra called for an independent investigation into the origins of COVID-19. Australia has since joined several security alliances implicitly aimed at China. Recently, it signed a partnership with Japan (China.Table reported).

So far, Beijing has not dared to touch iron ore imports from Down Under. But China is not pleased with its dependence on Australian ore. The People’s Republic is therefore searching for alternatives. In 2020, it found one in the Simandou hill range in the West African country of Guinea. It is said to have the world’s largest deposit of undeveloped high-quality iron ore. In addition to developing the mine, 650 kilometers of railroad and a modern ore port have to be built. In 2020, China secured two of four sections of the planned mine as part of a consortium with French and Singaporean companies.

But Guinea is politically unstable. In September 2021, a military coup overthrew President Alpha Conde. Since then, the coup leader, Colonel Mamady Doumbouya has been in power. Beijing criticized the coup – which is unusual for China. After all, no one knows whether the army will now acknowledge the mining treaty. But China is already dependent on Guinea: The country supplies the Chinese with 55 percent of its bauxite demand for its aluminum industry.

While China’s package delivery services used to pride themselves on constantly surpassing each other in the number of shipped deliveries, a new trend has now emerged: Who is the greenest? Suddenly, packaging sustainability has gained significant importance in the competition between the big players of the People’s Republic.

Cainiao, the logistics division of e-commerce retailer Alibaba, already began setting up large collection stations for cardboard boxes in front of residential buildings several years ago. This allows residents to dispose of the packaging of their deliveries right away so that they can be recycled. Alternatively, they can also take them back to the respective collection station. Cainiao is said to already offer more than 80,000 such collection stations nationwide.

JD.com’s logistics division and household appliance supplier Suning are focusing on “going green” in the production of their packages. Both have launched so-called green packaging programs. Alibaba, meanwhile, has announced the highly ambitious goal of reaching carbon neutrality by 2030. Together with retailers and consumers, the e-commerce giant wants to reduce its CO2 emissions by 1.5 gigatons by 2035. The e-commerce industry is responsible for around 80 percent of deliveries in the People’s Republic.

Due to increasing urbanization and a further growing middle class, the delivery business has grown immensely in recent years. In 2021, delivery services will have delivered a total of 108.5 billion packages. That’s 30 percent more packages than in 2020, despite higher energy prices, the economic impacts of pandemic measures, and recurring lockdowns.

However, the newly gained awareness of logistics companies for greater environmental protection is not as much owed to their guilty consciences about climate change. Rather, it is the result of increasingly stricter regulations from Beijing, which is why companies are now looking to make their supply chains more sustainable. For example, the State Post Bureau, together with the Ministry of Commerce and the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), announced a new law in early January to encourage package delivery services to use even more recycled packaging materials.

On January 6th, the State Post Bureau announced eco-friendly product certification for packaging used by express delivery services to “improve the quality and efficiency of the industry.” Package delivery services are to increasingly use these certified products in the future. The proportion is required to be 90 percent by the end of the year.

In addition, authorities want to standardize the processes of packaging operations and thus reduce the consumption of packaging materials such as corrugated board base paper and adhesive tapes. By the end of the year, the number of recyclable boxes is expected to rise to 10 million, and the number of recycled corrugated cardboard boxes to as much as 700 million.

But it’s not just about cardboard boxes and plastic bags. Bubble wrap, adhesive tapes, and labels are also responsible for generating more than 9 million tons of paper waste and 1.8 tons of plastic waste in China every year. This is shown by data released by the antitrust authority. Experts believe that three-quarters of packaging waste is caused by postal services.

Beijing wants to change all of that this year – and fast. In addition to mandating that the package delivery industry reduce or recycle used materials, the central government announced a two-year pilot program to encourage the use of recycled materials. Effective immediately.

For years, Beijing has been trying to get companies to recycle by issuing regulations and guidelines. So far, however, the reality looks completely different: The proportion of recycled paper has hardly changed for years. In 2020, the recycling rate of paper and cardboard in China reached 46.5 percent. In 2014, it was even higher at over 48 percent.

The fact that hardly anything has been done so far to protect the environment is likely because the logistics industry has barely been able to keep up with deliveries because of the steadily growing consumption. Instead, package delivery services had to deal with staffing and logistics problems, especially as a result of the recurring lockdowns in the country. Environmental and climate protection was a secondary concern.

A survey on behalf of two environmental protection organizations also shows how little companies have addressed recycling to date. The results were staggering: The delivery services JD Logistics and SF Express used sustainable cardboard boxes or packaging for less than 0.5 percent of all orders. And 70 percent of the companies surveyed stated that they had not used any recycling packaging to date.

Recycling in China has so far been mainly a business model for people at the lower end of society. They buy scrap metal, steel, and plastic from small businesses for a handful of yuan, above all paper from consumers. Towards the end of the day, convoys of cargo bikes take the “recyclables” to state recycling plants outside the city, where they are paid a little more than what they had previously paid the paper collectors.

Whether these new regulations will bring change is something Zhou Jiangming doubts. The project manager of Plastic Free China criticizes that the current regulations mainly affect courier companies, creating a regulatory vacuum between e-commerce retailers and delivery companies. “Solving environmental problems through courier packaging is a systematic work,” Zhou told the online magazine Sixth Tone. Focusing only on one player would not achieve results.

In any case, the logistics company Cainiao has already found its very own approach to increasing its recycling rate: For every cardboard box returned, the customer receives an egg in return.

China’s population has once again grown very slowly – by 480,000 to a population of 1.413 billion in 2021. These figures were published by the National Bureau of Statistics of China in Beijing on Monday. Officials are particularly concerned about the birth rate: According to official figures, the number of newborns fell by 11.5 percent to 10.6 million. The birth rate thus slipped to a drastic 7.5 newborns per 1,000 people. It is the lowest figure recorded in the China Statistical Yearbook since 1978 and also the lowest since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949.

The proportion of people of official working age – i.e., between 16 and 59 – also fell in 2021 from 63.3 percent to 62.5 percent of the total population. Ten years ago, it was still around 70 percent. Demographers expect that this proportion could even fall to 50 percent by 2050. At the same time, China is getting older and older: The number of citizens over 60 years grew from 18.7 percent to 18.9 percent of the total population within one year.

For decades, the Communist Party has kept a close eye on the birth rate: The one-child policy, introduced in 1980, was once intended to limit population growth. When the working-age population began to decline earlier than expected, the government began to rethink: In 2015, the one-child policy was abolished; from then on, couples were allowed to have two children. However, this only caused a slight increase in births for a short time, as current figures show. Since May 2021, couples are allowed to have up to three children.

On Monday, the statistics office cited the Covid pandemic to be one of the factors causing the renewed decline in births. Other external factors are also keeping couples from having more children: high housing costs, education and health costs, cramped living conditions, and job discrimination against mothers. Meanwhile, the government is promoting more births with tax benefits (China Table reported).

In light of fewer births, fewer employed, and a growing number of elderly citizens, experts are warning about a “demographic time bomb”. Soon, the People’s Republic might not have enough people to care for the growing number of elderly. rad

Because of rising new Covid infections, the Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (February 4-20) has halted the free sale of tickets. Considering the serious and complicated situation and for the safety of all participants and visitors, it was decided to stop selling tickets, BOCOG said Monday. The available capacity will be used to invite specific groups of viewers instead.

Those selected as spectators are also expected to strictly adhere to COVID-19 regulations before, during, and after each event. This is said to be a prerequisite for the safe and smooth holding of the Games. According to reports, the organizers have already started inviting selected spectators for the opening of the Games through authorities.

Even the athletes are not allowed to move freely and are confined to strictly separated areas instead. It’s a kind of bubble where athletes, volunteers, journalists, and officials will stay – isolated from the rest of the country. They are required to test themselves daily and are not allowed to have any contact with the outside world. This is to prevent the introduction of the Coronavirus.

Foreign spectators are not allowed to attend the Games anyway. This was already decided on in September. At the Summer Games in Tokyo last year, no visitors were allowed at all.

Meanwhile, the number of new Covid infections in China reached its highest level since March 2020 on Monday, with 223 new cases reported nationwide, including 80 in the virus-hit port city of Tianjin and an additional 9 in Guangzhou in southern China. Another 68 cases were reported in the central province of Henan, where partial lockdown measures are in place for several million residents and a massive testing campaign has been underway. The first Omicron case has been registered in Beijing over the weekend (China.Table reported). rad

China’s President Xi Jinping opened the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) online conference “Davos Agenda” on Monday. In his address, Xi called for the stabilization of the global economy and pleaded for greater international cooperation. In times of the Covid pandemic, it would be vital to preventing the global economy from suffering another slump, Xi said.

China will begin the Year of the Tiger in a few days. The tiger symbolizes courage and strength – qualities that the countries of the world should also adopt to overcome the current challenges. Xi also urged the industrialized countries not to spend less money in these times. If they were to slow down or even reverse their monetary policy, this would have negative effects on the global economy and financial stability, Xi warned. Developing countries would have to bear the brunt of such a policy. These countries have already been hit hard by the pandemic, and many have fallen back into poverty and instability.

The World Bank recently warned of a significant slowdown in the global economy. This year, the global economy is expected to grow by 4.1 percent, followed by 3.2 percent in 2023. Poorer countries, in particular, are therefore under pressure.

“Let us join hands with full confidence, and work together for a shared future,” China’s president appealed. The fight against Covid, especially, would be a matter of joining forces to put an end to the pandemic. Xi stressed the importance of vaccines and their fair distribution to close the global vaccination gap. China would continue to actively participate in international cooperation to fight the pandemic.

Other speakers on the program include UN Secretary-General António Guterres and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Germany’s Chancellor Olaf Scholz plans to attend the virtual Davos Dialogue on Wednesday.

The World Economic Forum in Davos, which traditionally takes place in mid-January, had been postponed due to the Covid situation. Instead, the foundation had announced that it would bring leaders together digitally. rad

Peng Jingtang takes up his new post with a pithy promise. As chief of the Hong Kong garrison of the People’s Liberation Army, pledges to “perform defense duties in accordance with the law, resolutely defend national sovereignty, security, and development interests, and firmly safeguard Hong Kong’s long-term prosperity and stability.”

Peng’s words may well be understood as a threat to the remaining pro-democracy forces in the city. Beijing sent a clear signal by appointing the Major General as local PLA commander, who also felt empowered to have a say in the city’s security policy. Under the Basic Law, commonly referred to as Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, Beijing has sovereignty over Hong Kong’s foreign and defense policies. Between the lines, Peng was relatively blunt in stating that the Chinese government is prepared to potentially use the military against the people of Hong Kong in the future.

Last week, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam already assured the local commander-in-chief that her government would work closely with Peng. The chances that Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protest movement will flare up again are slim to none. After all, nearly all of the opposition’s leading figures have been arrested or have fled the country. But Beijing has learned from its own experiences that authoritarian governance works primarily through deterrence. A notorious military leader with experience in the supposed fight against terror is a perfect warning signal.

Because Peng Jingtang commanded the paramilitary People’s Armed Police in Xinjiang before his assignment to Hong Kong. Since 2018, he has also been involved in the arrests of hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs. Around one million people are currently held in internment camps. Beijing defends the existence of the camps by citing, among other things, the threat of terrorism in the region. Several governments, including the US, on the other hand, have classified Beijing’s actions in Xinjiang as genocide.

That Peng’s transfer to Hong Kong is not owed to random chance but was a deliberate move is confirmed by President Xi Jinping’s signature under the appointment of the new chief. Previously, Xinjiang’s security chief had already been transferred (China.Table reported). Wang Junzheng was assigned to Tibet after nearly two years. The security situation there has also been extremely tense for years. grz

Jingwei Jia has left Swiss reinsurer Swiss Re. After 15 years with the company, and most recently six years as CEO of Greater China, Jia left the Zurich-based group at the beginning of January. His interim successor is Jonathan Rake, previously CEO for the Asia Pacific.

Elvis He is the new Head of Technology, Media and Telecom for China at Swiss bank UBS Group AG. He was previously Head of TMT at Hong Kong-based Canon Law Society of America (CLSA), a subsidiary of Shenzhen investment bank CITIC Securities, for four years.

New Chinese tennis hope: 19-year-old Zheng Qinwen celebrated her first victory in a Grand Slam tournament on Monday night. She defeated Belarusian Alyaksandra Sasnovich in three sets at the Australian Open in Melbourne. Reaching the second round earns Zheng prize money of $140,000, well over double what she has earned so far in her career. China’s tennis fans can thus hope for a new star after 35-year-old Peng Shuai had to abruptly end her career a few weeks ago following her allegations of sexual assault against a senior party cadre.