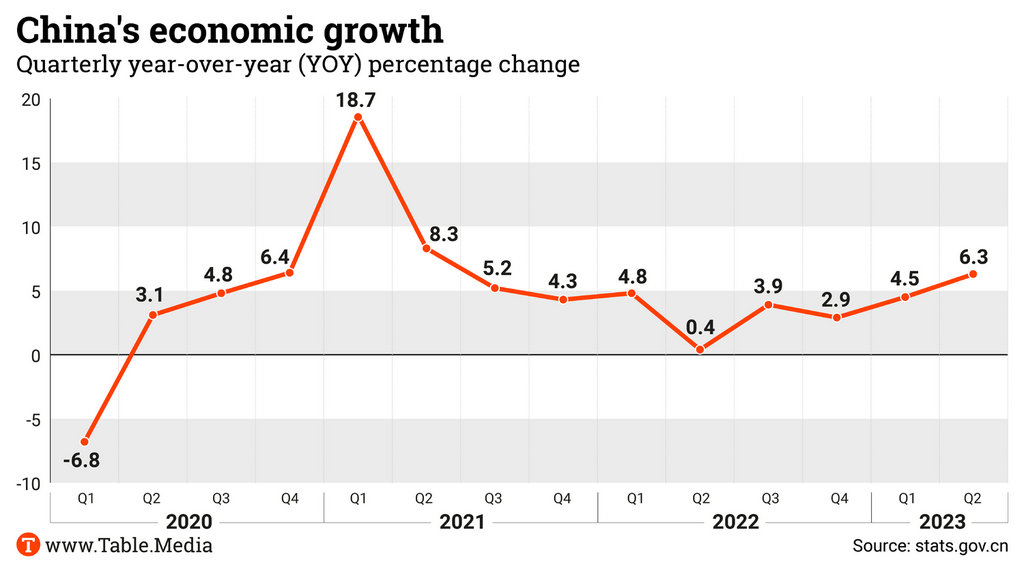

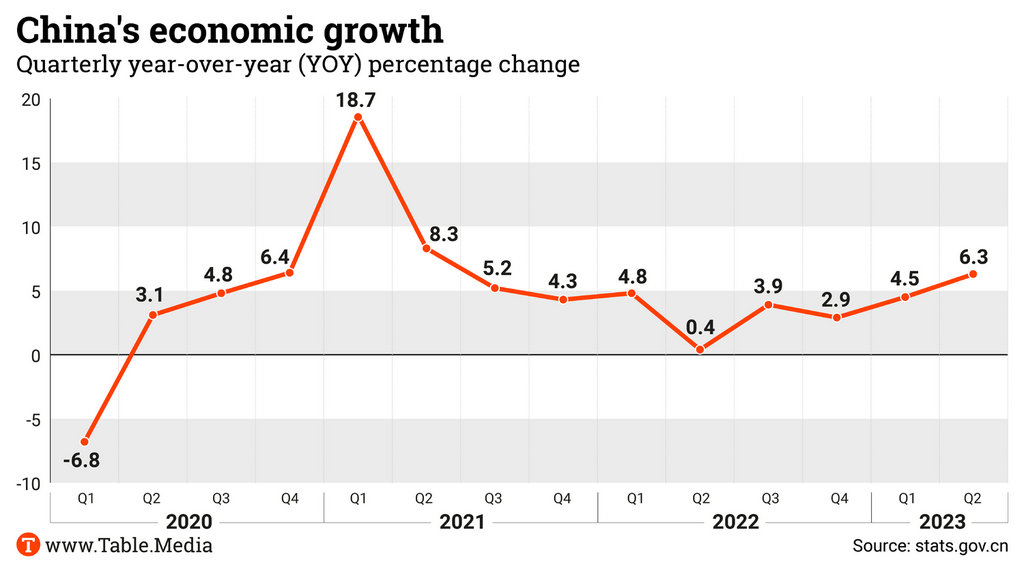

6.3 percent economic growth – that actually sounds pretty decent. And yet analysts are not pleased. After all, the impressive figure is based on a comparison with the second quarter of 2022, when large parts of the country, including the financial metropolis of Shanghai, experienced harsh Covid lockdowns. China’s economy grew by a mere 0.8 percent in the second quarter compared to the first quarter of the year. So economic recovery remains absent in the Far East as well.

The Chinese leadership is not happy about Putin’s war of aggression against Ukraine, either. And yet Beijing continues to back the Russian ruler. If Putin were to be overthrown, either a pro-Western oligarch would come to power. Beijing would then find itself isolated. Or someone of Prigozhin’s caliber would take control in the Kremlin. It is essential for Beijing that Russia does not descend into chaos, analyzes Christiane Kuehl – a country with which China shares a 4300-kilometer border and maintains a strategic partnership. Despite Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Beijing statistics office on Monday reported growth of 6.3 percent for the second quarter and 5.5 percent for the first half of the year. This is a strong plus, which speaks for a stabilization of the situation after the economic reports looked consistently bleak in the past months. Despite weak key data, the government apparently can avoid a plunge. “We don’t think today’s data will push Beijing to step up stimulus measures,” write experts at securities firm Nomura.

Many economists predict a growth rate of around five percent for the year. This is significantly more than is expected for the Eurozone, the USA or Japan. The International Monetary Fund forecasts a level of about one percent. For Germany, stagnation is expected at best.

Economist Ben Shenglin of Zhejiang University expressed confidence at the Table.Live-Briefing that the government will be able to boost both consumption and investment enough to meet its targets without an oversized stimulus package. In fact, government spending is rising strongly. Sooner or later, this should improve the recently negative sentiment.

The willingness to consume is there, he said, but needs to be reactivated. “The importance of consumption as a growth driver is currently increasing rapidly,” Ben said. However, the low national deficit still leaves plenty of room for strong promotion of high-tech industries in particular. That is currently happening, he said. The government in Beijing is supporting weakening domestic demand through public investment and more favorable financing, while the situation in the real estate sector at least appears to be stabilizing, said economist Klaus-Jurgen Gern of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel).

Economists like Gern still consider growth to be shaky. Because the impressive figure of 6.3 percent is the result of a comparison with the second quarter of 2022, when large parts of the country, including the financial metropolis of Shanghai, were under strict Covid lockdowns.

The statistics bureau acknowledged Monday that the recovery of China’s economy after the end of the pandemic had fallen short of expectations. While recovery is evident, the global environment is “complicated,” it said. With that, Beijing appears to blame weak foreign trade, particularly for the slow recovery. But that is only part of the truth.

In fact, Chinese customs data released last week show that foreign demand has collapsed. China’s exports have been declining for months, and in July, they plummeted by as much as 12.4 percent. But imports are also slowing – a clear sign of home-grown problems and reluctant consumption by the Chinese.

The severe weakness of the domestic economy was underlined by a whole series of new data on Monday:

Western experts take a much more pessimistic view of the economic situation than experts in China. “2023 is looking like a year to forget for China,” Harry Murphy Cruise, a Moody’s Analytics economist, wrote Monday in an analysis of the growth figures. Consumers held back on spending and saved money instead. Businesses were hardly investing, while a budding recovery on the real estate market earlier this year had “fizzled out” again, he said. Further government aid for the real estate and construction sectors is expected. But these “won’t be a silver bullet” for the economy.

Economists are also concerned about the price trend in China. Unlike soaring prices in Europe, they are at risk of falling in China, which is also bad news. As the Beijing National Bureau of Statistics of China announced last week, the consumer price index remained unchanged year-on-year in June, having already risen only slightly by 0.2 percent in the previous month. The index thus fell to its lowest level in two years. So there is a threat of deflation if the government does not take countermeasures.

German companies had also expected more from China this year. “Demand from China in the coming months will not provide the lifeline for the German economy that it still did during the global financial crisis,” IfW economist Gern said. “Since opening its zero-covid policy, China has not really picked up momentum,” Volker Treier, Head of Foreign Trade at the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce (DIHK), also said Monday.

According to Karl Haeusgen, President of the German Mechanical Engineering Industry Association (VDMA), the slump is increasingly felt in his sector. “Important customer industries are holding back on investments and local governments lack the financial resources for new large-scale projects,” the VDMA president said during a visit to Beijing last week, according to a statement.

Hopes of a rapid economic recovery had not been fulfilled. According to a survey conducted by the VDMA among its member companies in April, around 40 percent of respondents still expected the business situation to improve in the following six months. “Today we realize that the upswing will still be a while coming,” Haeusgen said. For example, a survey by the German Chamber of Commerce in China also found that more than half of German companies expect business prospects to remain unchanged or even worsen in 2023. Joern Petring/Finn Mayer-Kuckuk/rtr

A few weeks after the Wagner rebellion in Russia, President Vladimir Putin seeks normality. He has already met with the rebellious Wagner boss Yevgeny Prigozhin. Behind the scenes, however, heads are said to be rolling. For instance, General Sergei Surovikin, the deputy commander of the Ukraine war who allegedly sympathizes with Prigozhin, has not been seen since the rebellion; he is supposedly taking a break. One question is particularly important from Beijing’s perspective: Is Russia still stable?

Various circulating reports are likely to cause concern. For example, some voices are already calling for the removal of Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and Chief of General Staff Valery Gerasimov – as Prigozhin had already demanded during his march on Moscow. And in southern Ukraine last week, Russia lost two generals popular with the troops. Oleg Zokov was killed by a Ukrainian missile fired at his headquarters; Ivan Popov was fired after criticizing army leaders. The situation is said to be uneasy among the troops on the ground.

As always, none of these reports can be independently verified. It is unknown just how much China’s President Xi Jinping knows about all of this. But one thing is clear: For him and the Chinese Communist Party, it is important that Russia does not descend into chaos – a country with which China shares a 4300-kilometer border and maintains a strategic partnership, despite Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. The relationship between the two giant empires has never been completely relaxed. And what has now happened there is unimaginable from a Chinese perspective: A private army formed past the state marches toward the capital, seemingly unopposed for hours.

“When 5,000 to 8,000 mercenaries march toward Moscow, and even nearly arrive there, it either means that the state is brittle and unable to act. Or it means that Prigozhin had supporters, which points to a schism among Russian elites,” says Sebastian Hoppe, an Eastern Europe expert at the Script Cluster at Freie Universität Berlin. “Both are harmful to Sino-Russian relations from Beijing’s perspective.” But it is too early to tell if cracks are already forming in the relationship, Hoppe told Table.Media. In any case, a diplomatic meeting between China and Russia on missile defense took place as usual a few days ago.

As usual, no word is leaking out from the party’s top. But some Chinese scholars “point to the increasingly visible weaknesses in Russia’s economy, military and technological advancement,” writes Thomas des Garets Geddes, who regularly evaluates papers by Chinese scholars for his newsletter Sinification – including shortly after the uprising. “With this Wagner mutiny, political tensions within Russia will be further exacerbated,” writes Feng Yujun, Director of the Center for Russian and Central Asian Studies at Shanghai’s Fudan University and one of the few Chinese critics of Moscow since the war began. The incident will have “far-reaching repercussions on Russia’s future. This deserves our utmost attention.” The volatility of Russian politics will remain, he said.

Wang Siyu of the Shanghai Academy of Global Governance and Area Studies writes, “This mutiny and the fact that it has gone unpunished has now set a precedent. Will others in Russia decide to express their dissatisfaction in a similar way?”

An interesting side note is that China likes to use the services of Wagner mercenaries in Africa. In early July, their mercenaries rescued a group of Chinese miners from a Chinese-operated mine near Bambari in the Central African Republic from an attack by local militants, Wagner posted on Telegram. The Chinese embassy had directly asked Wagner for help. Such cooperation between Beijing and private security forces is “very common,” the South China Morning Post reported, citing military sources. Wagner announced the latest operation to show Putin that they wanted to help Russia strengthen ties with China, the newspaper quoted an unnamed Chinese military veteran as saying.

Since the start of the war, China’s desire for stability in Russia has repeatedly raised the question of whether it would not supply Putin with weapons to prevent a crushing defeat in Ukraine and, thus, a potential system collapse. Hoppe does not believe so. In any event, he said, Beijing’s military is currently under heavy Western scrutiny, which it knows. Wagner is considered to be another obstacle. If China “ever considered supplying Russia with weapons, the new situation should now be factored into the calculation. Because it may not be possible to guarantee into whose hands such weapons will end up. That’s a huge factor of uncertainty.”

This uncertainty also affects the espionage aspect. The intelligence services of the People’s Republic of China “struggle to understand the country’s politics,” writes US expert Joe Webster on his blog China Russia Report. Now, he says, Russian contacts who had knowledge of or even sympathized with the mutiny may also be exposed. “Beijing will increasingly focus intelligence resources, especially signals intelligence (SIGINT), on Russia,” Webster expects.

Whether this will allow China to predict an overthrow is uncertain. “In the end, Chinese politicians know just as little as we do about what state the Russian state is really in,” Hoppe says. “After all, it’s possible that things will continue as they are now for several more years there, because Putin’s networks inside the Russian state are holding the whole thing together to a sufficient degree.” Hoppe believes Beijing accepts the situation for now – but eyes it with caution. Joe Webster is not certain: “Owing to Beijing’s interests in maintaining a pro-PRC regime in Moscow, Chinese security services will also be tempted to intervene in Russian domestic politics. It’s possible they are doing so already.”

Because Putin’s fall would be a bad scenario for China. Hoppe believes it is difficult, given the personnel available, for Beijing to execute its plans for building a threatening bloc against the United States, even with successors. “China prefers Putin in any case rather than deal with the uncertain other plausible candidates to power. Many of these politicians are fundamentally suspicious of foreign countries, including China – or they are extremely national-chauvinistic,” he says. “At the other end of the spectrum would be Western-oriented politicians like Alexei Navalny. They, too, are difficult from China’s point of view. Technocrats close to Putin with whom China would get along well – such as the head of state oil company Rosneft Igor Sechin – have no political profile.”

A planned US visit by a top Taiwanese politician is causing new tensions with China. Taiwan announced Monday that Vice President William Lai will visit the United States next month. The visit is officially a stopover on the flight to and from Paraguay, but it will give Lai the opportunity to meet with US officials.

The reaction of the communist leadership in Beijing followed quickly: It dispatched a total of 16 warships around the island of Taiwan – more than ever before, reports the Taiwanese Ministry of Defense.

The regular stopovers in the US used by Taiwanese state representatives on foreign trips have repeatedly been sharply criticized by China. This time, too, the leadership in Beijing immediately protested. “China is firmly opposed to any form of official exchanges between the United States and Taiwan,” a Foreign Ministry spokesman said. “We firmly reject Taiwan independence separatists visiting the US under any name and for any reason, as well as any form of the US connivance and support of the Taiwan independence separatists and their separatist activities.”

As recently as April, a US visit by Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen caused tensions. China responded at the time with military drills around Taiwan. Lai’s trip becomes particularly sensitive because he intends to succeed Tsai in the January elections, and Taiwanese presidential candidates usually visit the United States before an election to discuss their candidacy with representatives. Lai is currently leading in most polls. rtr

China recorded a new temperature record. In the municipality of Sanbao in the northwest of the country, temperatures climbed to 52.2 degrees Celsius on Sunday, according to state media. The previous record was set in 2015 at 50.3 degrees. The development is fueling concerns that last year’s drought could be repeated. China experienced its worst drought in 60 years in 2022.

Despite serious political differences, China and the United States plan to cooperate in the fight against global warming. US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry will hold talks with his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua on Monday. Before the start of the negotiations, Kerry said it was imperative to make progress in the four months before the next global climate summit in Dubai. He called on China to cut methane emissions and reduce the climate impact of coal-fired power generation. rtr

The return of Chinese customers after the end of the Covid pandemic is boosting business at Swiss luxury goods manufacturer Richemont. In the past quarter, the first in the 2023/24 fiscal year, sales climbed 19 percent to 5.32 billion euros after adjusting for currency effects, according to the Geneva-based group.

In Asia, the group’s biggest sales region, jewelry, expensive watches and luxury fashion sales soared 40 percent. In Europe, quarterly sales increased by eleven percent, while in the Americas they declined by two percent.

The company is thus following the trend: The lifting of the Covid measures in China has boosted demand for luxury goods and helped global watch market leader Swatch and British luxury fashion manufacturer Burberry achieve strong sales growth. However, investors had expected even more from Richemont. With a price slump of eight percent, the title slid to the bottom of the Swiss Bluechips. rtr

Richard von Schirach, author and doctor of sinology, died in Germany at the age of 81. Von Schirach, who held a Ph.D. in Chinese studies, lived as a book printer in Taiwan and translated the autobiography “Pu Yi – I was Emperor of China” in 1973. The book was the basis for the 1987 film adaptation “The Last Emperor” screenplay by Italian star director Bernardo Bertolucci. The film won nine Oscars. In 1978, von Schirach founded a consulting and service company for the People’s Republic of China.

Von Schirach was born in Munich in 1942, the son of Nazi Reich Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach. His maternal grandfather was Heinrich Hoffmann, a Nazi photographer made famous by the photographs of Adolf Hitler. In 2005, the author recorded his childhood memories in the autobiographical book “The Shadow of My Father.” In 2012, he published the non-fiction book “The Night of the Physicists,” in which he traces the careers of Werner Heisenberg, Otto Hahn and Carl Friedrich von Weizsacker up to the dropping of the Hiroshima bomb.

His daughter, philosopher Ariadne von Schirach, his son Benedict Wells, and his nephew, lawyer Ferdinand von Schirach, are also active as writers. cyb

Yan Mingfu (1931-2023) died in Beijing on July 3 at the age of 91. He grew up, baptized in a Christian family, in southwest China’s Chongqing. At 18, Yan joined the Communist Party, studied Russian and became Mao Zedong’s chief interpreter. He accompanied the chairman at his meetings with Soviet leaders, translated Beijing’s bitter dispute with Moscow over ideological supremacy during the “Great Polemics China versus Soviet Union.” Yan told me, “I was at the table when the honeymoon turned into cold war.”

This is just his side in the life and suffering of the two Yan. Son Yan Mingfu 阎明复 and his father Yan Baohang 阎宝航 (1895 -1968) are the protagonists of a bizarre Chinese family saga. When the party accepted Yan Junior in 1949, he was unaware that his father and Christian educator had already been a member of the CP since 1937. But secretly, so no one would know, he was one of Mao’s top agents. The latter’s henchman Zhou Enlai had recruited him conspiratorially.

In his recently published book “Warlords” (Elfenbeinverlag, Berlin 2023), historian and sinologist Rainer Kloubert even calls Yan Baohang a “century spy.” Next to Richard Sorge – or even more than him – Yan became one of the most successful, but also most unknown agents of the 20th century.

Yan found his informants in Chongqing after the ruling Kuomintang party under Chiang Kai-shek made the Yangtze River city its temporary replacement capital after the Japanese invasion of China. As a staff aide to the legendary “young marshal” and warlord Zhang Xueliang, Yan also became acquainted with the Kuomintang elite, Chiang Kai-shek and his wife Soong Meiling. Soon after, he became general secretary for Chiang’s Christian-influenced “New Life” movement.

Yan was able to provide Mao with a steady stream of secrets from within the national government, including real scoops. For example, he obtained the date of Hitler’s plan to invade the Soviet Union in advance. In the week after June 20, 1941, he passed this information on to Mao, who dispatched it to Stalin on June 16. Stalin, as with Sorge, refused to acknowledge it, but thanked Mao in a secret telegram on June 30: “Thanks to your correct information, we were able to declare a state of alert for the Soviet Army before the German attack.”

Yan also informed Mao of Japan’s impending attack on Pearl Harbor in November 1941. The news was passed on to the USA via Stalin. The Kuomintang also informed the United States, but their reaction was also one of suspicion.

In his “Pictorial Arc of the Chinese Civil War,” which he devoted to the fascinating life story of warlord Zhang Xueliang, Kloubert traced the source of Yan’s predictions. Yan was friends with a “brilliant” Chinese mathematician named Chi Buzhou (池步洲). The latter was able to decipher Japan’s secret code in a cryptographic department set up by KMT intelligence chief Dai Li (戴笠) in Chongqing.

Even more important in late 1944 was Yan’s dispatch of exactly where and in what strength Japan’s Kwantung Army was positioned in northeast China. This helped Stalin’s Red Army to quickly defeat Japan’s forces. In 1995, Moscow posthumously awarded Yan Baohang a medal for this.

It was only after 1962 that Yan Baohang let his son in on his glorious double role. But then Mao’s revolution also ate its children; both Junior and Senior Yan fell victim to the chaos of the Cultural Revolution in 1967.

In 1967, the father was taken away first. Denounced as a Kuomintang reactionary, he was imprisoned in Beijing’s new Qincheng political prison, built with Soviet help. Ten days later, his son followed, accused of being a Soviet spy.

The son was imprisoned for seven and a half years, from 1967 to 1975. Only after his release was he told that his father had died in May 1968 – in Qincheng Prison, just a few meters away from him.

We – Ansa correspondent Barbara Alighiero and I – first learned this directly from Yan when we interviewed him in Beijing in September 1999. At the time, he wanted to remind us above all of his father’s achievements.

When I went to see Yan a second time with my wife Zhao Yuanhong in October 2002, we asked him to tell us the grotesque story in more detail. Yan began to tell it, but suddenly lost his composure and cried for minutes.

He was first interrogated by CC special investigators in November 1967, while he was head of the Russian interpreting department for Mao. Without any reason, they accused him of being a Soviet spy. On November 17, two soldiers dragged him before a gathering of 500 Red Guards, who shouted him down. A warrant was read to him and he was handcuffed. During the night, the henchmen took him to Qincheng. Yan was given the number 67124 as his new name. 67 stood for the year, 124 for the number of new prisoners brought in since the beginning of the year.

Ten days earlier, on November 7, his father had been abducted from his home. Again, no one knew where he was taken. Father Yan was also given a number: 67100. “We sat in solitary cells, not knowing about each other.” One day, someone had coughed in the outside corridor, just as his father did. “That’s impossible,” he thought at the time.

When Yan Mingfu was released in 1975, he was told that his father had served time near him and died on May 22, 1968. He later learned that Mao’s wife Jiang Qing, who controlled the detention lists, had ordered that the death of this “counterrevolutionary” not be reported nor his ashes kept. Yan’s Baohang’s wife knew neither where her husband nor her son was and died soon.

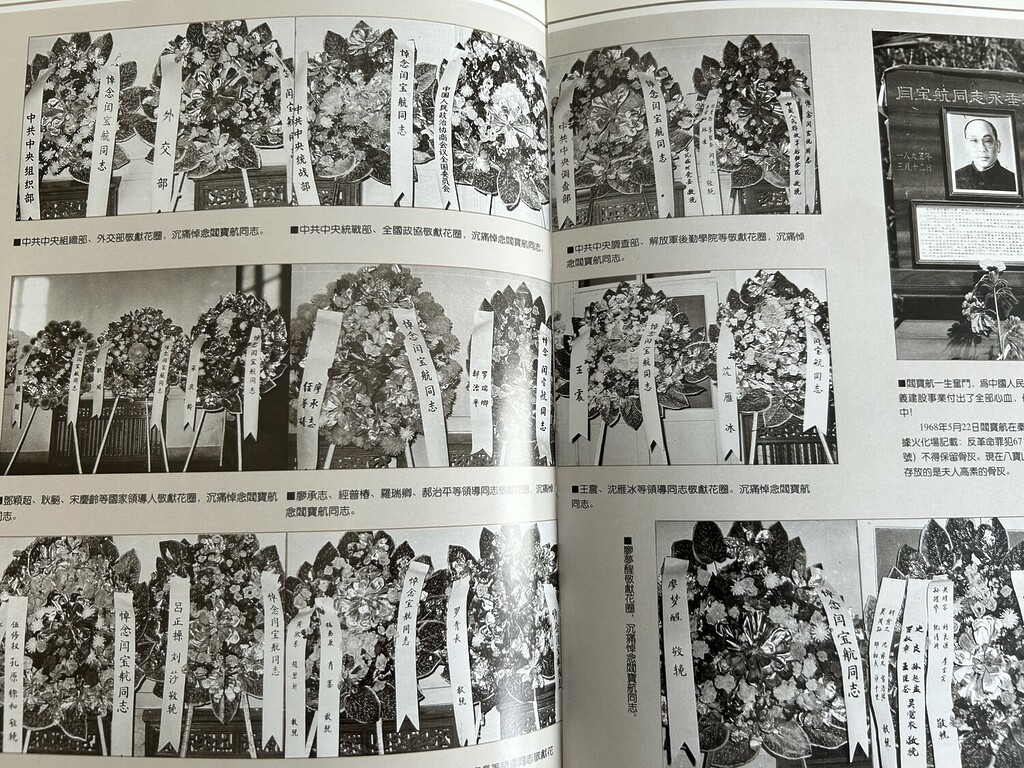

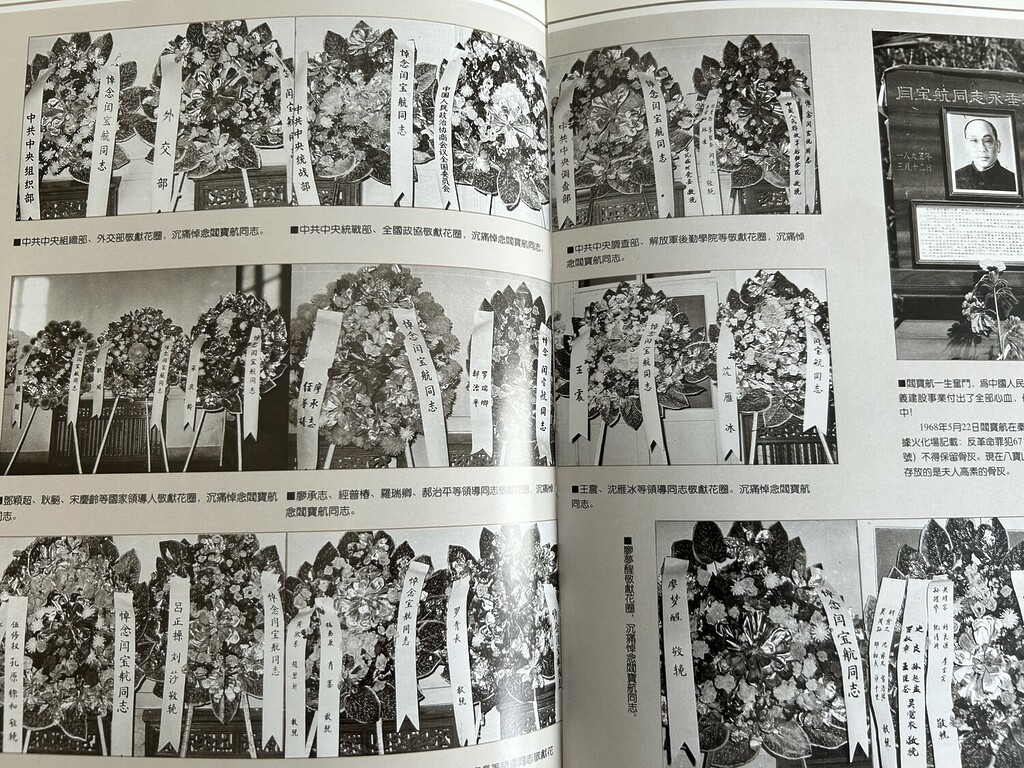

Free once again, Yan Mingfu made every effort to arrange a funeral for his father in Beijing’s Revolutionary Cemetery, partly as a sign of his public rehabilitation. It was held on January 5, 1978, ten years after he had passed away. Beijing limited the number of participants to 100 high-ranking mourners. “But more than 1,000 came,” he recalled.

In the hopeful reform era that followed, Yan climbed the party ladder and was allowed to edit a new “Great Encyclopedia” for China after Mao’s cultural cleansing, on which dozens of once-persecuted scholars collaborated.

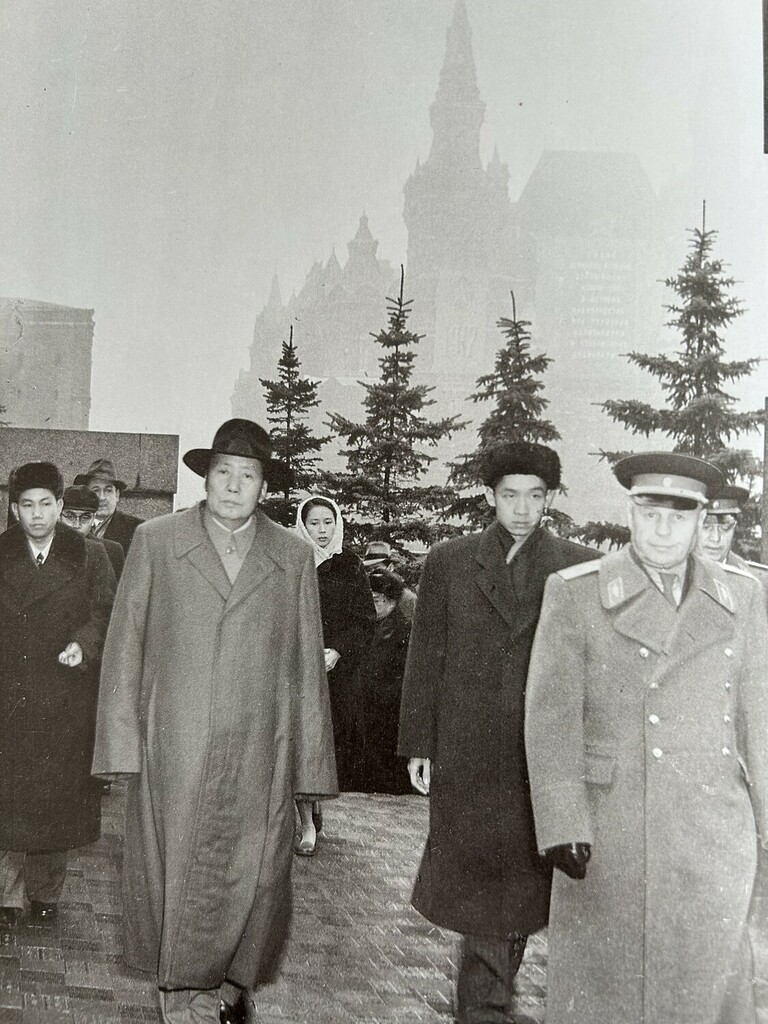

In 1986, Yan was promoted to CC secretary and head of the Communist United Front. In May 1989, Deng Xiaoping brought him to Beijing for the historic reconciliation meeting with Soviet party leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Outside, tens of thousands of students demonstrated for greater freedom. At the request of Zhao Ziyang, the liberal party leader who was later overthrown, Yan attempted to mediate between the hunger strikers on Tiananmen Square and the hardliners in the Beijing leadership. He offered to join the students as a “hostage” to ensure that the party leadership met their demands.

Yan got caught between the fronts, failed to stop the massacre on June 4, 1989, and was stripped of all party posts a month later. But Deng did not abandon him completely. He allowed Yan to lead the Civil Affairs Ministry as vice chief after 1991 and found China’s Welfare Association (中华慈善总会). Online obituaries today call Yan the “father of China’s modern philanthropy” 中国现代慈善.

The bizarre saga of the two Yan does not find a happy ending in Xi Jinping’s China. Yan’s recent death was ignored by party officials. The news spread only on the Internet. The semi-official financial magazine Caixin was the only one allowed to publish a memorial essay by Deng Rong, Deng Xiaoping’s daughter.

Ten days after Yan’s death, the authorities finally allowed a funeral service to be held last Thursday. The party had previously settled on the lowest form of recognition of his merits in CP jargon. Yan had been an “outstanding party member and loyal communist fighter.”

Critical voices were excluded. The grand dame of Beijing’s dissidents, Gao Yu, tweeted that police officers lined up outside her apartment at six in the morning to prevent her from attending the funeral. She wrote: “We mourn him because during June 4, 1989, he wanted to solve the issue of the student movement under Zhao Ziyang’s ‘Way of Democracy and Law’.” 我們悼念他因為8964期間他執行趙紫陽的 “在民主與法制的道路上解決學運” Bloggers tried to bypass censorship for their online protests. Instead of forbidden words like “Yan and Tiananmen,” they wrote “person for dialogue on the square” 广场对话的人.

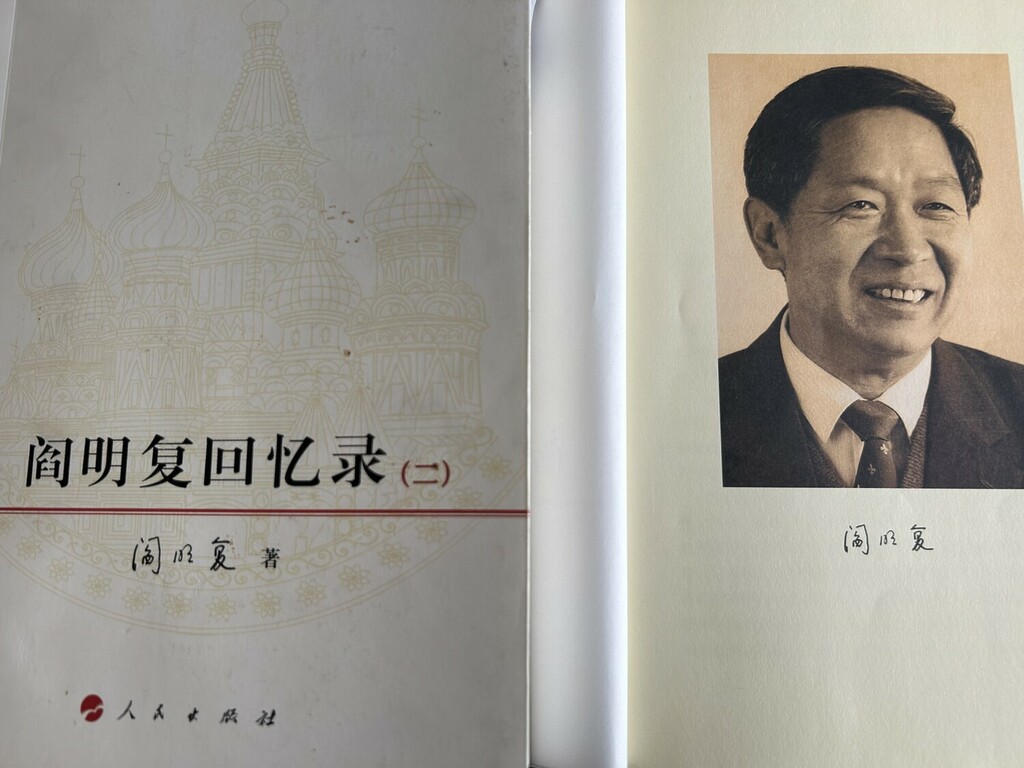

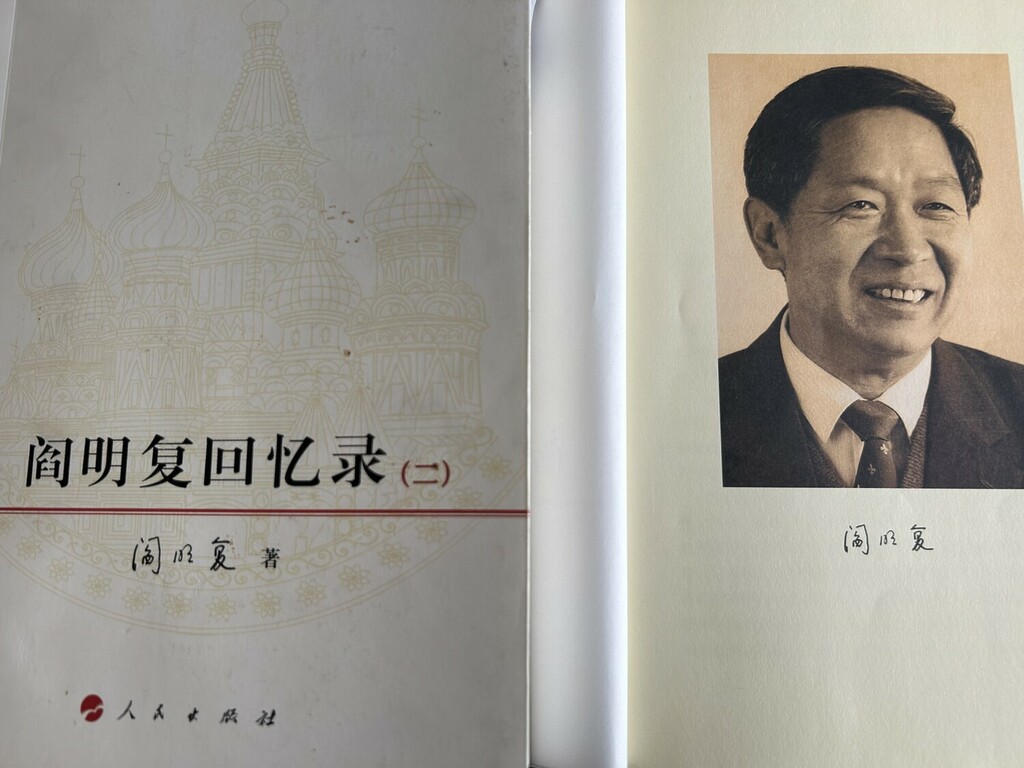

The saga of the two Yans does not fit in with today’s re-ideologized image of China, since the socialist history of the People’s Republic has been rewritten and glossed over and Mao’s crimes and the horrors of the Cultural Revolution relativized under Xi Jinping since 2017. That is Beijing’s problem with loyalist Yan Mingfu, especially after he published his two-volume memoirs in 2015. Nowadays, he would hardly get them past the censors. In 2015, renowned Chinese historians like Shen Zhihua or essayists like Ding Dong called the 1116 pages a treasure trove “of historical truth” and unadulterated history of the People’s Republic about the first 20 years of Sino-Soviet relations and the “Great Polemic” that almost resulted in war.

Yan writes, “It was a historical tragedy.” Mao had used it “as a prelude to his Cultural Revolution.” Yan describes Mao’s megalomania in his fight against Khrushchev with the words, “Who shall lead the socialist camp ideologically and that the east wind will defeat the west wind.” Reading between Yan’s lines today, one can’t help but think of Xi Jinping’s power fantasies.

Yan’s memoir tells many anecdotes, some with sarcastic punchlines. When Khrushchev announced in Beijing that he would increase the Soviet development aid projects for China that had been agreed upon for the first five-year plan (1953 to 1957), Yan wrote: “A special project then came along. Moscow wanted to help us build Qincheng Prison. Then during the Cultural Revolution, my father and I would end up there.”

Xiao Guo-Deters joined Cosco Shipping Europe this month as Manager of Strategy Development. Previously, she was Head of Marketing DACH Region for the Chinese private equity firm CS Capital, also in Hamburg.

Xindao Mao has moved to the post of Manager of Chromatography China at Sartorius Stedim Biotech in Shanghai. Previously, he worked for the same company, where he has been employed for almost four years, as Strategic Marketing Manager in Goettingen.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

The city of Shijiazhuang in the east of the country is not experiencing extreme temperatures like those in northwest China (see News). But with temperatures of 36 degrees, a little refreshment can’t hurt. These two at least seem to have no problem going home with soaking-wet clothes. But given the heat, they’ll probably be dry again by then anyway.

6.3 percent economic growth – that actually sounds pretty decent. And yet analysts are not pleased. After all, the impressive figure is based on a comparison with the second quarter of 2022, when large parts of the country, including the financial metropolis of Shanghai, experienced harsh Covid lockdowns. China’s economy grew by a mere 0.8 percent in the second quarter compared to the first quarter of the year. So economic recovery remains absent in the Far East as well.

The Chinese leadership is not happy about Putin’s war of aggression against Ukraine, either. And yet Beijing continues to back the Russian ruler. If Putin were to be overthrown, either a pro-Western oligarch would come to power. Beijing would then find itself isolated. Or someone of Prigozhin’s caliber would take control in the Kremlin. It is essential for Beijing that Russia does not descend into chaos, analyzes Christiane Kuehl – a country with which China shares a 4300-kilometer border and maintains a strategic partnership. Despite Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Beijing statistics office on Monday reported growth of 6.3 percent for the second quarter and 5.5 percent for the first half of the year. This is a strong plus, which speaks for a stabilization of the situation after the economic reports looked consistently bleak in the past months. Despite weak key data, the government apparently can avoid a plunge. “We don’t think today’s data will push Beijing to step up stimulus measures,” write experts at securities firm Nomura.

Many economists predict a growth rate of around five percent for the year. This is significantly more than is expected for the Eurozone, the USA or Japan. The International Monetary Fund forecasts a level of about one percent. For Germany, stagnation is expected at best.

Economist Ben Shenglin of Zhejiang University expressed confidence at the Table.Live-Briefing that the government will be able to boost both consumption and investment enough to meet its targets without an oversized stimulus package. In fact, government spending is rising strongly. Sooner or later, this should improve the recently negative sentiment.

The willingness to consume is there, he said, but needs to be reactivated. “The importance of consumption as a growth driver is currently increasing rapidly,” Ben said. However, the low national deficit still leaves plenty of room for strong promotion of high-tech industries in particular. That is currently happening, he said. The government in Beijing is supporting weakening domestic demand through public investment and more favorable financing, while the situation in the real estate sector at least appears to be stabilizing, said economist Klaus-Jurgen Gern of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel).

Economists like Gern still consider growth to be shaky. Because the impressive figure of 6.3 percent is the result of a comparison with the second quarter of 2022, when large parts of the country, including the financial metropolis of Shanghai, were under strict Covid lockdowns.

The statistics bureau acknowledged Monday that the recovery of China’s economy after the end of the pandemic had fallen short of expectations. While recovery is evident, the global environment is “complicated,” it said. With that, Beijing appears to blame weak foreign trade, particularly for the slow recovery. But that is only part of the truth.

In fact, Chinese customs data released last week show that foreign demand has collapsed. China’s exports have been declining for months, and in July, they plummeted by as much as 12.4 percent. But imports are also slowing – a clear sign of home-grown problems and reluctant consumption by the Chinese.

The severe weakness of the domestic economy was underlined by a whole series of new data on Monday:

Western experts take a much more pessimistic view of the economic situation than experts in China. “2023 is looking like a year to forget for China,” Harry Murphy Cruise, a Moody’s Analytics economist, wrote Monday in an analysis of the growth figures. Consumers held back on spending and saved money instead. Businesses were hardly investing, while a budding recovery on the real estate market earlier this year had “fizzled out” again, he said. Further government aid for the real estate and construction sectors is expected. But these “won’t be a silver bullet” for the economy.

Economists are also concerned about the price trend in China. Unlike soaring prices in Europe, they are at risk of falling in China, which is also bad news. As the Beijing National Bureau of Statistics of China announced last week, the consumer price index remained unchanged year-on-year in June, having already risen only slightly by 0.2 percent in the previous month. The index thus fell to its lowest level in two years. So there is a threat of deflation if the government does not take countermeasures.

German companies had also expected more from China this year. “Demand from China in the coming months will not provide the lifeline for the German economy that it still did during the global financial crisis,” IfW economist Gern said. “Since opening its zero-covid policy, China has not really picked up momentum,” Volker Treier, Head of Foreign Trade at the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce (DIHK), also said Monday.

According to Karl Haeusgen, President of the German Mechanical Engineering Industry Association (VDMA), the slump is increasingly felt in his sector. “Important customer industries are holding back on investments and local governments lack the financial resources for new large-scale projects,” the VDMA president said during a visit to Beijing last week, according to a statement.

Hopes of a rapid economic recovery had not been fulfilled. According to a survey conducted by the VDMA among its member companies in April, around 40 percent of respondents still expected the business situation to improve in the following six months. “Today we realize that the upswing will still be a while coming,” Haeusgen said. For example, a survey by the German Chamber of Commerce in China also found that more than half of German companies expect business prospects to remain unchanged or even worsen in 2023. Joern Petring/Finn Mayer-Kuckuk/rtr

A few weeks after the Wagner rebellion in Russia, President Vladimir Putin seeks normality. He has already met with the rebellious Wagner boss Yevgeny Prigozhin. Behind the scenes, however, heads are said to be rolling. For instance, General Sergei Surovikin, the deputy commander of the Ukraine war who allegedly sympathizes with Prigozhin, has not been seen since the rebellion; he is supposedly taking a break. One question is particularly important from Beijing’s perspective: Is Russia still stable?

Various circulating reports are likely to cause concern. For example, some voices are already calling for the removal of Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and Chief of General Staff Valery Gerasimov – as Prigozhin had already demanded during his march on Moscow. And in southern Ukraine last week, Russia lost two generals popular with the troops. Oleg Zokov was killed by a Ukrainian missile fired at his headquarters; Ivan Popov was fired after criticizing army leaders. The situation is said to be uneasy among the troops on the ground.

As always, none of these reports can be independently verified. It is unknown just how much China’s President Xi Jinping knows about all of this. But one thing is clear: For him and the Chinese Communist Party, it is important that Russia does not descend into chaos – a country with which China shares a 4300-kilometer border and maintains a strategic partnership, despite Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. The relationship between the two giant empires has never been completely relaxed. And what has now happened there is unimaginable from a Chinese perspective: A private army formed past the state marches toward the capital, seemingly unopposed for hours.

“When 5,000 to 8,000 mercenaries march toward Moscow, and even nearly arrive there, it either means that the state is brittle and unable to act. Or it means that Prigozhin had supporters, which points to a schism among Russian elites,” says Sebastian Hoppe, an Eastern Europe expert at the Script Cluster at Freie Universität Berlin. “Both are harmful to Sino-Russian relations from Beijing’s perspective.” But it is too early to tell if cracks are already forming in the relationship, Hoppe told Table.Media. In any case, a diplomatic meeting between China and Russia on missile defense took place as usual a few days ago.

As usual, no word is leaking out from the party’s top. But some Chinese scholars “point to the increasingly visible weaknesses in Russia’s economy, military and technological advancement,” writes Thomas des Garets Geddes, who regularly evaluates papers by Chinese scholars for his newsletter Sinification – including shortly after the uprising. “With this Wagner mutiny, political tensions within Russia will be further exacerbated,” writes Feng Yujun, Director of the Center for Russian and Central Asian Studies at Shanghai’s Fudan University and one of the few Chinese critics of Moscow since the war began. The incident will have “far-reaching repercussions on Russia’s future. This deserves our utmost attention.” The volatility of Russian politics will remain, he said.

Wang Siyu of the Shanghai Academy of Global Governance and Area Studies writes, “This mutiny and the fact that it has gone unpunished has now set a precedent. Will others in Russia decide to express their dissatisfaction in a similar way?”

An interesting side note is that China likes to use the services of Wagner mercenaries in Africa. In early July, their mercenaries rescued a group of Chinese miners from a Chinese-operated mine near Bambari in the Central African Republic from an attack by local militants, Wagner posted on Telegram. The Chinese embassy had directly asked Wagner for help. Such cooperation between Beijing and private security forces is “very common,” the South China Morning Post reported, citing military sources. Wagner announced the latest operation to show Putin that they wanted to help Russia strengthen ties with China, the newspaper quoted an unnamed Chinese military veteran as saying.

Since the start of the war, China’s desire for stability in Russia has repeatedly raised the question of whether it would not supply Putin with weapons to prevent a crushing defeat in Ukraine and, thus, a potential system collapse. Hoppe does not believe so. In any event, he said, Beijing’s military is currently under heavy Western scrutiny, which it knows. Wagner is considered to be another obstacle. If China “ever considered supplying Russia with weapons, the new situation should now be factored into the calculation. Because it may not be possible to guarantee into whose hands such weapons will end up. That’s a huge factor of uncertainty.”

This uncertainty also affects the espionage aspect. The intelligence services of the People’s Republic of China “struggle to understand the country’s politics,” writes US expert Joe Webster on his blog China Russia Report. Now, he says, Russian contacts who had knowledge of or even sympathized with the mutiny may also be exposed. “Beijing will increasingly focus intelligence resources, especially signals intelligence (SIGINT), on Russia,” Webster expects.

Whether this will allow China to predict an overthrow is uncertain. “In the end, Chinese politicians know just as little as we do about what state the Russian state is really in,” Hoppe says. “After all, it’s possible that things will continue as they are now for several more years there, because Putin’s networks inside the Russian state are holding the whole thing together to a sufficient degree.” Hoppe believes Beijing accepts the situation for now – but eyes it with caution. Joe Webster is not certain: “Owing to Beijing’s interests in maintaining a pro-PRC regime in Moscow, Chinese security services will also be tempted to intervene in Russian domestic politics. It’s possible they are doing so already.”

Because Putin’s fall would be a bad scenario for China. Hoppe believes it is difficult, given the personnel available, for Beijing to execute its plans for building a threatening bloc against the United States, even with successors. “China prefers Putin in any case rather than deal with the uncertain other plausible candidates to power. Many of these politicians are fundamentally suspicious of foreign countries, including China – or they are extremely national-chauvinistic,” he says. “At the other end of the spectrum would be Western-oriented politicians like Alexei Navalny. They, too, are difficult from China’s point of view. Technocrats close to Putin with whom China would get along well – such as the head of state oil company Rosneft Igor Sechin – have no political profile.”

A planned US visit by a top Taiwanese politician is causing new tensions with China. Taiwan announced Monday that Vice President William Lai will visit the United States next month. The visit is officially a stopover on the flight to and from Paraguay, but it will give Lai the opportunity to meet with US officials.

The reaction of the communist leadership in Beijing followed quickly: It dispatched a total of 16 warships around the island of Taiwan – more than ever before, reports the Taiwanese Ministry of Defense.

The regular stopovers in the US used by Taiwanese state representatives on foreign trips have repeatedly been sharply criticized by China. This time, too, the leadership in Beijing immediately protested. “China is firmly opposed to any form of official exchanges between the United States and Taiwan,” a Foreign Ministry spokesman said. “We firmly reject Taiwan independence separatists visiting the US under any name and for any reason, as well as any form of the US connivance and support of the Taiwan independence separatists and their separatist activities.”

As recently as April, a US visit by Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen caused tensions. China responded at the time with military drills around Taiwan. Lai’s trip becomes particularly sensitive because he intends to succeed Tsai in the January elections, and Taiwanese presidential candidates usually visit the United States before an election to discuss their candidacy with representatives. Lai is currently leading in most polls. rtr

China recorded a new temperature record. In the municipality of Sanbao in the northwest of the country, temperatures climbed to 52.2 degrees Celsius on Sunday, according to state media. The previous record was set in 2015 at 50.3 degrees. The development is fueling concerns that last year’s drought could be repeated. China experienced its worst drought in 60 years in 2022.

Despite serious political differences, China and the United States plan to cooperate in the fight against global warming. US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry will hold talks with his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua on Monday. Before the start of the negotiations, Kerry said it was imperative to make progress in the four months before the next global climate summit in Dubai. He called on China to cut methane emissions and reduce the climate impact of coal-fired power generation. rtr

The return of Chinese customers after the end of the Covid pandemic is boosting business at Swiss luxury goods manufacturer Richemont. In the past quarter, the first in the 2023/24 fiscal year, sales climbed 19 percent to 5.32 billion euros after adjusting for currency effects, according to the Geneva-based group.

In Asia, the group’s biggest sales region, jewelry, expensive watches and luxury fashion sales soared 40 percent. In Europe, quarterly sales increased by eleven percent, while in the Americas they declined by two percent.

The company is thus following the trend: The lifting of the Covid measures in China has boosted demand for luxury goods and helped global watch market leader Swatch and British luxury fashion manufacturer Burberry achieve strong sales growth. However, investors had expected even more from Richemont. With a price slump of eight percent, the title slid to the bottom of the Swiss Bluechips. rtr

Richard von Schirach, author and doctor of sinology, died in Germany at the age of 81. Von Schirach, who held a Ph.D. in Chinese studies, lived as a book printer in Taiwan and translated the autobiography “Pu Yi – I was Emperor of China” in 1973. The book was the basis for the 1987 film adaptation “The Last Emperor” screenplay by Italian star director Bernardo Bertolucci. The film won nine Oscars. In 1978, von Schirach founded a consulting and service company for the People’s Republic of China.

Von Schirach was born in Munich in 1942, the son of Nazi Reich Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach. His maternal grandfather was Heinrich Hoffmann, a Nazi photographer made famous by the photographs of Adolf Hitler. In 2005, the author recorded his childhood memories in the autobiographical book “The Shadow of My Father.” In 2012, he published the non-fiction book “The Night of the Physicists,” in which he traces the careers of Werner Heisenberg, Otto Hahn and Carl Friedrich von Weizsacker up to the dropping of the Hiroshima bomb.

His daughter, philosopher Ariadne von Schirach, his son Benedict Wells, and his nephew, lawyer Ferdinand von Schirach, are also active as writers. cyb

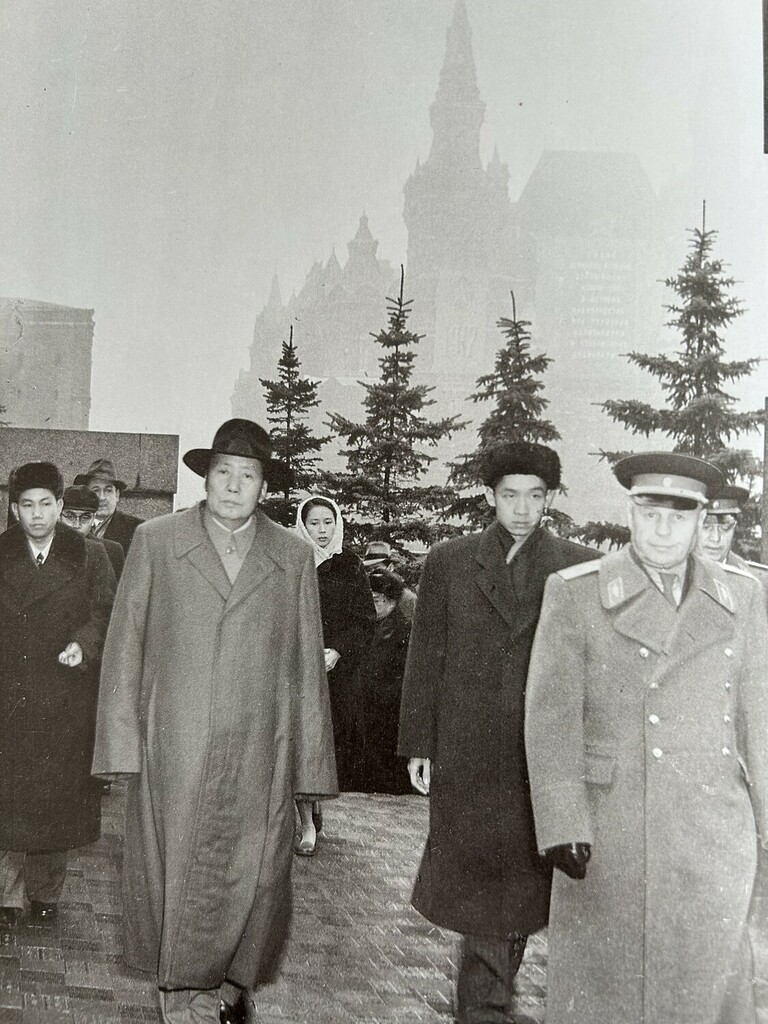

Yan Mingfu (1931-2023) died in Beijing on July 3 at the age of 91. He grew up, baptized in a Christian family, in southwest China’s Chongqing. At 18, Yan joined the Communist Party, studied Russian and became Mao Zedong’s chief interpreter. He accompanied the chairman at his meetings with Soviet leaders, translated Beijing’s bitter dispute with Moscow over ideological supremacy during the “Great Polemics China versus Soviet Union.” Yan told me, “I was at the table when the honeymoon turned into cold war.”

This is just his side in the life and suffering of the two Yan. Son Yan Mingfu 阎明复 and his father Yan Baohang 阎宝航 (1895 -1968) are the protagonists of a bizarre Chinese family saga. When the party accepted Yan Junior in 1949, he was unaware that his father and Christian educator had already been a member of the CP since 1937. But secretly, so no one would know, he was one of Mao’s top agents. The latter’s henchman Zhou Enlai had recruited him conspiratorially.

In his recently published book “Warlords” (Elfenbeinverlag, Berlin 2023), historian and sinologist Rainer Kloubert even calls Yan Baohang a “century spy.” Next to Richard Sorge – or even more than him – Yan became one of the most successful, but also most unknown agents of the 20th century.

Yan found his informants in Chongqing after the ruling Kuomintang party under Chiang Kai-shek made the Yangtze River city its temporary replacement capital after the Japanese invasion of China. As a staff aide to the legendary “young marshal” and warlord Zhang Xueliang, Yan also became acquainted with the Kuomintang elite, Chiang Kai-shek and his wife Soong Meiling. Soon after, he became general secretary for Chiang’s Christian-influenced “New Life” movement.

Yan was able to provide Mao with a steady stream of secrets from within the national government, including real scoops. For example, he obtained the date of Hitler’s plan to invade the Soviet Union in advance. In the week after June 20, 1941, he passed this information on to Mao, who dispatched it to Stalin on June 16. Stalin, as with Sorge, refused to acknowledge it, but thanked Mao in a secret telegram on June 30: “Thanks to your correct information, we were able to declare a state of alert for the Soviet Army before the German attack.”

Yan also informed Mao of Japan’s impending attack on Pearl Harbor in November 1941. The news was passed on to the USA via Stalin. The Kuomintang also informed the United States, but their reaction was also one of suspicion.

In his “Pictorial Arc of the Chinese Civil War,” which he devoted to the fascinating life story of warlord Zhang Xueliang, Kloubert traced the source of Yan’s predictions. Yan was friends with a “brilliant” Chinese mathematician named Chi Buzhou (池步洲). The latter was able to decipher Japan’s secret code in a cryptographic department set up by KMT intelligence chief Dai Li (戴笠) in Chongqing.

Even more important in late 1944 was Yan’s dispatch of exactly where and in what strength Japan’s Kwantung Army was positioned in northeast China. This helped Stalin’s Red Army to quickly defeat Japan’s forces. In 1995, Moscow posthumously awarded Yan Baohang a medal for this.

It was only after 1962 that Yan Baohang let his son in on his glorious double role. But then Mao’s revolution also ate its children; both Junior and Senior Yan fell victim to the chaos of the Cultural Revolution in 1967.

In 1967, the father was taken away first. Denounced as a Kuomintang reactionary, he was imprisoned in Beijing’s new Qincheng political prison, built with Soviet help. Ten days later, his son followed, accused of being a Soviet spy.

The son was imprisoned for seven and a half years, from 1967 to 1975. Only after his release was he told that his father had died in May 1968 – in Qincheng Prison, just a few meters away from him.

We – Ansa correspondent Barbara Alighiero and I – first learned this directly from Yan when we interviewed him in Beijing in September 1999. At the time, he wanted to remind us above all of his father’s achievements.

When I went to see Yan a second time with my wife Zhao Yuanhong in October 2002, we asked him to tell us the grotesque story in more detail. Yan began to tell it, but suddenly lost his composure and cried for minutes.

He was first interrogated by CC special investigators in November 1967, while he was head of the Russian interpreting department for Mao. Without any reason, they accused him of being a Soviet spy. On November 17, two soldiers dragged him before a gathering of 500 Red Guards, who shouted him down. A warrant was read to him and he was handcuffed. During the night, the henchmen took him to Qincheng. Yan was given the number 67124 as his new name. 67 stood for the year, 124 for the number of new prisoners brought in since the beginning of the year.

Ten days earlier, on November 7, his father had been abducted from his home. Again, no one knew where he was taken. Father Yan was also given a number: 67100. “We sat in solitary cells, not knowing about each other.” One day, someone had coughed in the outside corridor, just as his father did. “That’s impossible,” he thought at the time.

When Yan Mingfu was released in 1975, he was told that his father had served time near him and died on May 22, 1968. He later learned that Mao’s wife Jiang Qing, who controlled the detention lists, had ordered that the death of this “counterrevolutionary” not be reported nor his ashes kept. Yan’s Baohang’s wife knew neither where her husband nor her son was and died soon.

Free once again, Yan Mingfu made every effort to arrange a funeral for his father in Beijing’s Revolutionary Cemetery, partly as a sign of his public rehabilitation. It was held on January 5, 1978, ten years after he had passed away. Beijing limited the number of participants to 100 high-ranking mourners. “But more than 1,000 came,” he recalled.

In the hopeful reform era that followed, Yan climbed the party ladder and was allowed to edit a new “Great Encyclopedia” for China after Mao’s cultural cleansing, on which dozens of once-persecuted scholars collaborated.

In 1986, Yan was promoted to CC secretary and head of the Communist United Front. In May 1989, Deng Xiaoping brought him to Beijing for the historic reconciliation meeting with Soviet party leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Outside, tens of thousands of students demonstrated for greater freedom. At the request of Zhao Ziyang, the liberal party leader who was later overthrown, Yan attempted to mediate between the hunger strikers on Tiananmen Square and the hardliners in the Beijing leadership. He offered to join the students as a “hostage” to ensure that the party leadership met their demands.

Yan got caught between the fronts, failed to stop the massacre on June 4, 1989, and was stripped of all party posts a month later. But Deng did not abandon him completely. He allowed Yan to lead the Civil Affairs Ministry as vice chief after 1991 and found China’s Welfare Association (中华慈善总会). Online obituaries today call Yan the “father of China’s modern philanthropy” 中国现代慈善.

The bizarre saga of the two Yan does not find a happy ending in Xi Jinping’s China. Yan’s recent death was ignored by party officials. The news spread only on the Internet. The semi-official financial magazine Caixin was the only one allowed to publish a memorial essay by Deng Rong, Deng Xiaoping’s daughter.

Ten days after Yan’s death, the authorities finally allowed a funeral service to be held last Thursday. The party had previously settled on the lowest form of recognition of his merits in CP jargon. Yan had been an “outstanding party member and loyal communist fighter.”

Critical voices were excluded. The grand dame of Beijing’s dissidents, Gao Yu, tweeted that police officers lined up outside her apartment at six in the morning to prevent her from attending the funeral. She wrote: “We mourn him because during June 4, 1989, he wanted to solve the issue of the student movement under Zhao Ziyang’s ‘Way of Democracy and Law’.” 我們悼念他因為8964期間他執行趙紫陽的 “在民主與法制的道路上解決學運” Bloggers tried to bypass censorship for their online protests. Instead of forbidden words like “Yan and Tiananmen,” they wrote “person for dialogue on the square” 广场对话的人.

The saga of the two Yans does not fit in with today’s re-ideologized image of China, since the socialist history of the People’s Republic has been rewritten and glossed over and Mao’s crimes and the horrors of the Cultural Revolution relativized under Xi Jinping since 2017. That is Beijing’s problem with loyalist Yan Mingfu, especially after he published his two-volume memoirs in 2015. Nowadays, he would hardly get them past the censors. In 2015, renowned Chinese historians like Shen Zhihua or essayists like Ding Dong called the 1116 pages a treasure trove “of historical truth” and unadulterated history of the People’s Republic about the first 20 years of Sino-Soviet relations and the “Great Polemic” that almost resulted in war.

Yan writes, “It was a historical tragedy.” Mao had used it “as a prelude to his Cultural Revolution.” Yan describes Mao’s megalomania in his fight against Khrushchev with the words, “Who shall lead the socialist camp ideologically and that the east wind will defeat the west wind.” Reading between Yan’s lines today, one can’t help but think of Xi Jinping’s power fantasies.

Yan’s memoir tells many anecdotes, some with sarcastic punchlines. When Khrushchev announced in Beijing that he would increase the Soviet development aid projects for China that had been agreed upon for the first five-year plan (1953 to 1957), Yan wrote: “A special project then came along. Moscow wanted to help us build Qincheng Prison. Then during the Cultural Revolution, my father and I would end up there.”

Xiao Guo-Deters joined Cosco Shipping Europe this month as Manager of Strategy Development. Previously, she was Head of Marketing DACH Region for the Chinese private equity firm CS Capital, also in Hamburg.

Xindao Mao has moved to the post of Manager of Chromatography China at Sartorius Stedim Biotech in Shanghai. Previously, he worked for the same company, where he has been employed for almost four years, as Strategic Marketing Manager in Goettingen.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

The city of Shijiazhuang in the east of the country is not experiencing extreme temperatures like those in northwest China (see News). But with temperatures of 36 degrees, a little refreshment can’t hurt. These two at least seem to have no problem going home with soaking-wet clothes. But given the heat, they’ll probably be dry again by then anyway.