春节快乐! Today, the Year of the Rat ends and, at midnight, the Year of the Ox begins. The whole team of China.Table would like to wish you a happy new year. May you, your colleagues, your business partners and, of course, your family have a successful, happy and, above all, healthy new year.

One of the fascinations of the Chinese New Year is President Xi Jinping’s speech. Not so much because of Xi’s words, writes Johnny Erling in our festive edition. But because of the decoration of his study, which gives rise to the most exciting interpretations every year.

Are you perhaps – like Willy Brandt or Kate Moss – an ox? You will not only find information about this in our New Year glossary. Felix Lee has also dedicated a horoscope to the ox. And the whole team of China.Table compiles where the Chinese and expats can go in this pandemic year and with what kind of gifts they surprise their family members and friends.

The story of Ms. Mo is particularly moving. She is one of 300 million migrant workers, earns her living as a domestic helper in Beijing, and will not be able to visit her family for the New Year this year. Ning Wang spoke with Ms. Mo.

Perhaps you would like to surprise your family tonight with freshly prepared jiaozi? Yuhang Wu and Jonas Borchers run a small restaurant in Berlin. They cooked jiaozi for us and wrote down the recipe for you.

On behalf of the entire Table team, I wish you an enjoyable read – and don’t forget: Oxen should wear something red every day starting tomorrow to ward off bad luck.

Chinese consider themselves lucky because they can celebrate the New Year twice (with double the holiday entitlement). They look forward to the Western New Year on Dec. 31 and then to their traditional New Year and Family Festival (Chunjie), which begins on the night of Feb. 12 this year. But President Xi Jinping speaks to them directly only once – on Western New Year’s Day – via TV from his office in secretive Zhongnanhai – the party and government headquarters. His New Year’s speech is a classic in China.

How do you make sententious but boring New Year’s speeches interesting for viewers on TV? Chancellor Angela Merkel has not found a recipe yet. Newcomer Joe Biden did not knock anyone’s socks off with his first New Year’s speech either. According to polls, many of his viewers would have forgotten what he was talking about in the Oval Office barely ten minutes later.

Such worries are unknown to China’s President Xi Jinping. Ever since he gave his first New Year’s speech on New Year’s Eve in 2014, more and more Chinese people have been watching him every year – as they did during his 20-minute preface to 2021. Many even make a hobby of taking screenshots during the speech.

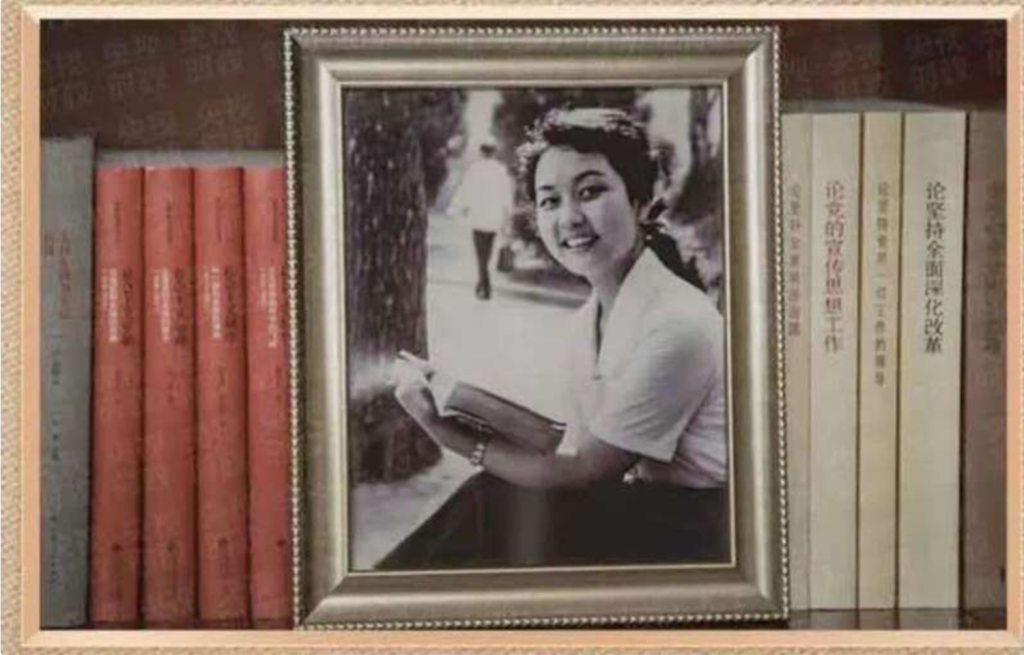

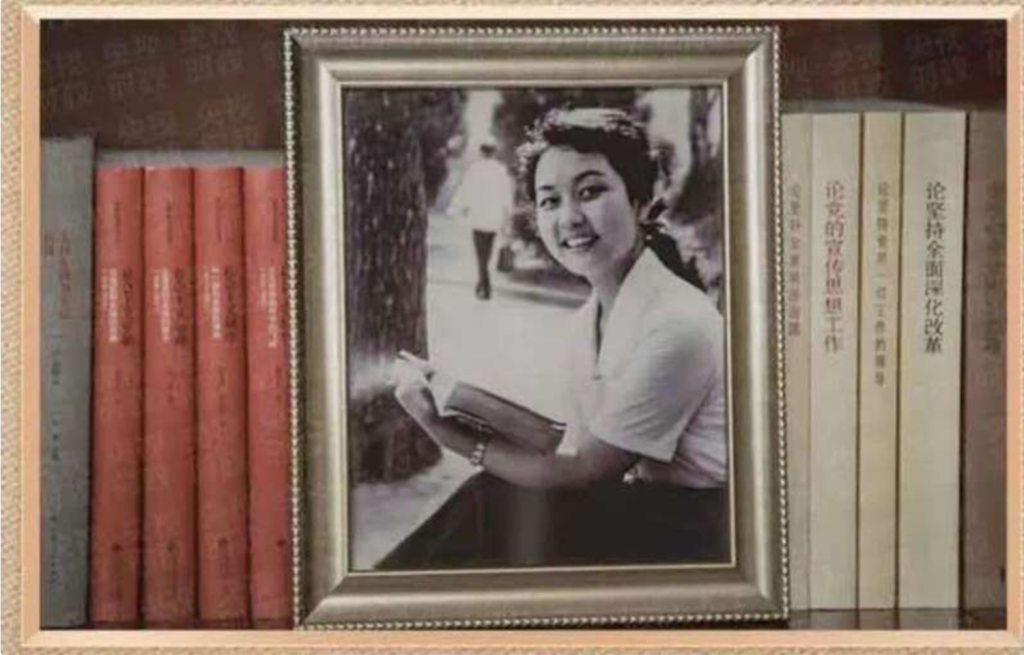

Their fascination has nothing to do with the content of his speech. President Xi only attracts so many viewers with his New Year‘s speech because they want to know what new items he has hidden for them on the bookshelves of his office. The TV cameras are helping them. With panning shots, they zoom into Xi’s impressive library. There, in front of the rows of books, are numerous family photos from the President’s private album. It is said that Xi chooses the pictures himself every year, and this strange curiosity has driven millions of Chinese to look for more photos of their ruler every New Year. The state press and social media do their best to fuel the hype.

Xi’s 2014 New Year’s speech was also the premiere of his office in the mysterious Zhongnanhai, which he presented to the public for the first time. The excitement grew when resourceful bloggers discovered six family photos on the shelves and took screenshots of them. The shots made headlines, showing China’s new ruler as a caring father riding his young daughter to school on a bicycle, a happy husband with his wife Peng Liyuan, a helpful son pushing his father, Xi Zhongxun, in a wheelchair. Party newspapers and social media promptly celebrated the new candor. Xi not only allowed citizens to look into his office as fence-sitters but also gave them a glimpse into his private life.

It did not stay long with the six family photos. A year later, in 2015, Xi surrounded himself with ten shots. Screenshots were not enough to identify them all. Party newspapers and websites worried about that. They published numbered photo way finders through Xi’s office, showing where and which images were on the shelves. They explained, for example, a photo showing Xi and his wife Peng visiting Berlin in March 2014. The couple is posing with young German-Chinese players after a friendly match between the junior team of VfL Wolfsburg and a youth team from Hubei and Shaanxi. Xi did not just put the picture in his office because he is a soccer fan. He demanded that the sport be introduced as a compulsory subject in China’s physical education classes. That is what happened next. China’s dream, which Xi propagates, also includes the Middle Kingdom kicking its way to the top of the FIFA world rankings.

It’s all calculation. Beijing controls and manages the insight it allows into Xi’s world of photos. It provides, as mockers say, transparency with Chinese characteristics. A public relations campaign is, above all, intended to put Xi in the right picture and, at the same time, promote his personality cult.

Blogger Zheng Zhijian, whose pseudonym is backed by the Communist Youth Newspaper, posted on his WeChat account all of this year’s photos set up in Xi’s office. He reported a new record of 21 shots. Thirteen of them are new photos. Most depict Xi as an exemplary family man, a man of the people, and a victor over the Covid pandemic. But two images also show him as a political strongman. One is from March 2018, when Xi took his oath of office on the constitution before the People’s Congress. Shortly before, Xi had managed to amend the constitution and remove the time limit for the office of president. From now on, he can rule indefinitely. The second photo shows him in December 2017, swearing allegiance to the Chinese Communist Party with a clenched fist at the Communist Party’s birthplace. Actually, he is swearing allegiance to himself. That’s because Xi previously got the party to change its bylaws to write his name and leadership role into it. The party has to follow Xi.

Critical observers noticed that six of the 21 New Year photos are portraits of Xi. For the first time, a youthful picture of his wife Peng is also included. In other pictures, both pose on an excursion in front of the ruins of the old summer palace, or the three of them rejoice with their baby. The impression of harmonious family life is deliberate. It is probably meant to dispel online rumors that the marriage is no longer on the best of terms.

Everything seems to have been thought of in the selection of the 21 private photos. Or is it? Katsuji Nakazawa, a longtime China correspondent for Japan’s Nikkei news agency, was puzzled over one shot. It shows Xi in 2020 inspecting southwest China’s Yunnan province. He stands amid laughing Wa minority girls and boys. The photo aims to highlight Xi’s successes in fighting poverty. In his New Year’s speech, Xi calls 2020 the year that brought him the “decisive victory” in his eight-year campaign to overcome extreme poverty in China. However, the Japanese journalist is only interested in the date under the photo: Jan. 19, 2020, when the Covid crisis in Wuhan escalated without Beijing pulling the emergency brake. Nagazawa researched that Xi was on a state visit to neighboring Myanmar on Jan. 17 and 18. On his way home, he would have stopped in Yunnan, 3,000 kilometers from Beijing, to spend the Spring Festival. He arrived back in Beijing on Jan. 21. It was not until Jan. 23 that Wuhan was completely sealed off. Had Xi and Beijing, contrary to their current protestations, reacted far too late and thus been partly responsible for the pandemic being on its way around the world?

Not only are the family photos selected with care, but the furnishings in Xi’s office are specially arranged. He sits demonstratively in front of two symbols of Chinese power, with the state flag behind him and an imposing painting of the Great Wall stretching across the mountains. His massive desk seems to date back to the time when IT high-tech and office electronics were not yet invented. There are no mobile phones, tablets, computers or mobile watches, which seems anachronistic, especially as Beijing has just reported that almost a billion Chinese will be using the internet by the end of 2020. Xi is presumably not allowed to show off his office hi-tech, lest the brands be recognized. On his desk is a compact conventional telephone system with three sets, two red and one white phone. According to Richard McGregor, author of the 2010 standard work “The Party”, they were once called the “red machines” and were part of an encrypted communications system. Only the highest functionaries and heads of the most important state-owned enterprises were connected to the party leaders via the phones. Xi has two red telephones at his disposal. Today, they probably only serve as status symbols.

His bamboo container full of sharpened pencils and crayons also dates from that time. Under Mao, party leaders used them to sign off documents as read with squiggles and to circulate them. A perforated calendar on the table, on which the last page of the year 2020 is open, looks even more like it was taken from a museum.

At the televised New Year’s address on Dec. 31 in the Oval Office, which Joe Biden delivered for the first time, no mobile phones were standing around on the table. Instead, there were two modern picture-sound phone systems next to him. US bloggers immediately took a virtual look around Biden’s office, describing his family photos, which he set up on a window ledge. Then they spied something old-fashioned like Xi’s punched-leaf calendar. In the middle of Biden’s desk was a wooden abacus, a Chinese mechanical calculating board. Perhaps it was meant as a sign for Xi?

Temple festivals have been canceled, as have New Year’s markets – China’s leadership has banned all events with large gatherings of people for the next few weeks for fear of new Covid outbreaks. No bustle, that’s the motto. According to popular wisdom, the New Year, which is welcomed on Friday night according to the lunar calendar, is actually a good one. The past year was that of the rat – it is considered wild and restless. And so was the year of the pandemic. 2021, on the other hand, is under the sign of the ox. And that promises to be more peaceful. In this respect, the canceled fairs are fitting: the prelude to a calmer year.

In Chinese astrology, each year is assigned to a particular animal in a twelve-year cycle: Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog and Pig. Both the people born in the corresponding year and the year itself are said to have the character traits of the respective animal. In China, the ox stands for patience and steadfastness. According to these character traits, the year will also be: gentle, without abrupt changes.

In terms of world politics, this forecast could be accurate: Trump was already voted out in the rat race – with Joe Biden as the new US President, calmer times are returning to Washington. And China’s Head of State and Party Leader, Xi Jinping, also seems to be opting for less aggressive tones when he calls for cooperation on the global pandemic, as he did most recently at the digital World Economic Forum in Davos. “We cannot tackle common challenges in a divided world,” he said in his speech. Verbally, at least, he is betting on more international understanding in the Year of the Ox. Xi, however, is not an ox according to the Chinese horoscope but was born in the Year of the Snake. And snakes are considered deceitful and not entirely honest. Oxen are afraid of them.

Whoever is born in the Year of the Ox is said to be diligent and persevering. The “ox” is also considered to be steady and reliable. The pursuit of fast money or a life beyond their means, however, is alien to it. Less willing to take risks, it prefers to follow well-trodden paths, as the saying goes. In relationships, oxen are said to be tender and loving. They are also said to be tolerant and balanced. They reject superficial talk and prefer the privacy of their own family. However, if they get too irritated, the harmless cattle can turn into dangerous bulls.

Each year of the zodiac is associated with one of the five elements: metal, wood, water, fire and earth. The year 2021 meets the element metal. So this Friday, approximately 1.5 billion Chinese worldwide welcome the Year of the Metal Ox. What additional benefits does the Year of the Ox bring when combined with the element of metal? More order in family life, say Chinese soothsayers. That certainly can’t hurt either after the exhausting lockdown Year of the Rat. Felix Lee

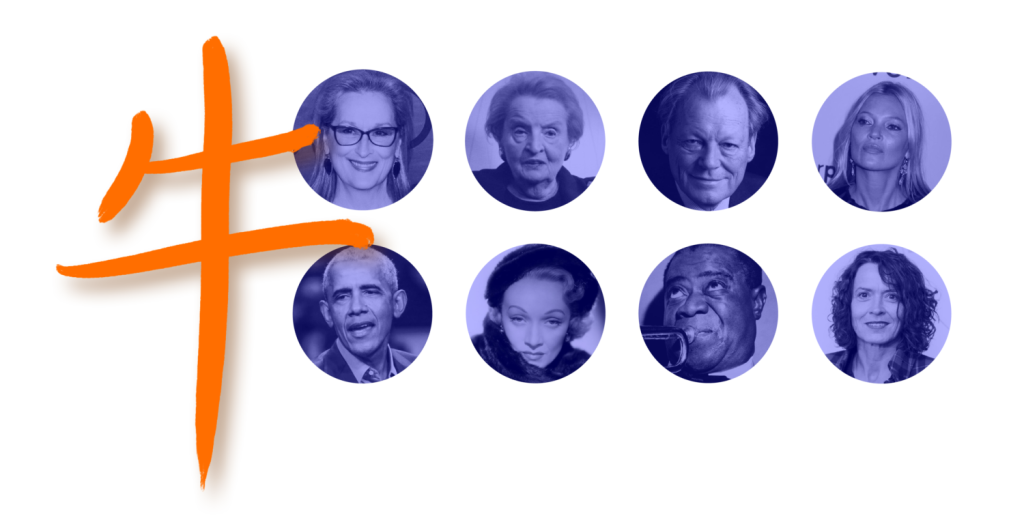

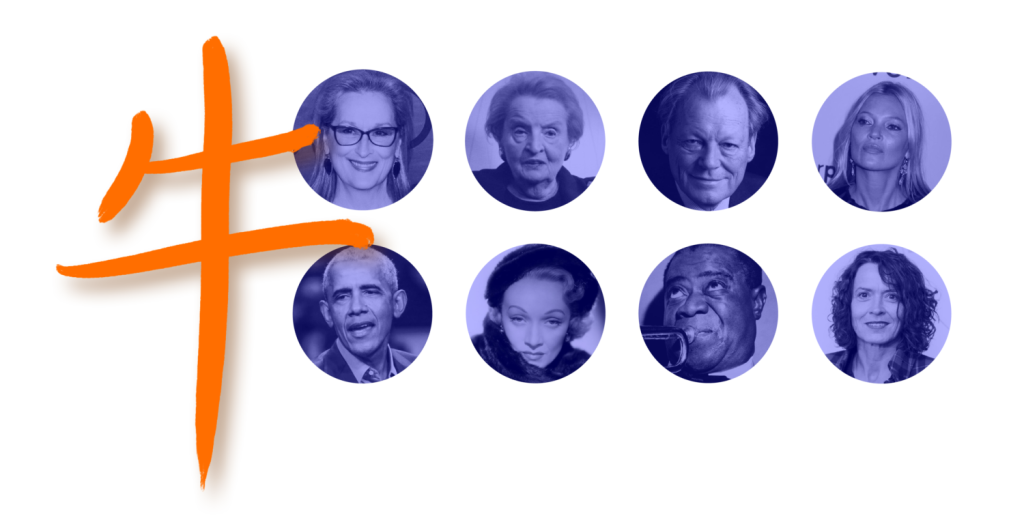

Every twelve years, the proud oxen are born. 1901 was a Year of the Ox, as were 1937, 1949, 1961, 1973, 1985, 1997 – and most recently 2009. And because the Chinese lunar year doesn’t quite fit the Western understanding of the “year” those born in January 1961, for example, are “not yet” oxen, whereas those born in January 1962 “still” are. Famous representatives of the zodiac sign include jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong (1901), German acting legend Marlene Dietrich (1901) as well as US politician Madeleine Albright (1937). Former US President Barack Obama (1961) is also an ox, as is Willy Brandt (1913) or the Princess of Wales, Diana Spencer (1961). But also the US actresses Jane Fonda (1937) and Meryl Streep (1949), the British model Kate Moss (1974), and the German actress Ulrike Folkerts (1961) are among them. Antje Sirleschtov

What the presents under the Christmas tree are for the Germans, the red envelope is for the Chinese at New Year. Weeks before China’s most important family festival, they are offered in all variations on the street, in department stores, and in supermarkets: Red envelopes folded from glossy paper, often decorated with a golden character that promises wealth, a long life, many children or simply good luck. These red envelopes (in Chinese: Hongbao) contain money.

A simple gesture, you might think. After all, everyone can use money. But far from it. Because who is the giver of these red envelopes and who is the recipient – that is complicated. The general rule is: anyone who is a child, student, pensioner, unmarried or unemployed can receive red envelopes. Those who earn money must give. And that is where the problem begins. Because especially for young professionals or newlyweds who do not yet earn that much or have put aside a lot of money, a spring party can quickly become a very expensive undertaking financially.

For children – even in the wider family – the giver puts between ¥100 and ¥200 in the red envelope, the equivalent of about €13 or €26. That is still within limits. But you also have to prepare such envelopes for your parents and grandparents – even if you were perhaps the recipient yourself a year or two earlier. Xiaoshun (孝顺), parental deference is expected. And this is measured not least in the amount of money that one puts into the envelope of one’s parents and grandparents as a son or daughter. In today’s times, this can quickly be ¥500, ¥1000 or ¥2000.

The handover is even more complicated. Of course, parents, grandparents, but also aunts and uncles politely but vehemently reject the red envelopes at first. At least that is what they suggest when they try to put the envelopes in your hand or pocket with their hands flailing. The giver then has to push all the more insistently for them to accept the envelopes. This then goes back and forth. Until they finally accept the envelope.

And do not be surprised if children show little enthusiasm, despite the gifts of money. Their parents do make them politely thank their uncle or cousin. But often, they do not get the money at all – because the envelopes are pocketed by the parents. After all, they are the ones who have to stuff the envelopes for others. Felix Lee

For Ms. Mo, 2020 was a bad year financially: First, because of Covid-related travel restrictions, she was unable to return to Beijing, where she works as a domestic helper for Chinese families, earning around €600 a month. Then, when she finally arrived back in Beijing in April, many jobs disappeared. She had to draw on her savings and is happy to say that she now earns almost as much as she did before the Covid pandemic broke out. “I’m definitely not going home for Chunjie this year,” she says. Too great is the fear of not returning in time again and losing jobs.

300 million migrant workers in China often feel like second-class citizens because China’s hukou system blocks their access to health care, education for their children or affordable housing. China’s hukou system provides social benefits to citizens only in the places where they were born. Official data show that the number of migrant workers fell by 5.2 million in 2020 compared to the previous year.

The possibility of going home was already taken away from many migrant workers in mid-January. Because by then, at the latest, they would have had to be tested to be able to take part in the celebrations for the Chinese New Year. Many are already going home at the end of January. However, the Chinese National Health Commission had ordered that people returning to rural areas must present a negative Covid-19 test not older than seven days.

For many migrant workers like Ms. Mo, who can only take two to three weeks off at a time once a year, going home would also have meant a double quarantine – first in her home country, then in Beijing on her return.

But there are also incentives not to go home. The city of Hangzhou has promised migrant workers ¥1000 (€125) if they do not go home. Companies in Zhejiang or Ningbo also pay cash bonuses to give employees an incentive to stay. The companies’ order books are full. It suits them just fine that migrant workers cannot travel. Some cities also grant migrant workers additional privileges over the holidays, for example, in the health sector.

Still, it is hard for Ms. Mo. She has a ten-year-old son at home, and her parents take care of him all year round. She talks to him on the phone via WeChat’s video function every evening, usually while she is doing the dishes in one of the households where she works. Often the topics of conversation are the same: “Did you do your homework?” she asks him. “When are you going to write your next paper at school? Study hard and I’ll buy you something nice when I come to visit.” But this year, she will only be able to mail him the Chinese New Year gifts. She does not know when she can see him next. The next holiday – the Ancestor’s Memorial Festival from April 3-5 – is too short for the more than ten-hour train ride. Ning Wang

In recent years, the period around Chinese New Year has been one thing above all: travel time. Hundreds of millions of Chinese set off in the weeks before and after the holiday to visit their families in their home villages or to travel abroad. Because so many people were on the move at the same time in a short period, this period is also known as the world’s largest annual migration. This year is different. The Bloomberg news agency has calculated that in average years, Chinese airlines make up to a quarter of their annual profits around the CNY.

More than a year after the start of the pandemic, the Chinese leadership has called on its citizens not to go home or make any other journey for what should be the most important family festival. “Stay where you are!” is the government’s slogan. Yet it has largely contained the spread of the virus. Although there are still isolated outbreaks, the authorities are taking rigid action. Neighborhoods are sealed off completely, entire cities of millions have to be tested as soon as only a few dozen cases occur in one place. Travel has already decreased by around a third compared to previous years.

There is no explicit travel ban – but anyone traveling should have a negative Covid test with them. Of course, masks must be worn on all public transport, including planes and high-speed trains. In addition, the health app on the smartphone must be working: At the entrance to the airport or train station, you’ll be asked to open your “Health Status Quary System” app in WeChat to scan the QR code. You can enter the building when your picture and the sentence “no abnormal conditions” appear.

If you already have them, it is also possible to save the Covid test and the vaccination in the app. Vaccinations are currently not mandatory. The phone and passport numbers are stored in the app so that the authorities can inform people if they have been in the vicinity of a person suffering from Covid. Frank Sieren/Felix Lee

In normal years, many foreigners leave China to escape the wave of travel within the People’s Republic. For them, Chinese New Year is less of a holiday and more of a good opportunity for a short vacation. In major cities, many restaurants and smaller shops are closed over the holidays as employees head home. Expats in China then like to use the time for a few days in the sun – for example, in Thailand, Vietnam or on the island of Boracay, the Mallorca of the Philippines. Others decide to go skiing, to the north of South Korea or to Japan, where there are large ski resorts with hot springs.

This year, however, that is not possible: Three weeks of quarantine on return are too big a hurdle. Most expats are therefore staying at home this year and, at most, making excursions into the surrounding area – such as hiking the Great Wall, to the icy waterfalls, and to Nanshan, a small ski resort in Beijing’s Miyun district.

Those who can’t stand being out of the sun will also find a destination within China: some fly to the tropical island of Hainan, about a three-and-a-half-hour flight from Beijing. Daytime temperatures there are currently 25 degrees and the water is 23 degrees – in Beijing, on the other hand, temperatures currently hover between plus five and minus five degrees. For Hainan, however, tourists need a Covid test for both the outward and return journey. However, several travelers have already described that they did not have to show a test, at least when entering the island.

There are stricter controls when traveling to larger ski resorts within China: The ski regions are about a three-hour drive north of Beijing around the city of Chongli. The Winter Olympics are to be held there in a year. Temperatures can sometimes drop below minus 30 degrees.

Some expats, especially study abroad students who do not have family in China, are also invited home by their Chinese friends – which is considered a sign of great friendship. For those who are not going away and not looking for a Chinese family connection, some Beijing and Shanghai clubs and pubs have prepared CNY parties that closely resemble Western celebrations on New Year’s Eve. Frank Sieren

It will stay quiet in the Chinese capital for the CNY: The last time, the rules for New Year’s fireworks were tightened in December 2017 – since then, it is no longer allowed to set off fireworks within the 5th ring. The official reason given at the time was mainly air pollution. But the danger of the firecrackers also played a role: In February 2009, for example, a new, fortunately still uninhabited high-rise building went up in flames after a fireworks display in Beijing’s Central Business District. After that, fireworks were only allowed to be set off in Beijing’s city center in certain designated places. Eight years later, a complete ban was enforced. This year, however, the central official fireworks displays were also canceled in many cities.

The fireworks in Hong Kong are considered the most spectacular in China. It is set off in Victoria Harbour, the strait between Hong Kong Island and the mainland of Kowloon. Hundreds of thousands usually gather to see it. Hundreds of ships with onlookers anchor in the strait. In 2021, however, the fireworks are canceled due to Covid.

Traditionally, it is customary to launch fireworks not only at midnight – but every evening for at least the first three days of the Chinese New Year. Superstition has it that the louder the fireworks, the better the business and the harvest. Therefore, private fireworks, unlike official fireworks, are not particularly colorful but particularly loud.

The first fireworks also had no great light effects. They were pieces of bamboo filled with gunpowder that were thrown into the fire and then exploded. This is where the name Baozhu comes from: “exploding bamboo”. This happened 200 years before Christ in the city of Liuyang. Even today, the city of 1.5 million people in the southeast Chinese province of Hunan is the capital of fireworks production.

China produces around 90 percent of the world’s fireworks. 60 percent of them are produced in Liuyang. It is mostly women who produce them – a very dangerous profession. According to estimates by the Chinese Workplace Safety Administration, only coal mine work is more dangerous. In the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD), people started to wrap the firecrackers in lucky red paper.

For the superstitious, it is important to leave the red paper lying around after the explosion – so as not to sweep away good luck. Until a few years ago, downtown Beijing was littered with red paper scraps when the clouds from the explosions had cleared. In villages in the countryside, this is still the case today. Traditionally, smaller fireworks are set off before the New Year’s Eve dinner to invite in the ancestors, and then the main fireworks are set off at midnight to drive away evil spirits. The last chance to set off fireworks is at the Lantern Festival, which takes place 14 days after the Chinese New Year. Frank Sieren

Not only do red envelopes change hands on New Year’s Day, but products with the celebrated sign of the zodiac are also a welcome gift. From luxury labels to sports outfits and tech companies, the ox can also be found on clothing, accessories and even headphones designed especially for the CNY. European brands such as Burberry and Louis Vuitton (LV) present so-called capsule collections for the Chinese New Year. LV is offering scarves with a logo and a cartoon ox or leather key rings, among other things. British label Burberry is offering jackets and bags with the usual check pattern and ox head – customers can also buy a peaked cap with small ox horns sticking out. Nike is selling a CNY shoe with an ox print and a red cord.

Danish toy manufacturer Lego is offering a kit for a bovine made of Lego bricks for the Year of the Ox. Barbie maker Mattel is releasing a version of the doll in traditional qipao for the CNY celebrations. Tech giant Apple is offering limited edition headphones emblazoned with an ox figurine on their storage box, as well as several mugs, T-shirts and chopsticks with zodiac imprints. Traditionally, the new year should also begin with a new outfit, which is why clothing – with or without an ox – is a welcome gift, preferably in the lucky color of red. Amelie Richter

In the week before the Chinese New Year, decorations in the form of red lanterns, banners or New Year silhouettes are hung on the door frame, spring cleaning is done – and above all, tons of food are bought. New Year’s Eve also includes the New Year’s Eve feast, when the whole family gathers around the table. In addition to the jiaozis, these dishes belong on the New Year’s table, which not only provide for physical well-being but, above all, symbolically bring long life, harmony, prosperity and luck:

Fish: A whole fish belongs on the table. The word fish 鱼 (yú) is the same as the word for surplus. But be careful not to “flip” the fish, or the surplus will be reversed. And there must be leftovers from the fish to demonstrate that everything is abundant.

Long (living) noodles: “Longevity noodles” (cháng shòu miàn, 长寿面) are very popular, also for birthdays. The longer the noodles, the longer you live. Therefore, they won’t be broken when they are cooked, for example, because the pot is too small.

Chicken: Similar to the whole fish, the whole chicken serves as a symbol of unity. The chicken (zhěng jī,整鸡) is served whole, that is, with head and feet.

Mandarins/oranges (júzi, 桔子): The yellow-orange color of these fruits is associated with good luck, and depending on the Chinese dialect, the names of the fruits sound like “luck”. Fruits with leaves are especially popular for Chinese New Year, as they symbolize longevity.

Niangao: Another must-try is niangao (年糕, also known as Chinese New Year cake), which sounds like 年高, which means “higher year” or – more grammatically accurate – an “increasingly successful year.” Variations vary from region to region; while niangao in the north likes to be steamed into a round cake, it is also served hearty with pork in the Shanghai region.

Tangyuan (汤圆) are balls of glutinous rice flour cooked and served in a lightly sweetened soup. They can be large and filled (with sesame, peanut or red bean paste) or small and unfilled. They are eaten on the first full moon after the Chinese New Year for the Lantern Festival.

Sweets: Oh yes, sweets are definitely a must, not only for the kids to stay up late and scare away the New Year’s monster, but especially to sweeten life in the New Year as well. Ning Wang

To welcome the Year of the Ox, millions of dumplings are consumed at dining tables in China today. In northern China, in particular, jiaozi is simply part of the New Year. Since their shape resembles small gold bars used as currency in imperial times, they promise good luck and prosperity. Especially when you find the one coin hidden in a dumpling during the traditional New Year feast. Apart from small change, the dumplings are filled with anything that tastes good: pork, shrimp, Chinese leek, beef or mutton, fried egg, carrots, eggplant, fennel greens and shepherd’s purse are also popular. Even jiaozi with cheese or chocolate filling can be found. When the whole family gets involved, the jiaozi production is at least as much fun as the food itself. Why don’t you give it a try? Chef Yuhang Wu provides the recipe.

Ingredients (serves 4):

Dough:

500g flour

250ml water

3g salt

Filling:

15g ginger

15g leek

2g Sichuan pepper

150ml boiling water

300g organic pork mince

500g Chinese cabbage, finely chopped

3 tbsp light soy sauce

1 tbsp dark soy sauce

1 tbsp oyster sauce

3 tsp salt

1 tsp sugar

4 tbsp sesame oil

Preparation:

The secret of this jiaozi recipe is the spice infusion of ginger, leek and Sichuan pepper. It gives the filling its flavor. Simply pour boiling water over the coarsely chopped ingredients and leave to infuse for 20 minutes.

Then wash the Chinese cabbage thoroughly, cut it into very fine cubes, add 1 tsp salt, mix thoroughly and set aside so that the salt can remove the water from the cabbage.

Dough:

In a large bowl, mix flour with salt. Gradually add water, using two chopsticks to mix with the flour. When all the flour is combined, keep pressing down and folding the dough with a clenched fist until it forms a mass. Knead this mass until it is smooth and malleable. Then cover with cling film and set aside.

Filling:

Wring out the finely minced Chinese cabbage with your hands; the drier the better. While stirring, pour the cooled spice infusion through a sieve and gradually add the liquid to the minced pork. Stirring works best with two chopsticks held in one hand. Keep stirring in one direction until the meat completely absorbs the spice infusion. This may take up to five minutes. Then add light and dark soy sauce, oyster sauce, salt and sugar and continue stirring until these ingredients have also combined completely with the meat mixture. Only now the sesame oil is added and stirred thoroughly with the meat mixture. Finally, add the finely minced Chinese cabbage, as dry as possible. Stir one last time until you have an even filling that is firm enough to stick a chopstick in.

Roll out…

Now the grand finale begins. Cut the dough into four equal, elongated pieces and form each of them into an approx. 2cm thick dough roll by hand. From this roll, cut 20 equal pieces of about 10g each with the knife or dough scraper and turn them in flour so they will not stick. Flatten each piece by hand with the cut side on top. Roll out the slices to about the size of the palm of your hand. In China, a small rolling pin is used for this purpose, but a large rolling pin or a clean glass bottle can also be used. Professionals manage to make the dough slices a little thinner at the edges than in the middle. Cover the rolled-out dough patties with cling film until you are ready to fill them.

…fill…

Place one dough patty at a time on the palm of your hand, spread about a tablespoon of the filling in the middle, and then fold the upper edge upwards to form a small half-moon. Closing the jiaozi requires a little practice but is not that difficult if you follow a few rules: Do not use too much filling and only spread it in the middle; after the folding, first press the two halves together only in the middle of the edge and only then both sides. Place the finished jiaozi on a well-floured surface so that they do not stick.

…and cook

Bring unsalted water to a boil in a large pot and carefully add the jiaozi. Then stir gently with a ladle so that no jiaozi stick to the bottom of the pot. After a few minutes, the jiaozi will float to the surface. Now add another 50ml of cold water, wait until the water boils and add another 50ml or so of cold water. When the water boils bubbly for the third time, the jiaozi are ready and can be ladled onto the plate. Jiaozi taste best when dipped in a dip of soy sauce, black vinegar and a little chili oil. Yuhang Wu / Jonas Borchers

Bon appetit and good luck and wealth in the new Year of the Ox!

Yuhang Wu and Jonas Borchers opened their restaurant UUU in Berlin-Wedding in September 2020. Previously, Wu worked in the country’s best Michelin-starred kitchens. Together with their guests, they want to rediscover Chinese cuisine at UUU. You can order the jiaozi at the online shop of their restaurant UUU: uuu-berlin.de/athome/

春节快乐! Today, the Year of the Rat ends and, at midnight, the Year of the Ox begins. The whole team of China.Table would like to wish you a happy new year. May you, your colleagues, your business partners and, of course, your family have a successful, happy and, above all, healthy new year.

One of the fascinations of the Chinese New Year is President Xi Jinping’s speech. Not so much because of Xi’s words, writes Johnny Erling in our festive edition. But because of the decoration of his study, which gives rise to the most exciting interpretations every year.

Are you perhaps – like Willy Brandt or Kate Moss – an ox? You will not only find information about this in our New Year glossary. Felix Lee has also dedicated a horoscope to the ox. And the whole team of China.Table compiles where the Chinese and expats can go in this pandemic year and with what kind of gifts they surprise their family members and friends.

The story of Ms. Mo is particularly moving. She is one of 300 million migrant workers, earns her living as a domestic helper in Beijing, and will not be able to visit her family for the New Year this year. Ning Wang spoke with Ms. Mo.

Perhaps you would like to surprise your family tonight with freshly prepared jiaozi? Yuhang Wu and Jonas Borchers run a small restaurant in Berlin. They cooked jiaozi for us and wrote down the recipe for you.

On behalf of the entire Table team, I wish you an enjoyable read – and don’t forget: Oxen should wear something red every day starting tomorrow to ward off bad luck.

Chinese consider themselves lucky because they can celebrate the New Year twice (with double the holiday entitlement). They look forward to the Western New Year on Dec. 31 and then to their traditional New Year and Family Festival (Chunjie), which begins on the night of Feb. 12 this year. But President Xi Jinping speaks to them directly only once – on Western New Year’s Day – via TV from his office in secretive Zhongnanhai – the party and government headquarters. His New Year’s speech is a classic in China.

How do you make sententious but boring New Year’s speeches interesting for viewers on TV? Chancellor Angela Merkel has not found a recipe yet. Newcomer Joe Biden did not knock anyone’s socks off with his first New Year’s speech either. According to polls, many of his viewers would have forgotten what he was talking about in the Oval Office barely ten minutes later.

Such worries are unknown to China’s President Xi Jinping. Ever since he gave his first New Year’s speech on New Year’s Eve in 2014, more and more Chinese people have been watching him every year – as they did during his 20-minute preface to 2021. Many even make a hobby of taking screenshots during the speech.

Their fascination has nothing to do with the content of his speech. President Xi only attracts so many viewers with his New Year‘s speech because they want to know what new items he has hidden for them on the bookshelves of his office. The TV cameras are helping them. With panning shots, they zoom into Xi’s impressive library. There, in front of the rows of books, are numerous family photos from the President’s private album. It is said that Xi chooses the pictures himself every year, and this strange curiosity has driven millions of Chinese to look for more photos of their ruler every New Year. The state press and social media do their best to fuel the hype.

Xi’s 2014 New Year’s speech was also the premiere of his office in the mysterious Zhongnanhai, which he presented to the public for the first time. The excitement grew when resourceful bloggers discovered six family photos on the shelves and took screenshots of them. The shots made headlines, showing China’s new ruler as a caring father riding his young daughter to school on a bicycle, a happy husband with his wife Peng Liyuan, a helpful son pushing his father, Xi Zhongxun, in a wheelchair. Party newspapers and social media promptly celebrated the new candor. Xi not only allowed citizens to look into his office as fence-sitters but also gave them a glimpse into his private life.

It did not stay long with the six family photos. A year later, in 2015, Xi surrounded himself with ten shots. Screenshots were not enough to identify them all. Party newspapers and websites worried about that. They published numbered photo way finders through Xi’s office, showing where and which images were on the shelves. They explained, for example, a photo showing Xi and his wife Peng visiting Berlin in March 2014. The couple is posing with young German-Chinese players after a friendly match between the junior team of VfL Wolfsburg and a youth team from Hubei and Shaanxi. Xi did not just put the picture in his office because he is a soccer fan. He demanded that the sport be introduced as a compulsory subject in China’s physical education classes. That is what happened next. China’s dream, which Xi propagates, also includes the Middle Kingdom kicking its way to the top of the FIFA world rankings.

It’s all calculation. Beijing controls and manages the insight it allows into Xi’s world of photos. It provides, as mockers say, transparency with Chinese characteristics. A public relations campaign is, above all, intended to put Xi in the right picture and, at the same time, promote his personality cult.

Blogger Zheng Zhijian, whose pseudonym is backed by the Communist Youth Newspaper, posted on his WeChat account all of this year’s photos set up in Xi’s office. He reported a new record of 21 shots. Thirteen of them are new photos. Most depict Xi as an exemplary family man, a man of the people, and a victor over the Covid pandemic. But two images also show him as a political strongman. One is from March 2018, when Xi took his oath of office on the constitution before the People’s Congress. Shortly before, Xi had managed to amend the constitution and remove the time limit for the office of president. From now on, he can rule indefinitely. The second photo shows him in December 2017, swearing allegiance to the Chinese Communist Party with a clenched fist at the Communist Party’s birthplace. Actually, he is swearing allegiance to himself. That’s because Xi previously got the party to change its bylaws to write his name and leadership role into it. The party has to follow Xi.

Critical observers noticed that six of the 21 New Year photos are portraits of Xi. For the first time, a youthful picture of his wife Peng is also included. In other pictures, both pose on an excursion in front of the ruins of the old summer palace, or the three of them rejoice with their baby. The impression of harmonious family life is deliberate. It is probably meant to dispel online rumors that the marriage is no longer on the best of terms.

Everything seems to have been thought of in the selection of the 21 private photos. Or is it? Katsuji Nakazawa, a longtime China correspondent for Japan’s Nikkei news agency, was puzzled over one shot. It shows Xi in 2020 inspecting southwest China’s Yunnan province. He stands amid laughing Wa minority girls and boys. The photo aims to highlight Xi’s successes in fighting poverty. In his New Year’s speech, Xi calls 2020 the year that brought him the “decisive victory” in his eight-year campaign to overcome extreme poverty in China. However, the Japanese journalist is only interested in the date under the photo: Jan. 19, 2020, when the Covid crisis in Wuhan escalated without Beijing pulling the emergency brake. Nagazawa researched that Xi was on a state visit to neighboring Myanmar on Jan. 17 and 18. On his way home, he would have stopped in Yunnan, 3,000 kilometers from Beijing, to spend the Spring Festival. He arrived back in Beijing on Jan. 21. It was not until Jan. 23 that Wuhan was completely sealed off. Had Xi and Beijing, contrary to their current protestations, reacted far too late and thus been partly responsible for the pandemic being on its way around the world?

Not only are the family photos selected with care, but the furnishings in Xi’s office are specially arranged. He sits demonstratively in front of two symbols of Chinese power, with the state flag behind him and an imposing painting of the Great Wall stretching across the mountains. His massive desk seems to date back to the time when IT high-tech and office electronics were not yet invented. There are no mobile phones, tablets, computers or mobile watches, which seems anachronistic, especially as Beijing has just reported that almost a billion Chinese will be using the internet by the end of 2020. Xi is presumably not allowed to show off his office hi-tech, lest the brands be recognized. On his desk is a compact conventional telephone system with three sets, two red and one white phone. According to Richard McGregor, author of the 2010 standard work “The Party”, they were once called the “red machines” and were part of an encrypted communications system. Only the highest functionaries and heads of the most important state-owned enterprises were connected to the party leaders via the phones. Xi has two red telephones at his disposal. Today, they probably only serve as status symbols.

His bamboo container full of sharpened pencils and crayons also dates from that time. Under Mao, party leaders used them to sign off documents as read with squiggles and to circulate them. A perforated calendar on the table, on which the last page of the year 2020 is open, looks even more like it was taken from a museum.

At the televised New Year’s address on Dec. 31 in the Oval Office, which Joe Biden delivered for the first time, no mobile phones were standing around on the table. Instead, there were two modern picture-sound phone systems next to him. US bloggers immediately took a virtual look around Biden’s office, describing his family photos, which he set up on a window ledge. Then they spied something old-fashioned like Xi’s punched-leaf calendar. In the middle of Biden’s desk was a wooden abacus, a Chinese mechanical calculating board. Perhaps it was meant as a sign for Xi?

Temple festivals have been canceled, as have New Year’s markets – China’s leadership has banned all events with large gatherings of people for the next few weeks for fear of new Covid outbreaks. No bustle, that’s the motto. According to popular wisdom, the New Year, which is welcomed on Friday night according to the lunar calendar, is actually a good one. The past year was that of the rat – it is considered wild and restless. And so was the year of the pandemic. 2021, on the other hand, is under the sign of the ox. And that promises to be more peaceful. In this respect, the canceled fairs are fitting: the prelude to a calmer year.

In Chinese astrology, each year is assigned to a particular animal in a twelve-year cycle: Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog and Pig. Both the people born in the corresponding year and the year itself are said to have the character traits of the respective animal. In China, the ox stands for patience and steadfastness. According to these character traits, the year will also be: gentle, without abrupt changes.

In terms of world politics, this forecast could be accurate: Trump was already voted out in the rat race – with Joe Biden as the new US President, calmer times are returning to Washington. And China’s Head of State and Party Leader, Xi Jinping, also seems to be opting for less aggressive tones when he calls for cooperation on the global pandemic, as he did most recently at the digital World Economic Forum in Davos. “We cannot tackle common challenges in a divided world,” he said in his speech. Verbally, at least, he is betting on more international understanding in the Year of the Ox. Xi, however, is not an ox according to the Chinese horoscope but was born in the Year of the Snake. And snakes are considered deceitful and not entirely honest. Oxen are afraid of them.

Whoever is born in the Year of the Ox is said to be diligent and persevering. The “ox” is also considered to be steady and reliable. The pursuit of fast money or a life beyond their means, however, is alien to it. Less willing to take risks, it prefers to follow well-trodden paths, as the saying goes. In relationships, oxen are said to be tender and loving. They are also said to be tolerant and balanced. They reject superficial talk and prefer the privacy of their own family. However, if they get too irritated, the harmless cattle can turn into dangerous bulls.

Each year of the zodiac is associated with one of the five elements: metal, wood, water, fire and earth. The year 2021 meets the element metal. So this Friday, approximately 1.5 billion Chinese worldwide welcome the Year of the Metal Ox. What additional benefits does the Year of the Ox bring when combined with the element of metal? More order in family life, say Chinese soothsayers. That certainly can’t hurt either after the exhausting lockdown Year of the Rat. Felix Lee

Every twelve years, the proud oxen are born. 1901 was a Year of the Ox, as were 1937, 1949, 1961, 1973, 1985, 1997 – and most recently 2009. And because the Chinese lunar year doesn’t quite fit the Western understanding of the “year” those born in January 1961, for example, are “not yet” oxen, whereas those born in January 1962 “still” are. Famous representatives of the zodiac sign include jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong (1901), German acting legend Marlene Dietrich (1901) as well as US politician Madeleine Albright (1937). Former US President Barack Obama (1961) is also an ox, as is Willy Brandt (1913) or the Princess of Wales, Diana Spencer (1961). But also the US actresses Jane Fonda (1937) and Meryl Streep (1949), the British model Kate Moss (1974), and the German actress Ulrike Folkerts (1961) are among them. Antje Sirleschtov

What the presents under the Christmas tree are for the Germans, the red envelope is for the Chinese at New Year. Weeks before China’s most important family festival, they are offered in all variations on the street, in department stores, and in supermarkets: Red envelopes folded from glossy paper, often decorated with a golden character that promises wealth, a long life, many children or simply good luck. These red envelopes (in Chinese: Hongbao) contain money.

A simple gesture, you might think. After all, everyone can use money. But far from it. Because who is the giver of these red envelopes and who is the recipient – that is complicated. The general rule is: anyone who is a child, student, pensioner, unmarried or unemployed can receive red envelopes. Those who earn money must give. And that is where the problem begins. Because especially for young professionals or newlyweds who do not yet earn that much or have put aside a lot of money, a spring party can quickly become a very expensive undertaking financially.

For children – even in the wider family – the giver puts between ¥100 and ¥200 in the red envelope, the equivalent of about €13 or €26. That is still within limits. But you also have to prepare such envelopes for your parents and grandparents – even if you were perhaps the recipient yourself a year or two earlier. Xiaoshun (孝顺), parental deference is expected. And this is measured not least in the amount of money that one puts into the envelope of one’s parents and grandparents as a son or daughter. In today’s times, this can quickly be ¥500, ¥1000 or ¥2000.

The handover is even more complicated. Of course, parents, grandparents, but also aunts and uncles politely but vehemently reject the red envelopes at first. At least that is what they suggest when they try to put the envelopes in your hand or pocket with their hands flailing. The giver then has to push all the more insistently for them to accept the envelopes. This then goes back and forth. Until they finally accept the envelope.

And do not be surprised if children show little enthusiasm, despite the gifts of money. Their parents do make them politely thank their uncle or cousin. But often, they do not get the money at all – because the envelopes are pocketed by the parents. After all, they are the ones who have to stuff the envelopes for others. Felix Lee

For Ms. Mo, 2020 was a bad year financially: First, because of Covid-related travel restrictions, she was unable to return to Beijing, where she works as a domestic helper for Chinese families, earning around €600 a month. Then, when she finally arrived back in Beijing in April, many jobs disappeared. She had to draw on her savings and is happy to say that she now earns almost as much as she did before the Covid pandemic broke out. “I’m definitely not going home for Chunjie this year,” she says. Too great is the fear of not returning in time again and losing jobs.

300 million migrant workers in China often feel like second-class citizens because China’s hukou system blocks their access to health care, education for their children or affordable housing. China’s hukou system provides social benefits to citizens only in the places where they were born. Official data show that the number of migrant workers fell by 5.2 million in 2020 compared to the previous year.

The possibility of going home was already taken away from many migrant workers in mid-January. Because by then, at the latest, they would have had to be tested to be able to take part in the celebrations for the Chinese New Year. Many are already going home at the end of January. However, the Chinese National Health Commission had ordered that people returning to rural areas must present a negative Covid-19 test not older than seven days.

For many migrant workers like Ms. Mo, who can only take two to three weeks off at a time once a year, going home would also have meant a double quarantine – first in her home country, then in Beijing on her return.

But there are also incentives not to go home. The city of Hangzhou has promised migrant workers ¥1000 (€125) if they do not go home. Companies in Zhejiang or Ningbo also pay cash bonuses to give employees an incentive to stay. The companies’ order books are full. It suits them just fine that migrant workers cannot travel. Some cities also grant migrant workers additional privileges over the holidays, for example, in the health sector.

Still, it is hard for Ms. Mo. She has a ten-year-old son at home, and her parents take care of him all year round. She talks to him on the phone via WeChat’s video function every evening, usually while she is doing the dishes in one of the households where she works. Often the topics of conversation are the same: “Did you do your homework?” she asks him. “When are you going to write your next paper at school? Study hard and I’ll buy you something nice when I come to visit.” But this year, she will only be able to mail him the Chinese New Year gifts. She does not know when she can see him next. The next holiday – the Ancestor’s Memorial Festival from April 3-5 – is too short for the more than ten-hour train ride. Ning Wang

In recent years, the period around Chinese New Year has been one thing above all: travel time. Hundreds of millions of Chinese set off in the weeks before and after the holiday to visit their families in their home villages or to travel abroad. Because so many people were on the move at the same time in a short period, this period is also known as the world’s largest annual migration. This year is different. The Bloomberg news agency has calculated that in average years, Chinese airlines make up to a quarter of their annual profits around the CNY.

More than a year after the start of the pandemic, the Chinese leadership has called on its citizens not to go home or make any other journey for what should be the most important family festival. “Stay where you are!” is the government’s slogan. Yet it has largely contained the spread of the virus. Although there are still isolated outbreaks, the authorities are taking rigid action. Neighborhoods are sealed off completely, entire cities of millions have to be tested as soon as only a few dozen cases occur in one place. Travel has already decreased by around a third compared to previous years.

There is no explicit travel ban – but anyone traveling should have a negative Covid test with them. Of course, masks must be worn on all public transport, including planes and high-speed trains. In addition, the health app on the smartphone must be working: At the entrance to the airport or train station, you’ll be asked to open your “Health Status Quary System” app in WeChat to scan the QR code. You can enter the building when your picture and the sentence “no abnormal conditions” appear.

If you already have them, it is also possible to save the Covid test and the vaccination in the app. Vaccinations are currently not mandatory. The phone and passport numbers are stored in the app so that the authorities can inform people if they have been in the vicinity of a person suffering from Covid. Frank Sieren/Felix Lee

In normal years, many foreigners leave China to escape the wave of travel within the People’s Republic. For them, Chinese New Year is less of a holiday and more of a good opportunity for a short vacation. In major cities, many restaurants and smaller shops are closed over the holidays as employees head home. Expats in China then like to use the time for a few days in the sun – for example, in Thailand, Vietnam or on the island of Boracay, the Mallorca of the Philippines. Others decide to go skiing, to the north of South Korea or to Japan, where there are large ski resorts with hot springs.

This year, however, that is not possible: Three weeks of quarantine on return are too big a hurdle. Most expats are therefore staying at home this year and, at most, making excursions into the surrounding area – such as hiking the Great Wall, to the icy waterfalls, and to Nanshan, a small ski resort in Beijing’s Miyun district.

Those who can’t stand being out of the sun will also find a destination within China: some fly to the tropical island of Hainan, about a three-and-a-half-hour flight from Beijing. Daytime temperatures there are currently 25 degrees and the water is 23 degrees – in Beijing, on the other hand, temperatures currently hover between plus five and minus five degrees. For Hainan, however, tourists need a Covid test for both the outward and return journey. However, several travelers have already described that they did not have to show a test, at least when entering the island.

There are stricter controls when traveling to larger ski resorts within China: The ski regions are about a three-hour drive north of Beijing around the city of Chongli. The Winter Olympics are to be held there in a year. Temperatures can sometimes drop below minus 30 degrees.

Some expats, especially study abroad students who do not have family in China, are also invited home by their Chinese friends – which is considered a sign of great friendship. For those who are not going away and not looking for a Chinese family connection, some Beijing and Shanghai clubs and pubs have prepared CNY parties that closely resemble Western celebrations on New Year’s Eve. Frank Sieren

It will stay quiet in the Chinese capital for the CNY: The last time, the rules for New Year’s fireworks were tightened in December 2017 – since then, it is no longer allowed to set off fireworks within the 5th ring. The official reason given at the time was mainly air pollution. But the danger of the firecrackers also played a role: In February 2009, for example, a new, fortunately still uninhabited high-rise building went up in flames after a fireworks display in Beijing’s Central Business District. After that, fireworks were only allowed to be set off in Beijing’s city center in certain designated places. Eight years later, a complete ban was enforced. This year, however, the central official fireworks displays were also canceled in many cities.

The fireworks in Hong Kong are considered the most spectacular in China. It is set off in Victoria Harbour, the strait between Hong Kong Island and the mainland of Kowloon. Hundreds of thousands usually gather to see it. Hundreds of ships with onlookers anchor in the strait. In 2021, however, the fireworks are canceled due to Covid.

Traditionally, it is customary to launch fireworks not only at midnight – but every evening for at least the first three days of the Chinese New Year. Superstition has it that the louder the fireworks, the better the business and the harvest. Therefore, private fireworks, unlike official fireworks, are not particularly colorful but particularly loud.

The first fireworks also had no great light effects. They were pieces of bamboo filled with gunpowder that were thrown into the fire and then exploded. This is where the name Baozhu comes from: “exploding bamboo”. This happened 200 years before Christ in the city of Liuyang. Even today, the city of 1.5 million people in the southeast Chinese province of Hunan is the capital of fireworks production.

China produces around 90 percent of the world’s fireworks. 60 percent of them are produced in Liuyang. It is mostly women who produce them – a very dangerous profession. According to estimates by the Chinese Workplace Safety Administration, only coal mine work is more dangerous. In the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD), people started to wrap the firecrackers in lucky red paper.

For the superstitious, it is important to leave the red paper lying around after the explosion – so as not to sweep away good luck. Until a few years ago, downtown Beijing was littered with red paper scraps when the clouds from the explosions had cleared. In villages in the countryside, this is still the case today. Traditionally, smaller fireworks are set off before the New Year’s Eve dinner to invite in the ancestors, and then the main fireworks are set off at midnight to drive away evil spirits. The last chance to set off fireworks is at the Lantern Festival, which takes place 14 days after the Chinese New Year. Frank Sieren

Not only do red envelopes change hands on New Year’s Day, but products with the celebrated sign of the zodiac are also a welcome gift. From luxury labels to sports outfits and tech companies, the ox can also be found on clothing, accessories and even headphones designed especially for the CNY. European brands such as Burberry and Louis Vuitton (LV) present so-called capsule collections for the Chinese New Year. LV is offering scarves with a logo and a cartoon ox or leather key rings, among other things. British label Burberry is offering jackets and bags with the usual check pattern and ox head – customers can also buy a peaked cap with small ox horns sticking out. Nike is selling a CNY shoe with an ox print and a red cord.

Danish toy manufacturer Lego is offering a kit for a bovine made of Lego bricks for the Year of the Ox. Barbie maker Mattel is releasing a version of the doll in traditional qipao for the CNY celebrations. Tech giant Apple is offering limited edition headphones emblazoned with an ox figurine on their storage box, as well as several mugs, T-shirts and chopsticks with zodiac imprints. Traditionally, the new year should also begin with a new outfit, which is why clothing – with or without an ox – is a welcome gift, preferably in the lucky color of red. Amelie Richter

In the week before the Chinese New Year, decorations in the form of red lanterns, banners or New Year silhouettes are hung on the door frame, spring cleaning is done – and above all, tons of food are bought. New Year’s Eve also includes the New Year’s Eve feast, when the whole family gathers around the table. In addition to the jiaozis, these dishes belong on the New Year’s table, which not only provide for physical well-being but, above all, symbolically bring long life, harmony, prosperity and luck:

Fish: A whole fish belongs on the table. The word fish 鱼 (yú) is the same as the word for surplus. But be careful not to “flip” the fish, or the surplus will be reversed. And there must be leftovers from the fish to demonstrate that everything is abundant.

Long (living) noodles: “Longevity noodles” (cháng shòu miàn, 长寿面) are very popular, also for birthdays. The longer the noodles, the longer you live. Therefore, they won’t be broken when they are cooked, for example, because the pot is too small.

Chicken: Similar to the whole fish, the whole chicken serves as a symbol of unity. The chicken (zhěng jī,整鸡) is served whole, that is, with head and feet.

Mandarins/oranges (júzi, 桔子): The yellow-orange color of these fruits is associated with good luck, and depending on the Chinese dialect, the names of the fruits sound like “luck”. Fruits with leaves are especially popular for Chinese New Year, as they symbolize longevity.

Niangao: Another must-try is niangao (年糕, also known as Chinese New Year cake), which sounds like 年高, which means “higher year” or – more grammatically accurate – an “increasingly successful year.” Variations vary from region to region; while niangao in the north likes to be steamed into a round cake, it is also served hearty with pork in the Shanghai region.

Tangyuan (汤圆) are balls of glutinous rice flour cooked and served in a lightly sweetened soup. They can be large and filled (with sesame, peanut or red bean paste) or small and unfilled. They are eaten on the first full moon after the Chinese New Year for the Lantern Festival.

Sweets: Oh yes, sweets are definitely a must, not only for the kids to stay up late and scare away the New Year’s monster, but especially to sweeten life in the New Year as well. Ning Wang

To welcome the Year of the Ox, millions of dumplings are consumed at dining tables in China today. In northern China, in particular, jiaozi is simply part of the New Year. Since their shape resembles small gold bars used as currency in imperial times, they promise good luck and prosperity. Especially when you find the one coin hidden in a dumpling during the traditional New Year feast. Apart from small change, the dumplings are filled with anything that tastes good: pork, shrimp, Chinese leek, beef or mutton, fried egg, carrots, eggplant, fennel greens and shepherd’s purse are also popular. Even jiaozi with cheese or chocolate filling can be found. When the whole family gets involved, the jiaozi production is at least as much fun as the food itself. Why don’t you give it a try? Chef Yuhang Wu provides the recipe.

Ingredients (serves 4):

Dough:

500g flour

250ml water

3g salt

Filling:

15g ginger

15g leek

2g Sichuan pepper

150ml boiling water

300g organic pork mince

500g Chinese cabbage, finely chopped

3 tbsp light soy sauce

1 tbsp dark soy sauce

1 tbsp oyster sauce

3 tsp salt

1 tsp sugar

4 tbsp sesame oil

Preparation:

The secret of this jiaozi recipe is the spice infusion of ginger, leek and Sichuan pepper. It gives the filling its flavor. Simply pour boiling water over the coarsely chopped ingredients and leave to infuse for 20 minutes.

Then wash the Chinese cabbage thoroughly, cut it into very fine cubes, add 1 tsp salt, mix thoroughly and set aside so that the salt can remove the water from the cabbage.

Dough:

In a large bowl, mix flour with salt. Gradually add water, using two chopsticks to mix with the flour. When all the flour is combined, keep pressing down and folding the dough with a clenched fist until it forms a mass. Knead this mass until it is smooth and malleable. Then cover with cling film and set aside.

Filling:

Wring out the finely minced Chinese cabbage with your hands; the drier the better. While stirring, pour the cooled spice infusion through a sieve and gradually add the liquid to the minced pork. Stirring works best with two chopsticks held in one hand. Keep stirring in one direction until the meat completely absorbs the spice infusion. This may take up to five minutes. Then add light and dark soy sauce, oyster sauce, salt and sugar and continue stirring until these ingredients have also combined completely with the meat mixture. Only now the sesame oil is added and stirred thoroughly with the meat mixture. Finally, add the finely minced Chinese cabbage, as dry as possible. Stir one last time until you have an even filling that is firm enough to stick a chopstick in.

Roll out…

Now the grand finale begins. Cut the dough into four equal, elongated pieces and form each of them into an approx. 2cm thick dough roll by hand. From this roll, cut 20 equal pieces of about 10g each with the knife or dough scraper and turn them in flour so they will not stick. Flatten each piece by hand with the cut side on top. Roll out the slices to about the size of the palm of your hand. In China, a small rolling pin is used for this purpose, but a large rolling pin or a clean glass bottle can also be used. Professionals manage to make the dough slices a little thinner at the edges than in the middle. Cover the rolled-out dough patties with cling film until you are ready to fill them.

…fill…

Place one dough patty at a time on the palm of your hand, spread about a tablespoon of the filling in the middle, and then fold the upper edge upwards to form a small half-moon. Closing the jiaozi requires a little practice but is not that difficult if you follow a few rules: Do not use too much filling and only spread it in the middle; after the folding, first press the two halves together only in the middle of the edge and only then both sides. Place the finished jiaozi on a well-floured surface so that they do not stick.

…and cook

Bring unsalted water to a boil in a large pot and carefully add the jiaozi. Then stir gently with a ladle so that no jiaozi stick to the bottom of the pot. After a few minutes, the jiaozi will float to the surface. Now add another 50ml of cold water, wait until the water boils and add another 50ml or so of cold water. When the water boils bubbly for the third time, the jiaozi are ready and can be ladled onto the plate. Jiaozi taste best when dipped in a dip of soy sauce, black vinegar and a little chili oil. Yuhang Wu / Jonas Borchers

Bon appetit and good luck and wealth in the new Year of the Ox!

Yuhang Wu and Jonas Borchers opened their restaurant UUU in Berlin-Wedding in September 2020. Previously, Wu worked in the country’s best Michelin-starred kitchens. Together with their guests, they want to rediscover Chinese cuisine at UUU. You can order the jiaozi at the online shop of their restaurant UUU: uuu-berlin.de/athome/