Tomorrow is Christmas. A holiday that also plays an important role in China. And not just as a consumer holiday. Officially, around 44 million Christians live in China. According to estimates, their number could actually be as high as 100 million, if the members of the so-called “underground” or “house churches” are included. These operate in a gray area. They are tolerated, but under Xi Jinping their freedoms have since been curtailed. And the pandemic has also made the work of the churches even harder. Fabian Peltsch reports on how China’s Christians celebrate Christmas.

China’s increasingly ideology-driven policies are a nightmare for wealthy Chinese. They have long benefited from the country’s economic reforms, but they fear for their wealth, especially after the Party Congress in October. The only question is – where to put their money? Hong Kong is no longer an alternative, because Beijing’s influence is now also too great there. Singapore is much more tempting. Joern Petring reports on how the upper class is making its way to the city-state.

Every year, the word of the year is chosen. In Germany, it is hardly worth more than a short news story. Perhaps even a smirk, when the youth word of the year is read out on the news with a straight face. China also chooses the word of the year. But while suggestions from the population were once welcome, the word of the year has long since become a political matter under Xi Jinping. China picks different words for in- and outside the country, and of course one of the two sides comes off particularly well. Johnny Erling explains how China looks for its words of the year.

Next week, we will be sitting under the Christmas tree instead of the China.Table. Our editors are taking a short Christmas break. What has been going on in China has kept us on our toes, especially in the second half of the year. We hope that you have enjoyed our reports. While we all recharge our batteries for the new year, we will of course be keeping a close eye on the news situation in China. Naturally, we will keep you up to date on any extraordinary developments in the form of a special edition.

We wish you relaxing days, a peaceful Christmas and a happy New Year!

In recent years, Chinese nationalists repeatedly called for Christmas boycotts. At Nanjing University in 2018, for example, students were urged to stop celebrating “foreign festivals.” “We celebrate only Chinese holidays,” was the message from the administration. The governments of several cities in Hebei, Guizhou and Guangxi provinces also banned Christmas decorations from public spaces in the past. But this was more the result of patriotic zeal.

Christmas is not officially forbidden in China. Christmas decorations can still be found on every corner and Santa Clauses dangle from the ceiling in shopping malls. Decorated plastic trees advertise the latest Christmas discounts. Hardly anyone associates the holiday with the birth of Jesus in this consumerist atmosphere. Young Chinese celebrate Christmas more as a kind of Valentine’s Day, posting romantic winter pictures, for example, of ice skating or slurping cinnamon-rich winter editions at Starbucks. And they are, after all, at the source: China is still the world’s largest producer of Christmas decorations.

But many Christians in China also consider Christmas the most important holiday of the year – even more important than the Spring Festival. Masses could once again be held in the official state churches this year, depending on the pandemic situation – China has a state church that has broken away from the pope and recognizes the Communist Party as the highest authority. There is also an underground church, loyal to the Vatican, which holds its congregations mostly in private rooms. Officially, about 44 million Christians live in China. According to the American human rights organization Freedom House, the number is probably closer to 100 million, if members of the so-called “underground” or “house churches” are included.

The house churches operate in a gray area and are sometimes more and sometimes less tolerated, depending on the political climate. Under Xi Jinping, their freedoms have been drastically curtailed, says Thomas Mueller of Open Doors, an international aid organization that helps Christians in more than 70 countries around the world. “Xi cares mostly about control, and religious freedom is one of the key issues that pains him.” The Christmas story is considered inherently subversive in this regard, Mueller explains. “A savior who comes into the world as a human being is not something the Communist Party can accept.”

In the past, house church members would have rented hotels or entire floors in office buildings during Christmas Eve and other Christian holidays to hold Christmas celebrations. During the pandemic, however, such events, which sometimes drew 1,000 people together, were banned – bans that have not yet been lifted, although other gatherings have been permitted again as the Covid measures have been lifted, Mueller explains. “There may be some isolated exceptions, but essentially their gatherings are no longer possible right now.”

Because the house churches were never officially allowed to exist in the first place, they are unable to veto government agencies. “When these Christians come together on Christmas Eve, it now often no longer looks like a church service, but more like they are simply having dinner together. The more individual congregations fragment into micro-groups, the fewer pastors are available,” Mueller said. Online sermons had become an alternative during the pandemic.

However, the online regulations for religious communities introduced in March 2022 require that anyone who wants to share religious content on the Internet needs a license (China.Table reported). “The house churches, however, are not eligible for these licenses,” Mueller said. As a result, many Christians would have already come to terms with the fact that Christmas can no longer be celebrated as a community as it used to be. At the moment, this applies to members of the state church as well, a Catholic woman from Beijing told China.Table. “At the moment, churches are not open to the public because of the pandemic. Many people have fallen ill, so I will spend Christmas alone at home this year.” Before the pandemic, she used to sing in church with other believers every year and give small gifts to volunteers. “The atmosphere will be very different this year.”

Kia Meng Loh is a busy man these days. He heads the Private Wealth and Family Offices department at the renowned law firm Dentons Rodyk in Singapore. Wealthy foreigners who want to move to Singapore have found the right partner. Loh’s services are currently in particular demand among Chinese.

“The number of wealthy Chinese moving to Singapore has increased recently,” says Loh in an interview with China.Table. Potential clients from China now account for about half of all the inquiries he and his team handle. According to figures from the Monetary Authority of Singapore, just 33 family offices were established by Chinese in the city in 2019. Last year, the number was already 175, and another record is expected this year.

Other consultants in the city confirm the trend. And they often cite similar reasons why their Chinese clients are seeking refuge, or at least a second foothold, in Singapore. Especially wealthy Chinese, who were able to profit from the fruits of economic reforms in the past decades, are now drawn to the city-state.

They said they no longer recognized their own country. Not only the strict Covid policy, but above all the increasingly ideology-driven policies of the Chinese leadership are greatly concerning, it is said in Singapore. The worries of the Chinese upper class have intensified since the Party Congress in October.

At the Congress, state and party leader Xi Jinping not only presented a new leadership there that no longer includes a single economic reformer. He also reiterated his mantra of “common prosperity”. Although this slogan already existed during the founding days of the Communist Party, it only has been fervently propagated after Xi came to power. The leadership in Beijing has had enough of “irrational capital expansion” and “barbaric growth,” Xi said in a speech last year at the height of his crackdown on the country’s tech executives.

Most Chinese who currently try to bring themselves or their wealth do not seek a safe haven in Europe or the USA right away. Many prefer to stay in Asia. Hong Kong is no longer an option because Beijing has also begun to spread its influence there. So Singapore is high on the list.

In Singapore, Loh says, the Chinese particularly appreciate the political climate and stability. Another important factor are the pro-business laws, which make it easy for wealthy foreigners to set up their own asset management company and thus obtain a residence permit. Taxes are also low. Like Hong Kong, Singapore is an important financial hub. Many rich Chinese who previously stored parts of their assets in the special administrative region are now shifting their assets to Singapore.

According to advisors in the city, considerably more Chinese would probably try to move money to Singapore. But Beijing is making things increasingly difficult for its wealthy upper class. The already strict capital export controls have not only been tightened further, but are also being monitored more closely. And it is not only money that can hardly cross the border. Covid currently makes it almost impossible for Chinese to go on tourist trips outside the country.

“I heard of cases where Chinese people have enrolled in a master’s program in Singapore as a way to get permission to leave the country,” Loh says. Once they are in the city, they set up a family office.

Loh observes another interesting trend. Apparently, it is not only wealthy Chinese from the People’s Republic who look to the future with great concern. Recently, there have been more and more inquiries from Taiwan as well. Joern Petring

China apparently plans to relax quarantine rules for foreign travelers in January. This was reported by Bloomberg News on Thursday, citing people familiar with the matter.

Authorities reportedly consider a “0+3″ solution“, which would eliminate the requirement to stay in a quarantine hotel or isolation facility. Instead, arrivals would be monitored for three days after arrival. What type of monitoring would be used and whether it would include quarantine at home is unclear at this point. The details of the plan would still be worked out, including when the measures would begin in January.

Currently, travelers are still required to spend the first five days after arrival in China in quarantine in a hotel or other facility. rtr/fpe

China’s sudden abolition of zero-Covid continues to drive increased demand for fever medicines and virus test kits (China.Table reported). Ibuprofen and paracetamol in particular are currently in short supply in China. Pharmacies are strictly rationing these medications to prevent hoarding in case of emergency. Pharmacies in Singapore also report shortages. Local Chinese would buy up stocks for their relatives and friends in China, the South China Morning Post reported on Thursday. The Shun Xing Express courier service already announced to only allow 50 people per day to send medications back to China. Similar hoarding has also been observed in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and even Australia, CNN reports.

Experts fear that the situation in China will also lead to supply problems for painkillers and antipyretics in Germany. Only six manufacturers worldwide now produce generic ibuprofen, four of them located in Asia: Hubei Biocause and Shandong Xinhua in China, Solara and IOLPC in India, and BASF in Germany (via a factory in Texas) and SI Group in the USA.

Meanwhile, India announced plans to export antipyretic drugs to China. The country is one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical manufacturers aside from China. “We are keeping an eye on the Covid situation in China,” Foreign Ministry spokesman Arindam Bagchi said at a press conference. “We have always helped other countries as the pharmacy of the world.” The Chinese Embassy in Delhi did not comment on the offer so far. fpe

According to Taiwan’s Ministry of Defense, China’s military entered the island’s air defense zone with 39 aircraft. The government in Taipei responded by dispatching numerous jets in return to warn the Chinese planes.

The ministry released a map showing that the Chinese military aircraft flew over a waterway known as the Bashi Channel to an area off the southeastern coast of the island, among other places. Three Chinese naval vessels were also spotted near Taiwan.

China has been increasing pressure on Taiwan for years. Especially around the visit of former US Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi in August, China had conducted numerous military exercises around the island. rtr/jul

The Philippines’ Department of National Defense ordered the military to increase its presence in the South China Sea. It reportedly observed Chinese activity in waters near the Philippines-administered and strategically important Pag-asa Island, also known as Thitu Island. The island is part of the disputed Spratly Islands. China’s activities in the area were not specified. A week ago, however, China’s construction activities on four uninhabited islands in the Spratly archipelago surfaced.

The ministry noted that an incursion into the Philippines’ 200-mile-wide exclusive economic zone, which includes Pag-asa Island, would represent a threat. It warned China to respect the rules-based international order and not to exacerbate tensions. The Chinese Embassy in Manila stressed that China adheres to the common consensus not to develop uninhabited reefs and islands.

China lays claim to much of the South China Sea. However, this also includes numerous islands and land masses claimed by Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam. jul/rtr

Every December 20, Beijing linguists from publishing houses, media, and universities invite the public to submit their picks for the ten most popular Chinese words and slogans of the year. They have done this every year since 2006. Initially, their list was simply intended to show how the Chinese see and evaluate the situation at home and abroad. It also served to measure the mood of the people and as an alarm signal for Beijing’s leadership.

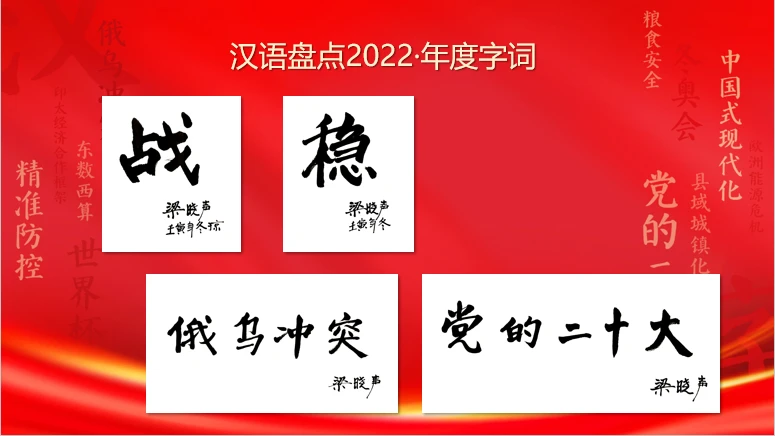

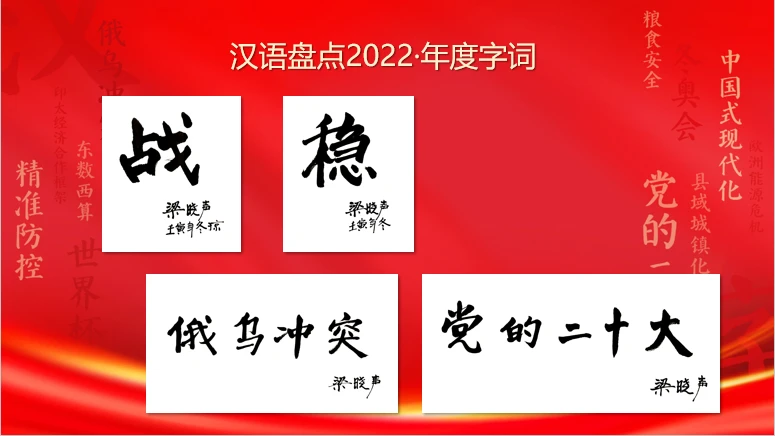

Since Xi Jinping took office in 2013, the party decides what the people should think and already decides and censors the words in the selection lists. No wonder the party also likes the result in 2022. “Stability” and the triumphant “20th Party Congress” won the words of the year for China. War, conflict and chaos, on the other hand, characterize foreign countries. There is no place for “Zeitenwende” in Beijing’s choice of words.

As expected, the German Language Society chose Olaf Scholz’s phrase “Zeitenwende” as its word of the year 2022. In early December, the Chancellor also popularized his linguistic creation internationally in another op-ed. He defined Zeitenwende as “an epochal tectonic shift” after both the Russian war of aggression on Ukraine and pandemic, climate change, inflation and political chaos shook the world all at once.

Consequently, the lexicographers of the Collins English Dictionary chose the word “permacrisis” as the British word of the year. The term, which first appeared in the 1970s, describes “an extended period of instability and insecurity.” Tokyo’s Kanji Aptitude Testing Foundation went one step further. It picked the kanji 戦 (pronounced sen in Japanese), a character once adopted from Chinese. It means war. Twenty years ago, Tokyo already named “sen” the word of the year. The trigger, like the Ukraine attack today, was the al-Qaeda terrorist attack on the United States on September 11, 2001, and its impact on the entire world. Even Beijing was shocked at the time.

Today, that is different in China. Although, like Japan, it also chose the character for war 战 (戦) as the word of the year 2022, but only within its category for international words (国际字). They represent the People’s Republic view of foreign countries, but otherwise have nothing to do with China. The word of the year chosen for China (国内字) is wen (稳), “stability.” Beijing also differentiates between inside and outside when choosing the ten most popular slogans or catchphrases for 2022. First among its new ten national slogans (国内词) is the slogan of the victorious “20th Communist Party Congress” (党的二十大). On the list of international buzzwords (国际词), the phrase “Russian-Ukrainian conflict” (俄乌冲突) moved up.

The absurdity of the lists and their picks can be seen in Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. In China, it is not allowed to be called a war. Beijing refers to it as a “conflict,” even though Russia has been bombing Ukraine for ten months, both sides have suffered tens of thousands of casualties, and millions of Ukrainians have become refugees. Xi Jinping stands by his comrade-in-arms Putin, even down to the wording.

Initially, China’s search for the words of the year was still conducted professionally. The lists with a selection of 10 words and terms each, which are posted online for voting, are actually compiled by experts from the national center for language research (国家语言资源监测与研究中心), from book and online publishers, universities and Internet platforms. They draw on their year-round analysis of millions of data from print, TV and online media, from which they filter out words and terms according to their frequency and meaning.

But nowadays, the party is in charge. This year’s month-long pre-selection process for China’s words of the year turned into a farce. Terms such as “zero-Covid” (动态清零) or lockdown policy did not appear on the nomination lists, even though they kept China in their grip all year long. In fact, since Beijing completely changed its pandemic response on December 7, these words have become taboo. Thus, the only obfuscating paraphrase found in the ten buzzwords selected for 2022 is “precise prevention and control” (精准防控). The words pandemic or Cmicron variant can only appear in the list of international words or slogans of the year.

The People’s Daily triumphantly applauded the results of China’s word of the year, announced at a big event in Beijing on December 20, under the headline, “stability comes first!” (稳 “字当头!). It acted as if it was a huge surprise. China’s English China Daily newspaper celebrated the vote under a different headline in its Wednesday edition: “’20th CPC Congress’ voted top phrase of year.” The paper also praised other propaganda phrases, from “China’s modernization” (中国式现代化) to “whole-process people’s democracy” (全过程人民民主), which China’s dictatorship uses to praise itself in party gibberish.

The officially orchestrated search for the word of the year provoked critical bloggers to weigh in. They pleaded for a word that was popular on the net but constantly deleted. It is called bai (白, white). In combinations such as “white revolution” or “white paper,” it has come to symbolize public protests against Beijing’s zero-Covid policies. The character yang (阳) also often appeared on the web. It means positive, that is, to be infected with Covid. Bloggers equated the sign with the identically pronounced sign yang (羊), to be a “sheep”. Don’t be sheep, they yell out to their readers. For two days, more than 100,000 users rejoiced over the online word cao (操, actually: to handle, to drive). Then even the censors realized that it was slang for the extended middle finger, with the subversive message to the party: “Screw you”.

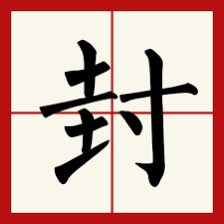

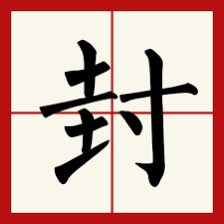

Another blogger proposed two words for 2022 and 2023. For the past year, 封 (feng) “being trapped in lockdown” is a fitting expression, and for the coming year 疯 (feng) follows: “In 2023, we go completely nuts” (我一下选两,明年就省啦! 22年是 “封”,23年是 “疯).

But despite all the Internet mockery, the party never before exerted as much influence as it did this year on the selection of a word of the year. This was different at the beginning of Xi Jinping’s reign in 2013. Even then, the language commission had put Xi’s key political words at the top of its list of suggestions. Most notably, the characters meng (梦) for Xi’s dream of making China’s nation rich and strong, and lian (廉) for his purge campaign against corrupt officials, were considered words of the year for 2013. But 100,000 online voters voted differently. 42 percent chose the character fang (房) for house and 25 percent chose mai (霾) for smog. Their alternative words reflected the frustration that their dream of owning their own apartment was unaffordable and unattainable. Mai was used to protest against air pollution.

In 2013, publishing director Liu Zuochen of the Commercial Press, who led the word of the year project, told me: “We want our search for words and terms of the year to also give our government an important clue: What do the people want? What do they think? How did it feel this year?”

In 2009, the word bei (被) chosen by a majority as the word of the year had already given Beijing’s politicians food for thought. Bei is used as a passive character and stood for the citizens’ anger at feeling increasingly disempowered and controlled by an all-powerful party bureaucracy. They fought back linguistically: When Beijing’s official figures glossed over the extent of inflation, they responded with the passive form: “We have been price-stabilized.” When propaganda declared them happy Chinese, they said, “We were made happy.” At the time, even the official news agency Xinhua regarded the choice of bei as the word of the year as a latent signal for their “call for more freedom” and self-determination. South China’s Nanfang Dushibao newspaper commented that in a situation where open criticism and opposition are not tolerated, citizens use a word to “show awareness of wanting to exercise their civil rights.”

Today, Xi Jinping’s party would not only prevent such comments. It does not even let online voters pick China’s word of the year. Courageous citizens protest in a cat-and-mouse game with censors. Following the announcement of the official words of the year, bloggers posted on Wednesday under the headline “Which word would you choose?” 53 individual characters to choose from online. In combination with other words, they become critical terms that challenge Xi’s party rule. The list starts with the character for “white”, China’s new protest color.

Han Shangyou has been appointed CEO of Douyin. The 32-year-old is thus the youngest executive at the helm of the popular app. Douyin, like TikTok, the Western version of the short video app, is owned by Chinese tech giant ByteDance. Han joined the Beijing-based company in 2016. Previously, he was responsible for local services and the open developer platform at Douyin.

Lu Weibing will become president of device and smartphone manufacturer Xiaomi. He will succeed Wang Xiang effective December 30, the company’s chairman and founder Lei Jun announced Thursday. Two co-founders, Hong Feng and Wang Chuan, will also retire from the company’s day-to-day operations, Lei said in his statement. Lu, 46, most recently held the positions of president of the China region and head of the international division.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Backlit by the setting sun, a flock of cranes passes over Poyang Lake in Nanchang, eastern Jiangxi Province. The largest freshwater lake in China is an important wintering site for migratory birds. This year, it has been partially dried up by droughts. Chinese wildlife conservationists have therefore joined forces to help the animals with water and food. In China, the crane is traditionally considered a symbol of wisdom and long life.

Tomorrow is Christmas. A holiday that also plays an important role in China. And not just as a consumer holiday. Officially, around 44 million Christians live in China. According to estimates, their number could actually be as high as 100 million, if the members of the so-called “underground” or “house churches” are included. These operate in a gray area. They are tolerated, but under Xi Jinping their freedoms have since been curtailed. And the pandemic has also made the work of the churches even harder. Fabian Peltsch reports on how China’s Christians celebrate Christmas.

China’s increasingly ideology-driven policies are a nightmare for wealthy Chinese. They have long benefited from the country’s economic reforms, but they fear for their wealth, especially after the Party Congress in October. The only question is – where to put their money? Hong Kong is no longer an alternative, because Beijing’s influence is now also too great there. Singapore is much more tempting. Joern Petring reports on how the upper class is making its way to the city-state.

Every year, the word of the year is chosen. In Germany, it is hardly worth more than a short news story. Perhaps even a smirk, when the youth word of the year is read out on the news with a straight face. China also chooses the word of the year. But while suggestions from the population were once welcome, the word of the year has long since become a political matter under Xi Jinping. China picks different words for in- and outside the country, and of course one of the two sides comes off particularly well. Johnny Erling explains how China looks for its words of the year.

Next week, we will be sitting under the Christmas tree instead of the China.Table. Our editors are taking a short Christmas break. What has been going on in China has kept us on our toes, especially in the second half of the year. We hope that you have enjoyed our reports. While we all recharge our batteries for the new year, we will of course be keeping a close eye on the news situation in China. Naturally, we will keep you up to date on any extraordinary developments in the form of a special edition.

We wish you relaxing days, a peaceful Christmas and a happy New Year!

In recent years, Chinese nationalists repeatedly called for Christmas boycotts. At Nanjing University in 2018, for example, students were urged to stop celebrating “foreign festivals.” “We celebrate only Chinese holidays,” was the message from the administration. The governments of several cities in Hebei, Guizhou and Guangxi provinces also banned Christmas decorations from public spaces in the past. But this was more the result of patriotic zeal.

Christmas is not officially forbidden in China. Christmas decorations can still be found on every corner and Santa Clauses dangle from the ceiling in shopping malls. Decorated plastic trees advertise the latest Christmas discounts. Hardly anyone associates the holiday with the birth of Jesus in this consumerist atmosphere. Young Chinese celebrate Christmas more as a kind of Valentine’s Day, posting romantic winter pictures, for example, of ice skating or slurping cinnamon-rich winter editions at Starbucks. And they are, after all, at the source: China is still the world’s largest producer of Christmas decorations.

But many Christians in China also consider Christmas the most important holiday of the year – even more important than the Spring Festival. Masses could once again be held in the official state churches this year, depending on the pandemic situation – China has a state church that has broken away from the pope and recognizes the Communist Party as the highest authority. There is also an underground church, loyal to the Vatican, which holds its congregations mostly in private rooms. Officially, about 44 million Christians live in China. According to the American human rights organization Freedom House, the number is probably closer to 100 million, if members of the so-called “underground” or “house churches” are included.

The house churches operate in a gray area and are sometimes more and sometimes less tolerated, depending on the political climate. Under Xi Jinping, their freedoms have been drastically curtailed, says Thomas Mueller of Open Doors, an international aid organization that helps Christians in more than 70 countries around the world. “Xi cares mostly about control, and religious freedom is one of the key issues that pains him.” The Christmas story is considered inherently subversive in this regard, Mueller explains. “A savior who comes into the world as a human being is not something the Communist Party can accept.”

In the past, house church members would have rented hotels or entire floors in office buildings during Christmas Eve and other Christian holidays to hold Christmas celebrations. During the pandemic, however, such events, which sometimes drew 1,000 people together, were banned – bans that have not yet been lifted, although other gatherings have been permitted again as the Covid measures have been lifted, Mueller explains. “There may be some isolated exceptions, but essentially their gatherings are no longer possible right now.”

Because the house churches were never officially allowed to exist in the first place, they are unable to veto government agencies. “When these Christians come together on Christmas Eve, it now often no longer looks like a church service, but more like they are simply having dinner together. The more individual congregations fragment into micro-groups, the fewer pastors are available,” Mueller said. Online sermons had become an alternative during the pandemic.

However, the online regulations for religious communities introduced in March 2022 require that anyone who wants to share religious content on the Internet needs a license (China.Table reported). “The house churches, however, are not eligible for these licenses,” Mueller said. As a result, many Christians would have already come to terms with the fact that Christmas can no longer be celebrated as a community as it used to be. At the moment, this applies to members of the state church as well, a Catholic woman from Beijing told China.Table. “At the moment, churches are not open to the public because of the pandemic. Many people have fallen ill, so I will spend Christmas alone at home this year.” Before the pandemic, she used to sing in church with other believers every year and give small gifts to volunteers. “The atmosphere will be very different this year.”

Kia Meng Loh is a busy man these days. He heads the Private Wealth and Family Offices department at the renowned law firm Dentons Rodyk in Singapore. Wealthy foreigners who want to move to Singapore have found the right partner. Loh’s services are currently in particular demand among Chinese.

“The number of wealthy Chinese moving to Singapore has increased recently,” says Loh in an interview with China.Table. Potential clients from China now account for about half of all the inquiries he and his team handle. According to figures from the Monetary Authority of Singapore, just 33 family offices were established by Chinese in the city in 2019. Last year, the number was already 175, and another record is expected this year.

Other consultants in the city confirm the trend. And they often cite similar reasons why their Chinese clients are seeking refuge, or at least a second foothold, in Singapore. Especially wealthy Chinese, who were able to profit from the fruits of economic reforms in the past decades, are now drawn to the city-state.

They said they no longer recognized their own country. Not only the strict Covid policy, but above all the increasingly ideology-driven policies of the Chinese leadership are greatly concerning, it is said in Singapore. The worries of the Chinese upper class have intensified since the Party Congress in October.

At the Congress, state and party leader Xi Jinping not only presented a new leadership there that no longer includes a single economic reformer. He also reiterated his mantra of “common prosperity”. Although this slogan already existed during the founding days of the Communist Party, it only has been fervently propagated after Xi came to power. The leadership in Beijing has had enough of “irrational capital expansion” and “barbaric growth,” Xi said in a speech last year at the height of his crackdown on the country’s tech executives.

Most Chinese who currently try to bring themselves or their wealth do not seek a safe haven in Europe or the USA right away. Many prefer to stay in Asia. Hong Kong is no longer an option because Beijing has also begun to spread its influence there. So Singapore is high on the list.

In Singapore, Loh says, the Chinese particularly appreciate the political climate and stability. Another important factor are the pro-business laws, which make it easy for wealthy foreigners to set up their own asset management company and thus obtain a residence permit. Taxes are also low. Like Hong Kong, Singapore is an important financial hub. Many rich Chinese who previously stored parts of their assets in the special administrative region are now shifting their assets to Singapore.

According to advisors in the city, considerably more Chinese would probably try to move money to Singapore. But Beijing is making things increasingly difficult for its wealthy upper class. The already strict capital export controls have not only been tightened further, but are also being monitored more closely. And it is not only money that can hardly cross the border. Covid currently makes it almost impossible for Chinese to go on tourist trips outside the country.

“I heard of cases where Chinese people have enrolled in a master’s program in Singapore as a way to get permission to leave the country,” Loh says. Once they are in the city, they set up a family office.

Loh observes another interesting trend. Apparently, it is not only wealthy Chinese from the People’s Republic who look to the future with great concern. Recently, there have been more and more inquiries from Taiwan as well. Joern Petring

China apparently plans to relax quarantine rules for foreign travelers in January. This was reported by Bloomberg News on Thursday, citing people familiar with the matter.

Authorities reportedly consider a “0+3″ solution“, which would eliminate the requirement to stay in a quarantine hotel or isolation facility. Instead, arrivals would be monitored for three days after arrival. What type of monitoring would be used and whether it would include quarantine at home is unclear at this point. The details of the plan would still be worked out, including when the measures would begin in January.

Currently, travelers are still required to spend the first five days after arrival in China in quarantine in a hotel or other facility. rtr/fpe

China’s sudden abolition of zero-Covid continues to drive increased demand for fever medicines and virus test kits (China.Table reported). Ibuprofen and paracetamol in particular are currently in short supply in China. Pharmacies are strictly rationing these medications to prevent hoarding in case of emergency. Pharmacies in Singapore also report shortages. Local Chinese would buy up stocks for their relatives and friends in China, the South China Morning Post reported on Thursday. The Shun Xing Express courier service already announced to only allow 50 people per day to send medications back to China. Similar hoarding has also been observed in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and even Australia, CNN reports.

Experts fear that the situation in China will also lead to supply problems for painkillers and antipyretics in Germany. Only six manufacturers worldwide now produce generic ibuprofen, four of them located in Asia: Hubei Biocause and Shandong Xinhua in China, Solara and IOLPC in India, and BASF in Germany (via a factory in Texas) and SI Group in the USA.

Meanwhile, India announced plans to export antipyretic drugs to China. The country is one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical manufacturers aside from China. “We are keeping an eye on the Covid situation in China,” Foreign Ministry spokesman Arindam Bagchi said at a press conference. “We have always helped other countries as the pharmacy of the world.” The Chinese Embassy in Delhi did not comment on the offer so far. fpe

According to Taiwan’s Ministry of Defense, China’s military entered the island’s air defense zone with 39 aircraft. The government in Taipei responded by dispatching numerous jets in return to warn the Chinese planes.

The ministry released a map showing that the Chinese military aircraft flew over a waterway known as the Bashi Channel to an area off the southeastern coast of the island, among other places. Three Chinese naval vessels were also spotted near Taiwan.

China has been increasing pressure on Taiwan for years. Especially around the visit of former US Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi in August, China had conducted numerous military exercises around the island. rtr/jul

The Philippines’ Department of National Defense ordered the military to increase its presence in the South China Sea. It reportedly observed Chinese activity in waters near the Philippines-administered and strategically important Pag-asa Island, also known as Thitu Island. The island is part of the disputed Spratly Islands. China’s activities in the area were not specified. A week ago, however, China’s construction activities on four uninhabited islands in the Spratly archipelago surfaced.

The ministry noted that an incursion into the Philippines’ 200-mile-wide exclusive economic zone, which includes Pag-asa Island, would represent a threat. It warned China to respect the rules-based international order and not to exacerbate tensions. The Chinese Embassy in Manila stressed that China adheres to the common consensus not to develop uninhabited reefs and islands.

China lays claim to much of the South China Sea. However, this also includes numerous islands and land masses claimed by Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam. jul/rtr

Every December 20, Beijing linguists from publishing houses, media, and universities invite the public to submit their picks for the ten most popular Chinese words and slogans of the year. They have done this every year since 2006. Initially, their list was simply intended to show how the Chinese see and evaluate the situation at home and abroad. It also served to measure the mood of the people and as an alarm signal for Beijing’s leadership.

Since Xi Jinping took office in 2013, the party decides what the people should think and already decides and censors the words in the selection lists. No wonder the party also likes the result in 2022. “Stability” and the triumphant “20th Party Congress” won the words of the year for China. War, conflict and chaos, on the other hand, characterize foreign countries. There is no place for “Zeitenwende” in Beijing’s choice of words.

As expected, the German Language Society chose Olaf Scholz’s phrase “Zeitenwende” as its word of the year 2022. In early December, the Chancellor also popularized his linguistic creation internationally in another op-ed. He defined Zeitenwende as “an epochal tectonic shift” after both the Russian war of aggression on Ukraine and pandemic, climate change, inflation and political chaos shook the world all at once.

Consequently, the lexicographers of the Collins English Dictionary chose the word “permacrisis” as the British word of the year. The term, which first appeared in the 1970s, describes “an extended period of instability and insecurity.” Tokyo’s Kanji Aptitude Testing Foundation went one step further. It picked the kanji 戦 (pronounced sen in Japanese), a character once adopted from Chinese. It means war. Twenty years ago, Tokyo already named “sen” the word of the year. The trigger, like the Ukraine attack today, was the al-Qaeda terrorist attack on the United States on September 11, 2001, and its impact on the entire world. Even Beijing was shocked at the time.

Today, that is different in China. Although, like Japan, it also chose the character for war 战 (戦) as the word of the year 2022, but only within its category for international words (国际字). They represent the People’s Republic view of foreign countries, but otherwise have nothing to do with China. The word of the year chosen for China (国内字) is wen (稳), “stability.” Beijing also differentiates between inside and outside when choosing the ten most popular slogans or catchphrases for 2022. First among its new ten national slogans (国内词) is the slogan of the victorious “20th Communist Party Congress” (党的二十大). On the list of international buzzwords (国际词), the phrase “Russian-Ukrainian conflict” (俄乌冲突) moved up.

The absurdity of the lists and their picks can be seen in Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. In China, it is not allowed to be called a war. Beijing refers to it as a “conflict,” even though Russia has been bombing Ukraine for ten months, both sides have suffered tens of thousands of casualties, and millions of Ukrainians have become refugees. Xi Jinping stands by his comrade-in-arms Putin, even down to the wording.

Initially, China’s search for the words of the year was still conducted professionally. The lists with a selection of 10 words and terms each, which are posted online for voting, are actually compiled by experts from the national center for language research (国家语言资源监测与研究中心), from book and online publishers, universities and Internet platforms. They draw on their year-round analysis of millions of data from print, TV and online media, from which they filter out words and terms according to their frequency and meaning.

But nowadays, the party is in charge. This year’s month-long pre-selection process for China’s words of the year turned into a farce. Terms such as “zero-Covid” (动态清零) or lockdown policy did not appear on the nomination lists, even though they kept China in their grip all year long. In fact, since Beijing completely changed its pandemic response on December 7, these words have become taboo. Thus, the only obfuscating paraphrase found in the ten buzzwords selected for 2022 is “precise prevention and control” (精准防控). The words pandemic or Cmicron variant can only appear in the list of international words or slogans of the year.

The People’s Daily triumphantly applauded the results of China’s word of the year, announced at a big event in Beijing on December 20, under the headline, “stability comes first!” (稳 “字当头!). It acted as if it was a huge surprise. China’s English China Daily newspaper celebrated the vote under a different headline in its Wednesday edition: “’20th CPC Congress’ voted top phrase of year.” The paper also praised other propaganda phrases, from “China’s modernization” (中国式现代化) to “whole-process people’s democracy” (全过程人民民主), which China’s dictatorship uses to praise itself in party gibberish.

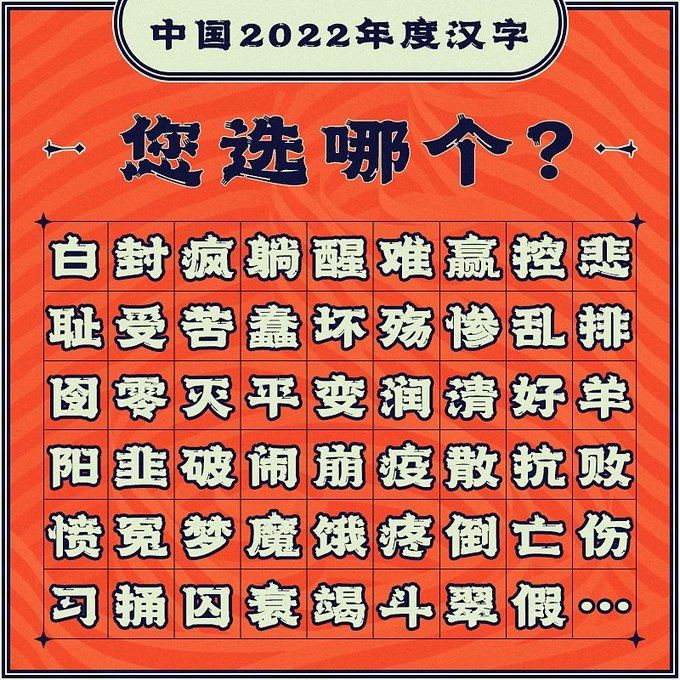

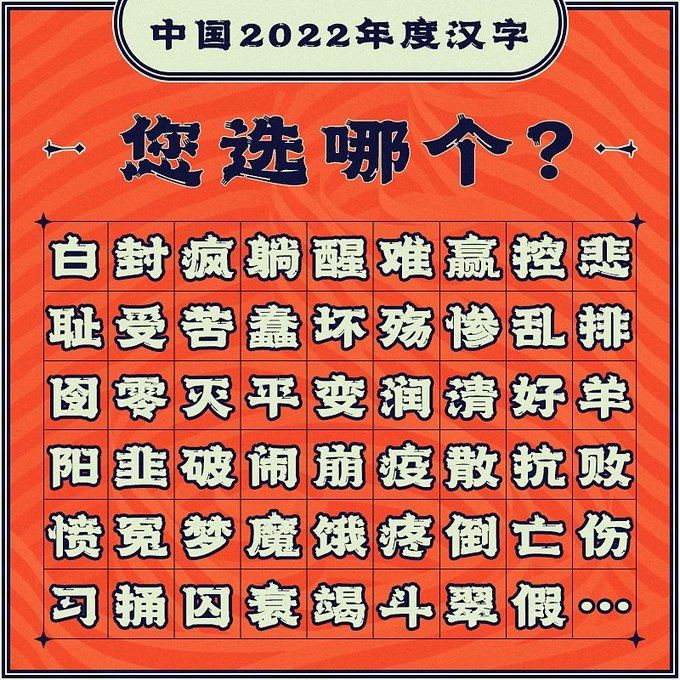

The officially orchestrated search for the word of the year provoked critical bloggers to weigh in. They pleaded for a word that was popular on the net but constantly deleted. It is called bai (白, white). In combinations such as “white revolution” or “white paper,” it has come to symbolize public protests against Beijing’s zero-Covid policies. The character yang (阳) also often appeared on the web. It means positive, that is, to be infected with Covid. Bloggers equated the sign with the identically pronounced sign yang (羊), to be a “sheep”. Don’t be sheep, they yell out to their readers. For two days, more than 100,000 users rejoiced over the online word cao (操, actually: to handle, to drive). Then even the censors realized that it was slang for the extended middle finger, with the subversive message to the party: “Screw you”.

Another blogger proposed two words for 2022 and 2023. For the past year, 封 (feng) “being trapped in lockdown” is a fitting expression, and for the coming year 疯 (feng) follows: “In 2023, we go completely nuts” (我一下选两,明年就省啦! 22年是 “封”,23年是 “疯).

But despite all the Internet mockery, the party never before exerted as much influence as it did this year on the selection of a word of the year. This was different at the beginning of Xi Jinping’s reign in 2013. Even then, the language commission had put Xi’s key political words at the top of its list of suggestions. Most notably, the characters meng (梦) for Xi’s dream of making China’s nation rich and strong, and lian (廉) for his purge campaign against corrupt officials, were considered words of the year for 2013. But 100,000 online voters voted differently. 42 percent chose the character fang (房) for house and 25 percent chose mai (霾) for smog. Their alternative words reflected the frustration that their dream of owning their own apartment was unaffordable and unattainable. Mai was used to protest against air pollution.

In 2013, publishing director Liu Zuochen of the Commercial Press, who led the word of the year project, told me: “We want our search for words and terms of the year to also give our government an important clue: What do the people want? What do they think? How did it feel this year?”

In 2009, the word bei (被) chosen by a majority as the word of the year had already given Beijing’s politicians food for thought. Bei is used as a passive character and stood for the citizens’ anger at feeling increasingly disempowered and controlled by an all-powerful party bureaucracy. They fought back linguistically: When Beijing’s official figures glossed over the extent of inflation, they responded with the passive form: “We have been price-stabilized.” When propaganda declared them happy Chinese, they said, “We were made happy.” At the time, even the official news agency Xinhua regarded the choice of bei as the word of the year as a latent signal for their “call for more freedom” and self-determination. South China’s Nanfang Dushibao newspaper commented that in a situation where open criticism and opposition are not tolerated, citizens use a word to “show awareness of wanting to exercise their civil rights.”

Today, Xi Jinping’s party would not only prevent such comments. It does not even let online voters pick China’s word of the year. Courageous citizens protest in a cat-and-mouse game with censors. Following the announcement of the official words of the year, bloggers posted on Wednesday under the headline “Which word would you choose?” 53 individual characters to choose from online. In combination with other words, they become critical terms that challenge Xi’s party rule. The list starts with the character for “white”, China’s new protest color.

Han Shangyou has been appointed CEO of Douyin. The 32-year-old is thus the youngest executive at the helm of the popular app. Douyin, like TikTok, the Western version of the short video app, is owned by Chinese tech giant ByteDance. Han joined the Beijing-based company in 2016. Previously, he was responsible for local services and the open developer platform at Douyin.

Lu Weibing will become president of device and smartphone manufacturer Xiaomi. He will succeed Wang Xiang effective December 30, the company’s chairman and founder Lei Jun announced Thursday. Two co-founders, Hong Feng and Wang Chuan, will also retire from the company’s day-to-day operations, Lei said in his statement. Lu, 46, most recently held the positions of president of the China region and head of the international division.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Backlit by the setting sun, a flock of cranes passes over Poyang Lake in Nanchang, eastern Jiangxi Province. The largest freshwater lake in China is an important wintering site for migratory birds. This year, it has been partially dried up by droughts. Chinese wildlife conservationists have therefore joined forces to help the animals with water and food. In China, the crane is traditionally considered a symbol of wisdom and long life.