Death is probably a topic that everyone around the world prefers to avoid. It is usually not for us to decide how we leave this life – be it peacefully in our sleep or after a long illness. In some countries, it is possible to avoid extreme pain and suffering to the very end thanks to assisted dying. Shenzhen has now become the first Chinese city to enshrine living will in law. This reignites the debate about euthanasia, as Ning Wang reports. Shenzhen could become a pilot project for authorities to analyze how the issue is received by the people and how the healthcare system can handle it. In any case, the new law gives citizens some control over the last decision in life.

The Chinese government has recently displayed the impression of absolute control in the domestic private sector. Tech companies have been reprimanded and fined, and IPOs have been temporarily suspended. Ride-hailing service DiDi is facing a billion-dollar fine, according to insiders. Many observers deemed the measures part of a new trend toward more state control over the economy. However, a study by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) paints a different picture. The notion that the private sector is being kept down is unfounded in light of the figures cited there, writes Frank Sieren, who took a closer look at the study. Overall revenues of private companies have risen steadily over the past ten years, while the share of companies controlled by the state has declined significantly. However, the fact that the freedom of the private sector has tight limits is proven by the party cells that became mandatory in every company under Xi Jinping. After all, private enterprise means something different in China than it does in the West.

It is a milestone: Shenzhen will allow terminally ill patients the choice of refusing life-saving treatment by law to protect their right to a dignified death. The city has passed a new law that is set to enter into force at the beginning of 2023. “When patients are at the final stage of an incurable disease or at the end of their life, medical agencies should respect the indications of their living will,” states the revised medical regulation published at the end of June.

Leading state media such as the Global Times also reported positively on this bill in their English editions. It is described as “pioneering” and would break through “traditional views”. It was also called “an important opportunity for public education about life and death”.

Reactions on social media about the law, on the other hand, were very mixed. Supporters believe that the plans show greater respect for human rights. While opponents see the risk that terminally ill patients could be forced by their families to refrain from further treatment out of fear of high medical costs. On Weibo, one doctor hailed the announcement as “absolutely necessary” to reduce patient suffering. The doctor also touches on the issue of euthanasia.

The Chinese public debated euthanasia since the 1980s. At that time, a program on the topic was broadcast on central and popular radio. The term 安乐死 – AnLeSi (peace, joy and dying) was even coined for euthanasia. A discussion initially held in academic circles found its way to the public after Deng Yingchao, wife of the late Premier Zhou Enlai, professed in a public letter in 1987, “I see euthanasia as proper point of dialectical materialism”. Her last will stated that no medical intervention should be performed if that was the only way to keep her alive. Her husband Zhou Enlai died in 1976 as a result of bladder cancer. Allegedly, Mao Zedong ordered doctors in 1972 to keep Zhou’s illness a secret from the couple at first. Zhou probably had a high chance of recovery if the cancer had been treated immediately.

In 1998, the issue was again hotly debated by Chinese experts in medicine, law and ethics. The consensus was that, in addition to the legal and medical issues, the associated sociological problems would also have to be solved. The unanswered questions were: Is euthanasia ethically justifiable? What social value does it have? Are legal regulations necessary? Since then, opinion polls have shown that a large number of respondents were in favor of anchoring assisted dying in law.

The responsible bodies in the Communist Party are at a crossroads. The issue holds many unknown risks. The decision now made by the city of Shenzhen respects the individual’s right to self-determination about what medical treatments he or she wants to receive at the end of life. By doing so, the city joins a practice already implemented in most industrialized countries.

The law in Shenzhen could also be seen as a test run. The central government will take a close look at its implementation. What problems will it cause in the healthcare system? Where are the legal pitfalls?

However, many health experts see little chance of the idea of living wills will reach the consciousness of the population. According to the Beijing Living Will Promotion Association, only about 50,000 people have signed a living will since 2011. The organization is advocating for legislation on living wills. “In addition to limited awareness, the traditional mindset of valuing life and neglecting death prevents people from accepting ‘progressive’ life choices,” the association states.

Moreover, it is unclear to what extent doctors and hospital staff must comply with living wills. “It is not mandatory to follow the advance directives,” Chen Wenchang, senior partner at Jiachuan Law Firm in Beijing, told Sixth Tone. But the new Shenzhen regulation could help “promote the concept of a dignified death nationwide”.

The new regulation in Shenzhen could also ease the burden on medical staff. “Doctors are usually under enormous ethical and emotional pressure to perform life-saving measures, even though they often have little chance of success,” he said. A living will protects medical professionals from lawsuits filed by a patient’s family. Collaboration: Renxiu Zhao.

China’s private companies have faced a slew of regulatory restrictions in 2021. Tech giants like Alipay and DiDi were put in their place. For the most part, the new rules have made sense, as they were designed to prevent monopolies and cartels. In the real estate sector, they were intended to ensure that companies did not incur excessive debt and also to create affordable housing. The methods of implementation, however, were crude. And without much civil society debate, companies were confronted with a new set of rules virtually overnight. IPOs had to be canceled, and legal action was ruled out for the time being. Many observers saw the measures as part of a new trend toward more state power over the economy, just as the Xi Jinping era is generally considered synonymous with greater state dominance.

However, the impression that the Chinese private sector is more oppressed than ever is false. In fact, a study conducted by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) reveals the contrary: China’s largest private companies are expanding faster than state-owned enterprises.

In absolute numbers, as well as measured by revenues or – in the case of listed companies – market value, privately owned companies have grown significantly since Xi Jinping took office in 2011 – even though the public sector still dominates.

The Peterson Institute has analyzed the revenues of Chinese companies from the Fortune Global 500 ranking and the largest companies by market capitalization. It shows that the revenue of privately held Chinese companies in 2011 was $104 billion. That is not even four percent of the combined revenue of all companies from the People’s Republic. In other words, state-owned enterprises account for the biggest share. Ten years later, the private sector’s share of the total revenue was already at 19 percent.

As for the market value of the largest listed companies, the private sector’s share of the 100 largest listed Chinese companies was only 8 percent at the end of 2010, but exceeded the 50 percent threshold in 2020. In 2021, the ratio declined only slightly to 48 percent due to government intervention. So the argument that the private sector is being prevented from expanding is hardly tenable in light of these numbers.

The relative share of companies controlled by the state through majority or minority stakes has also declined significantly over the past decade. What is often referred to as state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China are not necessarily fully or even majority owned by the Chinese state, as the authors of the Peterson study point out. Many SOEs are joint ventures of state and private owners. They are somewhere between state-owned and private, and it is very difficult to determine whether they are ultimately privately run or state-owned. In the automotive industry, for example, major manufacturers had long operated joint ventures where they only owned a 49 percent stake, yet these companies were predominantly market-driven. Another special case: State-owned companies have listed subsidiaries that dictate day-to-day business.

Since the start of the reform and opening-up policy of the late 1970s, China’s economy has grown spectacularly, with the bulk of the expansion attributed to the dynamism of the private sector. While only 15 Chinese companies were in the Fortune ranking in 2005, it was already 130 in 2021.

The advance of the private sector in China’s largest enterprises does not appear to be the result of long-term planning or top-down decisions, but rather a bottom-up dynamic. China’s largest enterprises have been virtually non-privatized, nor has the state made any effort to give the private sector a comparative advantage. On the contrary, President Xi Jinping declared in 2016 that state-owned enterprises must become “stronger, better, and larger” while simultaneously supporting the private sector.

Xi’s demand: China’s state-owned enterprises must prove themselves in a private-sector environment and hold their own in international business: One such example is state-owned port operator China Merchants Ports. It operates 30 percent of China’s ports and 68 ports in 27 countries. This includes the largest port in Brazil, and the largest port in Africa, currently under construction in Tanzania. But China Merchant Ports also has stakes in American ports in Houston and Miami, or ports in Le Havre and Marseille, France.

Private companies are generally more dynamic and profitable than the public sector. But the exceptions among state-owned enterprises should not be overlooked either. The big trend is what China scholar Nicholas R. Lardy called the “displacement of SOEs” by private-sector companies and aptly summarized in the book “Markets over Mao” more than ten years ago.

What is unusual in China is that CP cells were installed in private companies. Here, too, the effects are ambivalent. A party secretary can use his contacts to ensure that a private company progresses better by lobbying the government. But he can also harass management and throw obstacles in its path. The data suggest that this is rather the exception. But what is irritating is that party officials have the legal power to act in private companies in the first place.

The driving force behind the great privatization trend is simple. China wants to become an economic superpower, and that can only happen with internationally competitive companies. This is especially true in Internet and e-commerce, electronics, electric cars, batteries, steel, consumer goods and services, pharmaceuticals and life science companies. Some of China’s largest construction companies are also privately held, although the real estate sector has recently been battered by the financial woes of Evergrande and other players. In contrast, financial services, telecommunications, energy, and transportation continue to be dominated by state-owned enterprises.

But the growth of large companies in state-dominated sectors has been comparatively less rapid. Measured in terms of market value, some large companies in the telecommunications and energy sectors have actually lost value in absolute numbers. They have been surpassed by private companies.

According to a media report, China wants to prevent the publication of a UN report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang. In a letter to diplomats in Geneva, the publication of the report by the UN Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, was opposed, Reuters reported, citing insight into the letter. The move was confirmed by diplomats from three countries who received the letter.

Reuters reports that China has been trying since late June to rally support for keeping the report under wraps. The letter was said to be China’s way of soliciting support among diplomatic missions in Geneva. “The assessment (on Xinjiang), if published, will intensify politicization and bloc confrontation in the area of human rights, undermine the credibility of the OHCHR (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights), and harm the cooperation between OHCHR and member states,” the letter said, referring to Bachelet’s office.

It was at first unclear whether Bachelet’s office had also received the letter. An OHCHR spokesperson refused to comment on the matter. However, he said it was standard practice to share a copy of the report with the relevant government, in this case China, for comment before publication. Human rights groups accuse Beijing of abuses against the Uyghur people of Xinjiang, including the mass use of forced labor in internment camps. China rejects the allegations (China.Table reported). niw

German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock is promoting closer relations with Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. This would reduce Germany’s dependencies on China, Baerbock said in an interview with The Pioneer portal. In the interview, she also criticized the human rights situation in China and poor conditions for some German companies, such as forced disclosure of business secrets. However, she saw a complete reshoring to Europe as hardly feasible. Taiwan, South Korea and Japan could be alternative options for production.

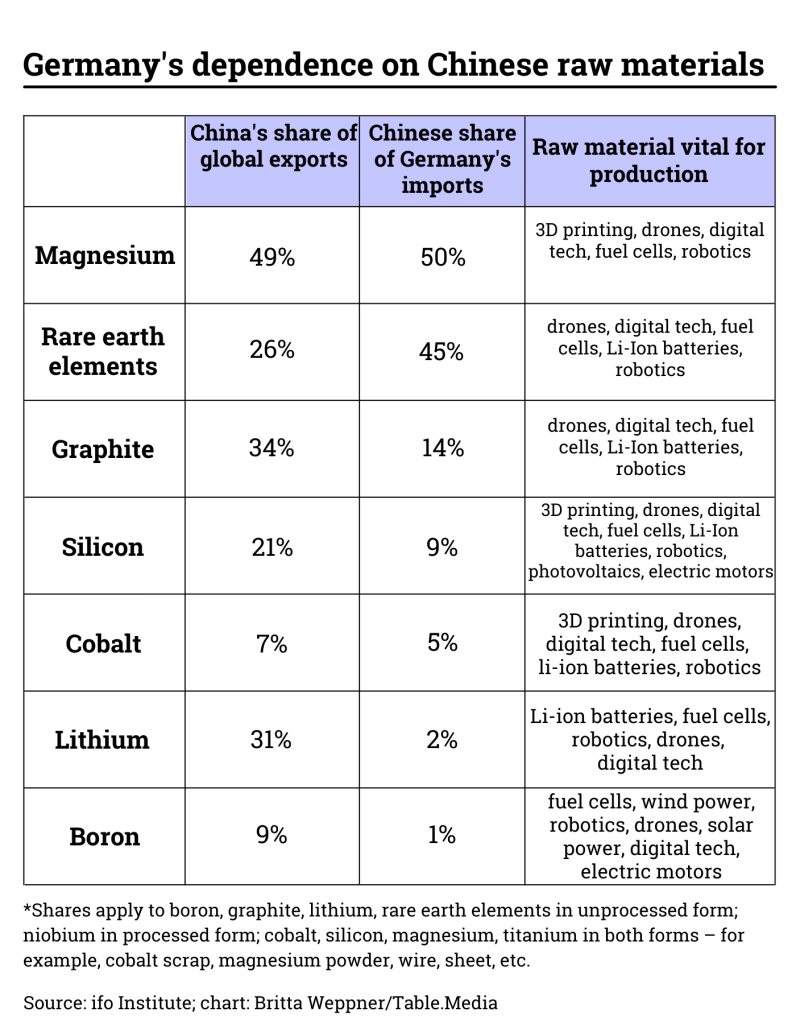

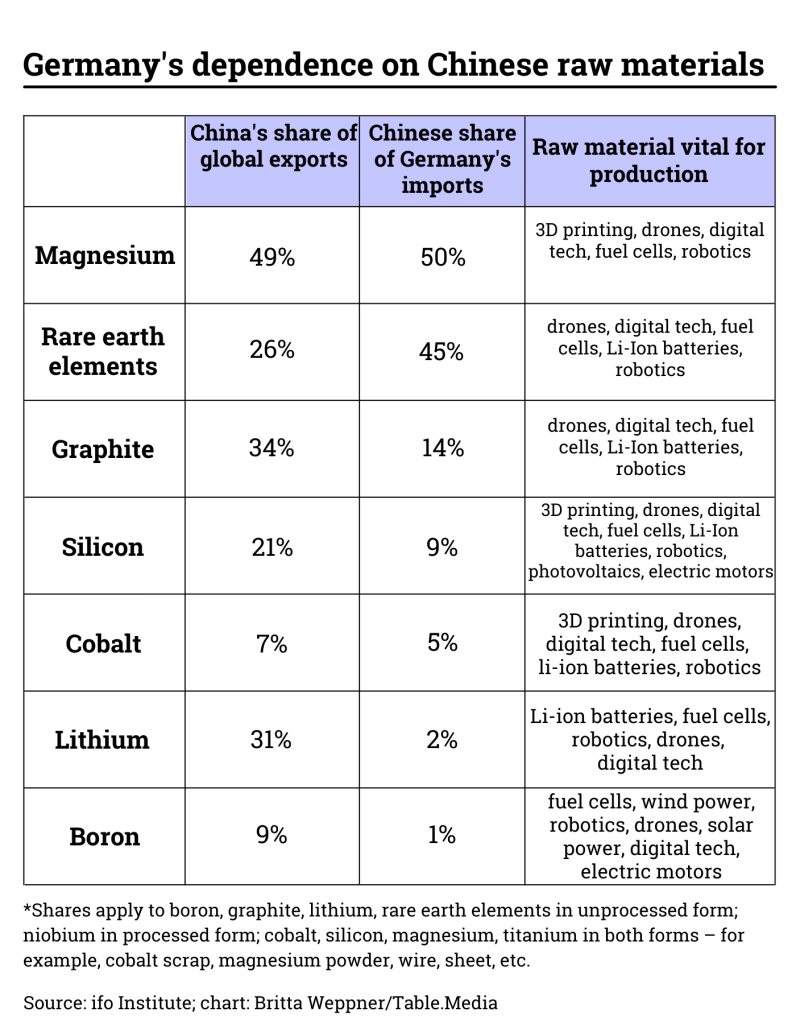

Germany and the EU countries are dependent on raw materials and intermediate goods from China in many areas. For rare earth elements and magnesium, Chinese imports each account for over 50 percent of Germany’s imports (China.Table reported). There is also a critical dependence on solar cells, printed circuit boards and medical goods. Most recently, German President Frank Steinmeier and Chancellery State Secretary Joerg Kukies warned of excessive dependence on rare earth elements from China. nib

In its annual report on human trafficking, the US State Department has condemned forced labor in China’s “New Silk Road”. Forced labor is the “hidden cost” of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the department said. Some New Silk Road projects involve violations such as:

The report claims that the relevant authorities in China do not have sufficient oversight of working conditions and fail to adequately prevent abuses. Foreign embassies have neglected to help exploited workers, according to the State Department. The ministry also sees the governments of host countries where BRI projects are implemented as responsible in this regard. They should inspect BRI construction sites more frequently and better protect exploited workers.

Allegations of human rights violations as part of the New Silk Road are not new. Last year, the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre compiled 679 allegations against China and its companies in a study (China.Table reported). nib

Russia remained the largest supplier of crude oil to the People’s Republic in June. Chinese importers took advantage of the price discount on Russian oil due to Western sanctions and reduced more expensive imports from Saudi Arabia, Reuters reported. China imported an average of 1.77 million barrels per day from Russia in June. That is slightly less than in May, but significantly exceeds imports from Saudi Arabia (1.23 million barrels per day). In year-to-date deliveries, Saudi Arabia is still slightly ahead of Russia. However, since the start of the Ukraine war, Russia has caught up. Accordingly, China is a beneficiary of the war.

LNG imports from Russia also surged. In the first half of the year, they amounted to 2.36 million metric tons – an increase of 30 percent compared to the same period last year. This contrasts with a 21 percent decline in Russia’s total LNG imports compared to the same period last year. Analysis firm Wood Mackenzie forecasts that China’s LNG imports will drop by 14 percent this year to 69 million tons. Japan would thus return to being the world’s largest importer.

Overall, China’s oil imports fell to a four-year low in June, with Covid lockdowns and low economic growth as the main causes. While China continues to purchase oil from Iran, the People’s Republic avoids imports from Venezuela. Both countries are under US sanctions. nib

Chemical company BASF has granted final approval for the construction of its planned Zhanjiang Verbund site in southern China’s Guangdong province. The company also announced that construction work is now focusing on the core, which includes a steam cracker and facilities for the production of petrochemicals and intermediates.

BASF will invest up to €10 billion in the construction of the new Verbund site until 2030. BASF began construction in 2020 and plans to finish it by the end of 2022. “The smart Verbund site will form a solid foundation for a world-class industrial cluster in Zhanjiang,” Dr. Stephan Kothrade, President Asia Pacific Functions, President and Chairman Greater China, BASF announced at the groundbreaking ceremony at the time. Once completed, Zhanjiang will be BASF’s third largest Verbund after Ludwigshafen and Antwerp. niw/rtr

It’s nine in the morning, but Michael Clauß kindly declines a cup of coffee. He already had two breakfast appointments, says the German EU ambassador, so his caffeine needs are covered. The next appointment is already scheduled, and it will take Clauß to the so-called confessional. The cabinet of Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is once again sounding out in small groups what concerns the member states have about the new sanctions against Russia.

Brussels’ political scene goes on its obligatory summer break in August, despite war and crises. Crisis is now piling up on crisis, and Clauß is right in the middle of the EU’s political containment efforts. He knows the EU business like no one else. The 60-year-old has managed Germany’s past two Council presidencies, in 2020 as Ambassador, and in 2007 as Deputy Head of Department at the Federal Foreign Office. He accompanied the process of drafting a European constitution as head of the German Convention Secretariat, from the start in 2002 to its bitter end – the rejection by France and the Netherlands.

However, Clauß imagined things quite differently. After his first years in the foreign office, he was supposed to become ambassador to Sierra Leone. “My wife and I found the adventure very appealing,” he says. A few hours before his departure, however, there was a coup in the West African country, and the German mission in the capital, Freetown, had to be evacuated. So another use had to be found for Clauß – as an embassy counselor at the EU representation. “The fact that I was sent to Brussels instead was pure coincidence,” he says.

At first, Clauß was not particularly enthusiastic about it. He knew Belgium from his school days, and his father was a Bundeswehr officer stationed for a time at the NATO High Command in Mons. Clauß, however, wanted to experience distant countries. That was one of the reasons why, after two years as a regular soldier, he decided to join the diplomatic service – and not to join the army, where his father had made it to the rank of four-star general.

But it ended up being Brussels instead of Freetown. This was followed by 14 years at the headquarters in Werderscher Markt, most recently as Head of the European Department. In 2013, it was time for a change of scenery, says Clauß: He became ambassador to China. “It’s healing and helpful to look at things from the outside,” he says. “Looking from Beijing, Brussels is not the navel of the world.” Compared to the enormous dynamism in China, he says, processes in Europe are often cumbersome and bureaucratic.

It is difficult for foreigners to look behind the curtains of the Chinese system in Beijing. Contact with Western diplomats is unwelcome for CP cadres. His wife, however, gave Clauß insights that he otherwise would have missed. Through her, he gained access to the Chinese elite, members of the so-called Revolutionary Families: sons, daughters and grandchildren of Mao’s former comrades-in-arms, without an official party position but influential and well-informed nonetheless. Many of them were educated at elite US universities and therefore speak English very well.

“The women met every now and then on weekends, and we men just tagged along,” Clauß says. In this context, it was possible to speak quite openly with each other. “That opened the door for me to a shielded world. And it helped to put the official information in perspective.”

Since then, he no longer harbors any illusions about how the system works or its claim to power. “China derives great self-confidence from its development and is questioning our political and social system,” he says. The CCP is becoming increasingly repressive and is trying to reshape the international order to its liking. For example, the Belt and Road Initiative would serve to establish a hierarchical relationship with other states, with Beijing at the top. “In Europe, it has not been seen for a long time that China is a systemic rival. It was important for me to convey here in Brussels that we need to shed this naiveté.”

By now, that message has sunk in. Clauß contributed to it after his transfer to Brussels in 2018, hand in hand with other China aficionados like Green Party MEP Reinhard Buetikofer. Meanwhile, the EU has launched a €300 billion counterpart to the New Silk Road. “Global Gateway has the potential to be a real alternative,” Clauß says. “But now we have to move forward, taking a value-based approach, but also a realistic one, to involve as many countries as possible.”

In Berlin, the diplomat is held in high esteem across party lines for his competence and objectivity, and the government coalition is also keeping him on board. Clauß has no party affiliation, something that is incompatible with his civil servant ethos. He tries to feed the insights gained in Brussels into the German government’s European policy coordination processes, for example, regarding the majority ratios in the Council and the European Parliament.

To shake off the stress, Clauß goes running every weekend for many, many kilometers, and sometimes he even gets on his racing bicycle. During the week, he tries to keep an extra date in his calendar free for it. “I’m a long-distance runner, it’s a real passion,” he says. He needs the athletic balance for physical health, but also for mental hygiene.

Clauß has long since made peace with the fact that his career has taken him to the EU’s jungle of regulations instead of the African rainforest. “Brussels may not be as exotic,” he says, “but it’s also adventurous here at times.” Till Hoppe

Fan Xinhe is the new press contact of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China. She is based in the Chamber’s Beijing office.

Li Jian was appointed as the new Chinese ambassador to Algeria, replacing Li Lianhe.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Bridges, roads, airports – to boost growth, China once again relies on an old recipe: infrastructure expansion. This new rail bridge over the Lancang River now connects China’s rail network to the city of Baoshan, home to two million people.

Death is probably a topic that everyone around the world prefers to avoid. It is usually not for us to decide how we leave this life – be it peacefully in our sleep or after a long illness. In some countries, it is possible to avoid extreme pain and suffering to the very end thanks to assisted dying. Shenzhen has now become the first Chinese city to enshrine living will in law. This reignites the debate about euthanasia, as Ning Wang reports. Shenzhen could become a pilot project for authorities to analyze how the issue is received by the people and how the healthcare system can handle it. In any case, the new law gives citizens some control over the last decision in life.

The Chinese government has recently displayed the impression of absolute control in the domestic private sector. Tech companies have been reprimanded and fined, and IPOs have been temporarily suspended. Ride-hailing service DiDi is facing a billion-dollar fine, according to insiders. Many observers deemed the measures part of a new trend toward more state control over the economy. However, a study by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) paints a different picture. The notion that the private sector is being kept down is unfounded in light of the figures cited there, writes Frank Sieren, who took a closer look at the study. Overall revenues of private companies have risen steadily over the past ten years, while the share of companies controlled by the state has declined significantly. However, the fact that the freedom of the private sector has tight limits is proven by the party cells that became mandatory in every company under Xi Jinping. After all, private enterprise means something different in China than it does in the West.

It is a milestone: Shenzhen will allow terminally ill patients the choice of refusing life-saving treatment by law to protect their right to a dignified death. The city has passed a new law that is set to enter into force at the beginning of 2023. “When patients are at the final stage of an incurable disease or at the end of their life, medical agencies should respect the indications of their living will,” states the revised medical regulation published at the end of June.

Leading state media such as the Global Times also reported positively on this bill in their English editions. It is described as “pioneering” and would break through “traditional views”. It was also called “an important opportunity for public education about life and death”.

Reactions on social media about the law, on the other hand, were very mixed. Supporters believe that the plans show greater respect for human rights. While opponents see the risk that terminally ill patients could be forced by their families to refrain from further treatment out of fear of high medical costs. On Weibo, one doctor hailed the announcement as “absolutely necessary” to reduce patient suffering. The doctor also touches on the issue of euthanasia.

The Chinese public debated euthanasia since the 1980s. At that time, a program on the topic was broadcast on central and popular radio. The term 安乐死 – AnLeSi (peace, joy and dying) was even coined for euthanasia. A discussion initially held in academic circles found its way to the public after Deng Yingchao, wife of the late Premier Zhou Enlai, professed in a public letter in 1987, “I see euthanasia as proper point of dialectical materialism”. Her last will stated that no medical intervention should be performed if that was the only way to keep her alive. Her husband Zhou Enlai died in 1976 as a result of bladder cancer. Allegedly, Mao Zedong ordered doctors in 1972 to keep Zhou’s illness a secret from the couple at first. Zhou probably had a high chance of recovery if the cancer had been treated immediately.

In 1998, the issue was again hotly debated by Chinese experts in medicine, law and ethics. The consensus was that, in addition to the legal and medical issues, the associated sociological problems would also have to be solved. The unanswered questions were: Is euthanasia ethically justifiable? What social value does it have? Are legal regulations necessary? Since then, opinion polls have shown that a large number of respondents were in favor of anchoring assisted dying in law.

The responsible bodies in the Communist Party are at a crossroads. The issue holds many unknown risks. The decision now made by the city of Shenzhen respects the individual’s right to self-determination about what medical treatments he or she wants to receive at the end of life. By doing so, the city joins a practice already implemented in most industrialized countries.

The law in Shenzhen could also be seen as a test run. The central government will take a close look at its implementation. What problems will it cause in the healthcare system? Where are the legal pitfalls?

However, many health experts see little chance of the idea of living wills will reach the consciousness of the population. According to the Beijing Living Will Promotion Association, only about 50,000 people have signed a living will since 2011. The organization is advocating for legislation on living wills. “In addition to limited awareness, the traditional mindset of valuing life and neglecting death prevents people from accepting ‘progressive’ life choices,” the association states.

Moreover, it is unclear to what extent doctors and hospital staff must comply with living wills. “It is not mandatory to follow the advance directives,” Chen Wenchang, senior partner at Jiachuan Law Firm in Beijing, told Sixth Tone. But the new Shenzhen regulation could help “promote the concept of a dignified death nationwide”.

The new regulation in Shenzhen could also ease the burden on medical staff. “Doctors are usually under enormous ethical and emotional pressure to perform life-saving measures, even though they often have little chance of success,” he said. A living will protects medical professionals from lawsuits filed by a patient’s family. Collaboration: Renxiu Zhao.

China’s private companies have faced a slew of regulatory restrictions in 2021. Tech giants like Alipay and DiDi were put in their place. For the most part, the new rules have made sense, as they were designed to prevent monopolies and cartels. In the real estate sector, they were intended to ensure that companies did not incur excessive debt and also to create affordable housing. The methods of implementation, however, were crude. And without much civil society debate, companies were confronted with a new set of rules virtually overnight. IPOs had to be canceled, and legal action was ruled out for the time being. Many observers saw the measures as part of a new trend toward more state power over the economy, just as the Xi Jinping era is generally considered synonymous with greater state dominance.

However, the impression that the Chinese private sector is more oppressed than ever is false. In fact, a study conducted by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) reveals the contrary: China’s largest private companies are expanding faster than state-owned enterprises.

In absolute numbers, as well as measured by revenues or – in the case of listed companies – market value, privately owned companies have grown significantly since Xi Jinping took office in 2011 – even though the public sector still dominates.

The Peterson Institute has analyzed the revenues of Chinese companies from the Fortune Global 500 ranking and the largest companies by market capitalization. It shows that the revenue of privately held Chinese companies in 2011 was $104 billion. That is not even four percent of the combined revenue of all companies from the People’s Republic. In other words, state-owned enterprises account for the biggest share. Ten years later, the private sector’s share of the total revenue was already at 19 percent.

As for the market value of the largest listed companies, the private sector’s share of the 100 largest listed Chinese companies was only 8 percent at the end of 2010, but exceeded the 50 percent threshold in 2020. In 2021, the ratio declined only slightly to 48 percent due to government intervention. So the argument that the private sector is being prevented from expanding is hardly tenable in light of these numbers.

The relative share of companies controlled by the state through majority or minority stakes has also declined significantly over the past decade. What is often referred to as state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China are not necessarily fully or even majority owned by the Chinese state, as the authors of the Peterson study point out. Many SOEs are joint ventures of state and private owners. They are somewhere between state-owned and private, and it is very difficult to determine whether they are ultimately privately run or state-owned. In the automotive industry, for example, major manufacturers had long operated joint ventures where they only owned a 49 percent stake, yet these companies were predominantly market-driven. Another special case: State-owned companies have listed subsidiaries that dictate day-to-day business.

Since the start of the reform and opening-up policy of the late 1970s, China’s economy has grown spectacularly, with the bulk of the expansion attributed to the dynamism of the private sector. While only 15 Chinese companies were in the Fortune ranking in 2005, it was already 130 in 2021.

The advance of the private sector in China’s largest enterprises does not appear to be the result of long-term planning or top-down decisions, but rather a bottom-up dynamic. China’s largest enterprises have been virtually non-privatized, nor has the state made any effort to give the private sector a comparative advantage. On the contrary, President Xi Jinping declared in 2016 that state-owned enterprises must become “stronger, better, and larger” while simultaneously supporting the private sector.

Xi’s demand: China’s state-owned enterprises must prove themselves in a private-sector environment and hold their own in international business: One such example is state-owned port operator China Merchants Ports. It operates 30 percent of China’s ports and 68 ports in 27 countries. This includes the largest port in Brazil, and the largest port in Africa, currently under construction in Tanzania. But China Merchant Ports also has stakes in American ports in Houston and Miami, or ports in Le Havre and Marseille, France.

Private companies are generally more dynamic and profitable than the public sector. But the exceptions among state-owned enterprises should not be overlooked either. The big trend is what China scholar Nicholas R. Lardy called the “displacement of SOEs” by private-sector companies and aptly summarized in the book “Markets over Mao” more than ten years ago.

What is unusual in China is that CP cells were installed in private companies. Here, too, the effects are ambivalent. A party secretary can use his contacts to ensure that a private company progresses better by lobbying the government. But he can also harass management and throw obstacles in its path. The data suggest that this is rather the exception. But what is irritating is that party officials have the legal power to act in private companies in the first place.

The driving force behind the great privatization trend is simple. China wants to become an economic superpower, and that can only happen with internationally competitive companies. This is especially true in Internet and e-commerce, electronics, electric cars, batteries, steel, consumer goods and services, pharmaceuticals and life science companies. Some of China’s largest construction companies are also privately held, although the real estate sector has recently been battered by the financial woes of Evergrande and other players. In contrast, financial services, telecommunications, energy, and transportation continue to be dominated by state-owned enterprises.

But the growth of large companies in state-dominated sectors has been comparatively less rapid. Measured in terms of market value, some large companies in the telecommunications and energy sectors have actually lost value in absolute numbers. They have been surpassed by private companies.

According to a media report, China wants to prevent the publication of a UN report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang. In a letter to diplomats in Geneva, the publication of the report by the UN Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, was opposed, Reuters reported, citing insight into the letter. The move was confirmed by diplomats from three countries who received the letter.

Reuters reports that China has been trying since late June to rally support for keeping the report under wraps. The letter was said to be China’s way of soliciting support among diplomatic missions in Geneva. “The assessment (on Xinjiang), if published, will intensify politicization and bloc confrontation in the area of human rights, undermine the credibility of the OHCHR (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights), and harm the cooperation between OHCHR and member states,” the letter said, referring to Bachelet’s office.

It was at first unclear whether Bachelet’s office had also received the letter. An OHCHR spokesperson refused to comment on the matter. However, he said it was standard practice to share a copy of the report with the relevant government, in this case China, for comment before publication. Human rights groups accuse Beijing of abuses against the Uyghur people of Xinjiang, including the mass use of forced labor in internment camps. China rejects the allegations (China.Table reported). niw

German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock is promoting closer relations with Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. This would reduce Germany’s dependencies on China, Baerbock said in an interview with The Pioneer portal. In the interview, she also criticized the human rights situation in China and poor conditions for some German companies, such as forced disclosure of business secrets. However, she saw a complete reshoring to Europe as hardly feasible. Taiwan, South Korea and Japan could be alternative options for production.

Germany and the EU countries are dependent on raw materials and intermediate goods from China in many areas. For rare earth elements and magnesium, Chinese imports each account for over 50 percent of Germany’s imports (China.Table reported). There is also a critical dependence on solar cells, printed circuit boards and medical goods. Most recently, German President Frank Steinmeier and Chancellery State Secretary Joerg Kukies warned of excessive dependence on rare earth elements from China. nib

In its annual report on human trafficking, the US State Department has condemned forced labor in China’s “New Silk Road”. Forced labor is the “hidden cost” of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the department said. Some New Silk Road projects involve violations such as:

The report claims that the relevant authorities in China do not have sufficient oversight of working conditions and fail to adequately prevent abuses. Foreign embassies have neglected to help exploited workers, according to the State Department. The ministry also sees the governments of host countries where BRI projects are implemented as responsible in this regard. They should inspect BRI construction sites more frequently and better protect exploited workers.

Allegations of human rights violations as part of the New Silk Road are not new. Last year, the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre compiled 679 allegations against China and its companies in a study (China.Table reported). nib

Russia remained the largest supplier of crude oil to the People’s Republic in June. Chinese importers took advantage of the price discount on Russian oil due to Western sanctions and reduced more expensive imports from Saudi Arabia, Reuters reported. China imported an average of 1.77 million barrels per day from Russia in June. That is slightly less than in May, but significantly exceeds imports from Saudi Arabia (1.23 million barrels per day). In year-to-date deliveries, Saudi Arabia is still slightly ahead of Russia. However, since the start of the Ukraine war, Russia has caught up. Accordingly, China is a beneficiary of the war.

LNG imports from Russia also surged. In the first half of the year, they amounted to 2.36 million metric tons – an increase of 30 percent compared to the same period last year. This contrasts with a 21 percent decline in Russia’s total LNG imports compared to the same period last year. Analysis firm Wood Mackenzie forecasts that China’s LNG imports will drop by 14 percent this year to 69 million tons. Japan would thus return to being the world’s largest importer.

Overall, China’s oil imports fell to a four-year low in June, with Covid lockdowns and low economic growth as the main causes. While China continues to purchase oil from Iran, the People’s Republic avoids imports from Venezuela. Both countries are under US sanctions. nib

Chemical company BASF has granted final approval for the construction of its planned Zhanjiang Verbund site in southern China’s Guangdong province. The company also announced that construction work is now focusing on the core, which includes a steam cracker and facilities for the production of petrochemicals and intermediates.

BASF will invest up to €10 billion in the construction of the new Verbund site until 2030. BASF began construction in 2020 and plans to finish it by the end of 2022. “The smart Verbund site will form a solid foundation for a world-class industrial cluster in Zhanjiang,” Dr. Stephan Kothrade, President Asia Pacific Functions, President and Chairman Greater China, BASF announced at the groundbreaking ceremony at the time. Once completed, Zhanjiang will be BASF’s third largest Verbund after Ludwigshafen and Antwerp. niw/rtr

It’s nine in the morning, but Michael Clauß kindly declines a cup of coffee. He already had two breakfast appointments, says the German EU ambassador, so his caffeine needs are covered. The next appointment is already scheduled, and it will take Clauß to the so-called confessional. The cabinet of Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is once again sounding out in small groups what concerns the member states have about the new sanctions against Russia.

Brussels’ political scene goes on its obligatory summer break in August, despite war and crises. Crisis is now piling up on crisis, and Clauß is right in the middle of the EU’s political containment efforts. He knows the EU business like no one else. The 60-year-old has managed Germany’s past two Council presidencies, in 2020 as Ambassador, and in 2007 as Deputy Head of Department at the Federal Foreign Office. He accompanied the process of drafting a European constitution as head of the German Convention Secretariat, from the start in 2002 to its bitter end – the rejection by France and the Netherlands.

However, Clauß imagined things quite differently. After his first years in the foreign office, he was supposed to become ambassador to Sierra Leone. “My wife and I found the adventure very appealing,” he says. A few hours before his departure, however, there was a coup in the West African country, and the German mission in the capital, Freetown, had to be evacuated. So another use had to be found for Clauß – as an embassy counselor at the EU representation. “The fact that I was sent to Brussels instead was pure coincidence,” he says.

At first, Clauß was not particularly enthusiastic about it. He knew Belgium from his school days, and his father was a Bundeswehr officer stationed for a time at the NATO High Command in Mons. Clauß, however, wanted to experience distant countries. That was one of the reasons why, after two years as a regular soldier, he decided to join the diplomatic service – and not to join the army, where his father had made it to the rank of four-star general.

But it ended up being Brussels instead of Freetown. This was followed by 14 years at the headquarters in Werderscher Markt, most recently as Head of the European Department. In 2013, it was time for a change of scenery, says Clauß: He became ambassador to China. “It’s healing and helpful to look at things from the outside,” he says. “Looking from Beijing, Brussels is not the navel of the world.” Compared to the enormous dynamism in China, he says, processes in Europe are often cumbersome and bureaucratic.

It is difficult for foreigners to look behind the curtains of the Chinese system in Beijing. Contact with Western diplomats is unwelcome for CP cadres. His wife, however, gave Clauß insights that he otherwise would have missed. Through her, he gained access to the Chinese elite, members of the so-called Revolutionary Families: sons, daughters and grandchildren of Mao’s former comrades-in-arms, without an official party position but influential and well-informed nonetheless. Many of them were educated at elite US universities and therefore speak English very well.

“The women met every now and then on weekends, and we men just tagged along,” Clauß says. In this context, it was possible to speak quite openly with each other. “That opened the door for me to a shielded world. And it helped to put the official information in perspective.”

Since then, he no longer harbors any illusions about how the system works or its claim to power. “China derives great self-confidence from its development and is questioning our political and social system,” he says. The CCP is becoming increasingly repressive and is trying to reshape the international order to its liking. For example, the Belt and Road Initiative would serve to establish a hierarchical relationship with other states, with Beijing at the top. “In Europe, it has not been seen for a long time that China is a systemic rival. It was important for me to convey here in Brussels that we need to shed this naiveté.”

By now, that message has sunk in. Clauß contributed to it after his transfer to Brussels in 2018, hand in hand with other China aficionados like Green Party MEP Reinhard Buetikofer. Meanwhile, the EU has launched a €300 billion counterpart to the New Silk Road. “Global Gateway has the potential to be a real alternative,” Clauß says. “But now we have to move forward, taking a value-based approach, but also a realistic one, to involve as many countries as possible.”

In Berlin, the diplomat is held in high esteem across party lines for his competence and objectivity, and the government coalition is also keeping him on board. Clauß has no party affiliation, something that is incompatible with his civil servant ethos. He tries to feed the insights gained in Brussels into the German government’s European policy coordination processes, for example, regarding the majority ratios in the Council and the European Parliament.

To shake off the stress, Clauß goes running every weekend for many, many kilometers, and sometimes he even gets on his racing bicycle. During the week, he tries to keep an extra date in his calendar free for it. “I’m a long-distance runner, it’s a real passion,” he says. He needs the athletic balance for physical health, but also for mental hygiene.

Clauß has long since made peace with the fact that his career has taken him to the EU’s jungle of regulations instead of the African rainforest. “Brussels may not be as exotic,” he says, “but it’s also adventurous here at times.” Till Hoppe

Fan Xinhe is the new press contact of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China. She is based in the Chamber’s Beijing office.

Li Jian was appointed as the new Chinese ambassador to Algeria, replacing Li Lianhe.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Bridges, roads, airports – to boost growth, China once again relies on an old recipe: infrastructure expansion. This new rail bridge over the Lancang River now connects China’s rail network to the city of Baoshan, home to two million people.