De-risking is the name of the game when it comes to relations with the People’s Republic. Germany’s China strategy, which is only a few days old, also mentions minimizing risk as its main goal. But: “There are very different risks – and the concept of risk is not defined in the paper,” says economist and professor of China Business and Economics, Doris Fischer. “Here, the next step would have to be to create clarity first.” Finn Mayer-Kuckuk spoke with Fischer about how this could work, what the worst case for risk minimization would be, and what Germany can do to prepare.

Chinese exports declined in June. Imports also fell significantly. However, these developments should not deceive us, writes Frank Sieren. In international comparison, China’s balance of trade is still in a very good shape. Trade in the Chinese yuan is also gaining momentum.

The German government has presented its China strategy. Is the document suitable as a guideline for economic policy?

I was very skeptical about what kind of document it would be. It turned out much better than I feared, but I would still say that the word strategy does not apply in all respects.

Is it a useful policy paper, nonetheless?

There are clear guidelines in some areas on how the German government wants to act, but the authors had to leave the details open in many areas.

What would the actual implementation by the German government look like?

The central concept of the strategy paper is risk minimization. However, there are very different risks – and the paper does not define the concept of risk. Here, the next step would have to be to first create clarity.

What types of risk do you distinguish?

I see mainly investment risks, supply chain risks and political risks. Normal investment risks exist in all countries where companies are active. In fact, Chinese economic development is currently becoming more risky because the economy is not performing smoothly. There is a lack of demand. This factor also makes companies reconsider and look more at other markets. But whether they needed the discussion about the China strategy for this or not, that is hard to assess.

What about supply chain risks?

A prime example of this was the shipping accident in the Suez Canal, which cut Europe off from Asian goods for several days.

Or the pandemic.

Yes. If the supply chains are finely chiseled and also relatively dependent on one market, then shocks can occur. Then we are suddenly at risk. But that is only partly linked to China. In any case, China is not to blame. Here, every company must and had to clarify for itself: Am I adequately prepared for such irregularities? The industry is already thinking about the supply chain risk. The consensus here is “China plus one.”

This means that each supplied part is not only sourced from one country, but always from another supplier.

It can also be “China plus three.” The regional distribution of risk is a good risk management strategy. Actually, up to now, it should have been said that this is part of a good corporate strategy. However, under the conditions of globalization as we have experienced in the past 20 years, there was a tendency to rely solely on the cheapest suppliers and, moreover, on “just in time” deliveries. Another approach to reducing the risks is increased warehousing. However, companies also do not need a government strategy to understand this.

However, this process has already been underway since the pandemic at the latest, and company representatives assure us that they have the issue at the top of their agenda. Where does the strategy set new impulses?

This is where the third risk comes into play, the potential for using dependencies politically. In the past, we used to say: If trade relations are intensive, that should actually be a guarantee for peaceful relations. But now we have learned that trade dependency can also be used strategically to achieve foreign policy goals through economic pressure.

Here, politicians are now openly discussing the risk of an invasion of Taiwan with catastrophic repercussions on trade relations.

That would be the worst case.

What can Germany do to prepare?

We must be clear to what extent we can minimize these risks at all. There are also scenarios in which China abuses its market power to exert pressure against a single country. The incident with Lithuania, when China froze trade with the country, was a wake-up call in this respect. Before that, the problems that other countries like Australia had with China were not really taken seriously. Now there is a greater awareness of these risks. In addition, the US is constantly intensifying its conflict with China.

If we look again at the big picture and the government’s wish to eliminate these risks as far as possible. How can that be achieved?

That is almost impossible. Even if we only trade with closely allied countries, they, in turn, have their own China risks. Germany and the EU cannot become self-sufficient either without giving up a great deal of wealth. We have to bear these risks to some extent. De-risking in the sense of reducing risks is sensible, but we will not be able to eliminate the risks. As an exporting country, we are a risk society and will continue to be one.

Are politicians perhaps even creating new risks in the pursuit of security?

The more we pursue anti-China policies, the more we push the Chinese government into this corner. And that’s why I’m very wary of always painting the worst-case scenario on the wall.

However, companies would then also have to prepare for this eventuality.

We cannot expect companies to prepare in detail for a possible war between China and Taiwan in three, five or ten years, or not at all. They would have to prepare for entirely different scenarios, for example, in the Middle East, Africa – or the United States.

Do companies read the China strategy?

In practice, entrepreneurs and executives probably have other concerns. Many industries are currently mainly concerned with whether their products are competitive. One company representative told me that they had looked at it, but it is not really important to them.

So not much will change in the short term?

We are in an economy-political loop in which we are and remain dependent on goods from China, and China is in a loop in which it remains dependent on exports. Despite assurances to the contrary, we cannot easily break free.

How is this strategy being received in China?

Actually, you can explain a risk strategy to the Chinese quite well. For 20 years, China has done nothing but deal with the risks for the Chinese economy and society, with the conventional risks, but above all, with the non-conventional risks. It was also positively registered in Beijing that it did not turn out to be a pure anti-China strategy.

Doris Fischer is a professor of China Business and Economics at the Julius-Maximilians-University of Wuerzburg. She has a Sinology and Business Administration background and holds a Ph.D. in Economics. Her areas of research include China’s economic and industrial policy. She is currently also the Vice President for Internationalization and Alumni at the University of Wuerzburg.

Chinese exports contracted by more than 12 percent year-on-year in June, the biggest decline since February 2020. Imports also fell significantly. This is mainly due to the fact that major trading partners such as the US, EU and Japan are buying less from China. Exports fell by 12.4 percent year-on-year to around 285 billion US dollars. The imports of the second-largest economy fell by 6.8 percent to 215 billion dollars. Foreign trade had already slowed down in the previous months. That sounds alarming.

But Beijing also has reason to celebrate: For the first time in its history, China’s trade volume exceeded the 20 trillion yuan mark during the first half of this year. That is the equivalent of 2.8 trillion US dollars. In this period, despite the weakening domestic economy and low international demand, the trade volume has increased by 400 billion yuan (about 50 billion euros), which is roughly equivalent to the value of all the roughly three million Chinese cars exported in 2022.

How China is actually performing internationally despite a year-on-year trade decline is revealed when comparing China’s trade balance with that of other countries.

The figures for the first half of the year are not yet available everywhere. But the direction is clear. Although China’s trade is not developing as expected, the country still generated a trade surplus of well over 60 billion US dollars during the first six months of 2023. In June, it was even over 70 billion US dollars. This means China is doing very well in international comparison.

The USA, China’s largest competitor, is again running a high trade deficit this year. In the first half of the year, it is already at around 70 billion US dollars per month. Japan’s monthly deficit is the equivalent of about 50 billion US dollars, India’s is around 17 billion US dollars. The EU’s trade balance at least breaks even. This means that the EU does not earn any money, but does not make any trade losses either.

And the Germans at least generate a surplus of around 15 billion US dollars. A comparison with the figures from 2022 shows that there is no trend reversal in sight: China had a record surplus of just under 877 billion US dollars. A growth of twelve percent. The US had a record deficit of 945 billion US dollars. The EU came in at minus 432 billion. Japan had a deficit of 150 billion US dollars. In India, it was minus 122 billion US dollars. And Germany had a surplus of just under 80 billion euros in 2022. The only exception in the first half of the year was the EU, which at least had a neutral trade balance.

What does this mean for international competition? Like with a business or a household, it is always better to earn more than you spend. The only two countries mentioned where this is the case are China and Germany. For other countries, in order to pay the deficit, a country usually needs foreign loans. And that is why foreign debt correlates with deficits. This is why China has the lowest external debt. These are measured as a percentage of GDP.

The leader is Germany with 156 percent, followed by the EU with 117 percent. The USA and Japan are at around 100 percent. India at 20 percent. China comes out best, with an external debt-to-GDP ratio of 13 percent. At the same time, China, together with Japan, is the largest creditor of the United States. Overall, it can be said that the more a country makes from trade and the less external debt it has, the more independent it is both economically and politically.

Because debt hides a currency risk: Everything that a country has to buy on the global market has to be paid for in a foreign currency. External debt in return is also denominated in a foreign currency, mostly US dollars. Even in leading exporting nations, most of the GDP is generated in the respective national currency. In China, that is 62 percent. In Germany, it is a good 50 percent.

If a country experiences an economic crisis, many international investors sell the respective currency which causes the exchange rate to fall. The crisis country now receives fewer US dollars for its own currency. This increases the US dollar debt. The indebted country then generally starts to print money. As a result, prices go up and the inflationary spiral begins. The currency becomes weaker and weaker, the debts grow heavier and heavier. Countries are at the mercy of international pressure. The last time this happened on a large scale in Asia was in 1997 during the Asian crisis.

So the impression is: Regarding such a development, China, with its low debt, is in the best position and the USA is in the worst position. However, this is not entirely true. For there is a big difference between China and the United States: The US dollar is so strong that it cannot be put under pressure by any other currency, no matter how heavy the burden of debt may be. On the contrary: In times of global crisis, the US dollar grows stronger because many exchange their money for the strongest currency, the US dollar – just to be on the safe side.

China attempts to break this monopoly and is gaining influence. Albeit from a very low level: The yuan’s share of global monetary transactions is only 2.77 percent, while the US dollar’s share is 42 percent. As a reserve currency, the US dollar even amounts to 58 percent, while China’s yuan only accounts for 3 percent.

However, China managed to achieve an important milestone on the way to a stronger yuan: According to calculations by the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, better known as SWIFT, the yuan was used in 49 percent of all China’s cross-border transactions last quarter, including trade. The yuan has thus overtaken the US dollar in this respect for the first time in the history of the People’s Republic. And the yuan is gaining strong momentum. The increase in transactions denominated in yuan is 10 percent compared to last year, while the share of the US dollar has declined by 14 percent.

The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution has warned politicians and authorities about Chinese influence and espionage. According to a security notice published by the authority on Friday, the Chinese government has attempted to expand its international influence in recent years. The International Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (IDCPC) reportedly plays a central role in expanding the global network. The department is part of the Chinese intelligence apparatus. “The aim is to inform the Chinese leadership about the political situation of other states and their military and economic potential,” the notice says.

The IDCPC is thus directly subordinate to the Chinese leadership and supposedly seeks contact with politicians and parties worldwide. The Office for the Protection of the Constitution recommends exercising “particular caution and restraint” when in contact with IDCPC members and also directly addresses German politicians. The IDCPC is “regarded by many German politicians, parties and political organizations as a trustworthy and important cooperation partner,” explains the Office for the Protection of the Constitution.

“The IDCPC members promote understanding of ‘Chinese values’ among parliamentarians of all parties. One of the IDCPC’s common practices is inviting German MPs (current or former) to China to ‘correct’ their image of China in line with the CCP’s agenda,” the note says. Berlin recently unveiled its own China strategy. ari

The United States is providing military aid worth 345 million dollars to Taiwan, the White House announced on Friday. The official announcement did not include a list of weapons systems, but according to media reports, these include air defense systems, reconnaissance drones and ammunition from the US military stockpile. The aim is to accelerate military support for Taiwan and strengthen the democratically governed island in a potential conflict with China.

Taiwan’s defense ministry thanked the US for its “firm security commitment.” A spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington urged the US to “stop creating new factors that could lead to tensions in the Taiwan Strait.” fpe

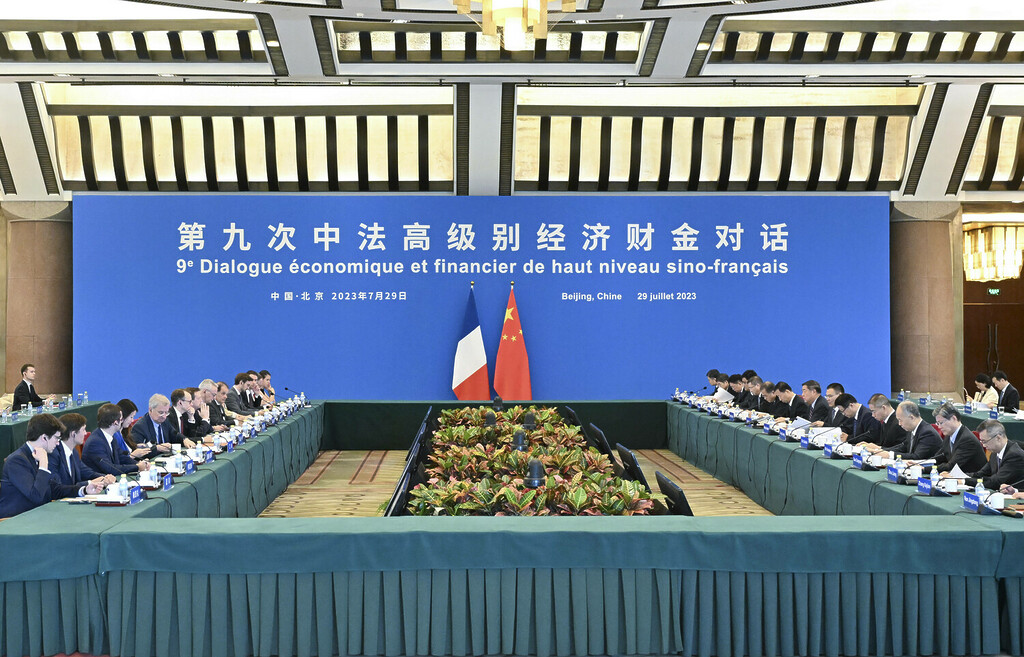

France seeks better access to the Chinese market and a “more balanced” trade relationship – but does not want to decouple from the world’s second-largest economy, French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire stressed in Beijing on Sunday. Le Maire said at a press conference in Beijing that he did not want to encounter legislative or other hurdles to accessing Chinese markets. On Saturday, he met with Vice Premier He Lifeng for “constructive” trade talks, the French minister said.

Le Maire argued against clear decoupling and relativized de-risking: “De-risking does not mean that China is a risk,” Le Maire said. “De-risking means that we want to be more independent and that we don’t want to face any risk in our supply chains if there would be a new crisis, like the COVID one with the total breakdown of some of the value chains.”

At the meeting with He Lifeng, market access is said to have been at the core of the discussions, according to Le Maire. The minister said France was on the right track and paving the way for better access for French cosmetics to the Chinese market. Le Maire said China hoped France could “stabilize” the tone of EU-China relations. Beijing, in turn, was ready to deepen cooperation with Paris in some areas, he said.

China is France’s third-largest trading partner. When asked about the fears of some European car manufacturers that cheap Chinese electric vehicles could flood the European market, Le Maire said France wanted to better bundle French and European EV subsidies to increase competitiveness. He also did not rule out cooperation with China: “We want China to make investments in France in electric vehicles and Europe.” rtr/ari

Chinese human rights lawyer Lu Siwei has been arrested in Laos. Activists and family members now fear that he could be deported to China, where he faces a prison sentence.

As the Associated Press reports, Li Siwei was arrested by Laotian police on Friday morning while boarding a train to Thailand. He was reportedly on his way to Bangkok to catch a flight to the United States, where his wife and daughter live.

Lu was disbarred in China in 2021 after representing pro-democracy activists from Hong Kong. He was subsequently banned from leaving China to pursue a fellowship in the United States. According to an activist working with him, Lu had been carrying valid visas for Laos and the US. fpe

China plans to expand its relations with Georgia. The strategic partnership is supposed to flourish regardless of how the international situation develops, said President Xi Jinping on Friday during a visit of Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili on the sidelines of the Chengdu University Games in southwest China. Georgia is also of interest to China because the country lies on the New Silk Road, with which the People’s Republic aims to establish new trade and energy connections.

However, Georgia’s relationship with China’s close ally Russia has been strained for years. Russia supports separatists in the regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which have broken away from Georgia, and waged war against the neighboring country in 2008. The Georgian government has condemned the Russian war of aggression against Georgia as illegal under international law in the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, but has so far not joined Western sanctions. Shortly after the war broke out, Georgia applied for EU membership. rtr

If you ask Daniel Leese how he came to China, he answers soberly: “It was more of a personal coincidence; in principle, it could have been any other country.” By personal coincidence, he means the Chinese characters that sparked a lasting fascination near the end of his school years and ensured that he ticked the box for sinology when deciding on an academic minor. Leese majored in modern and contemporary history in Marburg, Beijing and Munich. His interest in sinology deepened at Beijing’s prestigious Beida University. He remembers the stimulating intellectual atmosphere, researching sources at flea markets, and conversations with contemporary witnesses that introduced him to taboo areas of Chinese history.

It is precisely these restrictions when dealing with the past that awakened Leese’s ambition at the time. In the years after his first visit to Beijing, he repeatedly spent several months in China, working as a tour guide, exploring the provinces and spending a lot of time in Beijing and Hong Kong. Back then, China was an adventure; it has since become his profession. Since 2012, Leese has been a professor of history and politics of modern China at Freiburg University and has authored numerous books focusing on China, including “Maos langer Schatten: Chinas Umgang mit der Vergangenheit” (Mao’s long shadow: How China deals with its past) which was nominated for the German Nonfiction Book Award in 2021.

“It is an exhausting and challenging task to keep looking behind the curtain of forgetting,” says the sinologist. But he doesn’t shy away from this task because he believes it makes a significant contribution. It is about dealing with historical guilt and how nations can come to terms with injustices they have committed. “This is of key importance – not only for China.”

Leese is currently working on a project about internal communication structures within the Chinese Communist Party and what the party knew about developments at home and abroad in the 1950s and ’60s. However, His latest book, published by C.H. Beck-Verlag, focuses on China’s present. Together with China expert Ming Shi, Leese has selected texts written by leading contemporary Chinese intellectuals, and translated them into German and classified them. With “Chinesisches Denken der Gegenwart – Schlüsseltexte zu Politik und Gesellschaft” (Chinese contemporary thought – key texts on politics and society), the authors want to contribute to a greater understanding of central problems in Chinese politics and society in order to spark a meaningful debate on the country’s development. Svenja Napp

Henrik Muller took over as the new Transformation Manager Operations for Continental in Germany in June. Muller was previously Head Of Production in Qingdao for almost three years.

Charalabos Klados has been Senior Vice President at Colgate-Palmolive and General Counsel Asia Pacific, based in Hong Kong, since July. Klados has been with the US company for more than 15 years.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Do you feel an insatiable hunger for success, money, fame? Or do you yearn for love, romance and affection? Then make sure you don’t fall for a cookie guy or a pastry brat with your rumbling stomach. Because in China, you will not be promised the moon, but rather a flatbread painted in the air, or a pancake, skillfully blotted with a few brushstrokes, and that in the most dazzling colors.

画饼 huàbǐng (“to paint a cookie/pancake” or “to paint a cake/flatbread”) – also in the intensified form 画大饼 huà dàbǐng (“to paint a big cake”) means making empty promises and great, unrealistic hopes to others. This popular expression is derived from the Chinese four-character word (chengyu) 画饼充饥 huàbǐng-chōngjī – “to satisfy one’s hunger with painted cakes,” an old saying for “to fool oneself for comfort.” Because even the ancient Chinese knew: Fictitious cakes do not fill real stomachs.

China’s Internet community has identified two main prototypes among its modern-day fake bakers: The cake-painting boss (画饼老板 huàbǐng lǎobǎn) and the cake-painting man (画饼男 huàbǐngnán) or cake-painting lady (画饼女 huàbǐngnǚ).

The cake-painting boss knows how to dangle carrot cake under the noses of stubborn employees to make them gallop for their best performance. The blinders are always set on the next supposed big promotion / pay rise/bonus payment/profit or share participation. But as it turns out later, it was all just a pie-in-the-sky to squeeze as much performance out of their employees. It may have worked perfectly for the boss as the architect of the cake house, but not for the white-collar baker. No wonder that the Internet community murmurs: 画饼的人永远不会考虑做饼的人 huàbǐng de rén yǒngyuǎn bú huì kǎolǜ zuò bǐng de rén – “those who paint the cake never think about those who bake it.”

The second prototype, the cake-painting guy, follows a similar recipe. House, high income, dream wedding and dream honeymoon – this guy promises his beloved the moon. However, once reality finally sets in, these promises tumble down like a house of cards. China’s women have called the counterpart 画饼男 huàbǐngnán is真心男 zhēnxīnnán – a “man with a real heart,” someone with a genuine interest.

If you are the gullible type, please take another Chinese pastry wisdom to heart: 天上不会掉馅饼 tiānshàng bú huì diào xiànbǐng – “no filled pastry falls from the sky,” or as the English saying goes: There’s no such thing as a free lunch. In other words: nothing is for free. And if, in the unlikely case that luck does strike, the Chinese simply adjust the expression: 天上掉馅饼 tiānshàng diào xiànbǐng “it rains stuffed cookies from the sky” is what they call such scenarios, in other words: “something is handed to you.”

To conclude today’s pastry lesson, here’s a little guide to China’s linguistic bakery: China’s bǐng basics in street food that you should know and have tried include the breakfast classic 烧饼 shāobǐng (Chinese sesame buns, with or without filling), 煎饼 jiānbǐng (hearty Chinese egg crêpe spread with spicy sauce), and 手抓饼 shǒuzhuābǐng (crispy rolled pancake with lettuce and sausage to go – because 手抓 shǒuzhuā means “to grab with your hand”). In the fall, a veritable bǐng boom awaits China visitors every year, namely around the Moon or Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋节 Zhōngqiūjié). Here, 月饼 yuèbǐng “moon cakes” pile up on the shelves with all sorts of fillings, from bean paste to meat wool.

However, China buffs are bound to find a few unexpected “cakes” in various situations in everyday language. For example, “iron cakes” (铁饼 tiěbǐng – meaning discus discs in athletics) and “coal cakes” (煤饼 méibǐng Chinese for coal bricks). Some more edible cakes include persimmon cakes (柿饼 shìbǐng – these are disc-shaped dried persimmon fruits). And passionate tea drinkers sometimes buy a whole “tea cake” (茶饼 chábǐng – tea pressed into slices).

However, there is one Chinese pastry that you will probably only find in Western Chinese restaurants, but not in China itself: The fortune cookie, in Chinese 签语饼 qiānyǔbǐng (literally “oracle saying cookie”). Contrary to popular belief, fortune cookies originated in Japan. In fact, they were completely unknown in China until the 1990s. In their current form, these crunchy cookies “filled” with words of wisdom first appeared on the American West Coast in the early 20th century, introduced by Asian immigrants. Since they are primarily served in Chinese restaurants in the US and Europe as a snack on the way home, many people in the West regard them as the epitome of the Chinese cookie – incorrectly.

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.

De-risking is the name of the game when it comes to relations with the People’s Republic. Germany’s China strategy, which is only a few days old, also mentions minimizing risk as its main goal. But: “There are very different risks – and the concept of risk is not defined in the paper,” says economist and professor of China Business and Economics, Doris Fischer. “Here, the next step would have to be to create clarity first.” Finn Mayer-Kuckuk spoke with Fischer about how this could work, what the worst case for risk minimization would be, and what Germany can do to prepare.

Chinese exports declined in June. Imports also fell significantly. However, these developments should not deceive us, writes Frank Sieren. In international comparison, China’s balance of trade is still in a very good shape. Trade in the Chinese yuan is also gaining momentum.

The German government has presented its China strategy. Is the document suitable as a guideline for economic policy?

I was very skeptical about what kind of document it would be. It turned out much better than I feared, but I would still say that the word strategy does not apply in all respects.

Is it a useful policy paper, nonetheless?

There are clear guidelines in some areas on how the German government wants to act, but the authors had to leave the details open in many areas.

What would the actual implementation by the German government look like?

The central concept of the strategy paper is risk minimization. However, there are very different risks – and the paper does not define the concept of risk. Here, the next step would have to be to first create clarity.

What types of risk do you distinguish?

I see mainly investment risks, supply chain risks and political risks. Normal investment risks exist in all countries where companies are active. In fact, Chinese economic development is currently becoming more risky because the economy is not performing smoothly. There is a lack of demand. This factor also makes companies reconsider and look more at other markets. But whether they needed the discussion about the China strategy for this or not, that is hard to assess.

What about supply chain risks?

A prime example of this was the shipping accident in the Suez Canal, which cut Europe off from Asian goods for several days.

Or the pandemic.

Yes. If the supply chains are finely chiseled and also relatively dependent on one market, then shocks can occur. Then we are suddenly at risk. But that is only partly linked to China. In any case, China is not to blame. Here, every company must and had to clarify for itself: Am I adequately prepared for such irregularities? The industry is already thinking about the supply chain risk. The consensus here is “China plus one.”

This means that each supplied part is not only sourced from one country, but always from another supplier.

It can also be “China plus three.” The regional distribution of risk is a good risk management strategy. Actually, up to now, it should have been said that this is part of a good corporate strategy. However, under the conditions of globalization as we have experienced in the past 20 years, there was a tendency to rely solely on the cheapest suppliers and, moreover, on “just in time” deliveries. Another approach to reducing the risks is increased warehousing. However, companies also do not need a government strategy to understand this.

However, this process has already been underway since the pandemic at the latest, and company representatives assure us that they have the issue at the top of their agenda. Where does the strategy set new impulses?

This is where the third risk comes into play, the potential for using dependencies politically. In the past, we used to say: If trade relations are intensive, that should actually be a guarantee for peaceful relations. But now we have learned that trade dependency can also be used strategically to achieve foreign policy goals through economic pressure.

Here, politicians are now openly discussing the risk of an invasion of Taiwan with catastrophic repercussions on trade relations.

That would be the worst case.

What can Germany do to prepare?

We must be clear to what extent we can minimize these risks at all. There are also scenarios in which China abuses its market power to exert pressure against a single country. The incident with Lithuania, when China froze trade with the country, was a wake-up call in this respect. Before that, the problems that other countries like Australia had with China were not really taken seriously. Now there is a greater awareness of these risks. In addition, the US is constantly intensifying its conflict with China.

If we look again at the big picture and the government’s wish to eliminate these risks as far as possible. How can that be achieved?

That is almost impossible. Even if we only trade with closely allied countries, they, in turn, have their own China risks. Germany and the EU cannot become self-sufficient either without giving up a great deal of wealth. We have to bear these risks to some extent. De-risking in the sense of reducing risks is sensible, but we will not be able to eliminate the risks. As an exporting country, we are a risk society and will continue to be one.

Are politicians perhaps even creating new risks in the pursuit of security?

The more we pursue anti-China policies, the more we push the Chinese government into this corner. And that’s why I’m very wary of always painting the worst-case scenario on the wall.

However, companies would then also have to prepare for this eventuality.

We cannot expect companies to prepare in detail for a possible war between China and Taiwan in three, five or ten years, or not at all. They would have to prepare for entirely different scenarios, for example, in the Middle East, Africa – or the United States.

Do companies read the China strategy?

In practice, entrepreneurs and executives probably have other concerns. Many industries are currently mainly concerned with whether their products are competitive. One company representative told me that they had looked at it, but it is not really important to them.

So not much will change in the short term?

We are in an economy-political loop in which we are and remain dependent on goods from China, and China is in a loop in which it remains dependent on exports. Despite assurances to the contrary, we cannot easily break free.

How is this strategy being received in China?

Actually, you can explain a risk strategy to the Chinese quite well. For 20 years, China has done nothing but deal with the risks for the Chinese economy and society, with the conventional risks, but above all, with the non-conventional risks. It was also positively registered in Beijing that it did not turn out to be a pure anti-China strategy.

Doris Fischer is a professor of China Business and Economics at the Julius-Maximilians-University of Wuerzburg. She has a Sinology and Business Administration background and holds a Ph.D. in Economics. Her areas of research include China’s economic and industrial policy. She is currently also the Vice President for Internationalization and Alumni at the University of Wuerzburg.

Chinese exports contracted by more than 12 percent year-on-year in June, the biggest decline since February 2020. Imports also fell significantly. This is mainly due to the fact that major trading partners such as the US, EU and Japan are buying less from China. Exports fell by 12.4 percent year-on-year to around 285 billion US dollars. The imports of the second-largest economy fell by 6.8 percent to 215 billion dollars. Foreign trade had already slowed down in the previous months. That sounds alarming.

But Beijing also has reason to celebrate: For the first time in its history, China’s trade volume exceeded the 20 trillion yuan mark during the first half of this year. That is the equivalent of 2.8 trillion US dollars. In this period, despite the weakening domestic economy and low international demand, the trade volume has increased by 400 billion yuan (about 50 billion euros), which is roughly equivalent to the value of all the roughly three million Chinese cars exported in 2022.

How China is actually performing internationally despite a year-on-year trade decline is revealed when comparing China’s trade balance with that of other countries.

The figures for the first half of the year are not yet available everywhere. But the direction is clear. Although China’s trade is not developing as expected, the country still generated a trade surplus of well over 60 billion US dollars during the first six months of 2023. In June, it was even over 70 billion US dollars. This means China is doing very well in international comparison.

The USA, China’s largest competitor, is again running a high trade deficit this year. In the first half of the year, it is already at around 70 billion US dollars per month. Japan’s monthly deficit is the equivalent of about 50 billion US dollars, India’s is around 17 billion US dollars. The EU’s trade balance at least breaks even. This means that the EU does not earn any money, but does not make any trade losses either.

And the Germans at least generate a surplus of around 15 billion US dollars. A comparison with the figures from 2022 shows that there is no trend reversal in sight: China had a record surplus of just under 877 billion US dollars. A growth of twelve percent. The US had a record deficit of 945 billion US dollars. The EU came in at minus 432 billion. Japan had a deficit of 150 billion US dollars. In India, it was minus 122 billion US dollars. And Germany had a surplus of just under 80 billion euros in 2022. The only exception in the first half of the year was the EU, which at least had a neutral trade balance.

What does this mean for international competition? Like with a business or a household, it is always better to earn more than you spend. The only two countries mentioned where this is the case are China and Germany. For other countries, in order to pay the deficit, a country usually needs foreign loans. And that is why foreign debt correlates with deficits. This is why China has the lowest external debt. These are measured as a percentage of GDP.

The leader is Germany with 156 percent, followed by the EU with 117 percent. The USA and Japan are at around 100 percent. India at 20 percent. China comes out best, with an external debt-to-GDP ratio of 13 percent. At the same time, China, together with Japan, is the largest creditor of the United States. Overall, it can be said that the more a country makes from trade and the less external debt it has, the more independent it is both economically and politically.

Because debt hides a currency risk: Everything that a country has to buy on the global market has to be paid for in a foreign currency. External debt in return is also denominated in a foreign currency, mostly US dollars. Even in leading exporting nations, most of the GDP is generated in the respective national currency. In China, that is 62 percent. In Germany, it is a good 50 percent.

If a country experiences an economic crisis, many international investors sell the respective currency which causes the exchange rate to fall. The crisis country now receives fewer US dollars for its own currency. This increases the US dollar debt. The indebted country then generally starts to print money. As a result, prices go up and the inflationary spiral begins. The currency becomes weaker and weaker, the debts grow heavier and heavier. Countries are at the mercy of international pressure. The last time this happened on a large scale in Asia was in 1997 during the Asian crisis.

So the impression is: Regarding such a development, China, with its low debt, is in the best position and the USA is in the worst position. However, this is not entirely true. For there is a big difference between China and the United States: The US dollar is so strong that it cannot be put under pressure by any other currency, no matter how heavy the burden of debt may be. On the contrary: In times of global crisis, the US dollar grows stronger because many exchange their money for the strongest currency, the US dollar – just to be on the safe side.

China attempts to break this monopoly and is gaining influence. Albeit from a very low level: The yuan’s share of global monetary transactions is only 2.77 percent, while the US dollar’s share is 42 percent. As a reserve currency, the US dollar even amounts to 58 percent, while China’s yuan only accounts for 3 percent.

However, China managed to achieve an important milestone on the way to a stronger yuan: According to calculations by the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, better known as SWIFT, the yuan was used in 49 percent of all China’s cross-border transactions last quarter, including trade. The yuan has thus overtaken the US dollar in this respect for the first time in the history of the People’s Republic. And the yuan is gaining strong momentum. The increase in transactions denominated in yuan is 10 percent compared to last year, while the share of the US dollar has declined by 14 percent.

The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution has warned politicians and authorities about Chinese influence and espionage. According to a security notice published by the authority on Friday, the Chinese government has attempted to expand its international influence in recent years. The International Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (IDCPC) reportedly plays a central role in expanding the global network. The department is part of the Chinese intelligence apparatus. “The aim is to inform the Chinese leadership about the political situation of other states and their military and economic potential,” the notice says.

The IDCPC is thus directly subordinate to the Chinese leadership and supposedly seeks contact with politicians and parties worldwide. The Office for the Protection of the Constitution recommends exercising “particular caution and restraint” when in contact with IDCPC members and also directly addresses German politicians. The IDCPC is “regarded by many German politicians, parties and political organizations as a trustworthy and important cooperation partner,” explains the Office for the Protection of the Constitution.

“The IDCPC members promote understanding of ‘Chinese values’ among parliamentarians of all parties. One of the IDCPC’s common practices is inviting German MPs (current or former) to China to ‘correct’ their image of China in line with the CCP’s agenda,” the note says. Berlin recently unveiled its own China strategy. ari

The United States is providing military aid worth 345 million dollars to Taiwan, the White House announced on Friday. The official announcement did not include a list of weapons systems, but according to media reports, these include air defense systems, reconnaissance drones and ammunition from the US military stockpile. The aim is to accelerate military support for Taiwan and strengthen the democratically governed island in a potential conflict with China.

Taiwan’s defense ministry thanked the US for its “firm security commitment.” A spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington urged the US to “stop creating new factors that could lead to tensions in the Taiwan Strait.” fpe

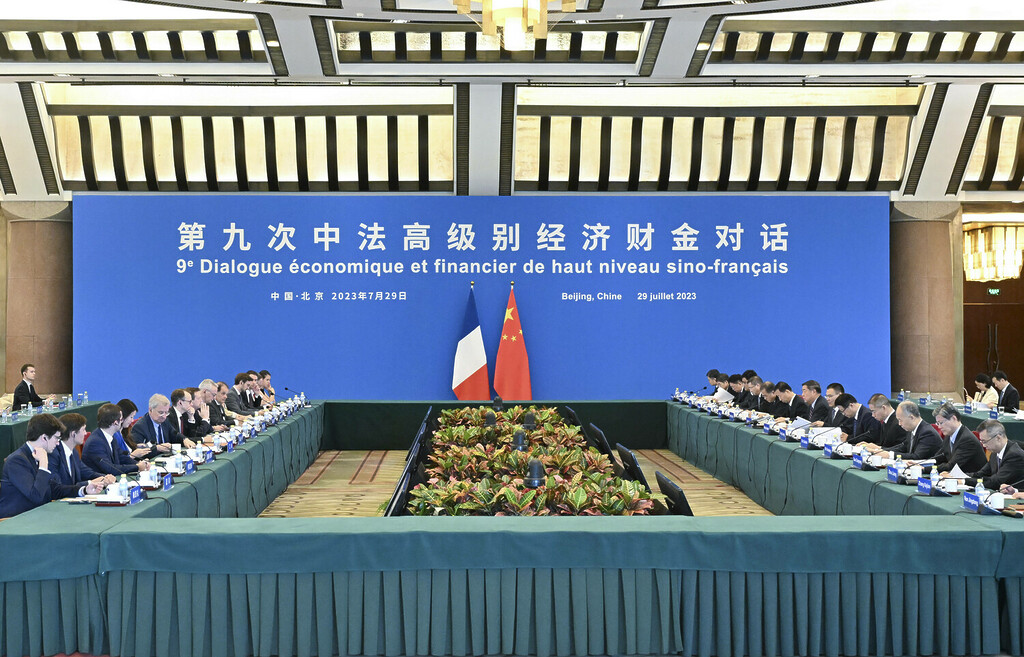

France seeks better access to the Chinese market and a “more balanced” trade relationship – but does not want to decouple from the world’s second-largest economy, French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire stressed in Beijing on Sunday. Le Maire said at a press conference in Beijing that he did not want to encounter legislative or other hurdles to accessing Chinese markets. On Saturday, he met with Vice Premier He Lifeng for “constructive” trade talks, the French minister said.

Le Maire argued against clear decoupling and relativized de-risking: “De-risking does not mean that China is a risk,” Le Maire said. “De-risking means that we want to be more independent and that we don’t want to face any risk in our supply chains if there would be a new crisis, like the COVID one with the total breakdown of some of the value chains.”

At the meeting with He Lifeng, market access is said to have been at the core of the discussions, according to Le Maire. The minister said France was on the right track and paving the way for better access for French cosmetics to the Chinese market. Le Maire said China hoped France could “stabilize” the tone of EU-China relations. Beijing, in turn, was ready to deepen cooperation with Paris in some areas, he said.

China is France’s third-largest trading partner. When asked about the fears of some European car manufacturers that cheap Chinese electric vehicles could flood the European market, Le Maire said France wanted to better bundle French and European EV subsidies to increase competitiveness. He also did not rule out cooperation with China: “We want China to make investments in France in electric vehicles and Europe.” rtr/ari

Chinese human rights lawyer Lu Siwei has been arrested in Laos. Activists and family members now fear that he could be deported to China, where he faces a prison sentence.

As the Associated Press reports, Li Siwei was arrested by Laotian police on Friday morning while boarding a train to Thailand. He was reportedly on his way to Bangkok to catch a flight to the United States, where his wife and daughter live.

Lu was disbarred in China in 2021 after representing pro-democracy activists from Hong Kong. He was subsequently banned from leaving China to pursue a fellowship in the United States. According to an activist working with him, Lu had been carrying valid visas for Laos and the US. fpe

China plans to expand its relations with Georgia. The strategic partnership is supposed to flourish regardless of how the international situation develops, said President Xi Jinping on Friday during a visit of Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili on the sidelines of the Chengdu University Games in southwest China. Georgia is also of interest to China because the country lies on the New Silk Road, with which the People’s Republic aims to establish new trade and energy connections.

However, Georgia’s relationship with China’s close ally Russia has been strained for years. Russia supports separatists in the regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which have broken away from Georgia, and waged war against the neighboring country in 2008. The Georgian government has condemned the Russian war of aggression against Georgia as illegal under international law in the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, but has so far not joined Western sanctions. Shortly after the war broke out, Georgia applied for EU membership. rtr

If you ask Daniel Leese how he came to China, he answers soberly: “It was more of a personal coincidence; in principle, it could have been any other country.” By personal coincidence, he means the Chinese characters that sparked a lasting fascination near the end of his school years and ensured that he ticked the box for sinology when deciding on an academic minor. Leese majored in modern and contemporary history in Marburg, Beijing and Munich. His interest in sinology deepened at Beijing’s prestigious Beida University. He remembers the stimulating intellectual atmosphere, researching sources at flea markets, and conversations with contemporary witnesses that introduced him to taboo areas of Chinese history.

It is precisely these restrictions when dealing with the past that awakened Leese’s ambition at the time. In the years after his first visit to Beijing, he repeatedly spent several months in China, working as a tour guide, exploring the provinces and spending a lot of time in Beijing and Hong Kong. Back then, China was an adventure; it has since become his profession. Since 2012, Leese has been a professor of history and politics of modern China at Freiburg University and has authored numerous books focusing on China, including “Maos langer Schatten: Chinas Umgang mit der Vergangenheit” (Mao’s long shadow: How China deals with its past) which was nominated for the German Nonfiction Book Award in 2021.

“It is an exhausting and challenging task to keep looking behind the curtain of forgetting,” says the sinologist. But he doesn’t shy away from this task because he believes it makes a significant contribution. It is about dealing with historical guilt and how nations can come to terms with injustices they have committed. “This is of key importance – not only for China.”

Leese is currently working on a project about internal communication structures within the Chinese Communist Party and what the party knew about developments at home and abroad in the 1950s and ’60s. However, His latest book, published by C.H. Beck-Verlag, focuses on China’s present. Together with China expert Ming Shi, Leese has selected texts written by leading contemporary Chinese intellectuals, and translated them into German and classified them. With “Chinesisches Denken der Gegenwart – Schlüsseltexte zu Politik und Gesellschaft” (Chinese contemporary thought – key texts on politics and society), the authors want to contribute to a greater understanding of central problems in Chinese politics and society in order to spark a meaningful debate on the country’s development. Svenja Napp

Henrik Muller took over as the new Transformation Manager Operations for Continental in Germany in June. Muller was previously Head Of Production in Qingdao for almost three years.

Charalabos Klados has been Senior Vice President at Colgate-Palmolive and General Counsel Asia Pacific, based in Hong Kong, since July. Klados has been with the US company for more than 15 years.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Do you feel an insatiable hunger for success, money, fame? Or do you yearn for love, romance and affection? Then make sure you don’t fall for a cookie guy or a pastry brat with your rumbling stomach. Because in China, you will not be promised the moon, but rather a flatbread painted in the air, or a pancake, skillfully blotted with a few brushstrokes, and that in the most dazzling colors.

画饼 huàbǐng (“to paint a cookie/pancake” or “to paint a cake/flatbread”) – also in the intensified form 画大饼 huà dàbǐng (“to paint a big cake”) means making empty promises and great, unrealistic hopes to others. This popular expression is derived from the Chinese four-character word (chengyu) 画饼充饥 huàbǐng-chōngjī – “to satisfy one’s hunger with painted cakes,” an old saying for “to fool oneself for comfort.” Because even the ancient Chinese knew: Fictitious cakes do not fill real stomachs.

China’s Internet community has identified two main prototypes among its modern-day fake bakers: The cake-painting boss (画饼老板 huàbǐng lǎobǎn) and the cake-painting man (画饼男 huàbǐngnán) or cake-painting lady (画饼女 huàbǐngnǚ).

The cake-painting boss knows how to dangle carrot cake under the noses of stubborn employees to make them gallop for their best performance. The blinders are always set on the next supposed big promotion / pay rise/bonus payment/profit or share participation. But as it turns out later, it was all just a pie-in-the-sky to squeeze as much performance out of their employees. It may have worked perfectly for the boss as the architect of the cake house, but not for the white-collar baker. No wonder that the Internet community murmurs: 画饼的人永远不会考虑做饼的人 huàbǐng de rén yǒngyuǎn bú huì kǎolǜ zuò bǐng de rén – “those who paint the cake never think about those who bake it.”

The second prototype, the cake-painting guy, follows a similar recipe. House, high income, dream wedding and dream honeymoon – this guy promises his beloved the moon. However, once reality finally sets in, these promises tumble down like a house of cards. China’s women have called the counterpart 画饼男 huàbǐngnán is真心男 zhēnxīnnán – a “man with a real heart,” someone with a genuine interest.

If you are the gullible type, please take another Chinese pastry wisdom to heart: 天上不会掉馅饼 tiānshàng bú huì diào xiànbǐng – “no filled pastry falls from the sky,” or as the English saying goes: There’s no such thing as a free lunch. In other words: nothing is for free. And if, in the unlikely case that luck does strike, the Chinese simply adjust the expression: 天上掉馅饼 tiānshàng diào xiànbǐng “it rains stuffed cookies from the sky” is what they call such scenarios, in other words: “something is handed to you.”

To conclude today’s pastry lesson, here’s a little guide to China’s linguistic bakery: China’s bǐng basics in street food that you should know and have tried include the breakfast classic 烧饼 shāobǐng (Chinese sesame buns, with or without filling), 煎饼 jiānbǐng (hearty Chinese egg crêpe spread with spicy sauce), and 手抓饼 shǒuzhuābǐng (crispy rolled pancake with lettuce and sausage to go – because 手抓 shǒuzhuā means “to grab with your hand”). In the fall, a veritable bǐng boom awaits China visitors every year, namely around the Moon or Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋节 Zhōngqiūjié). Here, 月饼 yuèbǐng “moon cakes” pile up on the shelves with all sorts of fillings, from bean paste to meat wool.

However, China buffs are bound to find a few unexpected “cakes” in various situations in everyday language. For example, “iron cakes” (铁饼 tiěbǐng – meaning discus discs in athletics) and “coal cakes” (煤饼 méibǐng Chinese for coal bricks). Some more edible cakes include persimmon cakes (柿饼 shìbǐng – these are disc-shaped dried persimmon fruits). And passionate tea drinkers sometimes buy a whole “tea cake” (茶饼 chábǐng – tea pressed into slices).

However, there is one Chinese pastry that you will probably only find in Western Chinese restaurants, but not in China itself: The fortune cookie, in Chinese 签语饼 qiānyǔbǐng (literally “oracle saying cookie”). Contrary to popular belief, fortune cookies originated in Japan. In fact, they were completely unknown in China until the 1990s. In their current form, these crunchy cookies “filled” with words of wisdom first appeared on the American West Coast in the early 20th century, introduced by Asian immigrants. Since they are primarily served in Chinese restaurants in the US and Europe as a snack on the way home, many people in the West regard them as the epitome of the Chinese cookie – incorrectly.

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.