Ursula von der Leyen has set the course as President, now, the Commission must deliver and flesh out de-risking. Amelie Richter reports from Strasbourg on a series of initiatives. Officials have presented a list of technologies that Europe wishes to protect in particular. Incidentally, they are suspiciously similar to the lists of key technologies that China also works with – and which it has long since shielded from foreign access.

China’s secrecy sometimes drives us journalists crazy. Sometimes, a statistic that should be on a ministry’s website is nowhere to be found. I suspect scientists and think tankers feel the same way. But this is not sloppiness, there is a method to it, as Christiane Kuehl describes today using the energy sector as an example. Figures on electricity production are to be kept secret, is an instruction from the very top. And anyone who wants to look into them nevertheless makes himself a suspect of espionage. Transparency looks different.

The EU Commission has drafted a list of critical technologies the European Union wants to protect from rivals. Digital Commissioner Věra Jourová and EU Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton presented the list in Strasbourg on Tuesday. The list contains a total of ten technologies. However, four of them are designated as particularly dangerous should they fall into the wrong hands:

In addition to these four areas, the list also includes issues such as cybersecurity, sensors, energy, nuclear and fusion technology, robotics and also materials such as nano and smart materials. “Europe is adapting to the new geopolitical realities, putting an end to the era of naivety and acting as a real geopolitical power,” said Commissioner Breton at the presentation.

The list, like the list on critical raw materials, is an element of the economic security strategy first presented by the EU Commission in June. This is the first time Brussels has given its economic policy a security aspect – a fundamental change for the EU, previously based on the concept of free trade.

The EU Commission considers three criteria decisive for the selection of the technologies on these lists. Firstly, the “transformative character” of the technology. By this, the EU Commission means the potential for “radical changes for sectors” by the technology. The second criterion is the risk of dual use, i.e., for civilian and military purposes. The third characteristic is the potential for human rights violations.

However, the question remains about how exactly these technologies will be protected. The EU Commission has not yet specified whether its aim is, for example, to prevent access from third countries to European technology or to better screen European investments in these areas abroad through outbound investment screening. A cross-section has now been found with the list, said Breton. Now, however, he added that it is necessary to take a closer look to fight dependencies.

To this end, a joint risk assessment will be conducted with the 27 member states. “To be a player, we need a united EU position, based on a common assessment of the risks,” said EU Commissioner Jourová.

The lack of a common position became visible, for example, when the Netherlands independently agreed with the US earlier this year to ban the export of advanced chip manufacturing equipment to China. There was subsequent criticism from Brussels and other European capitals that this should have been an EU-wide decision.

While the EU Commission presented its plans, the EU Parliament on Tuesday put its money where its mouth is on another matter: MEPs waved through the Anti Coercion Tool (ACI) with a large majority of votes. “Today we deliver. We’ve filled our toolbox with one additional defensive instrument,” wrote SPD European politician Bernd Lange on X, formerly Twitter. According to Lange, who chairs the parliament’s trade committee, the ACI will come into force in a few weeks.

The background to the new trade instrument was, among other things, Chinese trade restrictions against Lithuania after the government in Vilnius allowed the opening of a “Taiwan office” in Taipei. In such cases, the EU will be able to restrict access to public tenders for companies from the respective countries or block the sale of certain products from Europe. Such steps, however, are meant to be a last resort, when other options, especially diplomatic ones, have been exhausted.

EU Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis welcomed the strong support for the new trade tool. On Tuesday, he answered questions from EU parliamentarians on China trade policy and his recent trip to the People’s Republic. On the latter and the trade dialogue that took place there, Dombrovskis said that there had been no breakthrough, but meaningful steps.

Is China now expanding its anti-espionage campaign to the energy sector? Or is it just an overzealous head of a key government agency? That is what observers wondered after Zhang Jianhua, Director of the National Energy Administration, urged companies in the sector in August to avoid “leaks” in “sensitive areas” of the energy sector, like the nuclear and oil industries. What is certain, however, is that information on China’s energy supply will be harder to obtain than ever before.

Zhang wrote that “hostile foreign forces” were gathering data and information to “distort and defame” China’s energy transition. It remained unclear precisely what he meant by this – but he emphasized the growing risks that he believes emanate from smartphones, social media and hacker attacks. The report, which was unusually harsh for an agency head, was made in the context of China’s broader anti-espionage laws, Bloomberg reported.

Zhang did not mention any names in his text, but seemed to be referring to companies that gather market information, as well as traditional intelligence agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) dealing with energy and climate. He called for more inspections and stricter penalties for violations. Experts reacted to the text with concern. “This does not bode well for data availability, research, media or civil society,” wrote Lauri Myllyvirta, a China expert at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air on X, formerly Twitter.

But only a few days later, Zhang’s post disappeared from the net, as did most of the reports on it in the state media. It was only visible on a few websites, Myllyvirta reported, after he had scoured the net: “As always the deletion is even more interesting than the speech itself.”

China is the world’s largest energy producer and consumer, extracting and burning more than half the world’s coal, importing more oil and gas than any other country – and building the world’s largest solar and wind power plants. China senses espionage in all these areas, if Zhang Jianhua can be taken at his word. Meanwhile, the already limited transparency in China continues to decline, not least because of the country’s economic woes. For example, the National Bureau of Statistics simply no longer releases undesirable data, such as growing youth unemployment.

Since Xi took office in 2012, tens of thousands of the more than 80,000 statistics published each year have been deleted, according to research by the Financial Times. This also includes the environment: “Water data already difficult to get, and if I had to guess, agri data will be next,” says Shanghai environmental consultant Richard Brubaker. But what options does someone who requires these numbers have? Due diligence, market research? However, such in-depth research activities can already be considered illegal under the anti-espionage law.

In any case, in the deleted post, Zhang Jianhua from the energy authority demanded: “We must actively cultivate a culture of confidentiality, keeping secrets and being cautious.” China’s state-owned companies, in particular, don’t need to be told twice. In July, the oil company CNOOC already stated that it held a meeting with fuel traders to increase the confidentiality standards of their work.

For instance, the increasing oil imports from Russia are a matter of secrecy. Chinese customs data showed that China imported 60.66 million tonnes of crude oil from Russia in the first seven months of this year, an increase of roughly 25 percent over the same period last year. But it is unclear who exactly in China is importing this oil.

Most likely, it is the country’s three big state-owned oil companies: China National Petroleum (CNPC), China Petroleum & Chemical (Sinopec) and China National Offshore Oil (CNOOC). But at their recent financial press conferences in Hong Kong, executives from their listed core companies were all very reluctant to give details about their Russian business, according to Nikkei Asia.

So anyone wanting to learn more about China’s oil imports from Russia checks ship trackers or tries to get information in confidential conversations. This is how Bloomberg traced the route of an unregistered oil shipment from Russia’s Ust-Luga in the Baltic Sea to Dongjiakou in China. Such investigations, however, could be considered espionage under Chinese interpretation.

Even information about the energy transition is not as easily obtainable in China as in the USA and Europe. Even though Bloomberg states that government agencies and research companies at least regularly report data that companies, investors and scientists can use as a basis to derive trends for global trade flows and China’s climate efforts.

China owns many patents in the highly subsidized renewable sector, produces solar plants and wind turbines, and is researching electricity storage systems, which are crucial for the energy transition. According to the Japanese newspaper Nikkei Asia, China is currently developing into a hub for research into new types of perovskite solar cells. But access to information is not always so easy, depending on the actor and the location. The operators of large-scale projects such as offshore wind farms or energy storage systems are usually state-owned companies that tend to keep details to a minimum.

The state-owned company Sinopec, for example, started what it claims is the world’s largest plant for the production of green hydrogen in Xinjiang in July. Sinopec announced that its Xinjiang Kuqa Green Hydrogen Pilot Project uses its own photovoltaic plants the size of 900 football fields to produce 20,000 tons of green hydrogen per year from solar energy through water electrolysis. The hydrogen produced will initially be used for oil refining in a nearby chemical plant owned by the company. That’s something, at least.

The Singapore-based specialist website Upstream also reports that the plant features 52 electrolyzers, 13 of which were supplied by a joint venture with Belgian participation. Access to Xinjiang is almost impossible for international market research companies. So, according to Zhang’s interpretation, would it be espionage if a foreigner tried to find out details about the project and its cooperation partners via the Belgian participants?

“Still too early to tell the exact impacts but almost certain that having honest, sincere, and off-script exchanges with CN counterparts would become even more difficult,” Liu Hongqiao, an expert on China’s climate policy, wrote on X after Zhang’s article surfaced. He said it seemed to be not only about data but also about narratives.

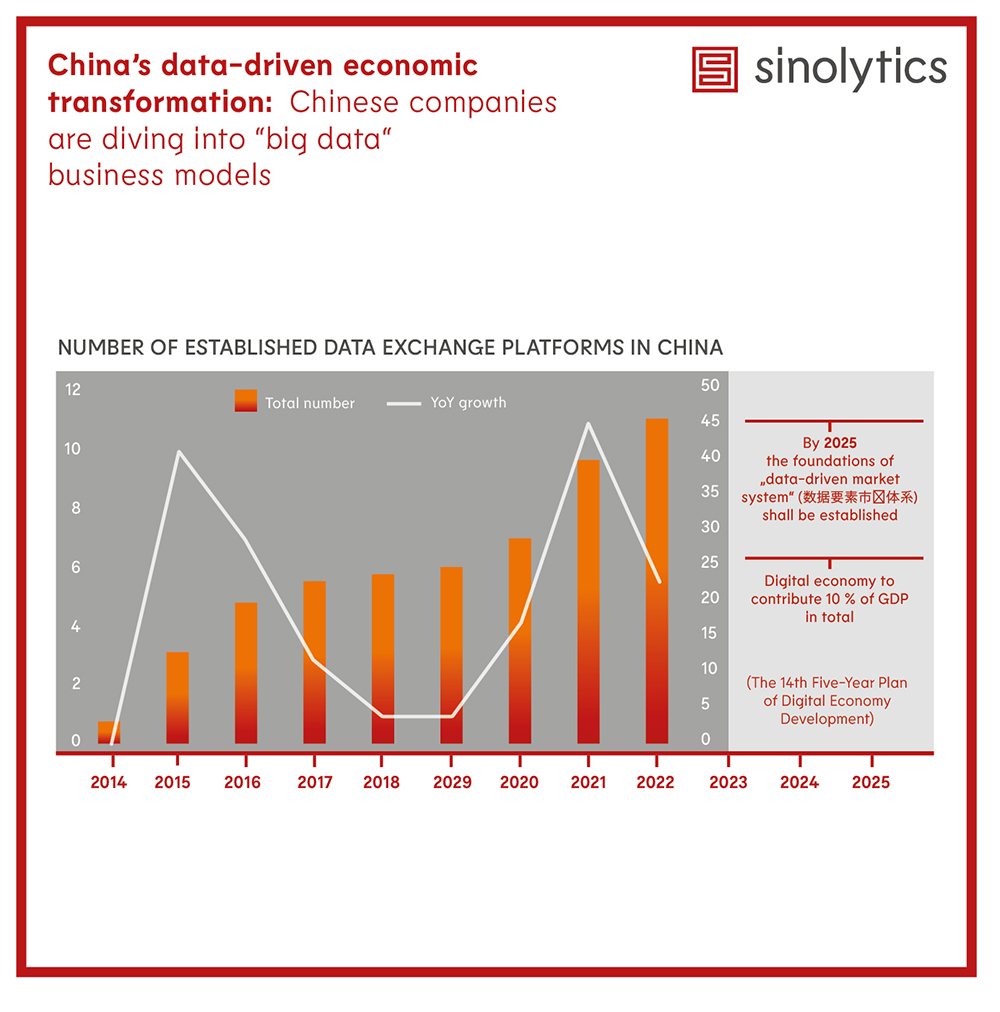

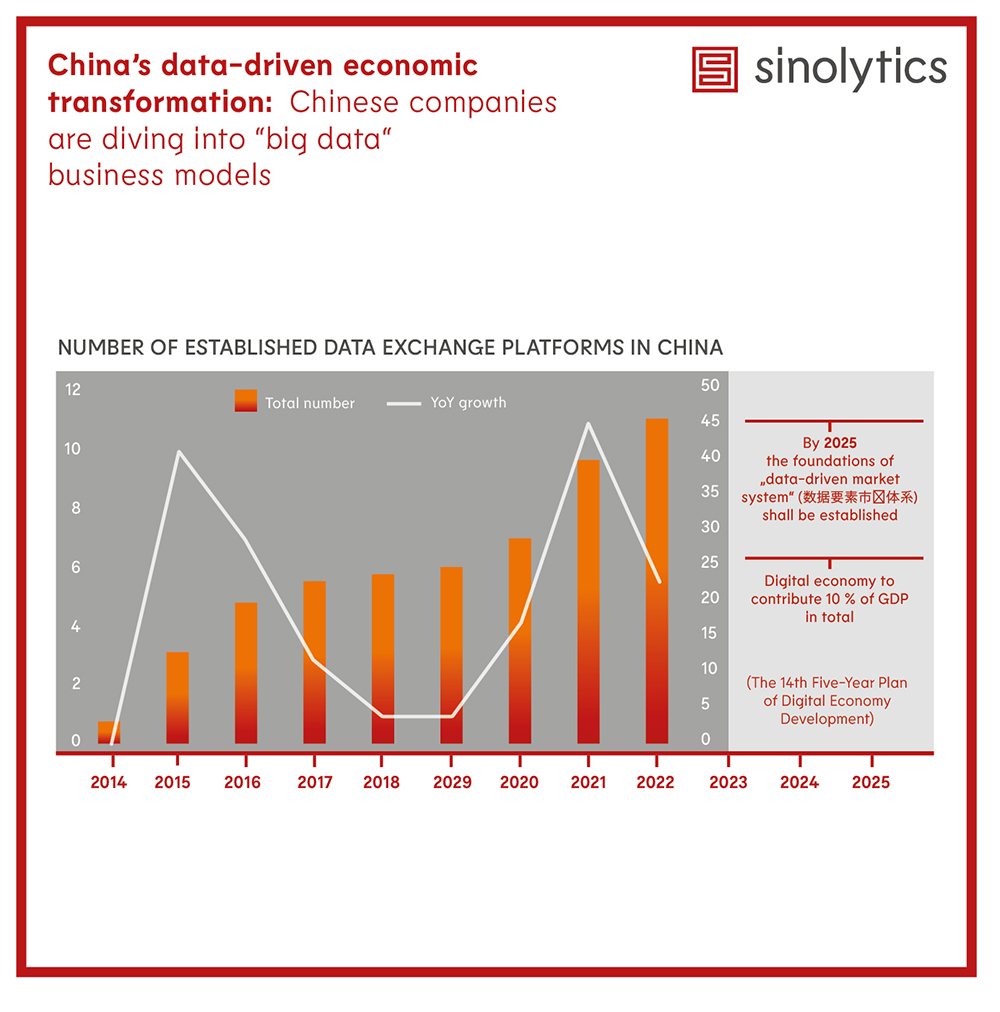

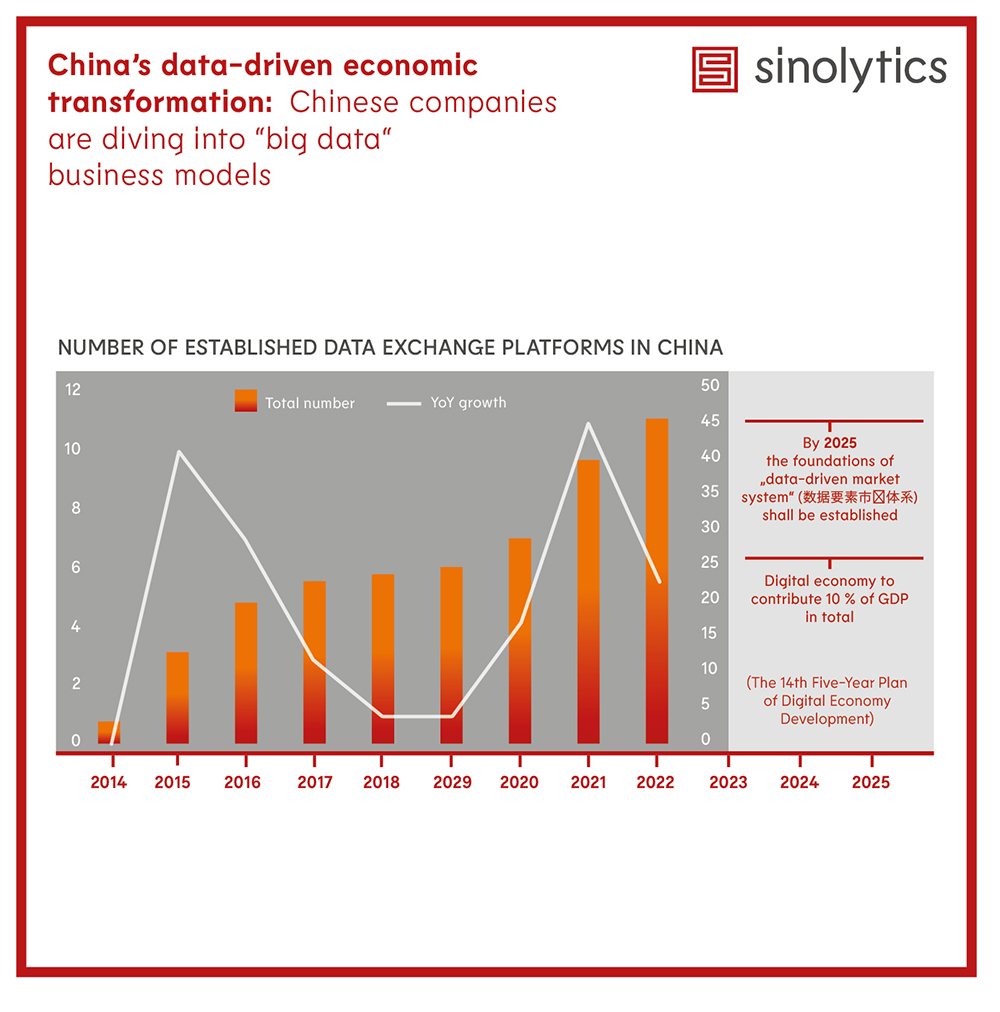

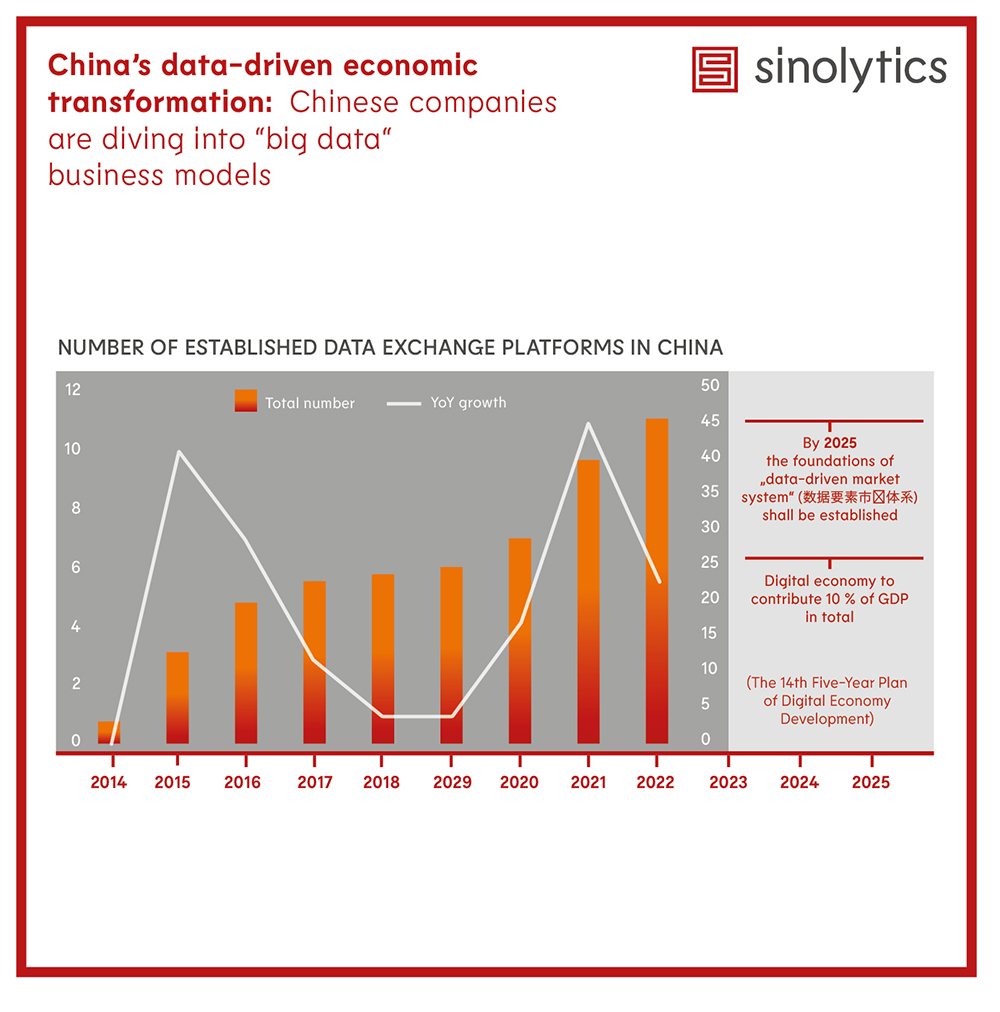

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

China is opening its market to pork meat from Russian regions that are free of African swine fever (ASF). This is reported by the news service Agra-Europe. The 15-year import ban by the Chinese customs administration has been lifted. The ban has existed since 2008 after the African swine fever virus ran rampant in Russia. That is why only imports from regions of Russia that are proven to be free of ASF are allowed.

So far, Germany has been trying unsuccessfully to convince China to implement such a solution. And this is even though the People’s Republic is exporting more and more meat. Between January and August 2023, around 1.17 million tons of pork have been imported, almost ten percent more than in the same period last year, according to the Ministry of Agriculture in Beijing. In addition, pork offal imports increased by nearly eight percent to 780,000 tons.

However, these volumes do not come close to the record figures of 2020 and 2021. The biggest suppliers of meat so far this year have been Spain and Brazil, and of by-products the USA and Spain. Henrike Schirmacher

After a three-day break, the shares of the ailing real estate group Evergrande returned to trading on the Hong Kong stock exchange on Tuesday. The share price increased at a low level by as much as 28 percent during the trading day. However, they still only closed at a price of 41 Hong Kong cents, well below the level before China’s real estate crisis.

Evergrande has no prospect of financial recovery in the medium term. Therefore, the share price increase is likely due to short-term speculation with penny stocks. There is no basis for confidence in the company.

The reason for the trading pause was the launch of an investigation in which company CEO Xu Jiayin (Cantonese: Hui Ka-yan) is supposed to participate. He was detained last week. Details were not available. fin

The US technology company Apple is giving in to pressure from China and restricting access to applications in its app store in the People’s Republic. This is reported by the South China Morning Post. In recent days, the American company had still attempted to avert stricter app censorship.

Previously, iPhone owners in China could download and install Western apps via VPN. However, this represented at least a legal gray area, if not a regulatory gap, when it came to banned apps. In the future, only apps licensed by the Ministry of Information MIIT will be listed in the app store. Communication apps such as WhatsApp, X (formerly Twitter), or YouTube could be particularly affected. This will make it more difficult for iPhone users who set up their smartphones in China for the first time to install these apps. fin

Rahile Dawut’s life sentence is symbolic of the plight of Uyghurs in China’s province of Xinjiang. The latest results of Xinjiang investigations show that the number of Uyghur short-term camp detainees has drastically decreased recently. However, in the same period, extremely long prison sentences have increased steeply. However, what may seem like a positive development to outsiders is no reason for hope for the local population. And so, anthropologist Dawut must also assume that she will never live in freedom again.

Despite the odds, Dawut still hoped until recently that her sentence could be overturned. In 2018, a court deemed her a “danger to national security” and found her guilty of “splittism.” Because Dawut’s case, like thousands and thousands of others in the region, was tried behind closed doors, the nature of her offense is unclear.

Recent investigations have revealed that out of a seven-figure number of people sent to the internment and re-education camps by the Chinese government anywhere from a few months to a few years, only a few tens of thousands remain.

However, this does not mean normalization, as the Danish Xinjiang researcher Rune Steenberg claims. The years of mass intimidation are now followed by the systematic disintegration of Uyghur society – in a most perfidious way.

The intellectual elite and several hundred thousand other Uyghurs have been moved to regular prisons and have virtually no prospect of returning to life soon. This emerges from Steenberg’s research. The rest of the population is not only deeply intimidated by the experiences of the past years. They behave as inconspicuously as possible to avoid harsh punishments against themselves and family members.

In addition, they are closely monitored at their workplaces through increasing integration into local industry. The sophisticated technical means of facial recognition, location tracking and communications monitoring have largely replaced internment camps as control instances.

“Rahile Dawut is a secular scholar who is known to have obeyed the laws and regulations of the Chinese government,” says researcher Steenberg about the 57-year-old. He is convinced that neither she nor thousands of other Xinjiang intellectuals can be accused of any ties to terror and extremism.

Dawut’s work as an anthropologist is known far beyond China’s borders. She was an expert on the tradition and culture of the Uyghur ethnic group and taught at Xinjiang University in the regional capital, Urumqi. In 2007, she founded a local research institute on minority customs in China. She gave seminars at renowned universities in the United States and the United Kingdom. In 2020, the academic network Scholars at Risk honored her with the Courage to Think Award. She was also a member of the Communist Party for 30 years.

Her case prompted the US State Department to condemn her detention as unjustified in a statement last week. It is unclear where Dawut is being held, how she is doing, or if she might have had contact with family members in Xinjiang since her arrest in 2017.

At the very least, it became certain a few days ago that she was still alive. But the hope for a reduced sentence is dead. The US human rights foundation Dui Hua has received confirmation from a source in the Chinese government that Dawut’s appeal has been rejected and that her life sentence is now final. grz

Ashwani Muppasani will be the new COO for India and Asia Pacific at car company Stellantis. Muppasani previously headed the National Sales Company for Stellantis in China.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

A flagship store for small plastic figurines? Absolutely. Chinese toy manufacturer Pop Mart International has opened its first flagship store in Thailand’s Central World shopping mall. Pop Mart is one of the largest toy manufacturers in China.

Ursula von der Leyen has set the course as President, now, the Commission must deliver and flesh out de-risking. Amelie Richter reports from Strasbourg on a series of initiatives. Officials have presented a list of technologies that Europe wishes to protect in particular. Incidentally, they are suspiciously similar to the lists of key technologies that China also works with – and which it has long since shielded from foreign access.

China’s secrecy sometimes drives us journalists crazy. Sometimes, a statistic that should be on a ministry’s website is nowhere to be found. I suspect scientists and think tankers feel the same way. But this is not sloppiness, there is a method to it, as Christiane Kuehl describes today using the energy sector as an example. Figures on electricity production are to be kept secret, is an instruction from the very top. And anyone who wants to look into them nevertheless makes himself a suspect of espionage. Transparency looks different.

The EU Commission has drafted a list of critical technologies the European Union wants to protect from rivals. Digital Commissioner Věra Jourová and EU Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton presented the list in Strasbourg on Tuesday. The list contains a total of ten technologies. However, four of them are designated as particularly dangerous should they fall into the wrong hands:

In addition to these four areas, the list also includes issues such as cybersecurity, sensors, energy, nuclear and fusion technology, robotics and also materials such as nano and smart materials. “Europe is adapting to the new geopolitical realities, putting an end to the era of naivety and acting as a real geopolitical power,” said Commissioner Breton at the presentation.

The list, like the list on critical raw materials, is an element of the economic security strategy first presented by the EU Commission in June. This is the first time Brussels has given its economic policy a security aspect – a fundamental change for the EU, previously based on the concept of free trade.

The EU Commission considers three criteria decisive for the selection of the technologies on these lists. Firstly, the “transformative character” of the technology. By this, the EU Commission means the potential for “radical changes for sectors” by the technology. The second criterion is the risk of dual use, i.e., for civilian and military purposes. The third characteristic is the potential for human rights violations.

However, the question remains about how exactly these technologies will be protected. The EU Commission has not yet specified whether its aim is, for example, to prevent access from third countries to European technology or to better screen European investments in these areas abroad through outbound investment screening. A cross-section has now been found with the list, said Breton. Now, however, he added that it is necessary to take a closer look to fight dependencies.

To this end, a joint risk assessment will be conducted with the 27 member states. “To be a player, we need a united EU position, based on a common assessment of the risks,” said EU Commissioner Jourová.

The lack of a common position became visible, for example, when the Netherlands independently agreed with the US earlier this year to ban the export of advanced chip manufacturing equipment to China. There was subsequent criticism from Brussels and other European capitals that this should have been an EU-wide decision.

While the EU Commission presented its plans, the EU Parliament on Tuesday put its money where its mouth is on another matter: MEPs waved through the Anti Coercion Tool (ACI) with a large majority of votes. “Today we deliver. We’ve filled our toolbox with one additional defensive instrument,” wrote SPD European politician Bernd Lange on X, formerly Twitter. According to Lange, who chairs the parliament’s trade committee, the ACI will come into force in a few weeks.

The background to the new trade instrument was, among other things, Chinese trade restrictions against Lithuania after the government in Vilnius allowed the opening of a “Taiwan office” in Taipei. In such cases, the EU will be able to restrict access to public tenders for companies from the respective countries or block the sale of certain products from Europe. Such steps, however, are meant to be a last resort, when other options, especially diplomatic ones, have been exhausted.

EU Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis welcomed the strong support for the new trade tool. On Tuesday, he answered questions from EU parliamentarians on China trade policy and his recent trip to the People’s Republic. On the latter and the trade dialogue that took place there, Dombrovskis said that there had been no breakthrough, but meaningful steps.

Is China now expanding its anti-espionage campaign to the energy sector? Or is it just an overzealous head of a key government agency? That is what observers wondered after Zhang Jianhua, Director of the National Energy Administration, urged companies in the sector in August to avoid “leaks” in “sensitive areas” of the energy sector, like the nuclear and oil industries. What is certain, however, is that information on China’s energy supply will be harder to obtain than ever before.

Zhang wrote that “hostile foreign forces” were gathering data and information to “distort and defame” China’s energy transition. It remained unclear precisely what he meant by this – but he emphasized the growing risks that he believes emanate from smartphones, social media and hacker attacks. The report, which was unusually harsh for an agency head, was made in the context of China’s broader anti-espionage laws, Bloomberg reported.

Zhang did not mention any names in his text, but seemed to be referring to companies that gather market information, as well as traditional intelligence agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) dealing with energy and climate. He called for more inspections and stricter penalties for violations. Experts reacted to the text with concern. “This does not bode well for data availability, research, media or civil society,” wrote Lauri Myllyvirta, a China expert at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air on X, formerly Twitter.

But only a few days later, Zhang’s post disappeared from the net, as did most of the reports on it in the state media. It was only visible on a few websites, Myllyvirta reported, after he had scoured the net: “As always the deletion is even more interesting than the speech itself.”

China is the world’s largest energy producer and consumer, extracting and burning more than half the world’s coal, importing more oil and gas than any other country – and building the world’s largest solar and wind power plants. China senses espionage in all these areas, if Zhang Jianhua can be taken at his word. Meanwhile, the already limited transparency in China continues to decline, not least because of the country’s economic woes. For example, the National Bureau of Statistics simply no longer releases undesirable data, such as growing youth unemployment.

Since Xi took office in 2012, tens of thousands of the more than 80,000 statistics published each year have been deleted, according to research by the Financial Times. This also includes the environment: “Water data already difficult to get, and if I had to guess, agri data will be next,” says Shanghai environmental consultant Richard Brubaker. But what options does someone who requires these numbers have? Due diligence, market research? However, such in-depth research activities can already be considered illegal under the anti-espionage law.

In any case, in the deleted post, Zhang Jianhua from the energy authority demanded: “We must actively cultivate a culture of confidentiality, keeping secrets and being cautious.” China’s state-owned companies, in particular, don’t need to be told twice. In July, the oil company CNOOC already stated that it held a meeting with fuel traders to increase the confidentiality standards of their work.

For instance, the increasing oil imports from Russia are a matter of secrecy. Chinese customs data showed that China imported 60.66 million tonnes of crude oil from Russia in the first seven months of this year, an increase of roughly 25 percent over the same period last year. But it is unclear who exactly in China is importing this oil.

Most likely, it is the country’s three big state-owned oil companies: China National Petroleum (CNPC), China Petroleum & Chemical (Sinopec) and China National Offshore Oil (CNOOC). But at their recent financial press conferences in Hong Kong, executives from their listed core companies were all very reluctant to give details about their Russian business, according to Nikkei Asia.

So anyone wanting to learn more about China’s oil imports from Russia checks ship trackers or tries to get information in confidential conversations. This is how Bloomberg traced the route of an unregistered oil shipment from Russia’s Ust-Luga in the Baltic Sea to Dongjiakou in China. Such investigations, however, could be considered espionage under Chinese interpretation.

Even information about the energy transition is not as easily obtainable in China as in the USA and Europe. Even though Bloomberg states that government agencies and research companies at least regularly report data that companies, investors and scientists can use as a basis to derive trends for global trade flows and China’s climate efforts.

China owns many patents in the highly subsidized renewable sector, produces solar plants and wind turbines, and is researching electricity storage systems, which are crucial for the energy transition. According to the Japanese newspaper Nikkei Asia, China is currently developing into a hub for research into new types of perovskite solar cells. But access to information is not always so easy, depending on the actor and the location. The operators of large-scale projects such as offshore wind farms or energy storage systems are usually state-owned companies that tend to keep details to a minimum.

The state-owned company Sinopec, for example, started what it claims is the world’s largest plant for the production of green hydrogen in Xinjiang in July. Sinopec announced that its Xinjiang Kuqa Green Hydrogen Pilot Project uses its own photovoltaic plants the size of 900 football fields to produce 20,000 tons of green hydrogen per year from solar energy through water electrolysis. The hydrogen produced will initially be used for oil refining in a nearby chemical plant owned by the company. That’s something, at least.

The Singapore-based specialist website Upstream also reports that the plant features 52 electrolyzers, 13 of which were supplied by a joint venture with Belgian participation. Access to Xinjiang is almost impossible for international market research companies. So, according to Zhang’s interpretation, would it be espionage if a foreigner tried to find out details about the project and its cooperation partners via the Belgian participants?

“Still too early to tell the exact impacts but almost certain that having honest, sincere, and off-script exchanges with CN counterparts would become even more difficult,” Liu Hongqiao, an expert on China’s climate policy, wrote on X after Zhang’s article surfaced. He said it seemed to be not only about data but also about narratives.

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

China is opening its market to pork meat from Russian regions that are free of African swine fever (ASF). This is reported by the news service Agra-Europe. The 15-year import ban by the Chinese customs administration has been lifted. The ban has existed since 2008 after the African swine fever virus ran rampant in Russia. That is why only imports from regions of Russia that are proven to be free of ASF are allowed.

So far, Germany has been trying unsuccessfully to convince China to implement such a solution. And this is even though the People’s Republic is exporting more and more meat. Between January and August 2023, around 1.17 million tons of pork have been imported, almost ten percent more than in the same period last year, according to the Ministry of Agriculture in Beijing. In addition, pork offal imports increased by nearly eight percent to 780,000 tons.

However, these volumes do not come close to the record figures of 2020 and 2021. The biggest suppliers of meat so far this year have been Spain and Brazil, and of by-products the USA and Spain. Henrike Schirmacher

After a three-day break, the shares of the ailing real estate group Evergrande returned to trading on the Hong Kong stock exchange on Tuesday. The share price increased at a low level by as much as 28 percent during the trading day. However, they still only closed at a price of 41 Hong Kong cents, well below the level before China’s real estate crisis.

Evergrande has no prospect of financial recovery in the medium term. Therefore, the share price increase is likely due to short-term speculation with penny stocks. There is no basis for confidence in the company.

The reason for the trading pause was the launch of an investigation in which company CEO Xu Jiayin (Cantonese: Hui Ka-yan) is supposed to participate. He was detained last week. Details were not available. fin

The US technology company Apple is giving in to pressure from China and restricting access to applications in its app store in the People’s Republic. This is reported by the South China Morning Post. In recent days, the American company had still attempted to avert stricter app censorship.

Previously, iPhone owners in China could download and install Western apps via VPN. However, this represented at least a legal gray area, if not a regulatory gap, when it came to banned apps. In the future, only apps licensed by the Ministry of Information MIIT will be listed in the app store. Communication apps such as WhatsApp, X (formerly Twitter), or YouTube could be particularly affected. This will make it more difficult for iPhone users who set up their smartphones in China for the first time to install these apps. fin

Rahile Dawut’s life sentence is symbolic of the plight of Uyghurs in China’s province of Xinjiang. The latest results of Xinjiang investigations show that the number of Uyghur short-term camp detainees has drastically decreased recently. However, in the same period, extremely long prison sentences have increased steeply. However, what may seem like a positive development to outsiders is no reason for hope for the local population. And so, anthropologist Dawut must also assume that she will never live in freedom again.

Despite the odds, Dawut still hoped until recently that her sentence could be overturned. In 2018, a court deemed her a “danger to national security” and found her guilty of “splittism.” Because Dawut’s case, like thousands and thousands of others in the region, was tried behind closed doors, the nature of her offense is unclear.

Recent investigations have revealed that out of a seven-figure number of people sent to the internment and re-education camps by the Chinese government anywhere from a few months to a few years, only a few tens of thousands remain.

However, this does not mean normalization, as the Danish Xinjiang researcher Rune Steenberg claims. The years of mass intimidation are now followed by the systematic disintegration of Uyghur society – in a most perfidious way.

The intellectual elite and several hundred thousand other Uyghurs have been moved to regular prisons and have virtually no prospect of returning to life soon. This emerges from Steenberg’s research. The rest of the population is not only deeply intimidated by the experiences of the past years. They behave as inconspicuously as possible to avoid harsh punishments against themselves and family members.

In addition, they are closely monitored at their workplaces through increasing integration into local industry. The sophisticated technical means of facial recognition, location tracking and communications monitoring have largely replaced internment camps as control instances.

“Rahile Dawut is a secular scholar who is known to have obeyed the laws and regulations of the Chinese government,” says researcher Steenberg about the 57-year-old. He is convinced that neither she nor thousands of other Xinjiang intellectuals can be accused of any ties to terror and extremism.

Dawut’s work as an anthropologist is known far beyond China’s borders. She was an expert on the tradition and culture of the Uyghur ethnic group and taught at Xinjiang University in the regional capital, Urumqi. In 2007, she founded a local research institute on minority customs in China. She gave seminars at renowned universities in the United States and the United Kingdom. In 2020, the academic network Scholars at Risk honored her with the Courage to Think Award. She was also a member of the Communist Party for 30 years.

Her case prompted the US State Department to condemn her detention as unjustified in a statement last week. It is unclear where Dawut is being held, how she is doing, or if she might have had contact with family members in Xinjiang since her arrest in 2017.

At the very least, it became certain a few days ago that she was still alive. But the hope for a reduced sentence is dead. The US human rights foundation Dui Hua has received confirmation from a source in the Chinese government that Dawut’s appeal has been rejected and that her life sentence is now final. grz

Ashwani Muppasani will be the new COO for India and Asia Pacific at car company Stellantis. Muppasani previously headed the National Sales Company for Stellantis in China.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

A flagship store for small plastic figurines? Absolutely. Chinese toy manufacturer Pop Mart International has opened its first flagship store in Thailand’s Central World shopping mall. Pop Mart is one of the largest toy manufacturers in China.