The city of Zheng’an produces six million guitars a year, which makes it something of a global market, considering it’s all produced in one place – even if the instruments are actually built over many small workshops. Thus, news agency Xinhua published a report on Zheng’an on Thursday. The reason: the pandemic has caused a rise in global demand for guitars, with the region seeing a 440 percent increase in sales.

What sounds like an overly specific detail actually stands for the secret of Chinese export success. And this is not only of particular interest for competing for export nations such as Germany, but for other emerging markets as well. The creation of production locations centered around individual product groups has proven to be enormously effective. When several companies are focused on a single place for the same product, in turn, all of them become stronger, Felix Lee analyses.

For weeks, there have been rumors about problems regarding Daimler’s cooperation with Chinese battery manufacturer Farasis. Chairman of the board Ola Källenius has now presented the company’s electric vehicles’ strategy for the coming years. Surprisingly early, the premium manufacturer no longer wants to rely on pure combustion engine cars anymore and instead is planning the construction of several large battery cell plants in preparation. Ambitious – and yet necessary because the Chinese competition is known to be setting a breathtaking pace in the transition to e-mobility. Our analysis reveals what this could mean for collaboration with Farasis.

Daimler’s entry into the electromobility market has been troublesome. In addition to a few hybrid models, the luxury-class manufacturer has so far only offered battery-powered versions of small-series vehicles and its Smart model. The Chinese competition is more than a decade ahead. Under pressure by Chinese authorities, Daimler jointly founded the Denza brand with domestic supplier BYD in 2012, but sales were never particularly high.

Now CEO Ola Källenius is picking up the pace. On Thursday, he and his management team presented the future of e-mobility at Daimler during a one-hour presentation. The company has once again accelerated the transition to battery-electric vehicles significantly. “The tipping point is approaching, especially in the luxury segment, where Mercedes-Benz belongs,” Källenius said. By 2025, not a quarter but half of all products will now be battery-powered. At the end of the decade, the age of the petrol engine will also come to an end at the company whose founder invented it.

However, this presents Daimler with considerable problems in the procurement of the needed batteries for its entire annual production. The company apparently may already manufacture its own batteries at its subsidiary “Deutsche Accumotive”. But they continue to purchase the core of their energy storage devices, the battery cell. Last year, the company announced that it was planning a battery factory in Bitterfeld in Saxony-Anhalt with its Chinese partner Farasis Energy.

Källenius is now kicking things up a notch. Daimler now plans to build eight “gigafactories” around the globe – borrowing not only the idea but also the term from rival Tesla. Four of the planned factories will be built in Europe. A new partner is to be involved in these projects, but was not named. Källenius merely promised to make its name public soon.

Building own battery cell factories is a change in strategy. Until now, Daimler had relied on sourcing and partnerships. The company had already entered the battery cell manufacturing business once in the past and then dropped out again for cost reasons. Announcing eight factories now is a huge step. Tesla only has three of them and is planning two additional factories while Volkswagen is planning six large battery cell factories.

The sudden announcement of a massive entry into battery cell production leads to one question: What will become of Daimler’s collaboration with Farasis? It was striking that Källenius and his team did not mention the name of the recently proudly praised partner company once during the presentation. Daimler, on the other hand, intends to make its new European partner for battery cell production public in the coming days, as company representatives stressed again after the presentation during an investor call.

A year ago, Daimler and Farasis announced a “strategic partnership“. “The agreement offers Mercedes-Benz a reliable supply of battery cells for its electric offensive,” the company happily announced at the time, sealing the deal with a small equity investment in Farasis. But in February, rumors surfaced that Farasis’ battery cells were not of sufficient quality for Daimler. Later, the Handelsblatt reported that a departure from Farasis was imminent.

A company spokeswoman now reiterated that “Farasis is a strategic partner for Mercedes-Benz battery cells” and that nothing has changed. The reports about the poor quality of battery cell samples were false, she added. “Daimler Greater China’s partnership with Farasis remains unchanged.” The mention of Daimler Greater China here is striking. Within the same statement, the spokeswoman stressed that Mercedes-Benz had built up “a well-functioning and very stable supplier set for battery cells” – without mentioning Farasis again as an important part of its network. Farasis also did not play any role in a conversation between Daimler executives and analysts.

So Daimler is now apparently following both paths: the group is building its own factories, but at the same time seems to continue its cooperation with Farasis. At least for the large Chinese market, Daimler can make good use of locally manufactured batteries. It also has technology for particularly powerful batteries with outstanding energy density.

The fate of the planned factory in Bitterfeld, however, remains unknown. Hopes were raised in the region that an important employer would settle here. But according to the original schedule, production was supposed to start in 2022 – with nothing happening yet. Not even Tesla builds factories this quickly. So Farasis production in Eastern Germany will be delayed at best, yet it may also become one of the eight Gigafactory locations. After all, Daimler is explicitly cooperating with partner companies for this very purpose.

Daimler’s change in strategy to large-scale production under their own management fits the overall trend to break away from dependence on Asian technology. For a while it seemed like any German car could hardly run without Chinese batteries: BMW cooperated with the global market leader CATL from Ningde, Daimler with Farasis from Ganzhou and Volkswagen also relied on Chinese partners. But VW spearheaded a new approach and teamed up with Swedish supplier Northvolt for the European market. The Wolfsburg company is now planning to construct six Gigafactories around the globe.

For the time being, German manufacturers will definitely stay in touch with their Chinese battery cell partners – if only for production in China, their largest market. At the same time, however, a downward trend can be seen in the other markets. This is not surprising. After all, the battery is the heart of any electric vehicle and its range is a powerful selling point. And if an increasingly aggressive China would suddenly forbid its suppliers to cooperate with Germany, production could come to a grinding halt if no alternatives are available.

With a population of just 800,000, Danyang is considered a rather small city by Chinese standards. Located on the edge of the Yangtze Delta, it tends to stand in the shadow of booming cities like Shanghai, Suzhou, Nanjing and Hangzhou. And yet, Danyang is an economic heavyweight. Today, around half of all eyeglass lenses produced worldwide, including sunglasses, are being produced in Danyang. In China, Danyang is therefore also known as the “City of Glasses”.

Danyang is a particularly impressive example of how China has managed to transform itself from a backward economy to the world’s technological leader within just a few decades. And this is just one of many examples. Economists Aoife Hanley from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) and Gong Yundang from King’s College in London have studied this phenomenon in detail. Their survey has evaluated data of 170,000 companies in China. The conclusion: The strongly export-oriented approach of Chinese companies across many sectors has contributed significantly to their success. According to the study, a surge in innovation can be observed in companies that mainly focus on exports.

An even more exemplary success story for China is the city of Shenzhen, located on the Pearl River Delta in southern China. By the end of the 1970s, a small fishing village bordering the then British Crown Colony of Hong Kong, Shenzhen slowly became “the workbench of the world”, focusing primarily on the production of sporting goods, plastic toys and cheap electronics. Today, not only 90 percent of all e-cigarettes are being produced in Shenzhen, but the city is also one of the most innovative metropolises in the world and, with its myriad of tech companies, has long since rivaled Silicon Valley.

The development history of these economic centers is all similar. At the beginning of the 1980s, Danyang only harbored few manufacturers of glass lenses. As the economy continued to open up to the rest of the world, their numbers grew. The city government encouraged the foundation of additional factories by establishing the first Glasses Market in 1986. At that time, it mainly consisted of market stalls where manufacturers offered their glasses. Later, the stalls were replaced by a shopping mall with hundreds of eyeglass shops. But that’s not all: Today, the entire city is filled with eyeglass shops and production facilities. If you combine them all, the companies of Danyang are the global market leader.

Economist Hanley refers to this type of industrial development as “spillovers through labor mobility”, when several companies all concentrate in one place for the same product. The employees of each company will then specialize. The arrival of other competing firms in no way results in a displacement effect. On the contrary, through exchanges between employees of similar companies producing the same product, workers acquire additional skills and transfer knowledge. In addition, competitive pressure increases – which generates further innovations.

However, experts see the most important effect in physical proximity. “Highly specialized employees in a city like Danyang know each other’s work – and thus acquire valuable skills,” Hanley explains. In her observation, “Labour spillovers” occur above all when companies are located in the same city. At the same time, synergy effects emerge, for example, with the construction of infrastructure such as port and rail facilities for exporting goods. “Is one company in Danyang able to produce lenses of higher quality if the whole neighborhood is geared up for exports? The answer is definite yes,” says Hanley .

In fact, this type of industrial development has a long-standing tradition in China. As early as the Song Dynasty (10th to 13th centuries), the inhabitants of the city of Jingdezhen specialized in the production of ceramics. To this day, Jingdezhen is considered the capital of porcelain. And this kind of concentration of an entire industry branch in one place can also be observed in other Chinese cities. The city of Haining, also located in the Yangtze Delta, specializes in leather processing. The city of Yiwu is the world’s largest exporter of Christmas articles. Yet, Christmas is not celebrated at all in China.

Another thing the authors discovered was that companies that overall did not seem very creative or innovative were suddenly part of an innovation offensive when they were located in the same area as successful exporting companies (export processing). “It’s an important discovery,” says Hanley. “Export processing can also be a path leading to more innovation.”

Is China’s export model also suitable for other developing countries? Hanley would be inclined to agree. Special economic zones with special tax rates or other benefits, like the countless ones set up all over China, have also been adopted by countries such as South Africa with its Dube TradePort in Durban. And yes, these zones are also successful in terms of exports and are proving to be highly innovative.

The central Chinese province of Henan is threatened by continued extreme rainfall. Yesterday, the provincial weather bureau issued a severe weather warning of the highest level for the megacities of Xinxiang, Anyang, Hebi and Jiaozuo in northern Henan. Tens of thousands of people were evacuated. Anyang has seen precipitation over 600 millimeters since Monday. In the city of Xinxiang, with a population of more than five million, precipitation from Tuesday to Thursday was as high as 800 millimeters. Seven medium-sized reservoirs within the city overflowed, as Reuters reported. In the province of Henan, floods had killed 33 people by Thursday and more than three million were left homeless, according to Henan authorities. Electricity and drinking water supplies have failed in several regions. Many villages remain trapped by water.

Chen Tao, chief meteorologist of the National Meteorological Center, said China has made efforts to improve its extreme weather forecasts. “There are many uncertainties in extreme weather systems that can affect the accuracy of a forecast,” Tao told the South China Morning Post. Meteorologists had forecast heavy rains but issued warnings for the wrong cities and times. China had no emergency mechanisms in place once the highest severe weather alert was issued, said Cheng Xiaotao, former director of the Institute of Flood Control and Disaster Prevention at the China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, according to the Financial Times.

The flood disaster in Henan also has an economic impact. The provincial capital of Zhengzhou is a central hub in China’s railway infrastructure. The transport of coal from Inner Mongolia and Shanxi to central and eastern China has been “severely affected”, according to authorities. This is hitting power plants particularly hard as power grids struggle with high demand during summer (as China.Table reported). The local airport is also a major transshipment point for air cargo.

SAIC Motors and Nissan issued statements that floods would impair their production in Zhengzhou. Apple also produces iPhones in Zhengzhou. Agriculture has also been affected. Within the province, 200,000 hectares of agricultural land have been flooded. An area more than twice the size of Berlin. Henan harvests a quarter of all peanuts produced in China. Last year, the aftermath of heavy rain was also responsible for another outbreak of African swine fever in China, Reuters reported. Now the risk of a renewed spread of animal diseases is increasing.

On Thursday, Premier Li Keqiang announced a set of measures against flood disasters. Key points include better flood management on rivers and lakes, improved forecasts of heavy rain and its consequences, the preparation of crisis plans and the establishment of emergency infrastructure. nib

China has strongly rejected a plan by the World Health Organization (WHO) to investigate laboratories in Wuhan in search of the origin of COVID-19. The WHO’s plan disregards “some aspects of common sense” and “defies science,” Zeng Yixin, vice-minister of the National Health Commission, told journalists on Thursday, according to a Reuters report. He was stunned by the WHO’s plans, which included the theory that the virus could have originated in a laboratory, Zeng said.

On Friday, WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus had stressed in Geneva that in addition to the investigation of wild animals and animal markets in the Chinese city of Wuhan, local laboratories must also be inspected (China.Table reported). The WHO chief had also reprimanded China in early July for obstructing the investigation by withholding data. According to the report, Zeng reiterated China’s stance that certain information could not be fully shared for security reasons. “We hope the WHO will review the considerations and suggestions of Chinese experts in all seriousness and truly treat the origin of COVID-19 virus as a scientific matter and eliminate political interference,” Zeng said.

In a report by the WHO on the origin of the Covid virus, experts had labeled the theory of a laboratory leak as ‘very unlikely’. However, the US government in particular is pushing for further investigation of this thesis. “The expert team agreed unanimously that it is extremely unlikely the virus leaked from the lab, so future virus origin tracing missions will no longer be focused on this area, unless there is new evidence,” said Liang Wannian, the Chinese team leader on the WHO investigation team. More animal testing should be done, especially in countries with bat populations, Liang stressed. ari

Yesterday, Hong Kong police arrested five people on sedition charges. They are accused of inciting hatred against the city’s government by publishing certain children’s books, news agency Reuters reported. According to the report, police stated that in one of the books, wolves attacked a village while the sheep living there defended themselves. This story was linked to protests against the government, authorities had claimed. The five individuals, aged between 25 and 28, were arrested on suspicion of conspiracy to publish seditious material. The charge is based on a colonial-era law.

On Wednesday, the former managing editor of the now-closed Apple Daily newspaper Lam Man Chung was arrested on suspicion of “conspiring to collaborate with foreign countries or foreign forces to endanger national security,” Reuters reported. Earlier, police had arrested seven other editors. A court yesterday rejected a request for the release on bail of Lam and three other newspaper employees. The trial was adjourned until September 30. nib

Gone are the days when Western news anchors were given stage directions on how to pronounce Xi Jinping’s last name, “like the word ski.” Today, the name is familiar to them, after all, dozens of biographies have long been published about China’s most powerful leader since Mao.

But anyone who tries to understand the person behind the facade China has built around its head of state is still left in the dark. Since Jinping ascended to party and state leadership at the end of 2012, he no longer agrees to interviews and does not reveal any details on his life. Apart from official speeches on important occasions or on foreign trips, his other essays and speeches are only published by the propaganda machine after a considerable time and usually selected passages only.

As a provincial official, he was more informal, even to reporters. He spoke about his privileged childhood and later bitter youth after his revolutionary father Xi Zhongxun fell into political disfavor with Mao in 1962 and was not rehabilitated until 1978. The whole family was placed under collective arrest. Xi’s earlier interviews are one of the very few sources that help in understanding his personality.

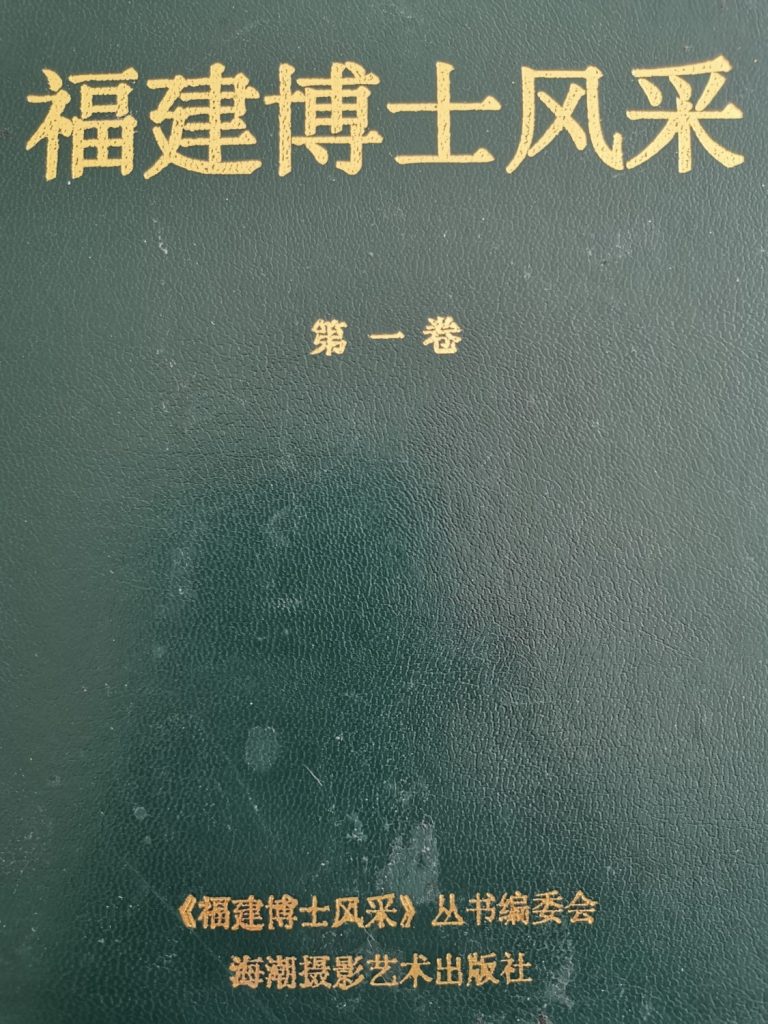

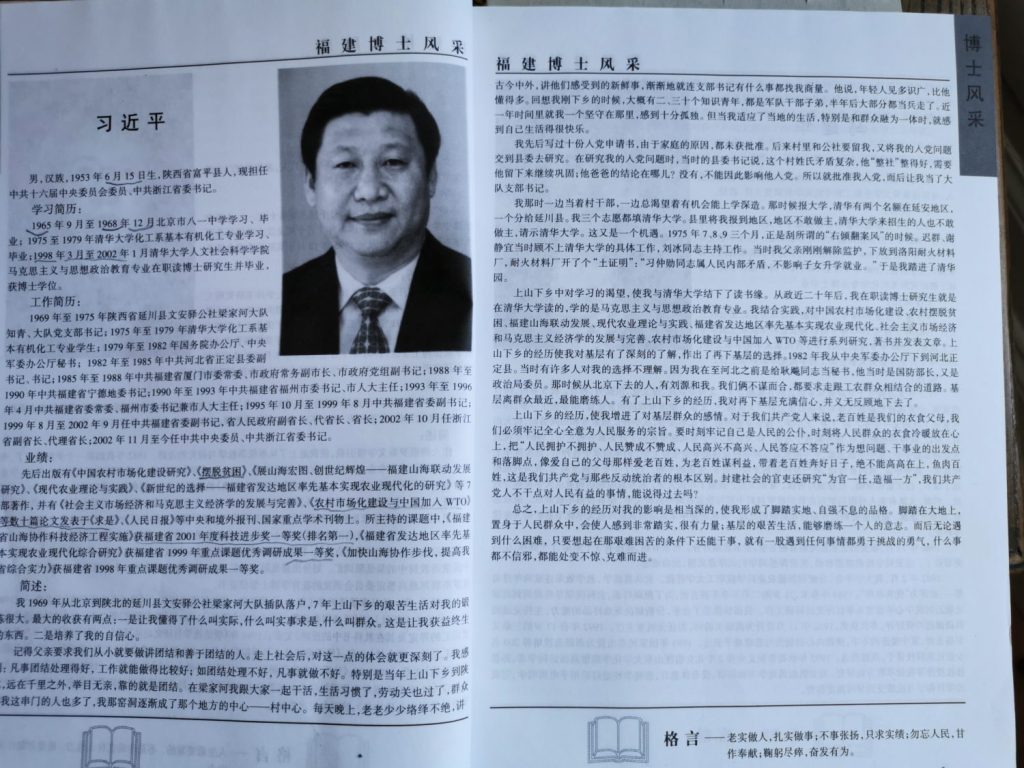

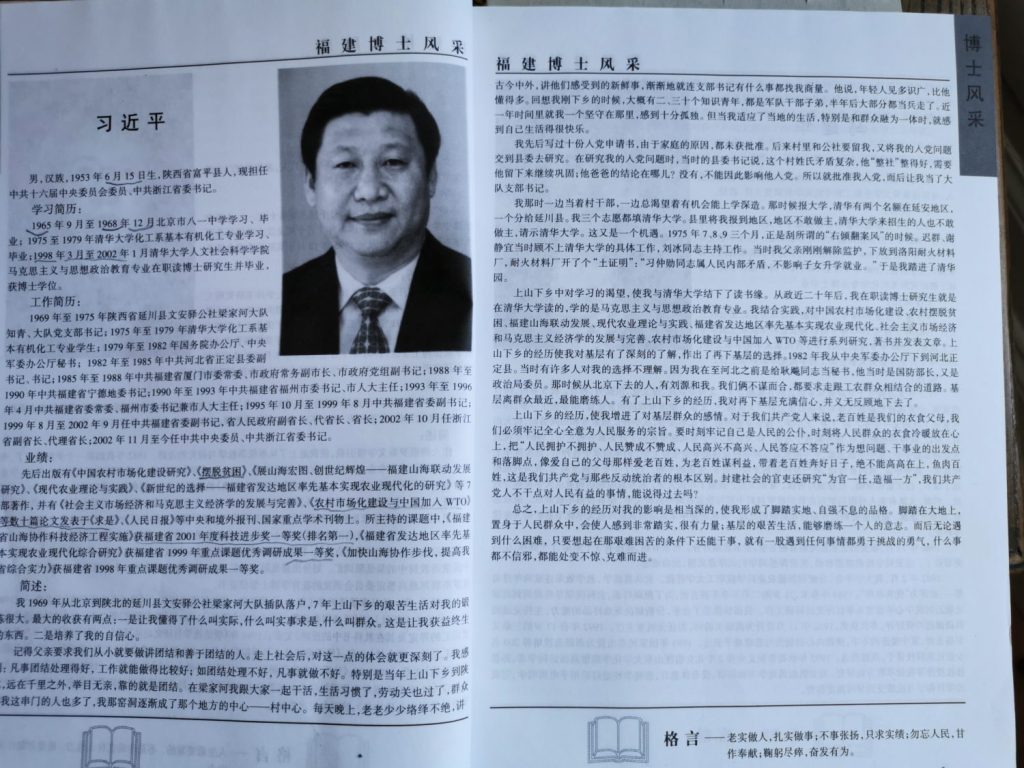

This also applies to a curriculum vitae written by none other than Xi himself. He wrote it for an encyclopedia of biographies, published in 2003, on 381 doctoral students from Fujian, whose academic talent the coastal province wanted to boast about. Xi, who ruled the province as vice chief and then governor from August 1999 to September 2002, also chaired the advisory committee to edit the encyclopedia (福建博士风采), ranking himself among the 381 doctoral students and wrote an article about himself spanning two pages. In it, he revealed that he was a doctoral student at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of Tsinghua University in Beijing from March 1998 to January 2002. He earned a doctorate for his thesis, “A Tentative Study on China’s Rural Marketization.” He does not reveal how he (and if he himself) managed to earn the doctorate while simultaneously working a full-time job as provincial chief of Fujian.

I discovered the encyclopedia, which was published publicly in June 2003 with a release of 2,000 copies, in a second-hand bookshop in Beijing. In it, Xi describes his career in the first person. After being forced to drop out of his Beijing middle school education as a 15-year-old amidst the chaos of the Cultural Revolution in December 1968, he spent the next seven years until 1975 working in the fields in a village brigade in North China’s Shanxi province.

Xi’s curriculum vitae begins like this: “In 1969, I arrived from Beijing in the Liangjiahe Production Brigade of the Wenanyi People’s Commune to ‘put down roots’. (…) I was very far from home, without any relatives. (…) At first, we were 20 to 30 school-educated youths who came to the village. All of them came from functionary military families. After half a year, most of them left again, they went into army service. After a year, they were all gone. Only I stayed behind. I felt very lonely.”

For the first time, Xi reveals how he repeatedly tried in vain to be allowed to join the Party during his seven years in the countryside. He was not allowed to join because of his father’s political persecution. “I wrote ten applications to join the Party. But they were rejected because of my family situation.” (我先后写过十份入党申请书,由于家庭的原因,都未.) Today, Xi surely must take great satisfaction in the fact that the party, which only admitted him in 1974, has more than tripled in size from just under 30 million members at the time to 95 million and obeys unconditionally. He even had their statutes amended to enshrine his “Xi Jinping Thought” in writing as a guiding ideology for the new era.

Back when Xi was a young farmer, he faced all the adversities of rural life and worked hard. This is how he finally was accepted by the village community: “Every evening, old and young farmers came to me, chatted with me about history and the current situation. (…) the cave I lived in became a meeting place. Even the party secretary of the brigade came to confer with me. (…) Eventually, he approved my party admission. He made sure that I later became the head of the party cell in our village.”

Xi now hoped to be allowed to study in Beijing. Tsinghua University had offered two spots for the entire farming region in 1975. Xi was nominated by his village. But because of his politically ostracized father, he was blocked by the next level of hierarchy: “The university official in charge of farmer students didn’t dare to make a decision. He forwarded my application to the top university management. They were supposed to decide.” Xi writes, “but this became my chance since Tsinghua University was caught in the vortex of a cultural-revolutionary political campaign against the so-called ‘right winds of restoration’ in July, August, and September 1975.” The two (ultra-leftist) university leaders, who he names as Chi Qun and Xie Chengyi, had no time to attend to newly admitted students, and so Xi, a farmer student, eluded their attention. He writes: “At this time my father had just come out of exile and was sent to work in a factory in Luoyang. This factory then turned to me in a letter to Tsinghua: ‘Comrade Xi Zhongxun’s problems are among the people’s contradictions. They should not prevent his children from studying or working.’ It was enough of a letter of recommendation for me to attend university.”

Xi studied chemistry. When he graduated in 1979, he was hired as a secretary by then defense minister and political bureau member Geng Biao (a friend of Xi’s now fully rehabilitated father). But at his own request, Xi transferred to the county seat of Zhengding in the province of Hebei in 1982 and started in the position of vice party secretary. He recounts that at the time, many did not understand why he was leaving Beijing. “Besides me, others went back to the lowest administrative level as well, Liu Yuan for example, (Son of Liu Shaoqi, the former state president persecuted to death by Mao). Independently, we both came to the same conclusion to join the workers and peasants.”

In fact, working in the provinces is a classic way to make a political career in the People’s Republic. Starting in 1982, Xi’s 25-year ascent began across four provinces until he reached the center of power in Beijing in 2007.

In his CV, written in 2003, at no point, Xi critically reflects on what happened to him, even as he admits to having been treated unfairly. He concludes that his seven years of experience in the countryside made him a “down-to-earth” man. He is “not prone to false doctrines,” is not shaken by anything, and will go any distance to “to get ahead.”

Today, at 12:00 PM CEST, the Olympic Games will start in Tokyo. Athletes are already preparing in their respective disciplines, like athlete Zeng Wenhui of the Chinese skateboarding team.

The city of Zheng’an produces six million guitars a year, which makes it something of a global market, considering it’s all produced in one place – even if the instruments are actually built over many small workshops. Thus, news agency Xinhua published a report on Zheng’an on Thursday. The reason: the pandemic has caused a rise in global demand for guitars, with the region seeing a 440 percent increase in sales.

What sounds like an overly specific detail actually stands for the secret of Chinese export success. And this is not only of particular interest for competing for export nations such as Germany, but for other emerging markets as well. The creation of production locations centered around individual product groups has proven to be enormously effective. When several companies are focused on a single place for the same product, in turn, all of them become stronger, Felix Lee analyses.

For weeks, there have been rumors about problems regarding Daimler’s cooperation with Chinese battery manufacturer Farasis. Chairman of the board Ola Källenius has now presented the company’s electric vehicles’ strategy for the coming years. Surprisingly early, the premium manufacturer no longer wants to rely on pure combustion engine cars anymore and instead is planning the construction of several large battery cell plants in preparation. Ambitious – and yet necessary because the Chinese competition is known to be setting a breathtaking pace in the transition to e-mobility. Our analysis reveals what this could mean for collaboration with Farasis.

Daimler’s entry into the electromobility market has been troublesome. In addition to a few hybrid models, the luxury-class manufacturer has so far only offered battery-powered versions of small-series vehicles and its Smart model. The Chinese competition is more than a decade ahead. Under pressure by Chinese authorities, Daimler jointly founded the Denza brand with domestic supplier BYD in 2012, but sales were never particularly high.

Now CEO Ola Källenius is picking up the pace. On Thursday, he and his management team presented the future of e-mobility at Daimler during a one-hour presentation. The company has once again accelerated the transition to battery-electric vehicles significantly. “The tipping point is approaching, especially in the luxury segment, where Mercedes-Benz belongs,” Källenius said. By 2025, not a quarter but half of all products will now be battery-powered. At the end of the decade, the age of the petrol engine will also come to an end at the company whose founder invented it.

However, this presents Daimler with considerable problems in the procurement of the needed batteries for its entire annual production. The company apparently may already manufacture its own batteries at its subsidiary “Deutsche Accumotive”. But they continue to purchase the core of their energy storage devices, the battery cell. Last year, the company announced that it was planning a battery factory in Bitterfeld in Saxony-Anhalt with its Chinese partner Farasis Energy.

Källenius is now kicking things up a notch. Daimler now plans to build eight “gigafactories” around the globe – borrowing not only the idea but also the term from rival Tesla. Four of the planned factories will be built in Europe. A new partner is to be involved in these projects, but was not named. Källenius merely promised to make its name public soon.

Building own battery cell factories is a change in strategy. Until now, Daimler had relied on sourcing and partnerships. The company had already entered the battery cell manufacturing business once in the past and then dropped out again for cost reasons. Announcing eight factories now is a huge step. Tesla only has three of them and is planning two additional factories while Volkswagen is planning six large battery cell factories.

The sudden announcement of a massive entry into battery cell production leads to one question: What will become of Daimler’s collaboration with Farasis? It was striking that Källenius and his team did not mention the name of the recently proudly praised partner company once during the presentation. Daimler, on the other hand, intends to make its new European partner for battery cell production public in the coming days, as company representatives stressed again after the presentation during an investor call.

A year ago, Daimler and Farasis announced a “strategic partnership“. “The agreement offers Mercedes-Benz a reliable supply of battery cells for its electric offensive,” the company happily announced at the time, sealing the deal with a small equity investment in Farasis. But in February, rumors surfaced that Farasis’ battery cells were not of sufficient quality for Daimler. Later, the Handelsblatt reported that a departure from Farasis was imminent.

A company spokeswoman now reiterated that “Farasis is a strategic partner for Mercedes-Benz battery cells” and that nothing has changed. The reports about the poor quality of battery cell samples were false, she added. “Daimler Greater China’s partnership with Farasis remains unchanged.” The mention of Daimler Greater China here is striking. Within the same statement, the spokeswoman stressed that Mercedes-Benz had built up “a well-functioning and very stable supplier set for battery cells” – without mentioning Farasis again as an important part of its network. Farasis also did not play any role in a conversation between Daimler executives and analysts.

So Daimler is now apparently following both paths: the group is building its own factories, but at the same time seems to continue its cooperation with Farasis. At least for the large Chinese market, Daimler can make good use of locally manufactured batteries. It also has technology for particularly powerful batteries with outstanding energy density.

The fate of the planned factory in Bitterfeld, however, remains unknown. Hopes were raised in the region that an important employer would settle here. But according to the original schedule, production was supposed to start in 2022 – with nothing happening yet. Not even Tesla builds factories this quickly. So Farasis production in Eastern Germany will be delayed at best, yet it may also become one of the eight Gigafactory locations. After all, Daimler is explicitly cooperating with partner companies for this very purpose.

Daimler’s change in strategy to large-scale production under their own management fits the overall trend to break away from dependence on Asian technology. For a while it seemed like any German car could hardly run without Chinese batteries: BMW cooperated with the global market leader CATL from Ningde, Daimler with Farasis from Ganzhou and Volkswagen also relied on Chinese partners. But VW spearheaded a new approach and teamed up with Swedish supplier Northvolt for the European market. The Wolfsburg company is now planning to construct six Gigafactories around the globe.

For the time being, German manufacturers will definitely stay in touch with their Chinese battery cell partners – if only for production in China, their largest market. At the same time, however, a downward trend can be seen in the other markets. This is not surprising. After all, the battery is the heart of any electric vehicle and its range is a powerful selling point. And if an increasingly aggressive China would suddenly forbid its suppliers to cooperate with Germany, production could come to a grinding halt if no alternatives are available.

With a population of just 800,000, Danyang is considered a rather small city by Chinese standards. Located on the edge of the Yangtze Delta, it tends to stand in the shadow of booming cities like Shanghai, Suzhou, Nanjing and Hangzhou. And yet, Danyang is an economic heavyweight. Today, around half of all eyeglass lenses produced worldwide, including sunglasses, are being produced in Danyang. In China, Danyang is therefore also known as the “City of Glasses”.

Danyang is a particularly impressive example of how China has managed to transform itself from a backward economy to the world’s technological leader within just a few decades. And this is just one of many examples. Economists Aoife Hanley from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) and Gong Yundang from King’s College in London have studied this phenomenon in detail. Their survey has evaluated data of 170,000 companies in China. The conclusion: The strongly export-oriented approach of Chinese companies across many sectors has contributed significantly to their success. According to the study, a surge in innovation can be observed in companies that mainly focus on exports.

An even more exemplary success story for China is the city of Shenzhen, located on the Pearl River Delta in southern China. By the end of the 1970s, a small fishing village bordering the then British Crown Colony of Hong Kong, Shenzhen slowly became “the workbench of the world”, focusing primarily on the production of sporting goods, plastic toys and cheap electronics. Today, not only 90 percent of all e-cigarettes are being produced in Shenzhen, but the city is also one of the most innovative metropolises in the world and, with its myriad of tech companies, has long since rivaled Silicon Valley.

The development history of these economic centers is all similar. At the beginning of the 1980s, Danyang only harbored few manufacturers of glass lenses. As the economy continued to open up to the rest of the world, their numbers grew. The city government encouraged the foundation of additional factories by establishing the first Glasses Market in 1986. At that time, it mainly consisted of market stalls where manufacturers offered their glasses. Later, the stalls were replaced by a shopping mall with hundreds of eyeglass shops. But that’s not all: Today, the entire city is filled with eyeglass shops and production facilities. If you combine them all, the companies of Danyang are the global market leader.

Economist Hanley refers to this type of industrial development as “spillovers through labor mobility”, when several companies all concentrate in one place for the same product. The employees of each company will then specialize. The arrival of other competing firms in no way results in a displacement effect. On the contrary, through exchanges between employees of similar companies producing the same product, workers acquire additional skills and transfer knowledge. In addition, competitive pressure increases – which generates further innovations.

However, experts see the most important effect in physical proximity. “Highly specialized employees in a city like Danyang know each other’s work – and thus acquire valuable skills,” Hanley explains. In her observation, “Labour spillovers” occur above all when companies are located in the same city. At the same time, synergy effects emerge, for example, with the construction of infrastructure such as port and rail facilities for exporting goods. “Is one company in Danyang able to produce lenses of higher quality if the whole neighborhood is geared up for exports? The answer is definite yes,” says Hanley .

In fact, this type of industrial development has a long-standing tradition in China. As early as the Song Dynasty (10th to 13th centuries), the inhabitants of the city of Jingdezhen specialized in the production of ceramics. To this day, Jingdezhen is considered the capital of porcelain. And this kind of concentration of an entire industry branch in one place can also be observed in other Chinese cities. The city of Haining, also located in the Yangtze Delta, specializes in leather processing. The city of Yiwu is the world’s largest exporter of Christmas articles. Yet, Christmas is not celebrated at all in China.

Another thing the authors discovered was that companies that overall did not seem very creative or innovative were suddenly part of an innovation offensive when they were located in the same area as successful exporting companies (export processing). “It’s an important discovery,” says Hanley. “Export processing can also be a path leading to more innovation.”

Is China’s export model also suitable for other developing countries? Hanley would be inclined to agree. Special economic zones with special tax rates or other benefits, like the countless ones set up all over China, have also been adopted by countries such as South Africa with its Dube TradePort in Durban. And yes, these zones are also successful in terms of exports and are proving to be highly innovative.

The central Chinese province of Henan is threatened by continued extreme rainfall. Yesterday, the provincial weather bureau issued a severe weather warning of the highest level for the megacities of Xinxiang, Anyang, Hebi and Jiaozuo in northern Henan. Tens of thousands of people were evacuated. Anyang has seen precipitation over 600 millimeters since Monday. In the city of Xinxiang, with a population of more than five million, precipitation from Tuesday to Thursday was as high as 800 millimeters. Seven medium-sized reservoirs within the city overflowed, as Reuters reported. In the province of Henan, floods had killed 33 people by Thursday and more than three million were left homeless, according to Henan authorities. Electricity and drinking water supplies have failed in several regions. Many villages remain trapped by water.

Chen Tao, chief meteorologist of the National Meteorological Center, said China has made efforts to improve its extreme weather forecasts. “There are many uncertainties in extreme weather systems that can affect the accuracy of a forecast,” Tao told the South China Morning Post. Meteorologists had forecast heavy rains but issued warnings for the wrong cities and times. China had no emergency mechanisms in place once the highest severe weather alert was issued, said Cheng Xiaotao, former director of the Institute of Flood Control and Disaster Prevention at the China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, according to the Financial Times.

The flood disaster in Henan also has an economic impact. The provincial capital of Zhengzhou is a central hub in China’s railway infrastructure. The transport of coal from Inner Mongolia and Shanxi to central and eastern China has been “severely affected”, according to authorities. This is hitting power plants particularly hard as power grids struggle with high demand during summer (as China.Table reported). The local airport is also a major transshipment point for air cargo.

SAIC Motors and Nissan issued statements that floods would impair their production in Zhengzhou. Apple also produces iPhones in Zhengzhou. Agriculture has also been affected. Within the province, 200,000 hectares of agricultural land have been flooded. An area more than twice the size of Berlin. Henan harvests a quarter of all peanuts produced in China. Last year, the aftermath of heavy rain was also responsible for another outbreak of African swine fever in China, Reuters reported. Now the risk of a renewed spread of animal diseases is increasing.

On Thursday, Premier Li Keqiang announced a set of measures against flood disasters. Key points include better flood management on rivers and lakes, improved forecasts of heavy rain and its consequences, the preparation of crisis plans and the establishment of emergency infrastructure. nib

China has strongly rejected a plan by the World Health Organization (WHO) to investigate laboratories in Wuhan in search of the origin of COVID-19. The WHO’s plan disregards “some aspects of common sense” and “defies science,” Zeng Yixin, vice-minister of the National Health Commission, told journalists on Thursday, according to a Reuters report. He was stunned by the WHO’s plans, which included the theory that the virus could have originated in a laboratory, Zeng said.

On Friday, WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus had stressed in Geneva that in addition to the investigation of wild animals and animal markets in the Chinese city of Wuhan, local laboratories must also be inspected (China.Table reported). The WHO chief had also reprimanded China in early July for obstructing the investigation by withholding data. According to the report, Zeng reiterated China’s stance that certain information could not be fully shared for security reasons. “We hope the WHO will review the considerations and suggestions of Chinese experts in all seriousness and truly treat the origin of COVID-19 virus as a scientific matter and eliminate political interference,” Zeng said.

In a report by the WHO on the origin of the Covid virus, experts had labeled the theory of a laboratory leak as ‘very unlikely’. However, the US government in particular is pushing for further investigation of this thesis. “The expert team agreed unanimously that it is extremely unlikely the virus leaked from the lab, so future virus origin tracing missions will no longer be focused on this area, unless there is new evidence,” said Liang Wannian, the Chinese team leader on the WHO investigation team. More animal testing should be done, especially in countries with bat populations, Liang stressed. ari

Yesterday, Hong Kong police arrested five people on sedition charges. They are accused of inciting hatred against the city’s government by publishing certain children’s books, news agency Reuters reported. According to the report, police stated that in one of the books, wolves attacked a village while the sheep living there defended themselves. This story was linked to protests against the government, authorities had claimed. The five individuals, aged between 25 and 28, were arrested on suspicion of conspiracy to publish seditious material. The charge is based on a colonial-era law.

On Wednesday, the former managing editor of the now-closed Apple Daily newspaper Lam Man Chung was arrested on suspicion of “conspiring to collaborate with foreign countries or foreign forces to endanger national security,” Reuters reported. Earlier, police had arrested seven other editors. A court yesterday rejected a request for the release on bail of Lam and three other newspaper employees. The trial was adjourned until September 30. nib

Gone are the days when Western news anchors were given stage directions on how to pronounce Xi Jinping’s last name, “like the word ski.” Today, the name is familiar to them, after all, dozens of biographies have long been published about China’s most powerful leader since Mao.

But anyone who tries to understand the person behind the facade China has built around its head of state is still left in the dark. Since Jinping ascended to party and state leadership at the end of 2012, he no longer agrees to interviews and does not reveal any details on his life. Apart from official speeches on important occasions or on foreign trips, his other essays and speeches are only published by the propaganda machine after a considerable time and usually selected passages only.

As a provincial official, he was more informal, even to reporters. He spoke about his privileged childhood and later bitter youth after his revolutionary father Xi Zhongxun fell into political disfavor with Mao in 1962 and was not rehabilitated until 1978. The whole family was placed under collective arrest. Xi’s earlier interviews are one of the very few sources that help in understanding his personality.

This also applies to a curriculum vitae written by none other than Xi himself. He wrote it for an encyclopedia of biographies, published in 2003, on 381 doctoral students from Fujian, whose academic talent the coastal province wanted to boast about. Xi, who ruled the province as vice chief and then governor from August 1999 to September 2002, also chaired the advisory committee to edit the encyclopedia (福建博士风采), ranking himself among the 381 doctoral students and wrote an article about himself spanning two pages. In it, he revealed that he was a doctoral student at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of Tsinghua University in Beijing from March 1998 to January 2002. He earned a doctorate for his thesis, “A Tentative Study on China’s Rural Marketization.” He does not reveal how he (and if he himself) managed to earn the doctorate while simultaneously working a full-time job as provincial chief of Fujian.

I discovered the encyclopedia, which was published publicly in June 2003 with a release of 2,000 copies, in a second-hand bookshop in Beijing. In it, Xi describes his career in the first person. After being forced to drop out of his Beijing middle school education as a 15-year-old amidst the chaos of the Cultural Revolution in December 1968, he spent the next seven years until 1975 working in the fields in a village brigade in North China’s Shanxi province.

Xi’s curriculum vitae begins like this: “In 1969, I arrived from Beijing in the Liangjiahe Production Brigade of the Wenanyi People’s Commune to ‘put down roots’. (…) I was very far from home, without any relatives. (…) At first, we were 20 to 30 school-educated youths who came to the village. All of them came from functionary military families. After half a year, most of them left again, they went into army service. After a year, they were all gone. Only I stayed behind. I felt very lonely.”

For the first time, Xi reveals how he repeatedly tried in vain to be allowed to join the Party during his seven years in the countryside. He was not allowed to join because of his father’s political persecution. “I wrote ten applications to join the Party. But they were rejected because of my family situation.” (我先后写过十份入党申请书,由于家庭的原因,都未.) Today, Xi surely must take great satisfaction in the fact that the party, which only admitted him in 1974, has more than tripled in size from just under 30 million members at the time to 95 million and obeys unconditionally. He even had their statutes amended to enshrine his “Xi Jinping Thought” in writing as a guiding ideology for the new era.

Back when Xi was a young farmer, he faced all the adversities of rural life and worked hard. This is how he finally was accepted by the village community: “Every evening, old and young farmers came to me, chatted with me about history and the current situation. (…) the cave I lived in became a meeting place. Even the party secretary of the brigade came to confer with me. (…) Eventually, he approved my party admission. He made sure that I later became the head of the party cell in our village.”

Xi now hoped to be allowed to study in Beijing. Tsinghua University had offered two spots for the entire farming region in 1975. Xi was nominated by his village. But because of his politically ostracized father, he was blocked by the next level of hierarchy: “The university official in charge of farmer students didn’t dare to make a decision. He forwarded my application to the top university management. They were supposed to decide.” Xi writes, “but this became my chance since Tsinghua University was caught in the vortex of a cultural-revolutionary political campaign against the so-called ‘right winds of restoration’ in July, August, and September 1975.” The two (ultra-leftist) university leaders, who he names as Chi Qun and Xie Chengyi, had no time to attend to newly admitted students, and so Xi, a farmer student, eluded their attention. He writes: “At this time my father had just come out of exile and was sent to work in a factory in Luoyang. This factory then turned to me in a letter to Tsinghua: ‘Comrade Xi Zhongxun’s problems are among the people’s contradictions. They should not prevent his children from studying or working.’ It was enough of a letter of recommendation for me to attend university.”

Xi studied chemistry. When he graduated in 1979, he was hired as a secretary by then defense minister and political bureau member Geng Biao (a friend of Xi’s now fully rehabilitated father). But at his own request, Xi transferred to the county seat of Zhengding in the province of Hebei in 1982 and started in the position of vice party secretary. He recounts that at the time, many did not understand why he was leaving Beijing. “Besides me, others went back to the lowest administrative level as well, Liu Yuan for example, (Son of Liu Shaoqi, the former state president persecuted to death by Mao). Independently, we both came to the same conclusion to join the workers and peasants.”

In fact, working in the provinces is a classic way to make a political career in the People’s Republic. Starting in 1982, Xi’s 25-year ascent began across four provinces until he reached the center of power in Beijing in 2007.

In his CV, written in 2003, at no point, Xi critically reflects on what happened to him, even as he admits to having been treated unfairly. He concludes that his seven years of experience in the countryside made him a “down-to-earth” man. He is “not prone to false doctrines,” is not shaken by anything, and will go any distance to “to get ahead.”

Today, at 12:00 PM CEST, the Olympic Games will start in Tokyo. Athletes are already preparing in their respective disciplines, like athlete Zeng Wenhui of the Chinese skateboarding team.