Container congestion at Chinese ports has been a major concern for European logistics companies for several months. Due to the lockdowns of Chinese coastal cities, more ships are once again awaiting processing, as Christiane Kuehl reports. Analysts already call these container ships floating warehouses. European port operators expect even more chaos in 2022 than in 2021. Because these disruptions also cause containers to pile up in Europe.

China’s social credit system also causes headaches for foreign companies in the country. Two years after its gradual introduction, many details of the system are still unclear. For example, environmental, customs and tax data are gathered, but no one knows if, or how they are interlinked. There is no uniform national system. German companies also fear data theft and their competitors, Marcel Grzanna reports.

Frustration is rising in China over Covid lockdowns. Anger at authorities for locking up hundreds of millions of people, food and medicine shortages. All this is being vented, especially on the Internet. And surprisingly, Beijing is letting some critical posts slip through the censor cracks, Johnny Erling writes in his column. Mockery and political jokes on social networks provide an outlet for people to blow off some steam.

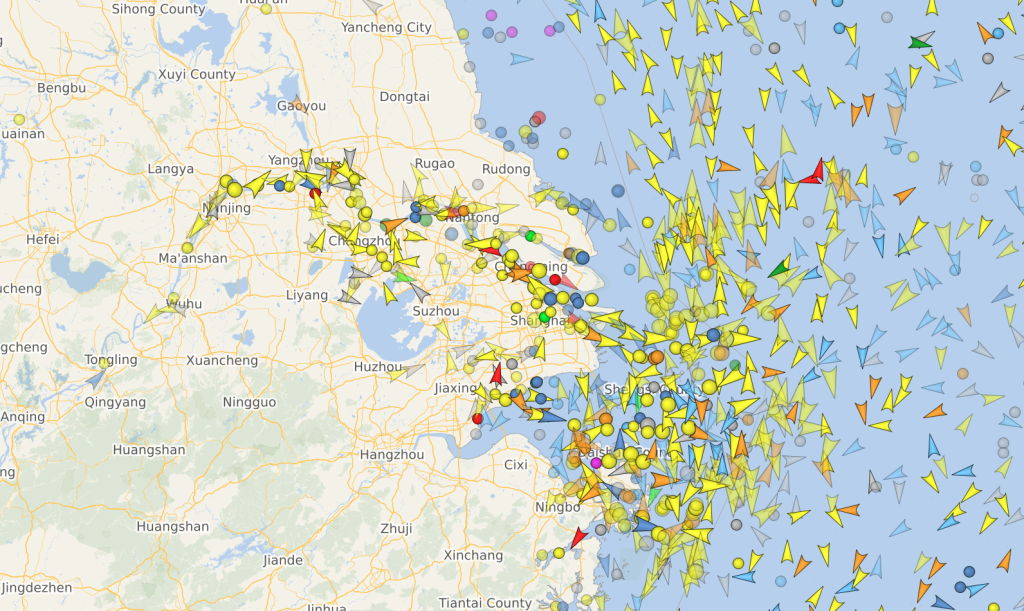

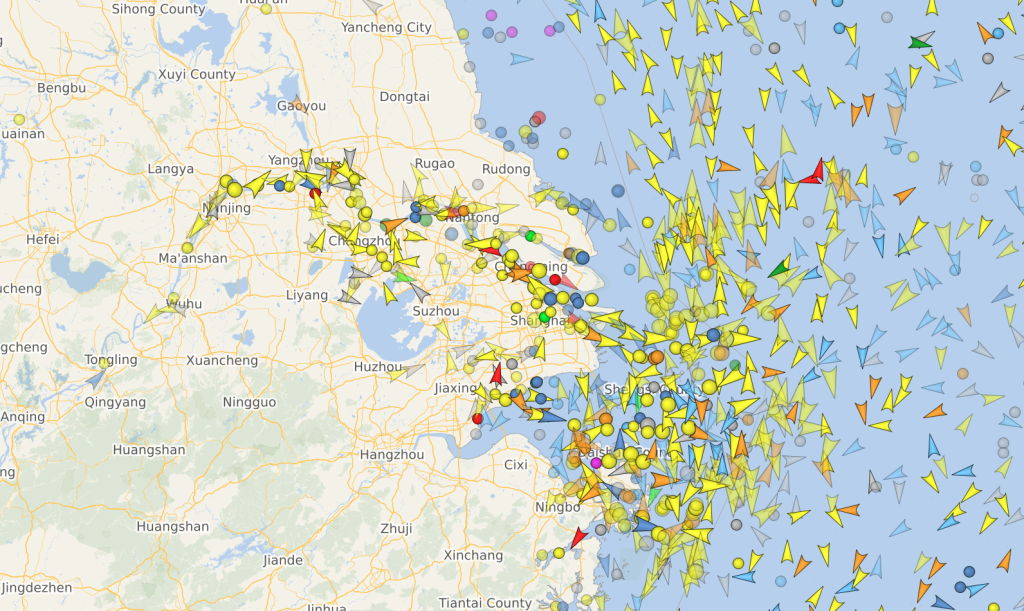

They’re back: The infamous cargo ship jams that have repeatedly disrupted global supply chains since the pandemic began have reappeared off China’s coasts. Last Wednesday, 230 ships anchored at the shared roadstead off the ports of Shanghai and Ningbo, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. On Thursday, ship tracking website Vesselfinder already classified 296 ships as “expected” off both Ningbo and Shanghai’s ports yesterday. Some are being diverted to Shenzhen, causing ships to pile up there as well.

Shanghai’s ports continue operations in a “closed-loop” system, but are isolated from the city (China.Table reported). Truck access is severely restricted. Containers currently wait an average of 12 days before being picked up via truck, according to Bloomberg. Perishable and hazardous goods are not handled at all. Conversely, export cargo does not enter the port at all.

Experts point to Shanghai’s enormous share in global goods traffic. The port processes numerous high-demand products. “Major export industries in the municipality include computer technology, automotive parts and semiconductors,” says Chris Rogers, researcher at digital freight forwarder Flexport. For computers and auto parts, Shanghai handles just over 10 percent of Chinese exports each. For semiconductors, Shanghai’s share is as high as nearly 20 percent. “Therefore, the bottleneck is a serious problem for exporters of all these goods.” The US and Europe are starting to see shortages, Rogers told China.Table. “Goods that people need are stuck on ships that are already being called ‘floating warehouses.’” From Asia to Europe, a ship now takes about 120 days instead of the usual 50.

Overall, there is a container capacity of around 25 million standard containers (TEU) worldwide, explains Philip Oetker, Chief Commercial Officer of shipping company Hamburg Sued. Of this capacity, a decreasing proportion is actually on the move on the seas, Oetker said on Thursday at a webinar of the German Chamber of Foreign Trade (AHK) in Hong Kong in cooperation with China.Table. In January 2020, around 19 million standard containers (TEU) were still in active use on ships. Today, there are only 16.5 million TEUs, Oetker said, citing a McKinsey study.

The reasons for the traffic chaos at sea, which has now lasted for more than two years, are not only the Covid pandemic but also other extraordinary effects such as the grounding of the “Ever Given”. Now, the war in Ukraine diverts commodity flows and drives up costs – and not just for raw materials, which are no longer sourced from Russia. But also for the logistics sector, according to Axel Mattern, Managing Director of the Port of Hamburg – for example, through longer distances and travel times. Coal, for example, is no longer transported to Hamburg from Russia, but from Australia, Mattern said at the AHK webinar.

In any case, the role of the Covid pandemic in the situation is substantial. China accounts for about twelve percent of global trade, so the problems created by its zero-covid policy affect the entire world. Some of these are caused by additional effects, such as the Covid stimulus package from the US in 2021: This caused local demand for goods to explode, many of which come from China. However, due to cargo congestion off China’s coasts, many of the containers arriving in the US cannot return to the People’s Republic at the usual rate – neither empty, nor filled with export goods. Terminals are overflowing with containers, as is the case in Europe. There, the chaos is amplified by the proximity to the war in Ukraine. Rotterdam, Hamburg, Antwerp, and three ports in the United Kingdom are at or over capacity.

Ports are feeling the consequences. “Containers currently wait 60 percent longer than they normally would,” Thomas Luetje, Sales Director at Hamburg terminal operator HHLA, said at the webinar. “We have limited space, because terminals are designed to handle containers, not to store them.” Currently, Luetje said, six ships are waiting to dock at HHLA. “I’ve never experienced this before.”

It does not seem like the situation would end anytime soon. “We expect a bigger mess than last year,” Jacques Vandermeiren, CEO of the Port of Antwerp, with Europe’s second-largest container volume, said in a recent interview. “It will have a negative impact – and a big negative impact – for the whole of 2022.”

Still, overseas buyers’ expectations have been changing since early 2022, reported Sunny Ho, Director of the Hong Kong Shippers Council, at the webinar. Buyers “see Covid as almost over. While they accepted logistics operational disruptions from 2020 to 2022, today they’re saying, ‘That’s your problem, not mine.’” Buyers, for example, are now demanding again that the carrier pays for air freight if the ship is not on time. “That wasn’t the case before. And yet we have been suffering from disruptions in Shenzhen and Hong Kong for nine months, with some 400 shipments canceled. And it’s not just the lockdown itself. The consequences will be felt for a long time.”

The situation accelerates the trend toward supply chain diversification, Ho says. “Overseas buyers are asking Hong Kong suppliers to diversify their sources.”

You can only adapt so much to geopolitical risks, says Luetje from HHLA. “But one thing is clear: all logistics operators are in the same boat.” This includes freight forwarders, shipping companies, and ports and terminals in the shipping industry. In the future, there needs to be better cooperation than before, says Luetje. In October, HHLA sold 35 percent of its Tollerort terminal to the terminal division of Chinese state shipping company COSCO and has high hopes for goods traffic with China (China.Table reported).

Oetker of Hamburg Sued, meanwhile, would prefer to see more attention paid to logistics than before the pandemic. “Marketing or finance were considered much more relevant than logistics. Managers should better understand the complex ecosystem of logistics and also the reasons for congestion.” Luetje also hopes to see more buffer time at companies, instead of the tightly timed just-in-time production that has been the norm. Perhaps, after the end of the current crisis, customers will finally listen to logisticians.

A lack of transparency, unclear responsibilities, and obscure evaluation criteria – numerous questions about the implementation of China’s social credit system for companies are still unanswered. In addition, companies fear denunciation, malpractice and new market hurdles. So far, companies have been searching in vain for answers to their questions.

A year ago, the German Chamber of Commerce in China (AHK) and representatives of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) already agreed to organize a workshop to reduce the risk of German companies being caught in the crossfire. However, the conference has yet to take place.

The delays can only partly be attributed to China’s covid policy. Competence disputes between the NDRC and other relevant agencies, like the Chinese central bank, take additional time and confuse all parties involved. The Reform Commission is indeed in charge. But because the system has a decisive influence on lending to companies, chief bankers do not take kindly to interference in their work.

It also is unclear what overarching assessments the numerous datasets will be used for. “Assigning a single social credit number to a company also enables entries from the environmental sector, quality inspection or the customs authority (China.Table reported). We know that this data is being collected. But it is not yet clear whether they will also be interlinked,” says Veronique Dunai from the China Competence Center of the Frankfurt and Darmstadt Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

IHK research shows that companies do not know how the algorithm will calculate the score. On Thursday, Dunai spoke at the event “China’s Social Credit System: How does it impact German companies?” from IfW Kiel’s Global China Conversations series.

Doris Fischer, Chair of China Business and Economics at the Julius-Maximilian University of Wurzburg, calls it a “hodgepodge”. There is still uncertainty about which criteria will be used, she says, and there are many regional differences. And the fact that a uniform national system has still not been created is an indicator that “there will continue to be adjustments in the future.”

Fischer argues that one goal of the social credit system is to replace, to some extent, the lack of reliable rule of law. Great mistrust between Chinese business partners is traditionally overcome by investing a great deal of social capital. In other words, a Chinese company invests a lot of money in restaurant and sauna visits with business partners to make sure they don’t end up with the wrong party. “The social credit system can build trust where building business relationships have cost time and money so far,” Fischer says. China’s legal system has not necessarily generated such trust in recent years.

But trust in the social credit system has to be built first. German companies are not yet convinced that the system is foolproof. Yet they are precisely the kind of companies that take great care to avoid any mistakes. They are well aware that, as foreign businessmen, they can quickly be caught in the crossfire in China. “Actually, the system is aimed at notorious rule-breakers, who are to be disciplined, and not at German companies. But they still have to keep in line,” says Fischer.

In practice, this means that companies fear that data and company secrets will be taken from them. They are worried about the consequences of customers complaining to the market supervisory authority – and perhaps unjustified. Or could the Chinese government unexpectedly set new requirements as part of the social credit system, without the need for a corresponding legal basis?

There are also still no clear details about its extraterritorial reach. For example, a business relationship between a parent company and Lithuanian partners could have consequences for the subsidiary in China. Following the dispute over an official Taiwanese representation in Lithuania’s capital Vilnius, Chinese authorities had already suspended the import of all goods from the Baltic EU state.

The lack of clear criteria also harbors risks in extraordinary situations. Companies that run into payment difficulties due to a lockdown or are unable to fulfill government contracts should not be devalued. Veronique Dunai recounts the case of a German company that received a formal warning and a note in the system over a five-dollar difference between the information on the company’s website and in its business license.

“As long as there is no uniform system, the human factor opens the door to arbitrariness,” says Doris Fischer of the University of Wuerzburg. At least in one case, however, a German company has already made a good experience, the IHK noted. In one specific case of non-compliance, a clear set of measures was specified before the entry could be deleted. Within 24 hours after resolving the complaint, the entry in the social credit system had disappeared.

The next event in the Global China Conversations series of the Kiel Institute China Initiative will be held on May 19. This time the topic will be “The Race for Technology Sovereignty: The Case of Government Support in the Semiconductor Industry” with speakers from BDI and OECD. China.Table is a media partner of the event series.

Operators and ports along the northern route of the new Silk Road report a 30 to 40 percent drop in cargo volume. Although trains are running, explains Maria Leenen of consulting firm SCI Verkehr. “But customers of high-value container cargo are worried about the safety of their cargo.”

This primarily concerns shipments from China to Europe, because most commodity flows via train along the Silk Road only go in this direction. To maintain or even expand the flow of goods to the west, Chinese operators offer financial guarantees. In March 2022, a Xian-based operator began taking war insurance payments for logistic companies, Leene reports. They apply to all Russian and European destinations.

“War insurance policies are purchased for goods transported through Russia, Belarus and Poland, which are neighboring countries of Ukraine.” These policies are intended to protect against the increased risk of damage or seizure due to military operations, according to the business consultant. While the insurance is not mandatory, it is said to serve as an incentive to move goods between China and the EU.

The European side is hardly affected by the war and sanctions against Russia. The German logistics sector does not consider itself to be particularly economically affected. “Even though the cost situation has worsened due to exorbitant increases in energy prices, we have managed to pass most of these costs on to the market,” says Niels Beuck, Director and Head of Rail Logistics at the German Federal Association for Freight Forwarding and Logistics (DSLV). In other words, the costs are passed on to the customers. Because in order to protect their procurement channels and supply chains, industry and trade would currently accept price jumps in freight rates for all modes of transport. In any case, logistics companies currently work at full capacity due to the high demand for freight transport, says Beuck.

DB Cargo, one of Europe’s largest transport companies, also plays down the impact of the war on the sector. The company is “just one player of many” along the route, a company spokesman told Table.Media. It does not operate trains in Russia. Furthermore, bookings by European companies for shipments via Russia – even though they are carried out by the Russian state railroad RZD – are not affected by sanctions. Only financial transactions, like the purchase of RZD shares, are prohibited. Thus, only European exports with Russian destinations are canceled. For example, components for the automotive industry are no longer supplied to Russian plants, as sanctions apply here.

However, this is not significant, as borders are still crossed along the Silk Road. Still, preparations seem to be underway to bypass the northern Russia route. The so-called middle corridor via Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey is currently being developed at full speed, according to the DSLV. However, the ferries on the Caspian Sea are a limiting factor of the middle corridor. “Starting in September, ferry capacity is to be doubled, from three departures to six,” says Director Beuck.

The transport time on this route is 28 days, according to Dutch logistics service provider Nunner Logistics, which set up the middle corridor together with Chinese logistics company Tiedada and Duisport, the Port of Duisburg operator. On the northern route, containers are on the move for about 14 days. This means that the capacity increase of the middle corridor cannot fully compensate for a possible shutdown of the northern route. According to Beuck, however, it is one of several pieces of the puzzle to bypass transport through Russia. “Besides, the same volumes as currently can’t be handled ad hoc via the new route,” says management consultant Maria Leenen.

So the rail route via Russia will remain vital for goods traffic between China and the EU. Air transport is not an alternative in most cases due to the largely closed-off Russian airspace, significantly higher costs and the poor CO2 balance. The harsh Covid lockdown in the Chinese metropolis of Shanghai, the world’s largest container port, makes a backup solution even more important. Rail transport offers another advantage here: Shiploads via Shanghai have to be loaded onto trains in both directions to get from the point of origin to the port or from the port to the destination. This additional step is no longer necessary and goods can be loaded or unloaded in Central China, where many goods are produced.

Pony.ai and Baidu are allowed to operate additional self-driving cabs in Beijing since Thursday. Authorities have given the green light for this, as reported by the Financial Times. However, there has to be a driver present in the car who can take action in case of an emergency. The 14 newly registered cars will be allowed to operate in a 60-square-kilometer zone in the Yizhuang district. The two companies had previously conducted a five-month pilot program, according to business portal Caixin. In approving these so-called robo-taxis, Beijing follows smaller Chinese cities.

Pony.ai, which is supported by Toyota, had already been granted a license to operate autonomous cabs in Guangzhou last week. Starting in May, 100 cars are scheduled to hit the streets – but also with a driver behind the wheel in Guangzhou. In California, Pony.ai lost its license for tests without human drivers after six months. A self-driving car had crashed into a traffic sign while changing lanes.

According to one analyst, the successful commercialization of self-driving cabs is still a long way off. Transporting passengers by driverless companies currently costs more money than by normal cabs and ride-hailing services. nib

Short message service Weibo plans to publish the location of its users in the future. According to a post by the company, the goal is to “reduce malicious disinformation and automated theft of web content, and ensure the authenticity and transparency of distributed content.”

Weibo explained the move by stating that it has “always been committed to maintaining a healthy and orderly atmosphere of discussion and protecting the rights and interests of users to quickly obtain real and effective information.” Last month, other platforms such as news site Jinri Toutiao, video portals Douyin and Kuaishou, and lifestyle platform Xiaohongshu had already begun to display the locations of their users. Experts see this as a signal that the sentiment on social networks is to be brought into line with the Party. Last year, Beijing had taken increased action with harsh fines against large tech companies and their social media platforms. Above all, the entertainment industry was supposed to be brought under control (China.Table reported).

Last month, Weibo announced the introduction of an IP location feature following an increase in disinformation on the platform in connection with the Russia-Ukraine war.

Weibo counts more than 570 million monthly active users. Effective immediately, according to Thursday’s announcement, the IP address of users will be displayed on their profile and when they post comments, and can no longer be disabled. For Weibo users in China, the province or municipality will be displayed as their location. For overseas users, the country of the IP address will be displayed. niw

China will fully cut tariffs on coal imports. This was announced by the Ministry of Finance on Thursday. The tariff cuts will be effective from the beginning of May until the end of March 2023. The measure is intended to ensure the country’s energy security. Previously, tariffs against some trading partners were three to six percent.

China’s coal imports were down 24 percent in March. However, whether the measure will have much effect is doubtful. The majority of China’s coal supply originates from domestic sources. Only eight percent of coal consumption is imported, Reuters reported. Tariff rates for key suppliers such as Indonesia have already been set at zero percent in the past, Bloomberg reports. However, the tariff rate for coal imports from Russia was previously six percent. Coal traders believe that imports from Russia will benefit from the tariff cut.

Last year, power plant operators failed to build up sufficient stocks due to high coal prices. This led to a power crisis in the fall, which kept industrial plants on edge for weeks and resulted in power rationing. Subsequently, domestic coal production was expanded, and electricity rates were adjusted to ensure that power plants remain profitable even when coal prices are high.

Authorities had recently ordered local coal industries to increase production capacity by 300 million tons this year (China.Table reported). However, an industry association close to the government doubts that this target can be met. China could realize only 100 million metric tons of new capacity this year, an analyst at China Coal Transportation and Distribution Association said recently. This was due to safety and environmental regulations. The expansion of coal production since the end of last year has already led to an increase in the number of coal miners killed in accidents in the mines throughout the People’s Republic. nib

A major court case against 47 Hong Kong democracy activists has been postponed until early June. Authorities announced on Thursday. The activists have been charged under the National Security Law. Many of the defendants have been in pre-trial custody since February last year, according to Reuters. They include, for example, well-known activist Joshua Wong. Only 13 of the activists have been released on bail.

All 47 individuals were arrested on charges of “conspiracy to subvert”. They had participated in an unofficial, non-binding and independently organized primary election in 2020 to select candidates for the now postponed local elections.

High Court Judge Esther Toh said in a statement on Tuesday that procedural developments in the case indicate “there will be a long delay to trial.” The National Security Law was placed on Hong Kong by China in 2020. nib

China’s leadership responds to the high infection risk of the Omicron variant with radical lockdowns of public life. As was once the case in Wuhan, one in four Chinese – more than 350 million people to date – were forced to isolate themselves and have been locked in for varying lengths of time in dozens of cities since the spring. Only thanks to the Internet have those affected so far been able to provide themselves with food and essential goods – albeit with varying degrees of success. At the same time, they are using the new virtual reality to openly voice their frustration.

One example: Superstitious Beijingers immediately thought of a bad omen on March 4, some even hoped for it. A day before the opening of the annual parliamentary session of the People’s Congress, news of a strange incident spread online. At the Taihedian (太和殿), the Hall of Supreme Harmony in the Imperial Palace, once the seat of imperial power, the entrance gate had toppled. A whirlwind was said to have crushed the massive gateway. Shaky cell phone footage showed the huge wooden gate lying on the ground.

For some, it was a time-honored sign when China’s rulers had been stripped of their Mandate of Heaven and a change of dynasty was on the horizon. Party leader Xi Jinping, while not directly named in many online posts about the incident, is crudely mentioned by his nickname, “dumpling” (包子).

It was one of the many rumors (谣言) currently playing a cat and mouse game with censors on China’s Internet. Many bloggers use clever puns to make political jokes. It was the same with the fallen gate. Time and again, bloggers mock the People’s Congress deputies as compliant sloganeers who “make a lot of wind” (吹风) to please the Chinese leadership. As thousands of delegates gathered in Beijing on March 4, their collective huffing might have even brought down the mighty imperial palace portal.

It does not matter whether the gate really fell over. The video clips look faked; Beijing did not experience any abnormal weather phenomena that day. The news was probably fake news (假新闻). But it was the perfect opportunity to vent widespread frustration about current conditions in lockdown cities.

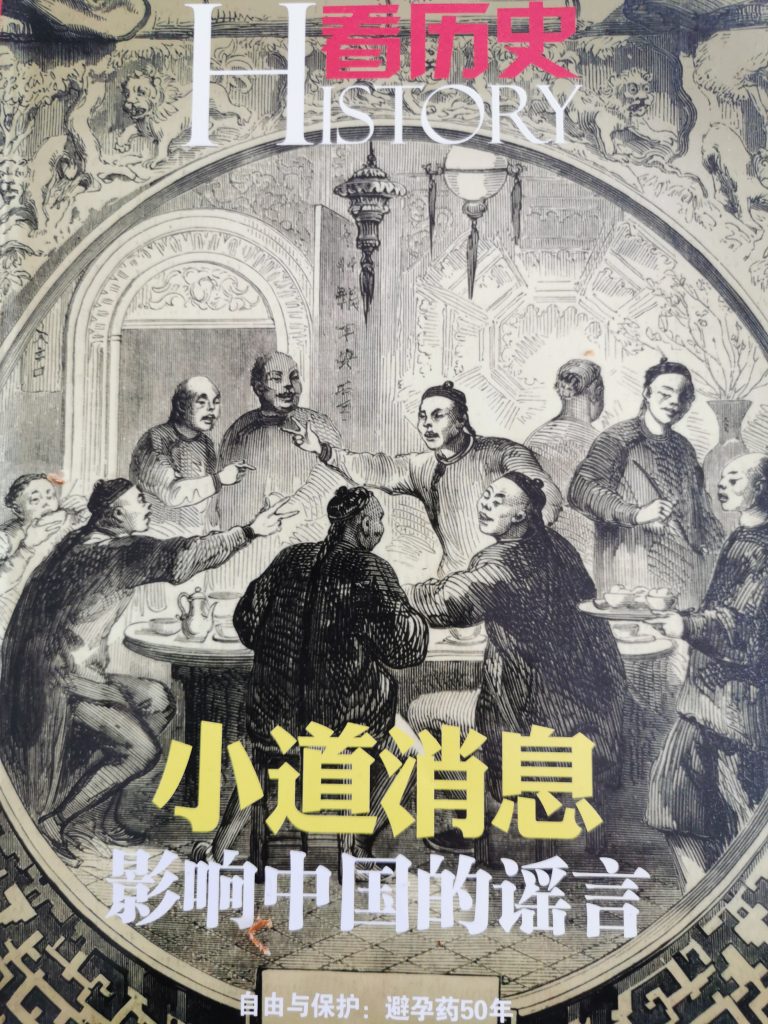

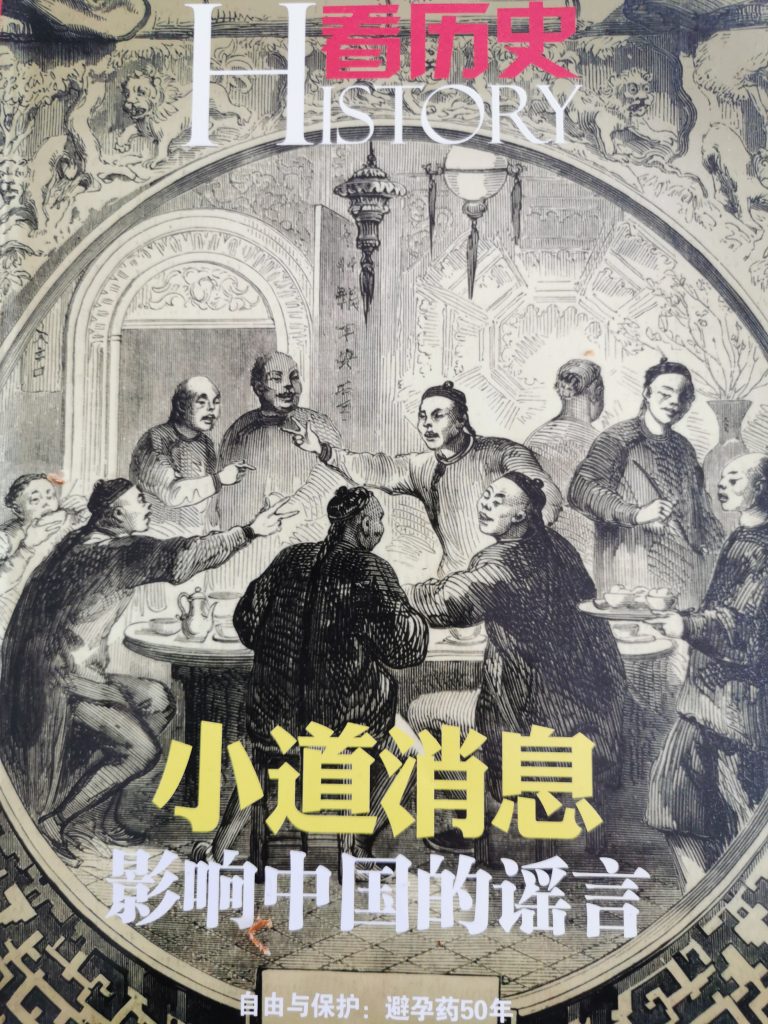

In China’s despot-ruled unfree society, clandestine political gossip once had its own term, the Xiaodao Xiaoxi (小道消息), which literally means “news that goes through the little way.” Scholars and merchants met in their courts and whispered about scandalous events in public life or at the imperial court. In 2010, the prestigious Chinese magazine History (看历史) published a special issue on how the Xiaodao Xiaoxi grew into explosive rumors and influenced political developments – both for feudal rulers and later for Mao’s Communists after the founding of the People’s Republic (小道消息:影响中国的谣言).

For instance, in the spring of 1891, people in eastern China’s Yangzhou city spread outrageous rumors that Christian missionaries were murdering Chinese infants to extract medicine or silver from their eyes. This led to a “holy war” against missionaries, foreigners and Chinese Christians. In the past, followers of Confucian teachings had already campaigned against them with pseudo-religious delusions. Pamphlets demonized the Jesuits around Matteo Ricci as alchemists who allegedly killed Chinese for this purpose.

Rumors could destroy political stability when social contradictions in society were severe. Only open information could have defused them, the magazine concludes. This remains unchanged today, when rumors, fake news and jokes are an expression of a deep-seated resentment of conditions.

Beijing takes this so seriously that it responded not only with the usual harsh suppression and expansion of censorship. In addition to COVID-19, China had to be wary of the danger of a “secondary epidemic” spread via rumors. Party leader Xi already ordered the creation of the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission (中央网络安全和信息化委员会) on August 29, 2018, to correct (alleged) rumors (辟谣平台). According to their website, more than 30,000 rumors have been reported to date, of which 9,000 have been red-stamped “false report”.

The Party and the state decide what is fake news or what is a rumor. But increasingly absurd conspiracy theories (阴谋论) are emanating not from bloggers, but from Party agencies like the Foreign Ministry. There, Foreign Office spokesman Zhao Lijian made a name for himself as a “wolf warrior” after he blamed the US for the Covid outbreak and even accused Washington of being involved in alleged biochemical weapons manufacturing experiments in Ukraine. Zhao pushed it so far – despite his appeals to patriotism – that Chinese bloggers have made him a target of their own scorn.

The web is filled with all forms of allusions to the party’s poor pandemic control. One blogger put a snail on a razor blade in a photo montage and wrote underneath: “It can’t go forward, it can’t go back. Standing still is not an option.”

Another blogger showed creativity by transforming the famous skyscraper silhouette of Pudong into a vegetable arrangement as his reproach to the authorities for failing to provide enough food for Shanghai’s citizens during the lockdown.

These political jokes are virtual slaps in the face to Xi, who constantly praises himself, the Party and his superior socialist system for how exemplary they have been in fighting the pandemic compared to the chaos in the West.

Bloggers are fighting back with jokes. In recent days, online collections of political jokes have appeared daily in Beijing under the heading “Beijing punchlines from yesterday.” (昨天北京人的段子). This is where, as long as Beijing’s residents can still go grocery shopping, survival lists for food are shared and what can be learned from the experience of the once hoity-toity Shanghainese who got blindsided by the lockdown: “Beijingers: buy freezers, so you’ll have a second fridge just in case.”

I witnessed similar virtual mass reactions like those currently happening in Shanghai and Beijing back in 2003. At the time, China’s leadership first denied the then predecessor disease SARS and then had it covered up, as it did in Wuhan in 2020. Only when there was no other way, Beijing mobilized the whole country to fight SARS.

At the time, the population was beside itself with anger on the Internet. The party initially tolerated their virtual criticism, used it as an outlet for emotions, and punished some higher officials. After a few months, everything was forgotten. China’s CP now turned the tables, declared itself the winner and settled accounts with activists.

Virtual mass anger and solidarity with the victims have erupted again and again over the past two years. Online outbursts of emotion “never last long. Nor do they lead to acts of resistance in China’s real world,” writes China expert James Palmer, editor of China Policy Brief: “Bloggers are taking a mild risk with their online postings. Real-world protests, however, have become even more dangerous under Xi’s rule.”

At the very least, the mass discontent on the Internet triggered by the lockdowns reveals the true mood of the people. If there were free elections and uncensored media in China, Xi would have a thing coming.

David Chin resigns as head of UBS China. He is the third executive of a global bank in China to step down this month, Bloomberg reports. Chin will be succeeded by Eugene Qian, Chairman of UBS Securities, after two years in the post.

Wanderlust? Someday, the Covid pandemic will end. Then, the Zhangjiajie Stone Pillars near Wulingyuan in Hunan Province could be a worthwhile visit. It has been a Unesco World Natural Heritage Site since 1992.

Container congestion at Chinese ports has been a major concern for European logistics companies for several months. Due to the lockdowns of Chinese coastal cities, more ships are once again awaiting processing, as Christiane Kuehl reports. Analysts already call these container ships floating warehouses. European port operators expect even more chaos in 2022 than in 2021. Because these disruptions also cause containers to pile up in Europe.

China’s social credit system also causes headaches for foreign companies in the country. Two years after its gradual introduction, many details of the system are still unclear. For example, environmental, customs and tax data are gathered, but no one knows if, or how they are interlinked. There is no uniform national system. German companies also fear data theft and their competitors, Marcel Grzanna reports.

Frustration is rising in China over Covid lockdowns. Anger at authorities for locking up hundreds of millions of people, food and medicine shortages. All this is being vented, especially on the Internet. And surprisingly, Beijing is letting some critical posts slip through the censor cracks, Johnny Erling writes in his column. Mockery and political jokes on social networks provide an outlet for people to blow off some steam.

They’re back: The infamous cargo ship jams that have repeatedly disrupted global supply chains since the pandemic began have reappeared off China’s coasts. Last Wednesday, 230 ships anchored at the shared roadstead off the ports of Shanghai and Ningbo, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. On Thursday, ship tracking website Vesselfinder already classified 296 ships as “expected” off both Ningbo and Shanghai’s ports yesterday. Some are being diverted to Shenzhen, causing ships to pile up there as well.

Shanghai’s ports continue operations in a “closed-loop” system, but are isolated from the city (China.Table reported). Truck access is severely restricted. Containers currently wait an average of 12 days before being picked up via truck, according to Bloomberg. Perishable and hazardous goods are not handled at all. Conversely, export cargo does not enter the port at all.

Experts point to Shanghai’s enormous share in global goods traffic. The port processes numerous high-demand products. “Major export industries in the municipality include computer technology, automotive parts and semiconductors,” says Chris Rogers, researcher at digital freight forwarder Flexport. For computers and auto parts, Shanghai handles just over 10 percent of Chinese exports each. For semiconductors, Shanghai’s share is as high as nearly 20 percent. “Therefore, the bottleneck is a serious problem for exporters of all these goods.” The US and Europe are starting to see shortages, Rogers told China.Table. “Goods that people need are stuck on ships that are already being called ‘floating warehouses.’” From Asia to Europe, a ship now takes about 120 days instead of the usual 50.

Overall, there is a container capacity of around 25 million standard containers (TEU) worldwide, explains Philip Oetker, Chief Commercial Officer of shipping company Hamburg Sued. Of this capacity, a decreasing proportion is actually on the move on the seas, Oetker said on Thursday at a webinar of the German Chamber of Foreign Trade (AHK) in Hong Kong in cooperation with China.Table. In January 2020, around 19 million standard containers (TEU) were still in active use on ships. Today, there are only 16.5 million TEUs, Oetker said, citing a McKinsey study.

The reasons for the traffic chaos at sea, which has now lasted for more than two years, are not only the Covid pandemic but also other extraordinary effects such as the grounding of the “Ever Given”. Now, the war in Ukraine diverts commodity flows and drives up costs – and not just for raw materials, which are no longer sourced from Russia. But also for the logistics sector, according to Axel Mattern, Managing Director of the Port of Hamburg – for example, through longer distances and travel times. Coal, for example, is no longer transported to Hamburg from Russia, but from Australia, Mattern said at the AHK webinar.

In any case, the role of the Covid pandemic in the situation is substantial. China accounts for about twelve percent of global trade, so the problems created by its zero-covid policy affect the entire world. Some of these are caused by additional effects, such as the Covid stimulus package from the US in 2021: This caused local demand for goods to explode, many of which come from China. However, due to cargo congestion off China’s coasts, many of the containers arriving in the US cannot return to the People’s Republic at the usual rate – neither empty, nor filled with export goods. Terminals are overflowing with containers, as is the case in Europe. There, the chaos is amplified by the proximity to the war in Ukraine. Rotterdam, Hamburg, Antwerp, and three ports in the United Kingdom are at or over capacity.

Ports are feeling the consequences. “Containers currently wait 60 percent longer than they normally would,” Thomas Luetje, Sales Director at Hamburg terminal operator HHLA, said at the webinar. “We have limited space, because terminals are designed to handle containers, not to store them.” Currently, Luetje said, six ships are waiting to dock at HHLA. “I’ve never experienced this before.”

It does not seem like the situation would end anytime soon. “We expect a bigger mess than last year,” Jacques Vandermeiren, CEO of the Port of Antwerp, with Europe’s second-largest container volume, said in a recent interview. “It will have a negative impact – and a big negative impact – for the whole of 2022.”

Still, overseas buyers’ expectations have been changing since early 2022, reported Sunny Ho, Director of the Hong Kong Shippers Council, at the webinar. Buyers “see Covid as almost over. While they accepted logistics operational disruptions from 2020 to 2022, today they’re saying, ‘That’s your problem, not mine.’” Buyers, for example, are now demanding again that the carrier pays for air freight if the ship is not on time. “That wasn’t the case before. And yet we have been suffering from disruptions in Shenzhen and Hong Kong for nine months, with some 400 shipments canceled. And it’s not just the lockdown itself. The consequences will be felt for a long time.”

The situation accelerates the trend toward supply chain diversification, Ho says. “Overseas buyers are asking Hong Kong suppliers to diversify their sources.”

You can only adapt so much to geopolitical risks, says Luetje from HHLA. “But one thing is clear: all logistics operators are in the same boat.” This includes freight forwarders, shipping companies, and ports and terminals in the shipping industry. In the future, there needs to be better cooperation than before, says Luetje. In October, HHLA sold 35 percent of its Tollerort terminal to the terminal division of Chinese state shipping company COSCO and has high hopes for goods traffic with China (China.Table reported).

Oetker of Hamburg Sued, meanwhile, would prefer to see more attention paid to logistics than before the pandemic. “Marketing or finance were considered much more relevant than logistics. Managers should better understand the complex ecosystem of logistics and also the reasons for congestion.” Luetje also hopes to see more buffer time at companies, instead of the tightly timed just-in-time production that has been the norm. Perhaps, after the end of the current crisis, customers will finally listen to logisticians.

A lack of transparency, unclear responsibilities, and obscure evaluation criteria – numerous questions about the implementation of China’s social credit system for companies are still unanswered. In addition, companies fear denunciation, malpractice and new market hurdles. So far, companies have been searching in vain for answers to their questions.

A year ago, the German Chamber of Commerce in China (AHK) and representatives of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) already agreed to organize a workshop to reduce the risk of German companies being caught in the crossfire. However, the conference has yet to take place.

The delays can only partly be attributed to China’s covid policy. Competence disputes between the NDRC and other relevant agencies, like the Chinese central bank, take additional time and confuse all parties involved. The Reform Commission is indeed in charge. But because the system has a decisive influence on lending to companies, chief bankers do not take kindly to interference in their work.

It also is unclear what overarching assessments the numerous datasets will be used for. “Assigning a single social credit number to a company also enables entries from the environmental sector, quality inspection or the customs authority (China.Table reported). We know that this data is being collected. But it is not yet clear whether they will also be interlinked,” says Veronique Dunai from the China Competence Center of the Frankfurt and Darmstadt Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

IHK research shows that companies do not know how the algorithm will calculate the score. On Thursday, Dunai spoke at the event “China’s Social Credit System: How does it impact German companies?” from IfW Kiel’s Global China Conversations series.

Doris Fischer, Chair of China Business and Economics at the Julius-Maximilian University of Wurzburg, calls it a “hodgepodge”. There is still uncertainty about which criteria will be used, she says, and there are many regional differences. And the fact that a uniform national system has still not been created is an indicator that “there will continue to be adjustments in the future.”

Fischer argues that one goal of the social credit system is to replace, to some extent, the lack of reliable rule of law. Great mistrust between Chinese business partners is traditionally overcome by investing a great deal of social capital. In other words, a Chinese company invests a lot of money in restaurant and sauna visits with business partners to make sure they don’t end up with the wrong party. “The social credit system can build trust where building business relationships have cost time and money so far,” Fischer says. China’s legal system has not necessarily generated such trust in recent years.

But trust in the social credit system has to be built first. German companies are not yet convinced that the system is foolproof. Yet they are precisely the kind of companies that take great care to avoid any mistakes. They are well aware that, as foreign businessmen, they can quickly be caught in the crossfire in China. “Actually, the system is aimed at notorious rule-breakers, who are to be disciplined, and not at German companies. But they still have to keep in line,” says Fischer.

In practice, this means that companies fear that data and company secrets will be taken from them. They are worried about the consequences of customers complaining to the market supervisory authority – and perhaps unjustified. Or could the Chinese government unexpectedly set new requirements as part of the social credit system, without the need for a corresponding legal basis?

There are also still no clear details about its extraterritorial reach. For example, a business relationship between a parent company and Lithuanian partners could have consequences for the subsidiary in China. Following the dispute over an official Taiwanese representation in Lithuania’s capital Vilnius, Chinese authorities had already suspended the import of all goods from the Baltic EU state.

The lack of clear criteria also harbors risks in extraordinary situations. Companies that run into payment difficulties due to a lockdown or are unable to fulfill government contracts should not be devalued. Veronique Dunai recounts the case of a German company that received a formal warning and a note in the system over a five-dollar difference between the information on the company’s website and in its business license.

“As long as there is no uniform system, the human factor opens the door to arbitrariness,” says Doris Fischer of the University of Wuerzburg. At least in one case, however, a German company has already made a good experience, the IHK noted. In one specific case of non-compliance, a clear set of measures was specified before the entry could be deleted. Within 24 hours after resolving the complaint, the entry in the social credit system had disappeared.

The next event in the Global China Conversations series of the Kiel Institute China Initiative will be held on May 19. This time the topic will be “The Race for Technology Sovereignty: The Case of Government Support in the Semiconductor Industry” with speakers from BDI and OECD. China.Table is a media partner of the event series.

Operators and ports along the northern route of the new Silk Road report a 30 to 40 percent drop in cargo volume. Although trains are running, explains Maria Leenen of consulting firm SCI Verkehr. “But customers of high-value container cargo are worried about the safety of their cargo.”

This primarily concerns shipments from China to Europe, because most commodity flows via train along the Silk Road only go in this direction. To maintain or even expand the flow of goods to the west, Chinese operators offer financial guarantees. In March 2022, a Xian-based operator began taking war insurance payments for logistic companies, Leene reports. They apply to all Russian and European destinations.

“War insurance policies are purchased for goods transported through Russia, Belarus and Poland, which are neighboring countries of Ukraine.” These policies are intended to protect against the increased risk of damage or seizure due to military operations, according to the business consultant. While the insurance is not mandatory, it is said to serve as an incentive to move goods between China and the EU.

The European side is hardly affected by the war and sanctions against Russia. The German logistics sector does not consider itself to be particularly economically affected. “Even though the cost situation has worsened due to exorbitant increases in energy prices, we have managed to pass most of these costs on to the market,” says Niels Beuck, Director and Head of Rail Logistics at the German Federal Association for Freight Forwarding and Logistics (DSLV). In other words, the costs are passed on to the customers. Because in order to protect their procurement channels and supply chains, industry and trade would currently accept price jumps in freight rates for all modes of transport. In any case, logistics companies currently work at full capacity due to the high demand for freight transport, says Beuck.

DB Cargo, one of Europe’s largest transport companies, also plays down the impact of the war on the sector. The company is “just one player of many” along the route, a company spokesman told Table.Media. It does not operate trains in Russia. Furthermore, bookings by European companies for shipments via Russia – even though they are carried out by the Russian state railroad RZD – are not affected by sanctions. Only financial transactions, like the purchase of RZD shares, are prohibited. Thus, only European exports with Russian destinations are canceled. For example, components for the automotive industry are no longer supplied to Russian plants, as sanctions apply here.

However, this is not significant, as borders are still crossed along the Silk Road. Still, preparations seem to be underway to bypass the northern Russia route. The so-called middle corridor via Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey is currently being developed at full speed, according to the DSLV. However, the ferries on the Caspian Sea are a limiting factor of the middle corridor. “Starting in September, ferry capacity is to be doubled, from three departures to six,” says Director Beuck.

The transport time on this route is 28 days, according to Dutch logistics service provider Nunner Logistics, which set up the middle corridor together with Chinese logistics company Tiedada and Duisport, the Port of Duisburg operator. On the northern route, containers are on the move for about 14 days. This means that the capacity increase of the middle corridor cannot fully compensate for a possible shutdown of the northern route. According to Beuck, however, it is one of several pieces of the puzzle to bypass transport through Russia. “Besides, the same volumes as currently can’t be handled ad hoc via the new route,” says management consultant Maria Leenen.

So the rail route via Russia will remain vital for goods traffic between China and the EU. Air transport is not an alternative in most cases due to the largely closed-off Russian airspace, significantly higher costs and the poor CO2 balance. The harsh Covid lockdown in the Chinese metropolis of Shanghai, the world’s largest container port, makes a backup solution even more important. Rail transport offers another advantage here: Shiploads via Shanghai have to be loaded onto trains in both directions to get from the point of origin to the port or from the port to the destination. This additional step is no longer necessary and goods can be loaded or unloaded in Central China, where many goods are produced.

Pony.ai and Baidu are allowed to operate additional self-driving cabs in Beijing since Thursday. Authorities have given the green light for this, as reported by the Financial Times. However, there has to be a driver present in the car who can take action in case of an emergency. The 14 newly registered cars will be allowed to operate in a 60-square-kilometer zone in the Yizhuang district. The two companies had previously conducted a five-month pilot program, according to business portal Caixin. In approving these so-called robo-taxis, Beijing follows smaller Chinese cities.

Pony.ai, which is supported by Toyota, had already been granted a license to operate autonomous cabs in Guangzhou last week. Starting in May, 100 cars are scheduled to hit the streets – but also with a driver behind the wheel in Guangzhou. In California, Pony.ai lost its license for tests without human drivers after six months. A self-driving car had crashed into a traffic sign while changing lanes.

According to one analyst, the successful commercialization of self-driving cabs is still a long way off. Transporting passengers by driverless companies currently costs more money than by normal cabs and ride-hailing services. nib

Short message service Weibo plans to publish the location of its users in the future. According to a post by the company, the goal is to “reduce malicious disinformation and automated theft of web content, and ensure the authenticity and transparency of distributed content.”

Weibo explained the move by stating that it has “always been committed to maintaining a healthy and orderly atmosphere of discussion and protecting the rights and interests of users to quickly obtain real and effective information.” Last month, other platforms such as news site Jinri Toutiao, video portals Douyin and Kuaishou, and lifestyle platform Xiaohongshu had already begun to display the locations of their users. Experts see this as a signal that the sentiment on social networks is to be brought into line with the Party. Last year, Beijing had taken increased action with harsh fines against large tech companies and their social media platforms. Above all, the entertainment industry was supposed to be brought under control (China.Table reported).

Last month, Weibo announced the introduction of an IP location feature following an increase in disinformation on the platform in connection with the Russia-Ukraine war.

Weibo counts more than 570 million monthly active users. Effective immediately, according to Thursday’s announcement, the IP address of users will be displayed on their profile and when they post comments, and can no longer be disabled. For Weibo users in China, the province or municipality will be displayed as their location. For overseas users, the country of the IP address will be displayed. niw

China will fully cut tariffs on coal imports. This was announced by the Ministry of Finance on Thursday. The tariff cuts will be effective from the beginning of May until the end of March 2023. The measure is intended to ensure the country’s energy security. Previously, tariffs against some trading partners were three to six percent.

China’s coal imports were down 24 percent in March. However, whether the measure will have much effect is doubtful. The majority of China’s coal supply originates from domestic sources. Only eight percent of coal consumption is imported, Reuters reported. Tariff rates for key suppliers such as Indonesia have already been set at zero percent in the past, Bloomberg reports. However, the tariff rate for coal imports from Russia was previously six percent. Coal traders believe that imports from Russia will benefit from the tariff cut.

Last year, power plant operators failed to build up sufficient stocks due to high coal prices. This led to a power crisis in the fall, which kept industrial plants on edge for weeks and resulted in power rationing. Subsequently, domestic coal production was expanded, and electricity rates were adjusted to ensure that power plants remain profitable even when coal prices are high.

Authorities had recently ordered local coal industries to increase production capacity by 300 million tons this year (China.Table reported). However, an industry association close to the government doubts that this target can be met. China could realize only 100 million metric tons of new capacity this year, an analyst at China Coal Transportation and Distribution Association said recently. This was due to safety and environmental regulations. The expansion of coal production since the end of last year has already led to an increase in the number of coal miners killed in accidents in the mines throughout the People’s Republic. nib

A major court case against 47 Hong Kong democracy activists has been postponed until early June. Authorities announced on Thursday. The activists have been charged under the National Security Law. Many of the defendants have been in pre-trial custody since February last year, according to Reuters. They include, for example, well-known activist Joshua Wong. Only 13 of the activists have been released on bail.

All 47 individuals were arrested on charges of “conspiracy to subvert”. They had participated in an unofficial, non-binding and independently organized primary election in 2020 to select candidates for the now postponed local elections.

High Court Judge Esther Toh said in a statement on Tuesday that procedural developments in the case indicate “there will be a long delay to trial.” The National Security Law was placed on Hong Kong by China in 2020. nib

China’s leadership responds to the high infection risk of the Omicron variant with radical lockdowns of public life. As was once the case in Wuhan, one in four Chinese – more than 350 million people to date – were forced to isolate themselves and have been locked in for varying lengths of time in dozens of cities since the spring. Only thanks to the Internet have those affected so far been able to provide themselves with food and essential goods – albeit with varying degrees of success. At the same time, they are using the new virtual reality to openly voice their frustration.

One example: Superstitious Beijingers immediately thought of a bad omen on March 4, some even hoped for it. A day before the opening of the annual parliamentary session of the People’s Congress, news of a strange incident spread online. At the Taihedian (太和殿), the Hall of Supreme Harmony in the Imperial Palace, once the seat of imperial power, the entrance gate had toppled. A whirlwind was said to have crushed the massive gateway. Shaky cell phone footage showed the huge wooden gate lying on the ground.

For some, it was a time-honored sign when China’s rulers had been stripped of their Mandate of Heaven and a change of dynasty was on the horizon. Party leader Xi Jinping, while not directly named in many online posts about the incident, is crudely mentioned by his nickname, “dumpling” (包子).

It was one of the many rumors (谣言) currently playing a cat and mouse game with censors on China’s Internet. Many bloggers use clever puns to make political jokes. It was the same with the fallen gate. Time and again, bloggers mock the People’s Congress deputies as compliant sloganeers who “make a lot of wind” (吹风) to please the Chinese leadership. As thousands of delegates gathered in Beijing on March 4, their collective huffing might have even brought down the mighty imperial palace portal.

It does not matter whether the gate really fell over. The video clips look faked; Beijing did not experience any abnormal weather phenomena that day. The news was probably fake news (假新闻). But it was the perfect opportunity to vent widespread frustration about current conditions in lockdown cities.

In China’s despot-ruled unfree society, clandestine political gossip once had its own term, the Xiaodao Xiaoxi (小道消息), which literally means “news that goes through the little way.” Scholars and merchants met in their courts and whispered about scandalous events in public life or at the imperial court. In 2010, the prestigious Chinese magazine History (看历史) published a special issue on how the Xiaodao Xiaoxi grew into explosive rumors and influenced political developments – both for feudal rulers and later for Mao’s Communists after the founding of the People’s Republic (小道消息:影响中国的谣言).

For instance, in the spring of 1891, people in eastern China’s Yangzhou city spread outrageous rumors that Christian missionaries were murdering Chinese infants to extract medicine or silver from their eyes. This led to a “holy war” against missionaries, foreigners and Chinese Christians. In the past, followers of Confucian teachings had already campaigned against them with pseudo-religious delusions. Pamphlets demonized the Jesuits around Matteo Ricci as alchemists who allegedly killed Chinese for this purpose.

Rumors could destroy political stability when social contradictions in society were severe. Only open information could have defused them, the magazine concludes. This remains unchanged today, when rumors, fake news and jokes are an expression of a deep-seated resentment of conditions.

Beijing takes this so seriously that it responded not only with the usual harsh suppression and expansion of censorship. In addition to COVID-19, China had to be wary of the danger of a “secondary epidemic” spread via rumors. Party leader Xi already ordered the creation of the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission (中央网络安全和信息化委员会) on August 29, 2018, to correct (alleged) rumors (辟谣平台). According to their website, more than 30,000 rumors have been reported to date, of which 9,000 have been red-stamped “false report”.

The Party and the state decide what is fake news or what is a rumor. But increasingly absurd conspiracy theories (阴谋论) are emanating not from bloggers, but from Party agencies like the Foreign Ministry. There, Foreign Office spokesman Zhao Lijian made a name for himself as a “wolf warrior” after he blamed the US for the Covid outbreak and even accused Washington of being involved in alleged biochemical weapons manufacturing experiments in Ukraine. Zhao pushed it so far – despite his appeals to patriotism – that Chinese bloggers have made him a target of their own scorn.

The web is filled with all forms of allusions to the party’s poor pandemic control. One blogger put a snail on a razor blade in a photo montage and wrote underneath: “It can’t go forward, it can’t go back. Standing still is not an option.”

Another blogger showed creativity by transforming the famous skyscraper silhouette of Pudong into a vegetable arrangement as his reproach to the authorities for failing to provide enough food for Shanghai’s citizens during the lockdown.

These political jokes are virtual slaps in the face to Xi, who constantly praises himself, the Party and his superior socialist system for how exemplary they have been in fighting the pandemic compared to the chaos in the West.

Bloggers are fighting back with jokes. In recent days, online collections of political jokes have appeared daily in Beijing under the heading “Beijing punchlines from yesterday.” (昨天北京人的段子). This is where, as long as Beijing’s residents can still go grocery shopping, survival lists for food are shared and what can be learned from the experience of the once hoity-toity Shanghainese who got blindsided by the lockdown: “Beijingers: buy freezers, so you’ll have a second fridge just in case.”

I witnessed similar virtual mass reactions like those currently happening in Shanghai and Beijing back in 2003. At the time, China’s leadership first denied the then predecessor disease SARS and then had it covered up, as it did in Wuhan in 2020. Only when there was no other way, Beijing mobilized the whole country to fight SARS.

At the time, the population was beside itself with anger on the Internet. The party initially tolerated their virtual criticism, used it as an outlet for emotions, and punished some higher officials. After a few months, everything was forgotten. China’s CP now turned the tables, declared itself the winner and settled accounts with activists.

Virtual mass anger and solidarity with the victims have erupted again and again over the past two years. Online outbursts of emotion “never last long. Nor do they lead to acts of resistance in China’s real world,” writes China expert James Palmer, editor of China Policy Brief: “Bloggers are taking a mild risk with their online postings. Real-world protests, however, have become even more dangerous under Xi’s rule.”

At the very least, the mass discontent on the Internet triggered by the lockdowns reveals the true mood of the people. If there were free elections and uncensored media in China, Xi would have a thing coming.

David Chin resigns as head of UBS China. He is the third executive of a global bank in China to step down this month, Bloomberg reports. Chin will be succeeded by Eugene Qian, Chairman of UBS Securities, after two years in the post.

Wanderlust? Someday, the Covid pandemic will end. Then, the Zhangjiajie Stone Pillars near Wulingyuan in Hunan Province could be a worthwhile visit. It has been a Unesco World Natural Heritage Site since 1992.