China remains by far the world’s largest CO2 emitter. Nevertheless, even after the current meeting in Bonn, which concerns the UN’s Green Climate Fund, the world’s second-largest economy will continue to abstain from international climate financing. The reason is that the People’s Republic still regards itself as a developing country.

The leadership’s concern is not just about willingness to contribute; the country, with the most substantial foreign exchange reserves globally, has plenty of money. If China were to participate in climate financing within the framework of the UN, it would also have to allow more transparency, as Nico Beckert points out in his Feature. In the authoritarian People’s Republic, control is paramount.

Climate is the focus of today’s second Feature as well. In it, Fabian Peltsch describes the fear of climate change, which also exists in China. No wonder: Weather extremes like months of heat followed by severe floods have severely affected people in the People’s Republic this summer.

However, the scarcity of climate protests, let alone climate graffiti on the streets, has less to do with a lack of discontent and more to do with repression, which ensures that any protest is immediately quashed. And there we are again, at the issue of control, which, as we know, reigns supreme in China.

In China, people worry about climate change just like anywhere else. However, taking to the streets or spraying paint on landmarks is not an option in this authoritarian state to vent their concerns. Nevertheless, the Chinese people already feel the effects of changing weather patterns in catastrophic ways. In January 2023, the Chinese Meteorological Administration declared that China’s climate in 2022 was clearly anomalous and trending towards extremes. The summer saw record-high temperatures and unexpected cold snaps occurred in the fall.

Surprisingly, there is hardly any public debate on this issue in state or social media. Researchers Chuxuan Liu and Jeremy Lee Wallace noted in their study “China’s missing climate change discourse” (2023) that only 0.12 percent of trending topics on Weibo, China’s leading social media platform, were related to climate change between June 2017 and February 2021. However, an end-of-2019 survey conducted by the European Investment Bank found that 73 percent of Chinese citizens considered climate change a major threat, compared to 47 percent in Europe and 39 percent in the United States. The difficulty of the issue’s prominence in China has several reasons.

Environmental organizations and NGOs face stricter scrutiny. In recent years, authorities have warned and arrested numerous environmental activists and whistleblowers while undermining citizen initiatives. A 2017 law also requires all foreign NGOs to cooperate with local groups, leading to increased self-censorship, according to many involved.

Bloomberg reports that journalists from state media are encouraged not to report on topics such as the threat to affluent coastal cities from rising sea levels. Investigative articles on environmental damage are limited to the wrongdoing of individual local government officials. Phenomena like the Friday for Future demonstrations in the West were portrayed in state media articles as emotional, radical and chaotic. Greta Thunberg is often a subject of ridicule on Chinese social media and is seen by many as a typical embodiment of the western “baizuo 白左”, a derogatory term for the woke Left that imposes its rules on others. Additionally, many conspiracy theories questioning the existence of climate change circulate in China’s online world. Young activist Howey Ou, who was briefly dubbed the “Chinese Greta”, now prefers to protest against climate change abroad.

Education in schools and media coverage primarily focus on how individuals can reduce their ecological footprint, such as through waste separation, recycling and environmentally conscious consumption. China’s role as the largest CO2 emitter in global warming is downplayed. The message is that China is not only striving to contribute to climate mitigation with green technology but also aims to become carbon-neutral by 2060, setting an example for other countries. However, China also insists on the right to develop at its own pace, arguing that humanity’s problems were primarily caused by the major Western industrial nations.

Environmentalists see the weak engagement of civil society as a missed opportunity. Even in the recent past, collective pressure in the People’s Republic has had the power to effect change. About a decade ago, a campaign against air pollution, supported by the population, prompted the Chinese leadership to seriously address the smog issue, especially in major cities. An important factor in this was the self-funded documentary film “Under the Dome” by Chinese journalist Chai Jing, which spread rapidly online, initially outrunning censorship.

Ultimately, the government fears the destabilizing impact of open activism too much. So, what happens to the population’s fears? Some believe that it finds an outlet in outrage over foreign environmental scandals and as a generally diffuse form of eco-anxiety. When Japan discharged wastewater from the Fukushima nuclear power plant into the sea in the summer, panic-buying occurred in China, especially for salt, even though there was no scientific basis for the panic.

In China’s still-thriving science fiction genre, which has hardly featured climate change until now, a change is emerging as well. Authors like Chen Qiufan and, more recently, Gu Shi are incorporating scenarios of environmental disasters and rising sea levels into their literary works. Both feature artificial intelligence as a countermeasure, aligning with the government’s goals, which view AI with similar optimism to how the US once viewed nuclear energy achievements. Beijing plans to use the technology in almost all areas of public life to save billions of tons of carbon emissions. This offers a vague hope, which keeps the Chinese from having to take to the streets en masse.

Today in Bonn, there is a significant discussion about money: The donor countries of the UN Green Climate Fund are gathering in the former federal capital to announce their contributions to the climate fund for the next four years. Some states, such as Germany, have already disclosed their pledges (two billion euros).

China has not yet participated in this fund and has not announced any plans to do so. On the contrary, the People’s Republic has so far refused to make its own contributions to the financing of climate action, adaptation or climate damage reduction within the UN framework. According to UN definitions, the world’s second-largest economy and by far the largest CO2 emitter is classified as a so-called Non-Annex-I country – mostly developing countries.

This classification was made by the UN in 1992. According to UN statutes, China is not required to participate in international climate financing, even though the country has since experienced an unprecedented economic boom: Per capita, economic power is 34 times higher than in 1992, and the state has accumulated trillions in currency reserves.

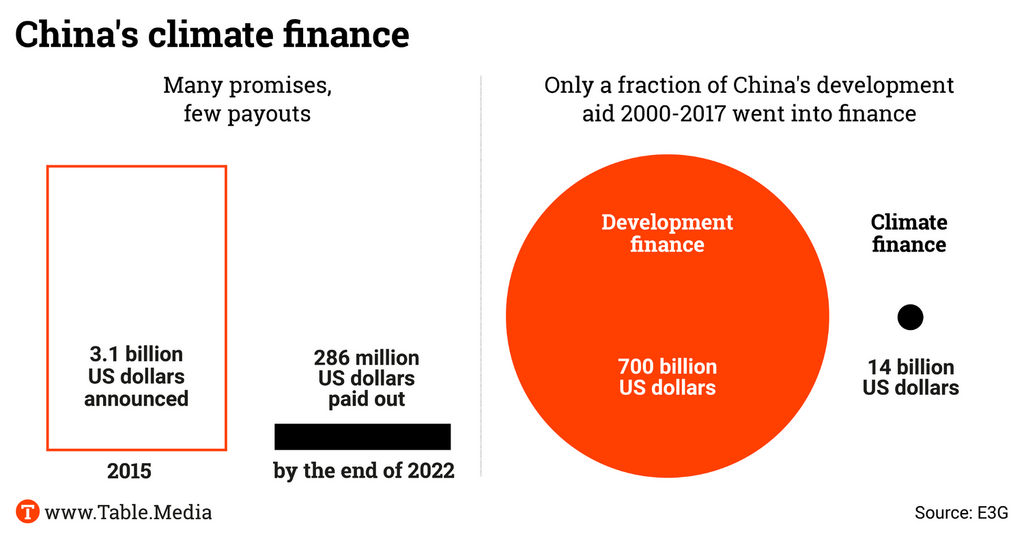

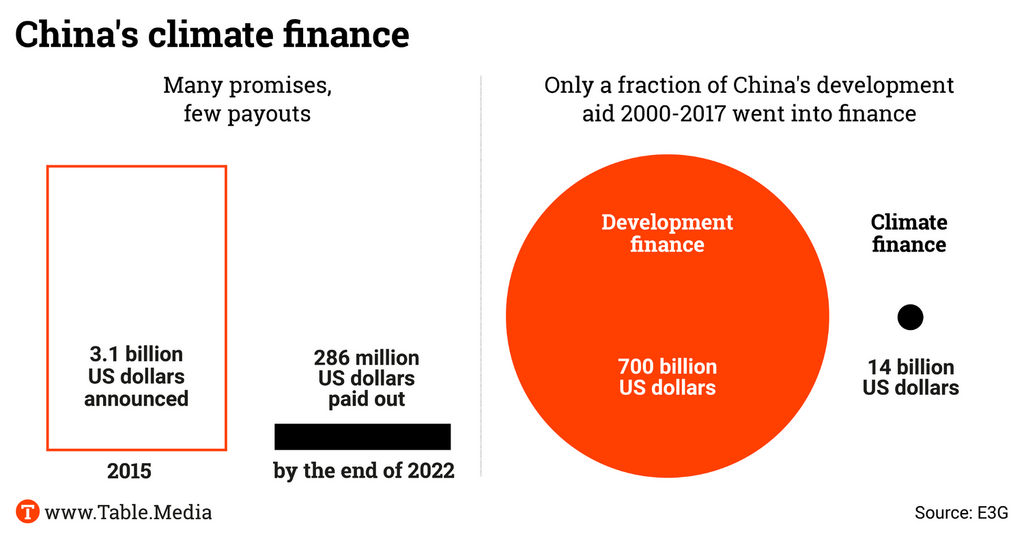

What China contributes to climate financing is, therefore, voluntary and is distributed through channels controlled by China. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), led by China, announced at the end of September that it would triple its climate financing to at least 7 billion dollars annually by 2030. However, experts criticize that China is not keeping its promises. While there have been bold announcements, only relatively small amounts have been paid out so far, and the payments are marked by significant opacity.

According to various studies, China provided between 14 billion and 17 billion dollars in climate financing from 2000 to 2017, according to researcher Nicolas Lippolis of the University of Oxford. The think tank E3G also criticizes the low level of Chinese climate financing. Since the launch of the “Belt and Road Initiative” in 2013, climate financing has averaged 1.4 billion dollars per year. However, it accounts for only two percent of China’s development financing. By comparison, according to government figures, Germany provided 6.3 billion dollars for climate financing in 2022.

Furthermore, China, like some Western countries, announces more than it actually pays. In 2015, the People’s Republic pledged 3.1 billion dollars for the “China South-South Climate Cooperation Fund.” According to E3G research, less than ten percent of this money, 286 million dollars, had been disbursed by the end of 2022.

Most of China’s money is also granted on “commercial terms,” according to Lippolis – partner countries rarely receive concessional loans. The fact that a large part of global climate financing – regardless of China – is provided in the form of loans also contributes to the debt problems of many Global South countries.

China’s initiatives in climate financing are dominated by bilateral, regional, and international partnerships, according to E3G. However, many of these projects and programs are characterized by a lack of transparency. E3G criticizes, for example, that “information on financial commitments and the implementation of projects under regional initiatives is sparse and vague.” Unlike other donor nations, China does not disclose whether a development financing measure is aligned with environmental or climate goals, writes Oxford researcher Lippolis. This further restricts transparency.

If China were to participate in climate financing within the UN framework, the country would have to accept greater transparency and would have less control over the use of the funds. “The main reason why China does not participate in UN climate funds is likely to be a fundamental one: For China, it is a strategic priority not to lose its status as a ‘developing country,’” says Martin Voss, climate diplomacy and cooperation officer at the environmental and development organization Germanwatch.

It is in “China’s geopolitical interest” to continue negotiating within the UN context with the group of developing countries (Group of 77), says Voss. However, “many developing countries expect more from China in compensating other developing countries,” says Gørild Heggelund, China expert at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute in Oslo. Expectations for China to increase climate financing are growing, says Heggelund.

In climate diplomacy, discussions are already underway about a financial target for the period after 2025, the so-called New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). Likewise, the fund for losses and damages caused by climate change, created at COP27, must be filled. After 2025, donor countries will probably have to spend larger sums than 100 billion dollars, which is the annual target until 2025. This greater need for funds could deter China from participating in UN funds. The NCQG is part of the Paris Climate Agreement, says Voss. Accordingly, China and other major emerging countries would only have to participate voluntarily.

However, the classic industrialized countries are pushing for China and other states to be obligated to pay into the NCQG, explains Voss. And in the future, China could also come under more pressure regarding the loss and damage fund. It does not fall under Article 9 of the Paris Climate Agreement, says Voss, so China’s status as a developing country does not protect it from participation.

With regard to the upcoming climate conference at the end of the year (COP28), Voss expects “no major concessions” from China. The People’s Republic is “in a comfortable negotiating position” and can point out that it has no payment obligations and that other states are not fully meeting their commitments. Voss also assumes that the United States “will not contribute more to climate financing than before, even if an ambitious NCQG were to be adopted.” This plays into China’s hands.

Byford Tsang of the E3G think tank says with regard to COP28: “The Chinese government should increase its funding for developing countries to help them adapt to climate change and strengthen their resilience to its effects.” China could present a “clear roadmap for the provision of the promised 3.1 billion dollars,” support the reform of multilateral development banks, or jointly with the COP host to “develop new and innovative financing sources based on a voluntary basis, such as independent climate investment funds outside the UNFCCC system.”

Politicians from both government and opposition parties are criticizing the use of equipment from the Chinese telecom provider Huawei in the data networks of Deutsche Bahn. Roderich Kiesewetter (CDU), Jens Zimmermann (SPD) and Maximilian Funke-Kaiser (FDP) accuse Deutsche Bahn, as reported by Handelsblatt, of continuing to use Chinese technology despite existing concerns. They demand that Deutsche Bahn replace the components in its data networks because they are considered part of Germany’s critical infrastructure.

Deutsche Bahn recently calculated that replacing the Huawei components would cost them 400 million euros. Additionally, the digital overhaul would be delayed by five to six years. Deutsche Bahn has been using Chinese components since 2015 and has built up a significant inventory.

As recently as December of last year, Deutsche Bahn indirectly chose to continue using the Chinese provider when it awarded the network expansion contract to Deutsche Telekom. Deutsche Telekom is a major customer of Huawei. At that time, the debate over Huawei had been ongoing for many years, and the Ministry of the Interior was already considering a ban on Huawei.

In a statement to Table.Media, Deutsche Bahn defended its position. “The awarding of services and products, even in critical infrastructure, is regulated through formal tender processes that comply with the applicable EU legal foundations and standards,” a spokesperson wrote. In such tenders, the company is obliged to choose the best offer. There is no way to simply exclude a single provider.

By taking this stance, Deutsche Bahn is shifting the responsibility back towards the politicians. If the government were to officially advise against using Huawei components, it could then adjust its tenders to comply with this advice. However, “there is no warning from the Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) regarding the use of Huawei components,” according to the spokesperson. If this were to change, the company would naturally respond accordingly. The BSI is an agency of the Ministry of the Interior. fin

The European Commission has initiated an investigation into state subsidies for Chinese EVs, as previously announced. The justification for this action is that such imports harm the EU economy. “The prices of these cars are artificially lowered through huge state subsidies – this distorts our market,” said von der Leyen in September during her State of the European Union address. This is unacceptable, she said. World markets are being flooded with cheaper Chinese EVs.

According to the EU Commission’s announcement, it has “collected sufficient evidence demonstrating that the manufacturers of the products under investigation originating in the People’s Republic of China receive various subsidies from the Chinese government”. The Brussels authority assumes that various subsidies are involved, including:

According to the commission’s data, Chinese EVs are usually about 20 percent cheaper than EU-manufactured models. The investigation into subsidies and harm will be conducted randomly and covers the period from Oct. 1, 2022, to Sept. 30, 2023, according to the announcement. The investigation could lead to tariffs being imposed on Chinese EVs.

The Ministry of Commerce in Beijing criticized this move. The EU is acting on purely subjective assumptions and not in accordance with the rules of the World Trade Organization, a spokesperson said on Wednesday. “The EU has demanded that China conduct negotiations in a very short time and has failed to provide documents for the negotiations, seriously violating the rights of the Chinese side,” the agency added.

The ministry called on the EU to create a fair environment for the development of the Chinese-European EV industry. China will closely monitor the investigation and protect the rights of its companies, the spokesperson said. ari

The crisis in the real estate sector is spreading. Following a missed interest and principal payment on a loan, China SCE warned on Wednesday that its cash flow might not be sufficient to meet current and future obligations. The property developer is now exploring options for restructuring all its liabilities.

According to the information, SCE was unable to make a 61 million dollar payment. As a result, creditors could demand early repayment of other obligations. However, no such demands have been received yet. Nevertheless, dollar bonds of the company are now being considered as a payment default. Consequently, trading in four of these bonds with a total volume of 1.8 billion dollars has been suspended.

Chinese real estate prices are falling due to a sluggish economy, while fresh loans are becoming more expensive. Prominent examples of the sector’s crisis include China Evergrande, the world’s most indebted real estate firm with 303 billion dollars in debt, and Country Garden. The industry accounts for a quarter of the economic output of the People’s Republic. rtr

The Cybersecurity Administration of China (CAC) has released a new set of draft regulations that, if passed, will considerably ease the restrictions on cross-border data transfer (CBDT) for foreign companies and multinationals. The Regulations on Standardizing and Promoting Cross-Border Data Flows (Draft for Comment) (the “draft regulations”) provide several allowances for the export of “important data” and personal information (PI) in certain scenarios, which, if passed, would alleviate uncertainties and compliance burdens for many companies. The CAC is soliciting public feedback on the draft regulations until October 15, 2023.

China has been significantly expanding its PI protection and data security legislation in recent years. This has included the roll-out of strict regulations on the export of PI and important data, with companies being required to undergo various security assessment and certification mechanisms in order to gain approval to transfer data overseas.

These requirements have caused significant disruption to both domestic and foreign companies that rely on the free flow of data for basic operations. The draft regulations can therefore be seen as a concerted effort to improve the business environment in China, in particular for foreign companies, as the country aims to boost economic recovery in the wake of the pandemic.

The regulations surrounding CBDT have been fleshed out over the last few years in a series of laws and regulatory documents. Chief among them is the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which requires companies that need to export a certain volume of data to undergo various compliance processes.

Article 38 of the PIPL stipulates that companies exporting the data collected from subjects in China must do one of the following depending on the volume and type of data being exported:

The CAC has subsequently released separate measures for each of the above mechanisms, excluding the final item. These measures not only outline how the requirements will be implemented but also stipulate the conditions under which companies must be subject to one of these mechanisms.

Under the measures for the implementation of the security assessment, the highest bar of compliance, a company must undergo a security assessment by the CAC in any of the following circumstances:

Meanwhile, companies can choose to undergo PI protection certification by a third-party agency or sign a standard contract with the overseas recipient if they fall below the above thresholds; that is, they are not a CIIO, they process the PI of under one million people, and they have cumulatively exported the PI of less than 100,000 people and the “sensitive” data of under 10,000 people since January 1 of the previous year.

The relatively low threshold for the volume of data a company can handle before it must undergo a security assessment means that many companies are now subject to this requirement.

In addition, the ambiguity over terms such as “important data” and “CIIO” has left many companies uncertain over whether their operations apply.

“Important data” has been defined in the security assessment measures as “data that may endanger national security, economic operation, social stability, or public health and safety once tampered with, destroyed, leaked, or illegally obtained or used”. However, the authorities haven’t yet released a reference document for the type of data that would be deemed to fall under this definition, leaving the definition largely up to interpretation.

Meanwhile, CIIOs have been defined in the Regulations on the Security and Protection of Critical Information Infrastructure as companies engaged in “important industries or fields”, including:

Whereas for some companies this classification will clearly apply-such as companies in fields such as power grids, public transport, military provision, and so on-for others it is more ambiguous. For instance, “any other important network facilities or information systems” could be interpreted to include major online service companies, such as Tencent’s WeChat or ride-hailing platform Didi.

The requirements for CBDT have been a cause for significant concern among foreign companies, MNCs, and foreign business groups in China. Foreign companies and multinationals are also particularly affected, as the cross-border nature of their operations means that they often have to export data outside of China.

China’s authorities have hinted at easing regulations surrounding CBDT for foreign companies several times, in particular since China reopened following the pandemic, and have strived to attract more foreign investment in an effort to boost economic recovery. In August 2023, a set of measures for optimizing the foreign investment environment from the State Council, China’s cabinet, called for establishing “green channels” for qualified foreign companies to export data, and to pilot a list of “general data” that can be transferred freely across the border in Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai.

The new draft regulations contain 11 proposals to ease the CBDT compliance burden for companies and “further standardize and promote the orderly and free flow of data in accordance with the law”.

The draft regulations waive the requirement for companies to undergo any of the three compliance processes (security assessment, PI protection certification, or standard contract) to export data, if the data generated does not contain any PI or important data and is generated in activities, such as international trade, academic cooperation, transnational manufacturing, and marketing.

Whereas this still hinges upon the definition of “important data”, the draft regulations also stipulate that if the data in question has not already been declared as “important data” by relevant government departments, through a regional notice, or through public notice, then the company is not required to undergo a security assessment. In other words, if the data has not been officially specified as “important”, then it will not be treated as such for the purpose of CBDT.

The draft regulations also clarify that companies do not need to undergo any of the three CBDT mechanisms in order to export PI that has not been collected or generated in China.

The draft regulations go on to stipulate scenarios in which the export of PI is deemed necessary and therefore are not subject to the three CBDT mechanisms. These scenarios are also items under Article 13 of the PIPL, which stipulates the scenarios in which a company is permitted to process the PI of a subject.

These scenarios are where:

The draft regulations slightly shift the thresholds of the volume of data that a company can export before they need to undergo a certain CBDT mechanism.

The draft regulations state that if a company expects to export the PI of less than 10,000 people within a year, then they do not need to undergo any CBDT mechanisms. As mentioned above, current regulations state that any company that has cumulatively exported the normal PI of under 100,000 thousand people or sensitive PI of under 10,000 people since January 1 of the previous year must either undergo PI protection certification or sign a standard contract with the overseas recipient.

The fact that the draft security regulations change the wording from “cumulative” to “expected” amounts also suggests that companies will be allowed to estimate the amount of data that they will process in a given year, rather than basing their status on past activity. However, the draft regulations do not say what will happen if a company exceeds the expected amount in a given year.

The draft regulations propose for China’s free trade zones (FTZs) to formulate data “negative lists” of certain types of data for which a company must undergo one of the CBDT mechanisms and receive approval from the CAC to export.

Under this system, any data types that are not included in the negative list could be freely exported through the FTZs, without the company needing to undergo any CBDT requirements.

If passed in their current form, the draft regulations will make compliance with China’s CBDT regulations significantly easier for many foreign companies. For instance, the clause which allows companies to export potentially important data without undergoing the CBDT mechanisms-if the important data has not been specifically defined-addresses a key concern for foreign companies and business groups.

In its European Business in China Position Paper 2023/2024 released last month, the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China (EU Chamber) notes the lack of a clear definition for important data, and “urges for the scope of important data to be clearly and narrowly defined, with regulators providing a sufficient grace period between any future releases of guidelines related to the definition of ‘important data’ and catalogues, and their implementation”.

While the draft regulations do not provide a definition for important data, they would allow companies whose applications for data export have been denied due to their inclusion of undefined important data to have these decisions potentially overturned, at least until the authorities provide a specific definition. This will help to alleviate uncertainty and greatly facilitate companies’ normal operations in the interim.

The EU’s Position Paper also takes issue with the fact that the security assessment mechanism for CBDT “can be easily triggered by most large firms and consumer-facing firms” due to the low threshold of data volume for this mechanism. The draft regulations proposal to raise the thresholds for the various CBDT mechanisms (and security assessment mechanism in particular) will be beneficial, particularly to smaller companies dealing with smaller volumes of data, which perhaps do not have the staff or budget to handle the added administrative burden.

Of course, companies that handle large volumes of data will in many cases still be subject to the CBDT mechanisms. However, the addition of specific scenarios for which they are not required will benefit these companies in handling specific tasks.

This article first appeared in China Briefing, written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong.

James Royds-Jones and Wanny Wu will lead the new Greater China team at private jet and cargo company Air Charter Service. This will include offices in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Beijing. The French group says it aims to expand its presence in the Asian region.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Suspense to the top: Yang Hao competes in the preliminary round of the ten-meter diving at the Asia Games.

China remains by far the world’s largest CO2 emitter. Nevertheless, even after the current meeting in Bonn, which concerns the UN’s Green Climate Fund, the world’s second-largest economy will continue to abstain from international climate financing. The reason is that the People’s Republic still regards itself as a developing country.

The leadership’s concern is not just about willingness to contribute; the country, with the most substantial foreign exchange reserves globally, has plenty of money. If China were to participate in climate financing within the framework of the UN, it would also have to allow more transparency, as Nico Beckert points out in his Feature. In the authoritarian People’s Republic, control is paramount.

Climate is the focus of today’s second Feature as well. In it, Fabian Peltsch describes the fear of climate change, which also exists in China. No wonder: Weather extremes like months of heat followed by severe floods have severely affected people in the People’s Republic this summer.

However, the scarcity of climate protests, let alone climate graffiti on the streets, has less to do with a lack of discontent and more to do with repression, which ensures that any protest is immediately quashed. And there we are again, at the issue of control, which, as we know, reigns supreme in China.

In China, people worry about climate change just like anywhere else. However, taking to the streets or spraying paint on landmarks is not an option in this authoritarian state to vent their concerns. Nevertheless, the Chinese people already feel the effects of changing weather patterns in catastrophic ways. In January 2023, the Chinese Meteorological Administration declared that China’s climate in 2022 was clearly anomalous and trending towards extremes. The summer saw record-high temperatures and unexpected cold snaps occurred in the fall.

Surprisingly, there is hardly any public debate on this issue in state or social media. Researchers Chuxuan Liu and Jeremy Lee Wallace noted in their study “China’s missing climate change discourse” (2023) that only 0.12 percent of trending topics on Weibo, China’s leading social media platform, were related to climate change between June 2017 and February 2021. However, an end-of-2019 survey conducted by the European Investment Bank found that 73 percent of Chinese citizens considered climate change a major threat, compared to 47 percent in Europe and 39 percent in the United States. The difficulty of the issue’s prominence in China has several reasons.

Environmental organizations and NGOs face stricter scrutiny. In recent years, authorities have warned and arrested numerous environmental activists and whistleblowers while undermining citizen initiatives. A 2017 law also requires all foreign NGOs to cooperate with local groups, leading to increased self-censorship, according to many involved.

Bloomberg reports that journalists from state media are encouraged not to report on topics such as the threat to affluent coastal cities from rising sea levels. Investigative articles on environmental damage are limited to the wrongdoing of individual local government officials. Phenomena like the Friday for Future demonstrations in the West were portrayed in state media articles as emotional, radical and chaotic. Greta Thunberg is often a subject of ridicule on Chinese social media and is seen by many as a typical embodiment of the western “baizuo 白左”, a derogatory term for the woke Left that imposes its rules on others. Additionally, many conspiracy theories questioning the existence of climate change circulate in China’s online world. Young activist Howey Ou, who was briefly dubbed the “Chinese Greta”, now prefers to protest against climate change abroad.

Education in schools and media coverage primarily focus on how individuals can reduce their ecological footprint, such as through waste separation, recycling and environmentally conscious consumption. China’s role as the largest CO2 emitter in global warming is downplayed. The message is that China is not only striving to contribute to climate mitigation with green technology but also aims to become carbon-neutral by 2060, setting an example for other countries. However, China also insists on the right to develop at its own pace, arguing that humanity’s problems were primarily caused by the major Western industrial nations.

Environmentalists see the weak engagement of civil society as a missed opportunity. Even in the recent past, collective pressure in the People’s Republic has had the power to effect change. About a decade ago, a campaign against air pollution, supported by the population, prompted the Chinese leadership to seriously address the smog issue, especially in major cities. An important factor in this was the self-funded documentary film “Under the Dome” by Chinese journalist Chai Jing, which spread rapidly online, initially outrunning censorship.

Ultimately, the government fears the destabilizing impact of open activism too much. So, what happens to the population’s fears? Some believe that it finds an outlet in outrage over foreign environmental scandals and as a generally diffuse form of eco-anxiety. When Japan discharged wastewater from the Fukushima nuclear power plant into the sea in the summer, panic-buying occurred in China, especially for salt, even though there was no scientific basis for the panic.

In China’s still-thriving science fiction genre, which has hardly featured climate change until now, a change is emerging as well. Authors like Chen Qiufan and, more recently, Gu Shi are incorporating scenarios of environmental disasters and rising sea levels into their literary works. Both feature artificial intelligence as a countermeasure, aligning with the government’s goals, which view AI with similar optimism to how the US once viewed nuclear energy achievements. Beijing plans to use the technology in almost all areas of public life to save billions of tons of carbon emissions. This offers a vague hope, which keeps the Chinese from having to take to the streets en masse.

Today in Bonn, there is a significant discussion about money: The donor countries of the UN Green Climate Fund are gathering in the former federal capital to announce their contributions to the climate fund for the next four years. Some states, such as Germany, have already disclosed their pledges (two billion euros).

China has not yet participated in this fund and has not announced any plans to do so. On the contrary, the People’s Republic has so far refused to make its own contributions to the financing of climate action, adaptation or climate damage reduction within the UN framework. According to UN definitions, the world’s second-largest economy and by far the largest CO2 emitter is classified as a so-called Non-Annex-I country – mostly developing countries.

This classification was made by the UN in 1992. According to UN statutes, China is not required to participate in international climate financing, even though the country has since experienced an unprecedented economic boom: Per capita, economic power is 34 times higher than in 1992, and the state has accumulated trillions in currency reserves.

What China contributes to climate financing is, therefore, voluntary and is distributed through channels controlled by China. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), led by China, announced at the end of September that it would triple its climate financing to at least 7 billion dollars annually by 2030. However, experts criticize that China is not keeping its promises. While there have been bold announcements, only relatively small amounts have been paid out so far, and the payments are marked by significant opacity.

According to various studies, China provided between 14 billion and 17 billion dollars in climate financing from 2000 to 2017, according to researcher Nicolas Lippolis of the University of Oxford. The think tank E3G also criticizes the low level of Chinese climate financing. Since the launch of the “Belt and Road Initiative” in 2013, climate financing has averaged 1.4 billion dollars per year. However, it accounts for only two percent of China’s development financing. By comparison, according to government figures, Germany provided 6.3 billion dollars for climate financing in 2022.

Furthermore, China, like some Western countries, announces more than it actually pays. In 2015, the People’s Republic pledged 3.1 billion dollars for the “China South-South Climate Cooperation Fund.” According to E3G research, less than ten percent of this money, 286 million dollars, had been disbursed by the end of 2022.

Most of China’s money is also granted on “commercial terms,” according to Lippolis – partner countries rarely receive concessional loans. The fact that a large part of global climate financing – regardless of China – is provided in the form of loans also contributes to the debt problems of many Global South countries.

China’s initiatives in climate financing are dominated by bilateral, regional, and international partnerships, according to E3G. However, many of these projects and programs are characterized by a lack of transparency. E3G criticizes, for example, that “information on financial commitments and the implementation of projects under regional initiatives is sparse and vague.” Unlike other donor nations, China does not disclose whether a development financing measure is aligned with environmental or climate goals, writes Oxford researcher Lippolis. This further restricts transparency.

If China were to participate in climate financing within the UN framework, the country would have to accept greater transparency and would have less control over the use of the funds. “The main reason why China does not participate in UN climate funds is likely to be a fundamental one: For China, it is a strategic priority not to lose its status as a ‘developing country,’” says Martin Voss, climate diplomacy and cooperation officer at the environmental and development organization Germanwatch.

It is in “China’s geopolitical interest” to continue negotiating within the UN context with the group of developing countries (Group of 77), says Voss. However, “many developing countries expect more from China in compensating other developing countries,” says Gørild Heggelund, China expert at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute in Oslo. Expectations for China to increase climate financing are growing, says Heggelund.

In climate diplomacy, discussions are already underway about a financial target for the period after 2025, the so-called New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). Likewise, the fund for losses and damages caused by climate change, created at COP27, must be filled. After 2025, donor countries will probably have to spend larger sums than 100 billion dollars, which is the annual target until 2025. This greater need for funds could deter China from participating in UN funds. The NCQG is part of the Paris Climate Agreement, says Voss. Accordingly, China and other major emerging countries would only have to participate voluntarily.

However, the classic industrialized countries are pushing for China and other states to be obligated to pay into the NCQG, explains Voss. And in the future, China could also come under more pressure regarding the loss and damage fund. It does not fall under Article 9 of the Paris Climate Agreement, says Voss, so China’s status as a developing country does not protect it from participation.

With regard to the upcoming climate conference at the end of the year (COP28), Voss expects “no major concessions” from China. The People’s Republic is “in a comfortable negotiating position” and can point out that it has no payment obligations and that other states are not fully meeting their commitments. Voss also assumes that the United States “will not contribute more to climate financing than before, even if an ambitious NCQG were to be adopted.” This plays into China’s hands.

Byford Tsang of the E3G think tank says with regard to COP28: “The Chinese government should increase its funding for developing countries to help them adapt to climate change and strengthen their resilience to its effects.” China could present a “clear roadmap for the provision of the promised 3.1 billion dollars,” support the reform of multilateral development banks, or jointly with the COP host to “develop new and innovative financing sources based on a voluntary basis, such as independent climate investment funds outside the UNFCCC system.”

Politicians from both government and opposition parties are criticizing the use of equipment from the Chinese telecom provider Huawei in the data networks of Deutsche Bahn. Roderich Kiesewetter (CDU), Jens Zimmermann (SPD) and Maximilian Funke-Kaiser (FDP) accuse Deutsche Bahn, as reported by Handelsblatt, of continuing to use Chinese technology despite existing concerns. They demand that Deutsche Bahn replace the components in its data networks because they are considered part of Germany’s critical infrastructure.

Deutsche Bahn recently calculated that replacing the Huawei components would cost them 400 million euros. Additionally, the digital overhaul would be delayed by five to six years. Deutsche Bahn has been using Chinese components since 2015 and has built up a significant inventory.

As recently as December of last year, Deutsche Bahn indirectly chose to continue using the Chinese provider when it awarded the network expansion contract to Deutsche Telekom. Deutsche Telekom is a major customer of Huawei. At that time, the debate over Huawei had been ongoing for many years, and the Ministry of the Interior was already considering a ban on Huawei.

In a statement to Table.Media, Deutsche Bahn defended its position. “The awarding of services and products, even in critical infrastructure, is regulated through formal tender processes that comply with the applicable EU legal foundations and standards,” a spokesperson wrote. In such tenders, the company is obliged to choose the best offer. There is no way to simply exclude a single provider.

By taking this stance, Deutsche Bahn is shifting the responsibility back towards the politicians. If the government were to officially advise against using Huawei components, it could then adjust its tenders to comply with this advice. However, “there is no warning from the Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) regarding the use of Huawei components,” according to the spokesperson. If this were to change, the company would naturally respond accordingly. The BSI is an agency of the Ministry of the Interior. fin

The European Commission has initiated an investigation into state subsidies for Chinese EVs, as previously announced. The justification for this action is that such imports harm the EU economy. “The prices of these cars are artificially lowered through huge state subsidies – this distorts our market,” said von der Leyen in September during her State of the European Union address. This is unacceptable, she said. World markets are being flooded with cheaper Chinese EVs.

According to the EU Commission’s announcement, it has “collected sufficient evidence demonstrating that the manufacturers of the products under investigation originating in the People’s Republic of China receive various subsidies from the Chinese government”. The Brussels authority assumes that various subsidies are involved, including:

According to the commission’s data, Chinese EVs are usually about 20 percent cheaper than EU-manufactured models. The investigation into subsidies and harm will be conducted randomly and covers the period from Oct. 1, 2022, to Sept. 30, 2023, according to the announcement. The investigation could lead to tariffs being imposed on Chinese EVs.

The Ministry of Commerce in Beijing criticized this move. The EU is acting on purely subjective assumptions and not in accordance with the rules of the World Trade Organization, a spokesperson said on Wednesday. “The EU has demanded that China conduct negotiations in a very short time and has failed to provide documents for the negotiations, seriously violating the rights of the Chinese side,” the agency added.

The ministry called on the EU to create a fair environment for the development of the Chinese-European EV industry. China will closely monitor the investigation and protect the rights of its companies, the spokesperson said. ari

The crisis in the real estate sector is spreading. Following a missed interest and principal payment on a loan, China SCE warned on Wednesday that its cash flow might not be sufficient to meet current and future obligations. The property developer is now exploring options for restructuring all its liabilities.

According to the information, SCE was unable to make a 61 million dollar payment. As a result, creditors could demand early repayment of other obligations. However, no such demands have been received yet. Nevertheless, dollar bonds of the company are now being considered as a payment default. Consequently, trading in four of these bonds with a total volume of 1.8 billion dollars has been suspended.

Chinese real estate prices are falling due to a sluggish economy, while fresh loans are becoming more expensive. Prominent examples of the sector’s crisis include China Evergrande, the world’s most indebted real estate firm with 303 billion dollars in debt, and Country Garden. The industry accounts for a quarter of the economic output of the People’s Republic. rtr

The Cybersecurity Administration of China (CAC) has released a new set of draft regulations that, if passed, will considerably ease the restrictions on cross-border data transfer (CBDT) for foreign companies and multinationals. The Regulations on Standardizing and Promoting Cross-Border Data Flows (Draft for Comment) (the “draft regulations”) provide several allowances for the export of “important data” and personal information (PI) in certain scenarios, which, if passed, would alleviate uncertainties and compliance burdens for many companies. The CAC is soliciting public feedback on the draft regulations until October 15, 2023.

China has been significantly expanding its PI protection and data security legislation in recent years. This has included the roll-out of strict regulations on the export of PI and important data, with companies being required to undergo various security assessment and certification mechanisms in order to gain approval to transfer data overseas.

These requirements have caused significant disruption to both domestic and foreign companies that rely on the free flow of data for basic operations. The draft regulations can therefore be seen as a concerted effort to improve the business environment in China, in particular for foreign companies, as the country aims to boost economic recovery in the wake of the pandemic.

The regulations surrounding CBDT have been fleshed out over the last few years in a series of laws and regulatory documents. Chief among them is the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which requires companies that need to export a certain volume of data to undergo various compliance processes.

Article 38 of the PIPL stipulates that companies exporting the data collected from subjects in China must do one of the following depending on the volume and type of data being exported:

The CAC has subsequently released separate measures for each of the above mechanisms, excluding the final item. These measures not only outline how the requirements will be implemented but also stipulate the conditions under which companies must be subject to one of these mechanisms.

Under the measures for the implementation of the security assessment, the highest bar of compliance, a company must undergo a security assessment by the CAC in any of the following circumstances:

Meanwhile, companies can choose to undergo PI protection certification by a third-party agency or sign a standard contract with the overseas recipient if they fall below the above thresholds; that is, they are not a CIIO, they process the PI of under one million people, and they have cumulatively exported the PI of less than 100,000 people and the “sensitive” data of under 10,000 people since January 1 of the previous year.

The relatively low threshold for the volume of data a company can handle before it must undergo a security assessment means that many companies are now subject to this requirement.

In addition, the ambiguity over terms such as “important data” and “CIIO” has left many companies uncertain over whether their operations apply.

“Important data” has been defined in the security assessment measures as “data that may endanger national security, economic operation, social stability, or public health and safety once tampered with, destroyed, leaked, or illegally obtained or used”. However, the authorities haven’t yet released a reference document for the type of data that would be deemed to fall under this definition, leaving the definition largely up to interpretation.

Meanwhile, CIIOs have been defined in the Regulations on the Security and Protection of Critical Information Infrastructure as companies engaged in “important industries or fields”, including:

Whereas for some companies this classification will clearly apply-such as companies in fields such as power grids, public transport, military provision, and so on-for others it is more ambiguous. For instance, “any other important network facilities or information systems” could be interpreted to include major online service companies, such as Tencent’s WeChat or ride-hailing platform Didi.

The requirements for CBDT have been a cause for significant concern among foreign companies, MNCs, and foreign business groups in China. Foreign companies and multinationals are also particularly affected, as the cross-border nature of their operations means that they often have to export data outside of China.

China’s authorities have hinted at easing regulations surrounding CBDT for foreign companies several times, in particular since China reopened following the pandemic, and have strived to attract more foreign investment in an effort to boost economic recovery. In August 2023, a set of measures for optimizing the foreign investment environment from the State Council, China’s cabinet, called for establishing “green channels” for qualified foreign companies to export data, and to pilot a list of “general data” that can be transferred freely across the border in Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai.

The new draft regulations contain 11 proposals to ease the CBDT compliance burden for companies and “further standardize and promote the orderly and free flow of data in accordance with the law”.

The draft regulations waive the requirement for companies to undergo any of the three compliance processes (security assessment, PI protection certification, or standard contract) to export data, if the data generated does not contain any PI or important data and is generated in activities, such as international trade, academic cooperation, transnational manufacturing, and marketing.

Whereas this still hinges upon the definition of “important data”, the draft regulations also stipulate that if the data in question has not already been declared as “important data” by relevant government departments, through a regional notice, or through public notice, then the company is not required to undergo a security assessment. In other words, if the data has not been officially specified as “important”, then it will not be treated as such for the purpose of CBDT.

The draft regulations also clarify that companies do not need to undergo any of the three CBDT mechanisms in order to export PI that has not been collected or generated in China.

The draft regulations go on to stipulate scenarios in which the export of PI is deemed necessary and therefore are not subject to the three CBDT mechanisms. These scenarios are also items under Article 13 of the PIPL, which stipulates the scenarios in which a company is permitted to process the PI of a subject.

These scenarios are where:

The draft regulations slightly shift the thresholds of the volume of data that a company can export before they need to undergo a certain CBDT mechanism.

The draft regulations state that if a company expects to export the PI of less than 10,000 people within a year, then they do not need to undergo any CBDT mechanisms. As mentioned above, current regulations state that any company that has cumulatively exported the normal PI of under 100,000 thousand people or sensitive PI of under 10,000 people since January 1 of the previous year must either undergo PI protection certification or sign a standard contract with the overseas recipient.

The fact that the draft security regulations change the wording from “cumulative” to “expected” amounts also suggests that companies will be allowed to estimate the amount of data that they will process in a given year, rather than basing their status on past activity. However, the draft regulations do not say what will happen if a company exceeds the expected amount in a given year.

The draft regulations propose for China’s free trade zones (FTZs) to formulate data “negative lists” of certain types of data for which a company must undergo one of the CBDT mechanisms and receive approval from the CAC to export.

Under this system, any data types that are not included in the negative list could be freely exported through the FTZs, without the company needing to undergo any CBDT requirements.

If passed in their current form, the draft regulations will make compliance with China’s CBDT regulations significantly easier for many foreign companies. For instance, the clause which allows companies to export potentially important data without undergoing the CBDT mechanisms-if the important data has not been specifically defined-addresses a key concern for foreign companies and business groups.

In its European Business in China Position Paper 2023/2024 released last month, the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China (EU Chamber) notes the lack of a clear definition for important data, and “urges for the scope of important data to be clearly and narrowly defined, with regulators providing a sufficient grace period between any future releases of guidelines related to the definition of ‘important data’ and catalogues, and their implementation”.

While the draft regulations do not provide a definition for important data, they would allow companies whose applications for data export have been denied due to their inclusion of undefined important data to have these decisions potentially overturned, at least until the authorities provide a specific definition. This will help to alleviate uncertainty and greatly facilitate companies’ normal operations in the interim.

The EU’s Position Paper also takes issue with the fact that the security assessment mechanism for CBDT “can be easily triggered by most large firms and consumer-facing firms” due to the low threshold of data volume for this mechanism. The draft regulations proposal to raise the thresholds for the various CBDT mechanisms (and security assessment mechanism in particular) will be beneficial, particularly to smaller companies dealing with smaller volumes of data, which perhaps do not have the staff or budget to handle the added administrative burden.

Of course, companies that handle large volumes of data will in many cases still be subject to the CBDT mechanisms. However, the addition of specific scenarios for which they are not required will benefit these companies in handling specific tasks.

This article first appeared in China Briefing, written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong.

James Royds-Jones and Wanny Wu will lead the new Greater China team at private jet and cargo company Air Charter Service. This will include offices in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Beijing. The French group says it aims to expand its presence in the Asian region.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Suspense to the top: Yang Hao competes in the preliminary round of the ten-meter diving at the Asia Games.