The EU Commission is expected to make good on its threat on Monday and impose punitive tariffs on Chinese EV imports. The most interesting question will be: How high will they be? After all, it is certain that tariffs will come.

This marks the EU’s shift away from the ordoliberalism that the Germans, in particular, have upheld in recent decades and towards a strategic industrial policy.

An economic system in which the state only sets the framework and otherwise allows citizens the freedom to compete is, without a doubt, the much more appealing concept. After all, the counter-model is a strong state that constantly intervenes in economic activity and actively participates in it. We Europeans have fared well for many decades with a freely operating middle class.

But times have changed, making other measures necessary: China has emerged as a player that has been feeding its industry with massive subsidies and state aid to such an extent that even healthy top companies can no longer keep up. Its massive overcapacities are wreaking havoc on entire industries around the world. This has already happened in the solar industry and now threatens to do the same to European car manufacturers.

It remains uncertain whether punitive tariffs are the appropriate response and whether they will work at all in light of Chinese predatory pricing. But in this situation, remaining passive, doing nothing and relying on the market to sort things out is more than negligent. Once an industry has been ruined, it will not return for a while. This is also shown by the experience of the solar industry, where the Germans were once the frontrunners, but where developments are now almost exclusively taking place in China.

In today’s issue, Amelie Richter summarizes what will be decided in Brussels on Monday and its potential impact.

The European Commission will likely announce the provisional tariffs on Chinese electric cars early next week. EU circles have suggested Monday, the day after the European elections, as a possible date. However, the Commission has not yet officially confirmed the date.

What else is China doing to prevent the looming measures?

Beijing appears to be still trying to prevent the EU tariffs, which are considered a certainty at this stage – and is using different methods to do so. During his visit to Spain, Trade Minister Wang Wentao warned that “protectionism is not a solution, but a dangerous dead end” and reminded the EU that any measures against Chinese electric cars would mean “a real loss of money.”

During a visit to Greece, Vice Minister of Commerce Ling Ji sharply criticized the EU for the anti-subsidy investigations under the Foreign Subsidies Regulation. If the EU insists on continuing to suppress Chinese companies, “China has the right and sufficient capability to take measures to defend the legitimate interests of its companies,” China Daily, which is regarded as one of the mouthpieces of the leadership in Beijing, quoted Ling as saying.

The same article also emphasizes China’s willingness to engage in dialogue to resolve the trade disputes. In addition, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce reportedly sent a letter to EU Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis asking for a ceasefire in the simmering trade war, as reported by Politico.

What is the backstory?

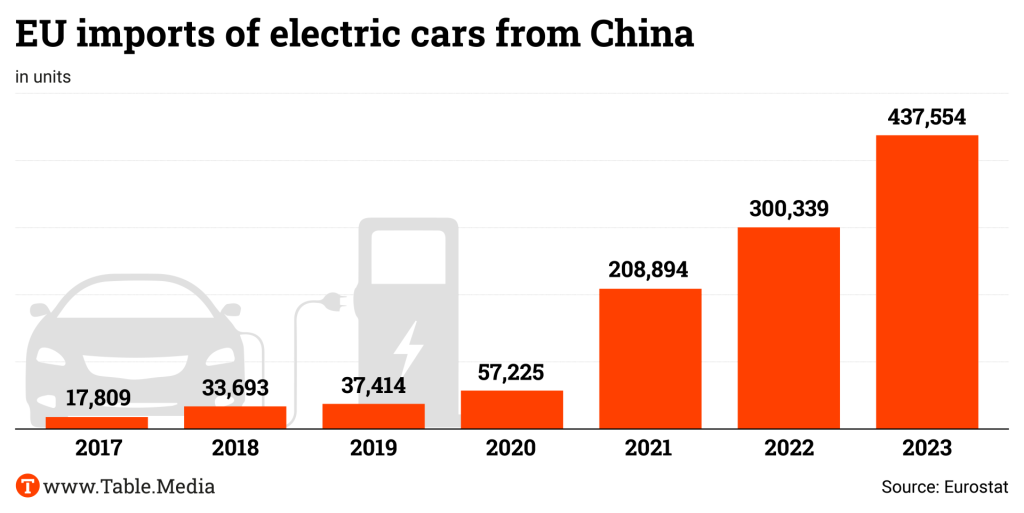

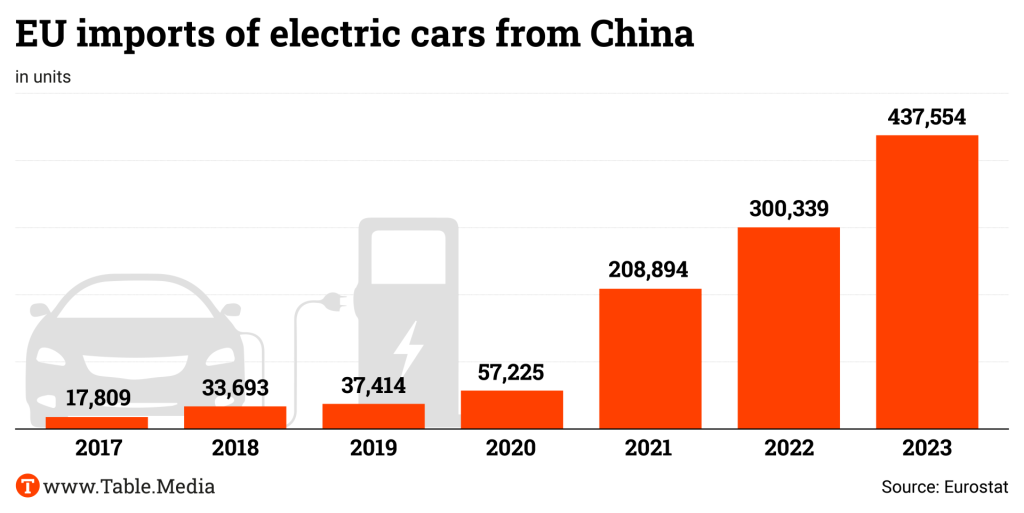

As part of the Green Deal, the EU has legally committed itself to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030. After difficult negotiations, the member states and the European Parliament agreed to ban the sale of new gasoline-powered cars by 2035, which would make EVs the standard. At the same time, the Chinese economy increased its exports to compensate for weak domestic demand. Chinese electric cars sold well, partly due to their lower prices. The export numbers of Chinese EVs to the EU increased.

Which subsidies does Brussels suspect?

When it announced the investigation in October, the EU Commission listed the state subsidies suspected to be involved: Direct transfers of funds and potential direct transfers of funds or liabilities, i.e., direct financial injections, as well as lost or uncollected state revenue, such as tax breaks. The provision of goods or services by the state for inadequate remuneration is also scrutinized. This includes, for example, the sale of raw and input materials at reduced prices or the provision of labor, some of which is then paid for by the state.

What is still unclear?

The tariffs’ exact amount is still a well-kept secret by the Brussels authority.

What tariff rate do experts expect?

The EU has already imposed a tariff of ten percent on Chinese EVs. The tariffs now decided upon will be added to this. Based on previous anti-subsidy investigations, the Rhodium Group expects a level of 15 to 30 percent, with rates tailored to BYD, Geely and SAIC. The NGO Transport and Environment stated that a 25 percent tariff would make European EVs more competitive against their Chinese rivals and generate additional revenue of between three and six billion euros. Meanwhile, the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) estimates that a tariff of 20 percent would lead to “noticeable trade shifts.”

What consequences will higher tariffs have?

Chinese companies can cushion the impact by selling their products in Europe at a significantly higher price than in China. Furthermore, Chinese brands could circumvent the tariffs by setting up plants in EU countries, as BYD is already planning to do in Hungary. The IfW expects imports of electric cars manufactured in China to drop by 25 percent.

Could this be the start of a trade war?

It is almost certain that Beijing will take retaliatory measures. So far, no Chinese authority has officially announced any measures. However, the state newspaper Global Times has directly threatened various steps through insiders and experts. The focus could be on the European agriculture and aviation industries. Import tariffs on spirits have been mentioned; this could primarily affect cognac from France. Tariffs on cars with larger combustion engines have also been suggested.

Can the tariffs still be stopped?

Not for now, but theoretically in the long term: If the EU Commission proposes permanent tariffs in November, the proposal will be put to the member states for a vote. However, a qualified majority is required to abolish the tariffs: 15 member states representing at least 65 percent of the bloc’s population must vote against the proposal. Alternatively, the EU Commission could also close the investigation and abolish the tariffs – but only if the subsidies under investigation are withdrawn.

The race for the best Chinese AI language model is intensifying. In a recent study, researchers from Beijing’s Tsinghua University identified Baidu’s Ernie Bot 4.0 and the GLM-4 model from start-up Zhipu AI as the country’s best language models (LLMs).

However, the researchers say that both services lag well behind foreign models such as OpenAI’s GPT-4. According to the results published in April, the Western models are clearly superior, particularly with regard to understanding, programming and following instructions – in other words, in all key areas.

Many experts believe that China could be up to two years behind the US in the development of LLMs. However, Tsinghua University suggests that the gap is constantly narrowing. Chinese companies are at a distinct development disadvantage because they do not have access to the latest generation of Western AI chips with which the models are trained. However, China’s catching-up race benefits from the massive competition in its tech sector and the country’s start-up culture.

According to the South China Morning Post, around 200 Chinese companies have already launched their own language models and are constantly improving them. The situation is reminiscent of the early days of the Chinese EV industry. In addition to the traditional car companies, numerous young start-ups entered the market looking to develop advanced vehicles. They had access to extensive funding sources from both state and private investors. These investments allow start-ups to invest in research and development and scale their technologies quickly.

Giants like Baidu, Alibaba and Huawei are all on the AI language model bandwagon. However, there is also a whole range of very young companies that have quickly made a name for themselves. They also have well-known tech companies on board as investors.

The hottest AI start-up is Zhipu AI, with over 800 employees and a 2.5 billion US dollar valuation. A close connection to the renowned Tsinghua University in Beijing, where Zhipu was founded, gives the company access to the country’s talented professionals. Zhipu’s chatbots focus strongly on efficiency in professional and academic contexts and provide clear, precise answers.

Moonshot AI is also experiencing rapid growth. Recently, the company was also valued at around 2.5 billion dollars. Moonshot focuses primarily on the chatbot Kimi, which it has developed specifically for contextualizing information. Other newly crowned AI unicorns with a valuation of over one billion euros include MiniMax and 01.ai, which was founded by well-known AI expert Kai-Fu Lee. These companies are already called the “four new AI tigers” in China.

Companies are engaged in a fierce battle for the best staff and the most talented university graduates, experts in the tech metropolis of Shenzhen say. China is investing heavily in education and research in the field of AI. Many of its universities and research institutes are world leaders in AI research. This leads to the world’s largest number of well-trained AI graduates and specialists.

But they are not only trying to poach the best employees from each other. There is also apparently a lot of poaching going on among foreign competitors. Microsoft has reportedly just asked its China-based cloud computing and AI employees to consider moving abroad. According to the Wall Street Journal, around 700 to 800 employees, mainly Chinese engineers, have been offered the chance to move to countries such as the United States, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. Microsoft is primarily concerned with geopolitical considerations. The US company apparently does not want to do without its Chinese talent in the event of escalating tensions.

June 10-11, 2024

Merics, Workshop (in Brussels): European China Policy Track 1.5 Workshop More

June 10-12, 2024

Trade fair (in Berlin) Taiwan Expo Europe More

June 13, 2024; 10 a.m. (4 p.m. Beijing time)

EU SME Center, Online Workshop: Biotech in China: Assessing Market Opportunities for European SMEs More

June 13-14, 2024

German Chamber of Commerce in China, Insight Tour in Zhaoqing New Area, Guangdong: Hidden Champions in Zhaoqing New Energy Vehicle Industry More

June 18, 2024; 3 p.m. Beijing time

German Chamber of Commerce in China, Policy Briefing (Members free) – in Shenzhen: Immigration & Exit and Entry Policy More

China’s investments in Europe once again declined last year: At 6.8 billion euros, they reached their lowest level since 2010, according to a study published on Thursday by the Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies (Merics) and the Rhodium Group. “Chinese greenfield projects in Europe are a positive development, but the overall low level of investment activity indicates an imbalance in economic relations,” Merics chief economist Max Zenglein said.

According to the study, almost half of Chinese direct investment in Europe flowed to Hungary last year, namely 44 percent. “The Eastern European country therefore attracted more Chinese investment than the three major economies of Germany, France and the UK combined,” Zenglein said.

Chinese companies invested in Hungary primarily in the automotive industry and particularly in electromobility. These accounted for two-thirds (69 percent) of China’s direct investments in Europe last year. The European healthcare industry is also meeting with strong interest from Chinese investors, with a particularly high level of interest in medical devices, which accounted for two-thirds of Chinese investment in this sector between 2021 and 2023.

Hungary has become an important trading partner for China under right-wing Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. China’s President Xi Jinping visited the country in May. Xi declared that relations with Hungary had now developed into an “all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership.” Orbán said that cooperation in nuclear energy was to be intensified, among other things. According to Xi, other projects, such as train connections in Hungary, are also being pursued. rtr

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), only China and Latin American countries have expanded their renewables capacity fast enough in 2022. By 2030, the People’s Republic could expand its capacity by a factor of 2.5 compared to 2022 – this corresponds to 45 percent of the capacity growth required to achieve the global target. The IEA estimates that this would be a sufficiently high contribution. However, China currently also consumes 30 percent of the electricity generated worldwide.

The IEA warns that other countries’ efforts are insufficient. New data shows that even if all countries implement their current plans and targets for the expansion of renewable energies, they would still fall 30 percent short of the global target of tripling capacity by 2030. The IEA states that the national plans would result in a renewable capacity of almost 8,000 gigawatts in 2030 – although tripling renewables and a 1.5-degree pathway would require over 11,000 gigawatts.

The IEA estimates that Europe, the countries of the Asia-Pacific region, the USA and Canada would have to accelerate expansion by several dozen gigawatts per year. In the Middle East, North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa, the rate of expansion would have to double – albeit from a very low level – in order to achieve the national plans. nib

China continues to focus on electric mobility, while investment in Europe is declining. With this argument, the organization Transport and Environment (T&E) is calling for clarity regarding the phase-out of combustion engines. According to the AFP news agency, T&E Managing Director Sebastian Bock said that the automotive industry needs “planning certainty from politicians.” And he warns that the competition from the USA and China is “clearly focussing on e-mobility with investments in the billions.”

A T&E report published on Thursday states that Europe has only secured around a quarter of the investments in electric cars announced worldwide over the past three years. “Investment from foreign manufacturers is needed to secure the location,” warned Bock and, also in light of China’s industrial strength, called for the EU to “urgently develop a strategy” to “keep the supply chains of the cars of the future, which will undoubtedly be electric, in Europe.” flee

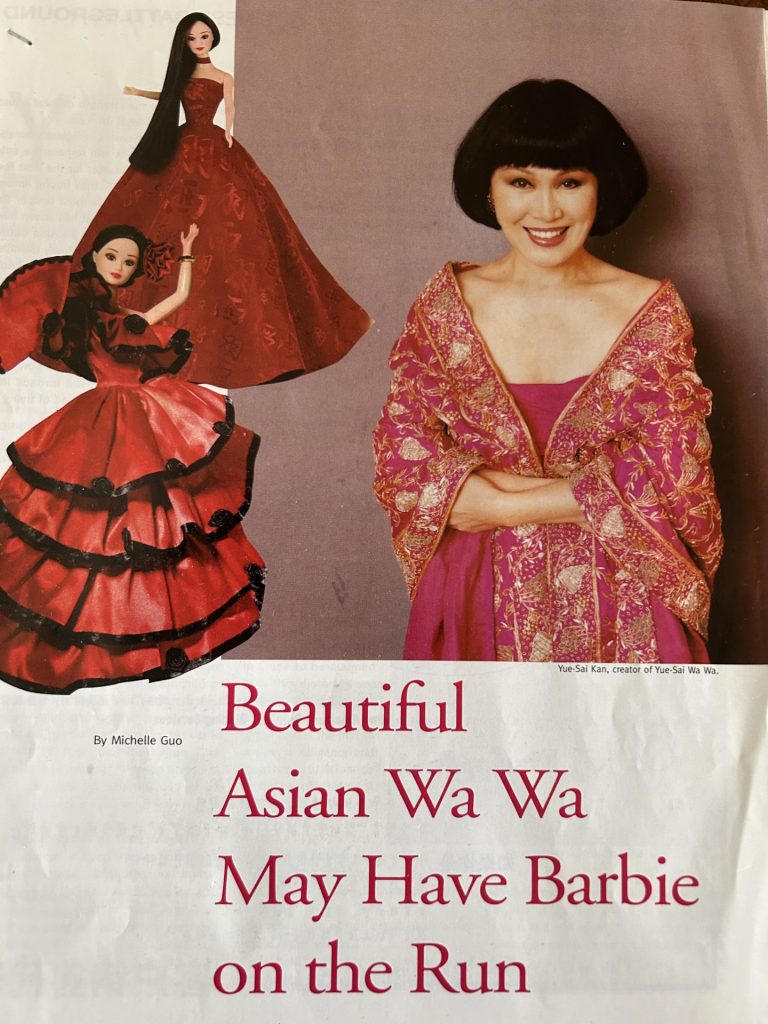

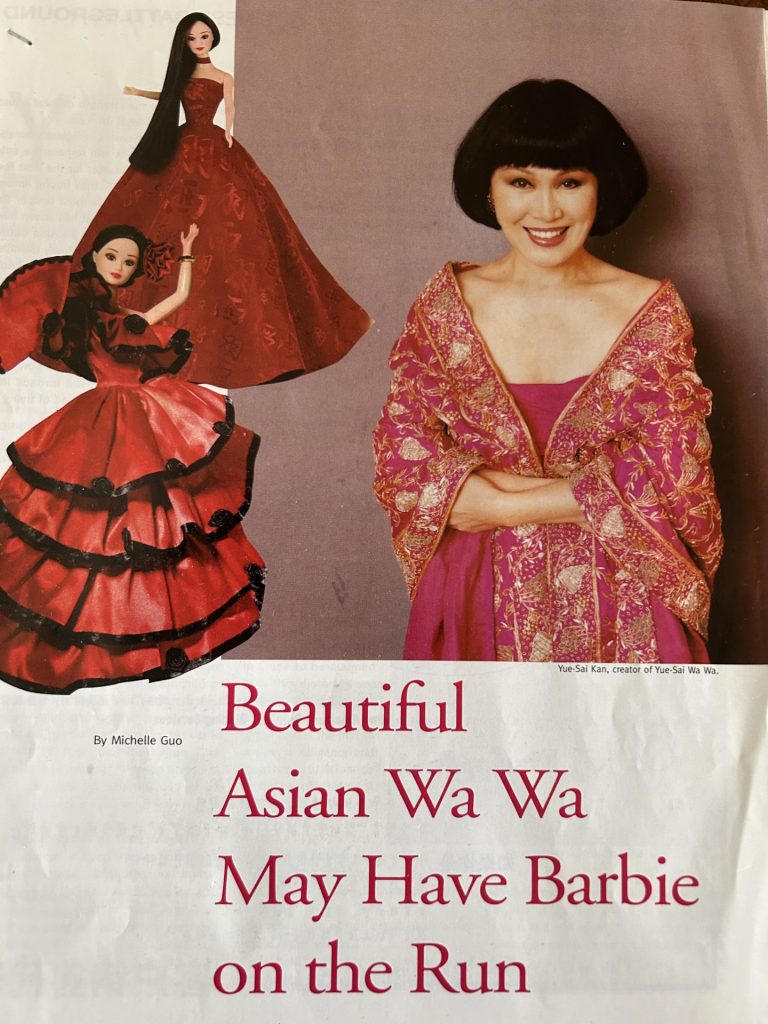

After the end of the Cultural Revolution, China’s reforms also introduced personal freedoms, fashion, cosmetics, polite manners and long-lost toys to its ideologically and sartorially uniformed women. European fashion designers such as Pierre Cardin were the first to explore the new market. In the early 1980s, they were followed by Yue-Sai Kan, a Chinese expat living in the USA. Known as the “most famous woman in China,” she taught her compatriots how to behave and how to wear make-up. In 2000, she designed Asian dolls for Chinese girls to pre-empt the import of US glamor girl Barbie 芭比. But unexpectedly for everyone, neither Yue-Sai’s black-haired China Doll nor the blonde Barbie was popular with children in the socialist People’s Republic: It was because of the parents. The dolls were too expensive for them. And girls were supposed to learn – instead of playing with foreign dolls.

My wife, Zhao Yuanhong, who studies the influence of playing on children’s education, was twelve years old in 1966 when she first saw a doll at the height of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. “We had to join the Cultural Revolution as little Red Guards,” she recalled. “Playing in our free time was ostracized as bourgeois, just like learning at school. We followed the example set by the big Red Guards.” They invaded the homes of functionaries and intellectuals, denouncing them as opponents of Mao: “For us children, it was like a big game.”

Yuanhong’s group of adults, students and children tagging along also broke into the ground-floor Beijing courtyard home of economist and philosopher Yu Guangyuan (1915-2013). They rummaged through his rooms and cupboards, tore books from the shelves and searched for incriminating possessions. “We wanted to help the big guys find ‘black’ material.”

Suddenly, a child discovered a small box with a mirror and the petite figure of a dancer. “We called out to Yu: What is that?” “A toy doll,” he replied. “Surely you’ve never seen anything like it? Bring me a smooth surface. Then I’ll show you how it dances.” The scholar placed the figure on the lid of a wooden case. As he approached with the mirror, the doll started to spin. “We bombarded him with questions,” my wife Yuanhong remembers. How does that work? When Yu saw them so amazed, he said: “Did you ever hear in school that magnets attract and repel each other?” The children shook their heads. They tried to make the doll dance. Yu helped patiently and seemed amused. Yuanhong recounts, “We forgot everything around us until a Red Guard came into the room and shouted at Yu: “You reactionary element! What are you doing?”

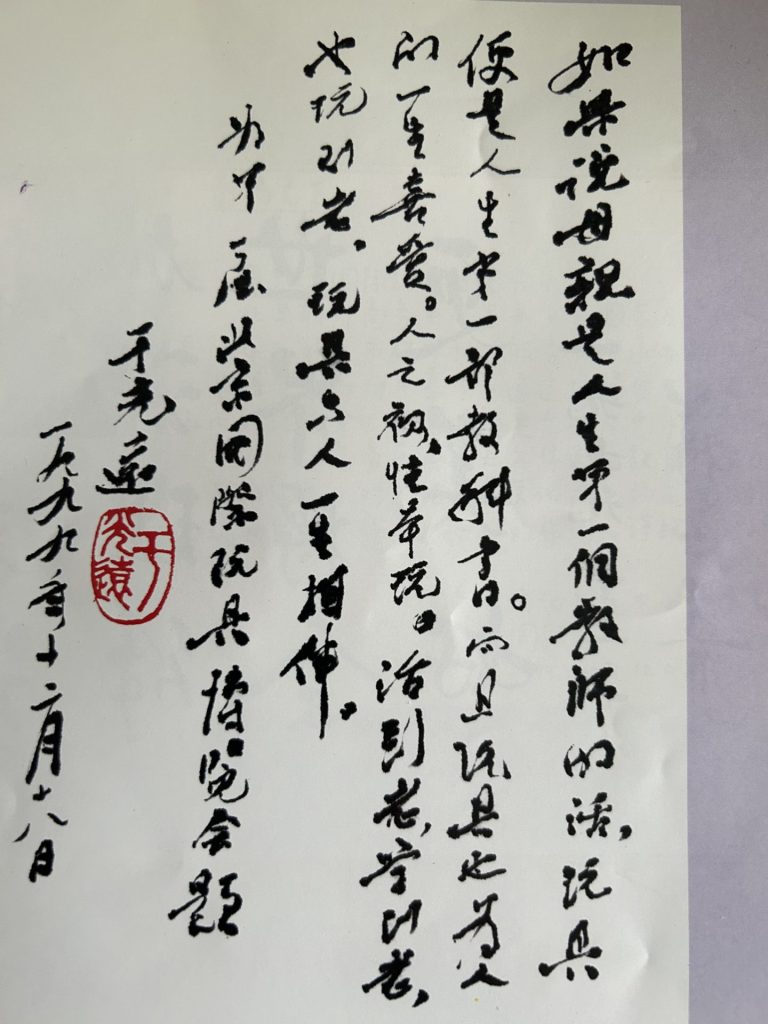

Twenty years later, my wife sent her memories of the incident to the rehabilitated and now highly respected Science Councilor Yu. He included the anecdote in his book “Persimmon Blossoms in My Garden.” In it, he called on the state and society to return to the cultural and humanistically important significance of playing and toys. He said that researchers and educators should make this their focus. Yu wrote the guidelines for a textbook on the subject.

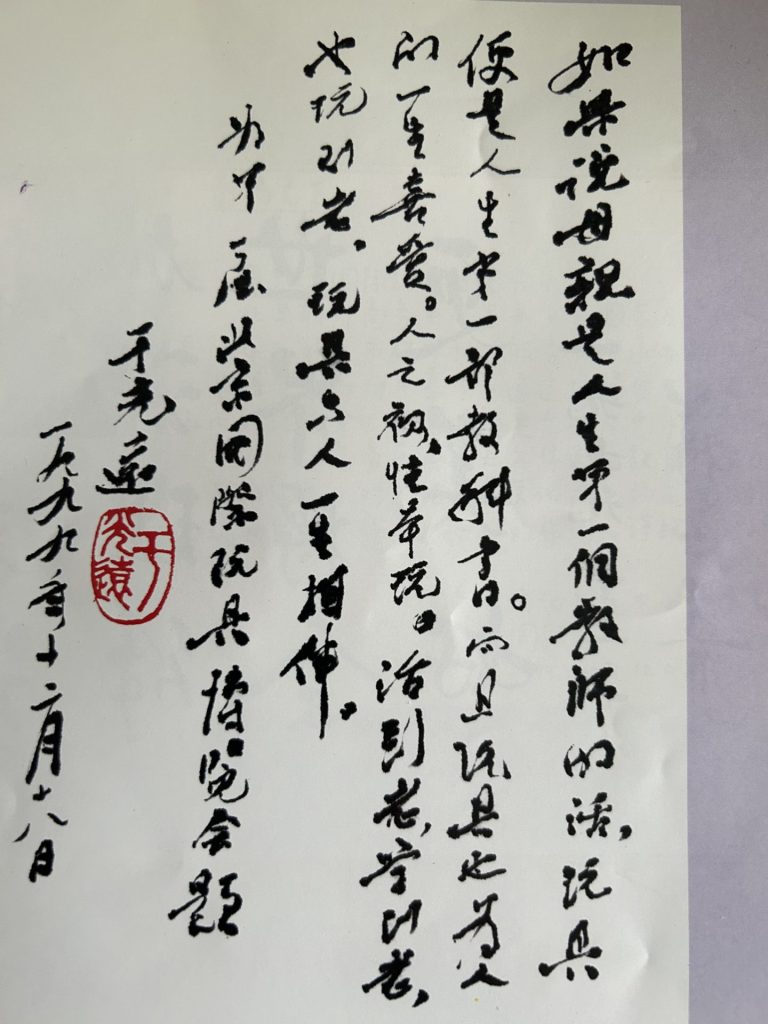

In 1993, Yu sparked controversy with his view that playing should be depoliticized. He argued that it was one of the essentials in every person’s life to give them the strength, energy and distraction to cope with other needs and goals. “A person should not only learn as long as they live, but also play into old age,” he demanded. As honorary chairman of Beijing’s first international toy fair in 1999, his calligraphed foreword read: “If the mother is the first teacher in a person’s life, then toys are his textbook for life.”

The socialist People’s Republic and its ideologues saw things differently. Like all totalitarian social systems, the leadership placed early childhood education and all play beneath the primacy of politics. The radical Cultural Revolution outlawed playing as bourgeois. Toys were no longer allowed to be sold. One father recounted how he once made a wooden car for his son. He labeled it with Mao slogans so that his son could play without having to worry.

After Mao’s death, everyday life became less tense and market reforms and the opening up of the economy also boosted personal consumption. The population control enforced after 1980 created a demand for toys among the growing generation of only children. Yue-Sai Kan靳羽西, a Chinese expatriate who became famous in the USA thanks to her TV show “Looking East,” recognized this early on. China’s CCTV hired her as a star presenter, who over 300 million Chinese people soon watched. Her guidebooks became bestsellers and she founded a cosmetics chain with 800 boutiques. In 2004, France’s L’Oreal took over her stores.

But her “patriotic” doll series for China’s girls failed. The Yue-Sai Doll 羽西娃娃 presented in Beijing in November 2000 – a black-haired beauty with Asian features and accessories ranging from qipao to red flamenco dance dresses – can now only be found on collector websites.

Even the hyped-up Barbie doll fared no better in China. Knock-offs were sold everywhere at a tenth of the price of the two plastic dolls. Above all, they were culturally alien. China had been cut off from the world and its trends for too long.

Like many US companies, Barbie manufacturer Mattel initially failed to understand what made China’s consumers tick or their relationship with playing. Dozens of studies explain why Barbie flopped in China. One said: “Mattel ignored the fact that parents demanded that their children study hard instead of playing.” Learning was again the highest Confucian virtue of Chinese education. To make matters worse, Barbie was too feminine, had boys on her mind and wore make-up.

Apparently, Mattel had fallen into a “cultural trap.” Instead, educational toys aimed at promoting cognitive skills became successful. Lego was the big winner in China’s market.

Mattel learned the hard way when it tried to force success. The US company converted a large old movie theater in the heart of Shanghai into a six-story Barbie flagship store, the largest in the world, at a cost of 30 million US dollars. Its “House of Barbie,” which opened in 2009, offered everything related to its cult doll with 1,600 products. When Mattel had to close its dream department store in 2011, two years after opening, critics mocked the “nightmare in pink.”

However, the US toy multinational succeeded on a completely different terrain with Barbie. It discovered the People’s Republic early on as a workbench for the production of toys. In 2002, Mattel closed its last US factory in West Kentucky (Murry). From then on, toys worldwide almost always bore the label “made in China.”

Even today, over 70 percent of the toys sold worldwide come from 20 areas of the People’s Republic, primarily from Guangdong. Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Thailand, Vietnam and India are only gradually emerging as manufacturers. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, its impact on the reliability of supply routes and the pressure to reduce dependence on China, a debate about de-risking has also begun in the toy industry.

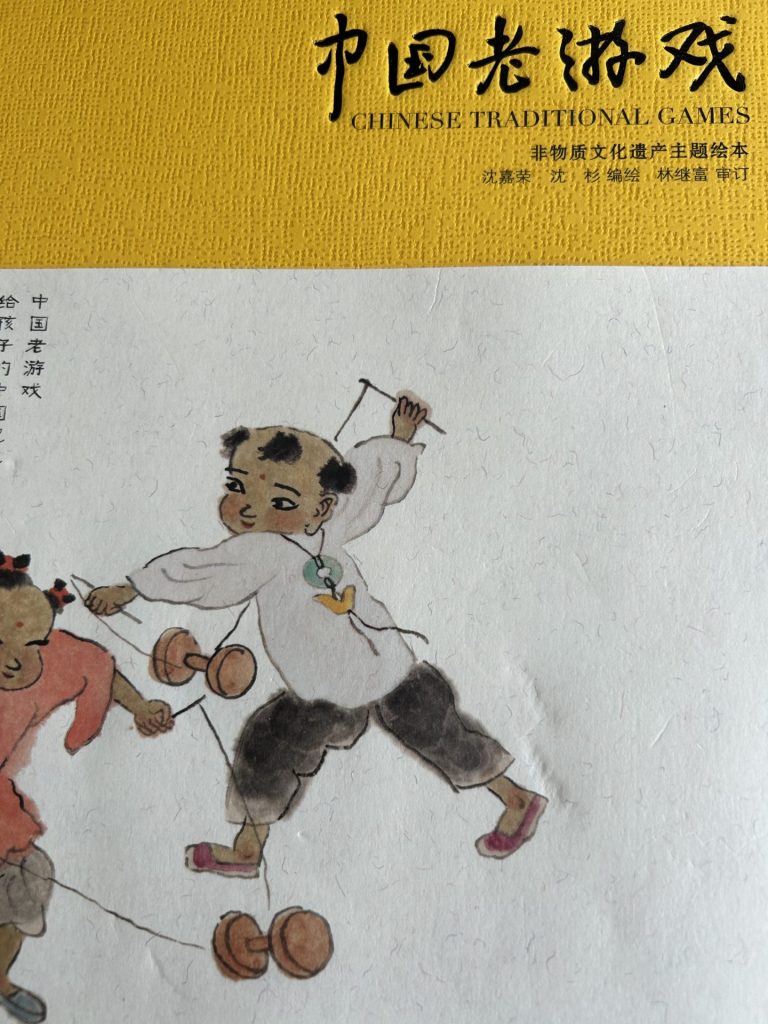

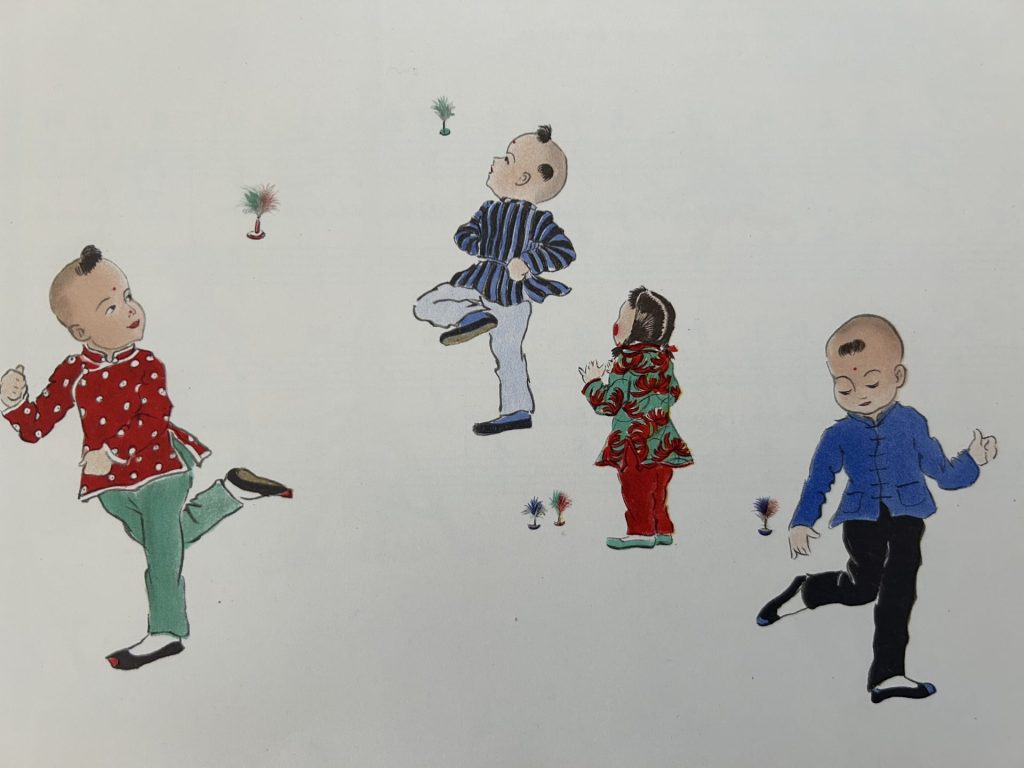

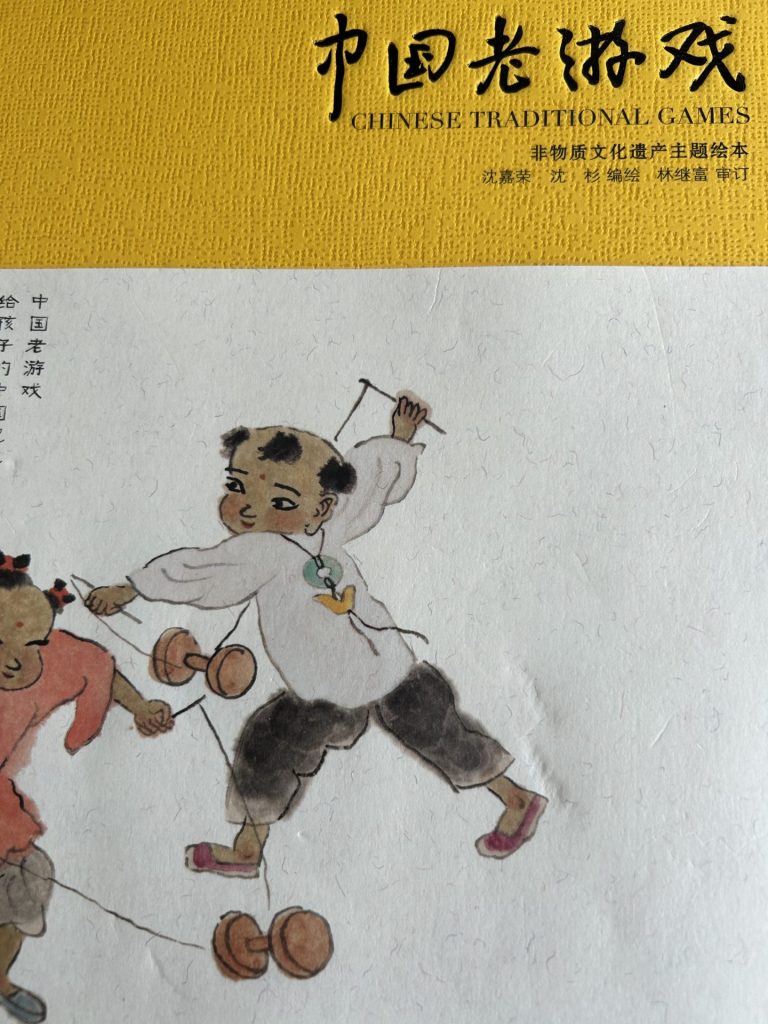

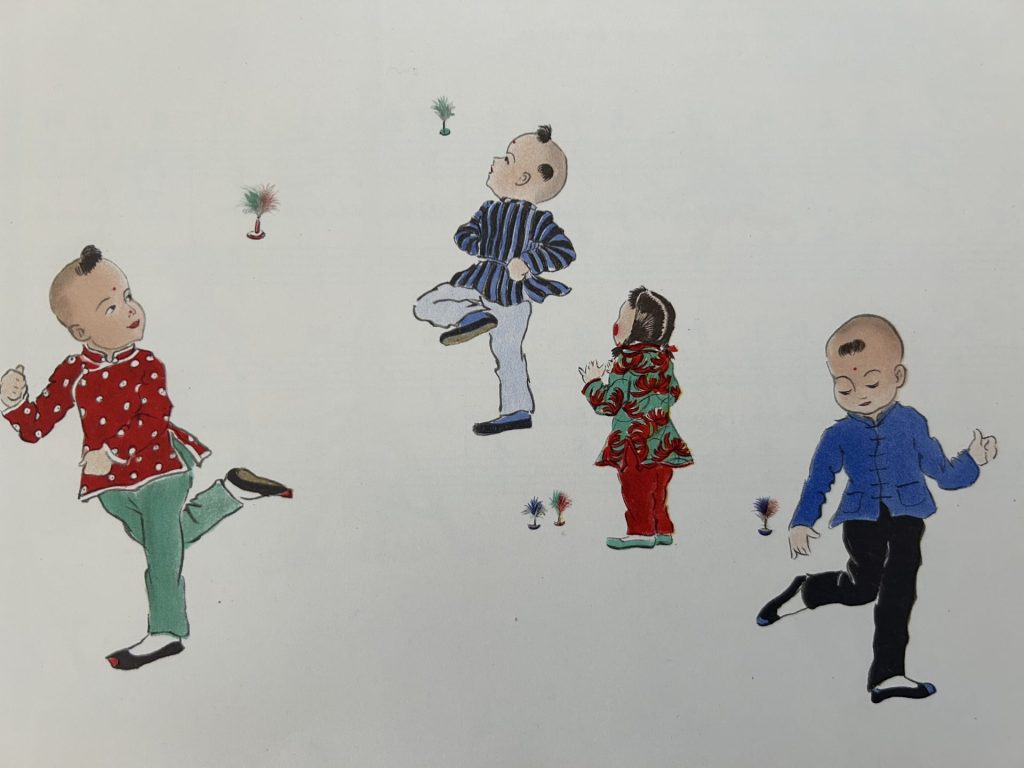

China itself is returning to its history of playing and traditional toys. “Do China’s kids have their own Barbie?” asked the cultural magazine “The World of Chinese” in late 2023. Toy dolls existed 1,000 years ago and evolved from ritual cult figures.

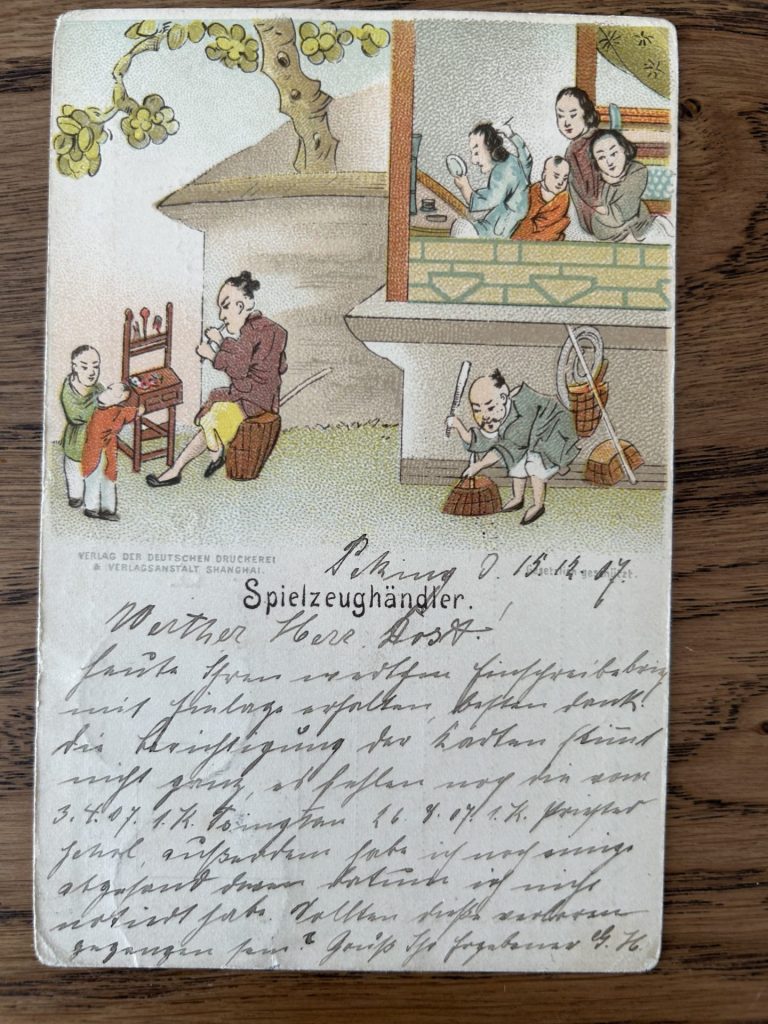

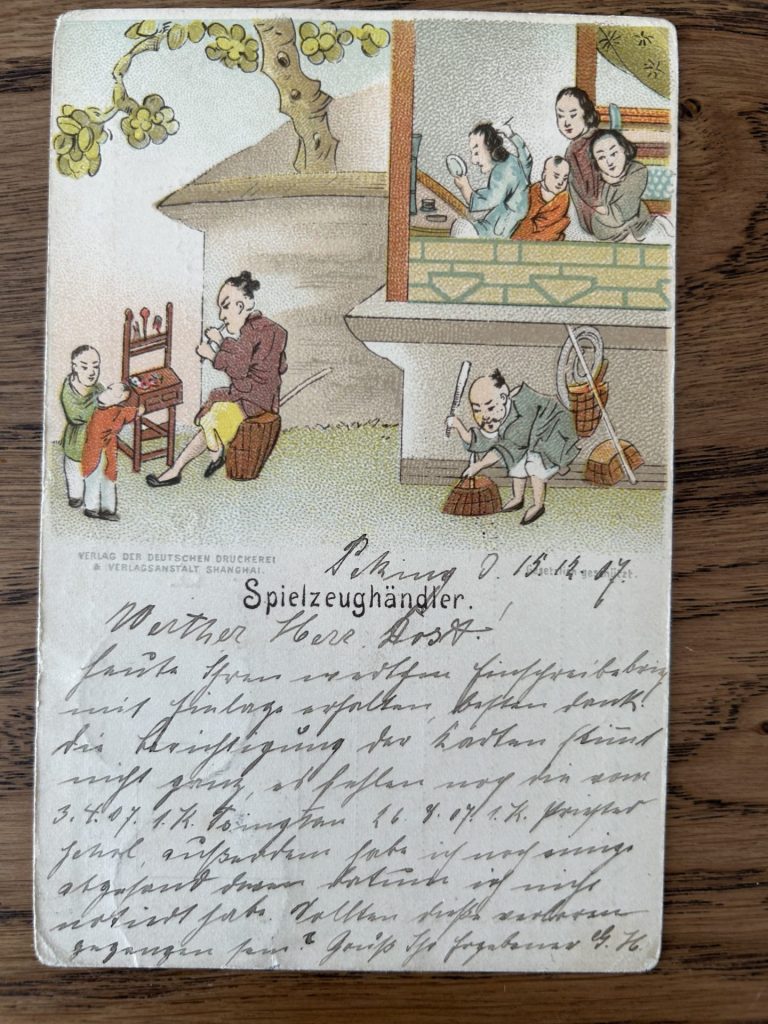

Toy sellers were already a familiar sight in cities in the 19th century. When foreign colonial powers forcibly seized concession territories, their soldiers and merchants sent home postcards with folklore motifs featuring toy vendors. They offered dolls and animal figurines kneaded from dough, which are still sold at New Year’s markets today.

Most of the more than 100 traditional children’s games have been lost. Researchers and historians are trying to reconstruct and recreate them. “Do you still remember?” asked another medium. Several games, including diabolo 抖空竹 or the shadow puppet game 皮影戏, are China’s cultural heritage and are also on the UNESCO list.

Chinese educators, ecologists and architects are interested in the effects that playing has on early childhood development. The playful connection with nature, with grasses, plants and insects, helps to counteract the barrenness of Chinese cities. In March 2024, 66 percent of the total population already lived in urban centers. For the first time, the new 14th five-year plan includes the government’s task of ensuring child-friendly and play-friendly spaces in cities. Also, for the first time, China is one of 17 countries that want to address this issue as part of UNICEF since 2020,

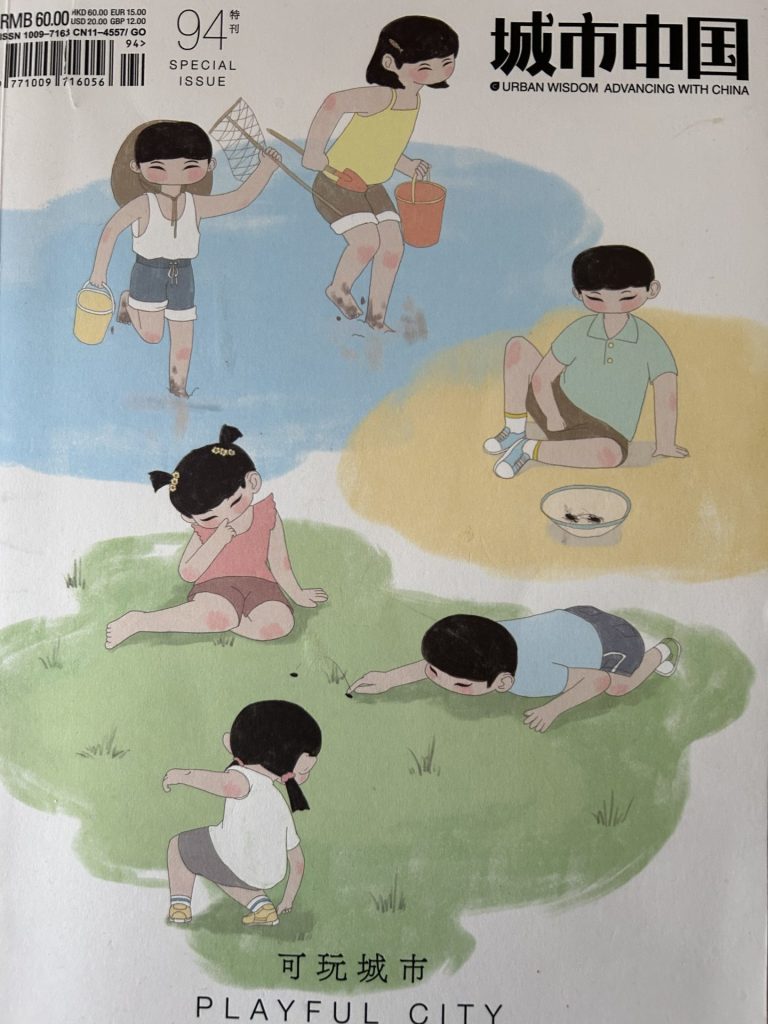

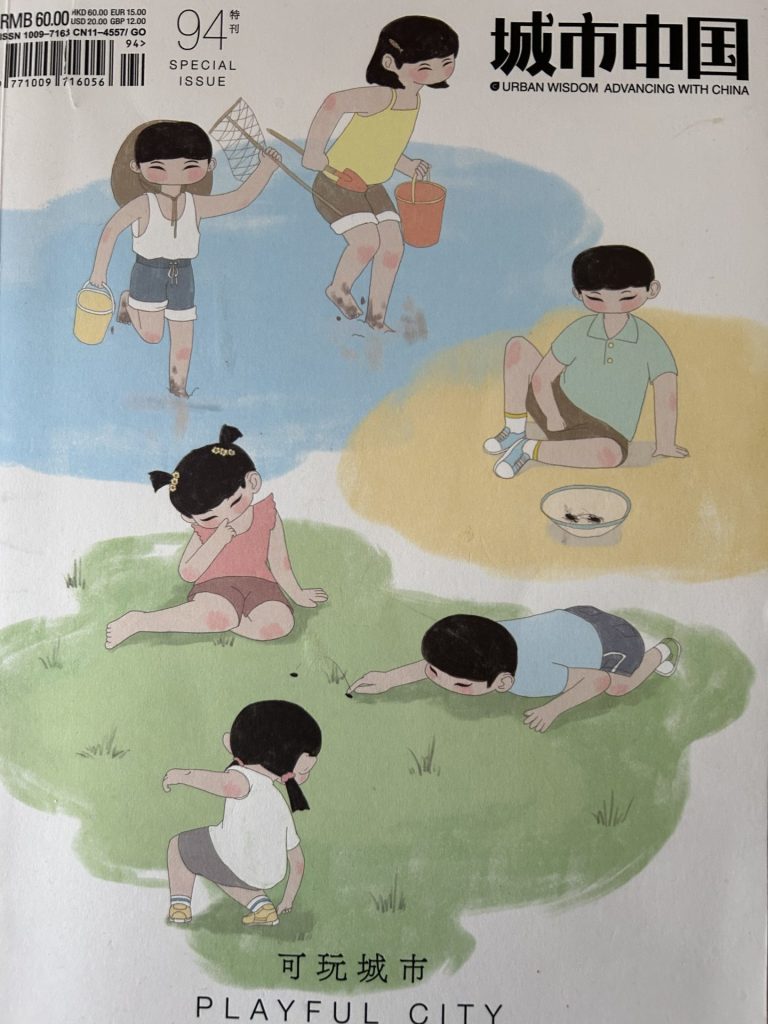

The renowned Shanghai magazine “Urban China” (城市中国) 2023 published a special issue with the title “The Playable City” (可玩城市), in which architects, construction planners, local historians, educators and ecologists collaborated. By interviewing four generations, it tried to find out what role children’s games and toys used to play, how they interacted with nature, the environment and local history. And it asked about the rights of children to grow up and play in a natural and healthy environment.

However, China’s party has other plans for the 253 million 0 to 14-year-olds counted in the latest 2020 census than letting them play carefree. Party leader Xi Jinping wants school lessons to be more politicized and textbooks to be revised in order to raise successors to the revolution. In order to tighten the reins again after 30 years of reforms, the “red genes of the revolution” should already be passed on in kindergarten. “We start with the babies.” 从娃娃抓起. That is a very different kind of game.

Thijs Meijling is the new Head of European Operations at Chinese electric vehicle manufacturer NIO. He joined the company in April 2022 and was previously Head of Europe Commercial Operations. Before joining NIO, he worked for almost five years at Dutch car leasing and fleet management company LeasePlan.

Simon Lichtenberg has been Executive National Board Member at the Danish Chamber of Commerce in China (DCCC) since May. Lichtenberg has been an entrepreneur in China since 1993, focusing on furniture for the emerging middle class. He is based in Shanghai.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Driverless driving – this is now a reality in Ordos in the province of Inner Mongolia, China. After a two-month test run, the local city government has officially approved the operation of five driverless delivery vehicles. Equipped with 5G, artificial intelligence and other advanced technologies, these vehicles have a range of 180 kilometers, can transport up to one ton of cargo and are expected to deliver to 43 stations and points of sale every day. Their maximum speed: 40 kilometers per hour.

The EU Commission is expected to make good on its threat on Monday and impose punitive tariffs on Chinese EV imports. The most interesting question will be: How high will they be? After all, it is certain that tariffs will come.

This marks the EU’s shift away from the ordoliberalism that the Germans, in particular, have upheld in recent decades and towards a strategic industrial policy.

An economic system in which the state only sets the framework and otherwise allows citizens the freedom to compete is, without a doubt, the much more appealing concept. After all, the counter-model is a strong state that constantly intervenes in economic activity and actively participates in it. We Europeans have fared well for many decades with a freely operating middle class.

But times have changed, making other measures necessary: China has emerged as a player that has been feeding its industry with massive subsidies and state aid to such an extent that even healthy top companies can no longer keep up. Its massive overcapacities are wreaking havoc on entire industries around the world. This has already happened in the solar industry and now threatens to do the same to European car manufacturers.

It remains uncertain whether punitive tariffs are the appropriate response and whether they will work at all in light of Chinese predatory pricing. But in this situation, remaining passive, doing nothing and relying on the market to sort things out is more than negligent. Once an industry has been ruined, it will not return for a while. This is also shown by the experience of the solar industry, where the Germans were once the frontrunners, but where developments are now almost exclusively taking place in China.

In today’s issue, Amelie Richter summarizes what will be decided in Brussels on Monday and its potential impact.

The European Commission will likely announce the provisional tariffs on Chinese electric cars early next week. EU circles have suggested Monday, the day after the European elections, as a possible date. However, the Commission has not yet officially confirmed the date.

What else is China doing to prevent the looming measures?

Beijing appears to be still trying to prevent the EU tariffs, which are considered a certainty at this stage – and is using different methods to do so. During his visit to Spain, Trade Minister Wang Wentao warned that “protectionism is not a solution, but a dangerous dead end” and reminded the EU that any measures against Chinese electric cars would mean “a real loss of money.”

During a visit to Greece, Vice Minister of Commerce Ling Ji sharply criticized the EU for the anti-subsidy investigations under the Foreign Subsidies Regulation. If the EU insists on continuing to suppress Chinese companies, “China has the right and sufficient capability to take measures to defend the legitimate interests of its companies,” China Daily, which is regarded as one of the mouthpieces of the leadership in Beijing, quoted Ling as saying.

The same article also emphasizes China’s willingness to engage in dialogue to resolve the trade disputes. In addition, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce reportedly sent a letter to EU Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis asking for a ceasefire in the simmering trade war, as reported by Politico.

What is the backstory?

As part of the Green Deal, the EU has legally committed itself to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030. After difficult negotiations, the member states and the European Parliament agreed to ban the sale of new gasoline-powered cars by 2035, which would make EVs the standard. At the same time, the Chinese economy increased its exports to compensate for weak domestic demand. Chinese electric cars sold well, partly due to their lower prices. The export numbers of Chinese EVs to the EU increased.

Which subsidies does Brussels suspect?

When it announced the investigation in October, the EU Commission listed the state subsidies suspected to be involved: Direct transfers of funds and potential direct transfers of funds or liabilities, i.e., direct financial injections, as well as lost or uncollected state revenue, such as tax breaks. The provision of goods or services by the state for inadequate remuneration is also scrutinized. This includes, for example, the sale of raw and input materials at reduced prices or the provision of labor, some of which is then paid for by the state.

What is still unclear?

The tariffs’ exact amount is still a well-kept secret by the Brussels authority.

What tariff rate do experts expect?

The EU has already imposed a tariff of ten percent on Chinese EVs. The tariffs now decided upon will be added to this. Based on previous anti-subsidy investigations, the Rhodium Group expects a level of 15 to 30 percent, with rates tailored to BYD, Geely and SAIC. The NGO Transport and Environment stated that a 25 percent tariff would make European EVs more competitive against their Chinese rivals and generate additional revenue of between three and six billion euros. Meanwhile, the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) estimates that a tariff of 20 percent would lead to “noticeable trade shifts.”

What consequences will higher tariffs have?

Chinese companies can cushion the impact by selling their products in Europe at a significantly higher price than in China. Furthermore, Chinese brands could circumvent the tariffs by setting up plants in EU countries, as BYD is already planning to do in Hungary. The IfW expects imports of electric cars manufactured in China to drop by 25 percent.

Could this be the start of a trade war?

It is almost certain that Beijing will take retaliatory measures. So far, no Chinese authority has officially announced any measures. However, the state newspaper Global Times has directly threatened various steps through insiders and experts. The focus could be on the European agriculture and aviation industries. Import tariffs on spirits have been mentioned; this could primarily affect cognac from France. Tariffs on cars with larger combustion engines have also been suggested.

Can the tariffs still be stopped?

Not for now, but theoretically in the long term: If the EU Commission proposes permanent tariffs in November, the proposal will be put to the member states for a vote. However, a qualified majority is required to abolish the tariffs: 15 member states representing at least 65 percent of the bloc’s population must vote against the proposal. Alternatively, the EU Commission could also close the investigation and abolish the tariffs – but only if the subsidies under investigation are withdrawn.

The race for the best Chinese AI language model is intensifying. In a recent study, researchers from Beijing’s Tsinghua University identified Baidu’s Ernie Bot 4.0 and the GLM-4 model from start-up Zhipu AI as the country’s best language models (LLMs).

However, the researchers say that both services lag well behind foreign models such as OpenAI’s GPT-4. According to the results published in April, the Western models are clearly superior, particularly with regard to understanding, programming and following instructions – in other words, in all key areas.

Many experts believe that China could be up to two years behind the US in the development of LLMs. However, Tsinghua University suggests that the gap is constantly narrowing. Chinese companies are at a distinct development disadvantage because they do not have access to the latest generation of Western AI chips with which the models are trained. However, China’s catching-up race benefits from the massive competition in its tech sector and the country’s start-up culture.

According to the South China Morning Post, around 200 Chinese companies have already launched their own language models and are constantly improving them. The situation is reminiscent of the early days of the Chinese EV industry. In addition to the traditional car companies, numerous young start-ups entered the market looking to develop advanced vehicles. They had access to extensive funding sources from both state and private investors. These investments allow start-ups to invest in research and development and scale their technologies quickly.

Giants like Baidu, Alibaba and Huawei are all on the AI language model bandwagon. However, there is also a whole range of very young companies that have quickly made a name for themselves. They also have well-known tech companies on board as investors.

The hottest AI start-up is Zhipu AI, with over 800 employees and a 2.5 billion US dollar valuation. A close connection to the renowned Tsinghua University in Beijing, where Zhipu was founded, gives the company access to the country’s talented professionals. Zhipu’s chatbots focus strongly on efficiency in professional and academic contexts and provide clear, precise answers.

Moonshot AI is also experiencing rapid growth. Recently, the company was also valued at around 2.5 billion dollars. Moonshot focuses primarily on the chatbot Kimi, which it has developed specifically for contextualizing information. Other newly crowned AI unicorns with a valuation of over one billion euros include MiniMax and 01.ai, which was founded by well-known AI expert Kai-Fu Lee. These companies are already called the “four new AI tigers” in China.

Companies are engaged in a fierce battle for the best staff and the most talented university graduates, experts in the tech metropolis of Shenzhen say. China is investing heavily in education and research in the field of AI. Many of its universities and research institutes are world leaders in AI research. This leads to the world’s largest number of well-trained AI graduates and specialists.

But they are not only trying to poach the best employees from each other. There is also apparently a lot of poaching going on among foreign competitors. Microsoft has reportedly just asked its China-based cloud computing and AI employees to consider moving abroad. According to the Wall Street Journal, around 700 to 800 employees, mainly Chinese engineers, have been offered the chance to move to countries such as the United States, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. Microsoft is primarily concerned with geopolitical considerations. The US company apparently does not want to do without its Chinese talent in the event of escalating tensions.

June 10-11, 2024

Merics, Workshop (in Brussels): European China Policy Track 1.5 Workshop More

June 10-12, 2024

Trade fair (in Berlin) Taiwan Expo Europe More

June 13, 2024; 10 a.m. (4 p.m. Beijing time)

EU SME Center, Online Workshop: Biotech in China: Assessing Market Opportunities for European SMEs More

June 13-14, 2024

German Chamber of Commerce in China, Insight Tour in Zhaoqing New Area, Guangdong: Hidden Champions in Zhaoqing New Energy Vehicle Industry More

June 18, 2024; 3 p.m. Beijing time

German Chamber of Commerce in China, Policy Briefing (Members free) – in Shenzhen: Immigration & Exit and Entry Policy More

China’s investments in Europe once again declined last year: At 6.8 billion euros, they reached their lowest level since 2010, according to a study published on Thursday by the Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies (Merics) and the Rhodium Group. “Chinese greenfield projects in Europe are a positive development, but the overall low level of investment activity indicates an imbalance in economic relations,” Merics chief economist Max Zenglein said.

According to the study, almost half of Chinese direct investment in Europe flowed to Hungary last year, namely 44 percent. “The Eastern European country therefore attracted more Chinese investment than the three major economies of Germany, France and the UK combined,” Zenglein said.

Chinese companies invested in Hungary primarily in the automotive industry and particularly in electromobility. These accounted for two-thirds (69 percent) of China’s direct investments in Europe last year. The European healthcare industry is also meeting with strong interest from Chinese investors, with a particularly high level of interest in medical devices, which accounted for two-thirds of Chinese investment in this sector between 2021 and 2023.

Hungary has become an important trading partner for China under right-wing Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. China’s President Xi Jinping visited the country in May. Xi declared that relations with Hungary had now developed into an “all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership.” Orbán said that cooperation in nuclear energy was to be intensified, among other things. According to Xi, other projects, such as train connections in Hungary, are also being pursued. rtr

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), only China and Latin American countries have expanded their renewables capacity fast enough in 2022. By 2030, the People’s Republic could expand its capacity by a factor of 2.5 compared to 2022 – this corresponds to 45 percent of the capacity growth required to achieve the global target. The IEA estimates that this would be a sufficiently high contribution. However, China currently also consumes 30 percent of the electricity generated worldwide.

The IEA warns that other countries’ efforts are insufficient. New data shows that even if all countries implement their current plans and targets for the expansion of renewable energies, they would still fall 30 percent short of the global target of tripling capacity by 2030. The IEA states that the national plans would result in a renewable capacity of almost 8,000 gigawatts in 2030 – although tripling renewables and a 1.5-degree pathway would require over 11,000 gigawatts.

The IEA estimates that Europe, the countries of the Asia-Pacific region, the USA and Canada would have to accelerate expansion by several dozen gigawatts per year. In the Middle East, North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa, the rate of expansion would have to double – albeit from a very low level – in order to achieve the national plans. nib

China continues to focus on electric mobility, while investment in Europe is declining. With this argument, the organization Transport and Environment (T&E) is calling for clarity regarding the phase-out of combustion engines. According to the AFP news agency, T&E Managing Director Sebastian Bock said that the automotive industry needs “planning certainty from politicians.” And he warns that the competition from the USA and China is “clearly focussing on e-mobility with investments in the billions.”

A T&E report published on Thursday states that Europe has only secured around a quarter of the investments in electric cars announced worldwide over the past three years. “Investment from foreign manufacturers is needed to secure the location,” warned Bock and, also in light of China’s industrial strength, called for the EU to “urgently develop a strategy” to “keep the supply chains of the cars of the future, which will undoubtedly be electric, in Europe.” flee

After the end of the Cultural Revolution, China’s reforms also introduced personal freedoms, fashion, cosmetics, polite manners and long-lost toys to its ideologically and sartorially uniformed women. European fashion designers such as Pierre Cardin were the first to explore the new market. In the early 1980s, they were followed by Yue-Sai Kan, a Chinese expat living in the USA. Known as the “most famous woman in China,” she taught her compatriots how to behave and how to wear make-up. In 2000, she designed Asian dolls for Chinese girls to pre-empt the import of US glamor girl Barbie 芭比. But unexpectedly for everyone, neither Yue-Sai’s black-haired China Doll nor the blonde Barbie was popular with children in the socialist People’s Republic: It was because of the parents. The dolls were too expensive for them. And girls were supposed to learn – instead of playing with foreign dolls.

My wife, Zhao Yuanhong, who studies the influence of playing on children’s education, was twelve years old in 1966 when she first saw a doll at the height of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. “We had to join the Cultural Revolution as little Red Guards,” she recalled. “Playing in our free time was ostracized as bourgeois, just like learning at school. We followed the example set by the big Red Guards.” They invaded the homes of functionaries and intellectuals, denouncing them as opponents of Mao: “For us children, it was like a big game.”

Yuanhong’s group of adults, students and children tagging along also broke into the ground-floor Beijing courtyard home of economist and philosopher Yu Guangyuan (1915-2013). They rummaged through his rooms and cupboards, tore books from the shelves and searched for incriminating possessions. “We wanted to help the big guys find ‘black’ material.”

Suddenly, a child discovered a small box with a mirror and the petite figure of a dancer. “We called out to Yu: What is that?” “A toy doll,” he replied. “Surely you’ve never seen anything like it? Bring me a smooth surface. Then I’ll show you how it dances.” The scholar placed the figure on the lid of a wooden case. As he approached with the mirror, the doll started to spin. “We bombarded him with questions,” my wife Yuanhong remembers. How does that work? When Yu saw them so amazed, he said: “Did you ever hear in school that magnets attract and repel each other?” The children shook their heads. They tried to make the doll dance. Yu helped patiently and seemed amused. Yuanhong recounts, “We forgot everything around us until a Red Guard came into the room and shouted at Yu: “You reactionary element! What are you doing?”

Twenty years later, my wife sent her memories of the incident to the rehabilitated and now highly respected Science Councilor Yu. He included the anecdote in his book “Persimmon Blossoms in My Garden.” In it, he called on the state and society to return to the cultural and humanistically important significance of playing and toys. He said that researchers and educators should make this their focus. Yu wrote the guidelines for a textbook on the subject.

In 1993, Yu sparked controversy with his view that playing should be depoliticized. He argued that it was one of the essentials in every person’s life to give them the strength, energy and distraction to cope with other needs and goals. “A person should not only learn as long as they live, but also play into old age,” he demanded. As honorary chairman of Beijing’s first international toy fair in 1999, his calligraphed foreword read: “If the mother is the first teacher in a person’s life, then toys are his textbook for life.”

The socialist People’s Republic and its ideologues saw things differently. Like all totalitarian social systems, the leadership placed early childhood education and all play beneath the primacy of politics. The radical Cultural Revolution outlawed playing as bourgeois. Toys were no longer allowed to be sold. One father recounted how he once made a wooden car for his son. He labeled it with Mao slogans so that his son could play without having to worry.

After Mao’s death, everyday life became less tense and market reforms and the opening up of the economy also boosted personal consumption. The population control enforced after 1980 created a demand for toys among the growing generation of only children. Yue-Sai Kan靳羽西, a Chinese expatriate who became famous in the USA thanks to her TV show “Looking East,” recognized this early on. China’s CCTV hired her as a star presenter, who over 300 million Chinese people soon watched. Her guidebooks became bestsellers and she founded a cosmetics chain with 800 boutiques. In 2004, France’s L’Oreal took over her stores.

But her “patriotic” doll series for China’s girls failed. The Yue-Sai Doll 羽西娃娃 presented in Beijing in November 2000 – a black-haired beauty with Asian features and accessories ranging from qipao to red flamenco dance dresses – can now only be found on collector websites.

Even the hyped-up Barbie doll fared no better in China. Knock-offs were sold everywhere at a tenth of the price of the two plastic dolls. Above all, they were culturally alien. China had been cut off from the world and its trends for too long.

Like many US companies, Barbie manufacturer Mattel initially failed to understand what made China’s consumers tick or their relationship with playing. Dozens of studies explain why Barbie flopped in China. One said: “Mattel ignored the fact that parents demanded that their children study hard instead of playing.” Learning was again the highest Confucian virtue of Chinese education. To make matters worse, Barbie was too feminine, had boys on her mind and wore make-up.

Apparently, Mattel had fallen into a “cultural trap.” Instead, educational toys aimed at promoting cognitive skills became successful. Lego was the big winner in China’s market.

Mattel learned the hard way when it tried to force success. The US company converted a large old movie theater in the heart of Shanghai into a six-story Barbie flagship store, the largest in the world, at a cost of 30 million US dollars. Its “House of Barbie,” which opened in 2009, offered everything related to its cult doll with 1,600 products. When Mattel had to close its dream department store in 2011, two years after opening, critics mocked the “nightmare in pink.”

However, the US toy multinational succeeded on a completely different terrain with Barbie. It discovered the People’s Republic early on as a workbench for the production of toys. In 2002, Mattel closed its last US factory in West Kentucky (Murry). From then on, toys worldwide almost always bore the label “made in China.”

Even today, over 70 percent of the toys sold worldwide come from 20 areas of the People’s Republic, primarily from Guangdong. Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Thailand, Vietnam and India are only gradually emerging as manufacturers. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, its impact on the reliability of supply routes and the pressure to reduce dependence on China, a debate about de-risking has also begun in the toy industry.

China itself is returning to its history of playing and traditional toys. “Do China’s kids have their own Barbie?” asked the cultural magazine “The World of Chinese” in late 2023. Toy dolls existed 1,000 years ago and evolved from ritual cult figures.

Toy sellers were already a familiar sight in cities in the 19th century. When foreign colonial powers forcibly seized concession territories, their soldiers and merchants sent home postcards with folklore motifs featuring toy vendors. They offered dolls and animal figurines kneaded from dough, which are still sold at New Year’s markets today.

Most of the more than 100 traditional children’s games have been lost. Researchers and historians are trying to reconstruct and recreate them. “Do you still remember?” asked another medium. Several games, including diabolo 抖空竹 or the shadow puppet game 皮影戏, are China’s cultural heritage and are also on the UNESCO list.

Chinese educators, ecologists and architects are interested in the effects that playing has on early childhood development. The playful connection with nature, with grasses, plants and insects, helps to counteract the barrenness of Chinese cities. In March 2024, 66 percent of the total population already lived in urban centers. For the first time, the new 14th five-year plan includes the government’s task of ensuring child-friendly and play-friendly spaces in cities. Also, for the first time, China is one of 17 countries that want to address this issue as part of UNICEF since 2020,

The renowned Shanghai magazine “Urban China” (城市中国) 2023 published a special issue with the title “The Playable City” (可玩城市), in which architects, construction planners, local historians, educators and ecologists collaborated. By interviewing four generations, it tried to find out what role children’s games and toys used to play, how they interacted with nature, the environment and local history. And it asked about the rights of children to grow up and play in a natural and healthy environment.

However, China’s party has other plans for the 253 million 0 to 14-year-olds counted in the latest 2020 census than letting them play carefree. Party leader Xi Jinping wants school lessons to be more politicized and textbooks to be revised in order to raise successors to the revolution. In order to tighten the reins again after 30 years of reforms, the “red genes of the revolution” should already be passed on in kindergarten. “We start with the babies.” 从娃娃抓起. That is a very different kind of game.

Thijs Meijling is the new Head of European Operations at Chinese electric vehicle manufacturer NIO. He joined the company in April 2022 and was previously Head of Europe Commercial Operations. Before joining NIO, he worked for almost five years at Dutch car leasing and fleet management company LeasePlan.

Simon Lichtenberg has been Executive National Board Member at the Danish Chamber of Commerce in China (DCCC) since May. Lichtenberg has been an entrepreneur in China since 1993, focusing on furniture for the emerging middle class. He is based in Shanghai.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Driverless driving – this is now a reality in Ordos in the province of Inner Mongolia, China. After a two-month test run, the local city government has officially approved the operation of five driverless delivery vehicles. Equipped with 5G, artificial intelligence and other advanced technologies, these vehicles have a range of 180 kilometers, can transport up to one ton of cargo and are expected to deliver to 43 stations and points of sale every day. Their maximum speed: 40 kilometers per hour.