For years, the largest mass migration of modern times has been the travel wave around Chinese New Year. But what is happening in the country this year is unprecedented. Over the next four weeks, a staggering number of nine billion trips are expected, with 7.2 billion by car, writes our China correspondent Joern Petring.

However, this also means that the tourism boom from the Far East hoped for, not least in France, the UK and Switzerland, will not materialize this year either. The Chinese are still reluctant when it comes to traveling to Europe. This is by no means only because Chinese authorities are still not returning many of the passports confiscated during the pandemic. Many Western consulates in China, including the German consulates, are apparently stingy with visas. It seems they have not yet got the message: The pandemic is over!

What is not over, however, are the serious accusations against Volkswagen by human rights organizations. This time, Human Rights Watch criticizes the fact that international car manufacturers are not doing enough to prevent forced labor in their supply chains in the Chinese region of Xinjiang. The accusation is by no means only aimed at German companies, Human Rights Watch emphasizes. However, Volkswagen is the largest foreign player in China due to its massive presence in the country. And this brings with it a special responsibility. In his analysis, Marcel Grzanna laments that the German car manufacturer sees things differently.

Shortly before the Spring Festival, the largest population migration of the year is in full swing in China. Last Friday saw the official start of the Chunyun travel wave, which, according to Chinese state media, is set to break all records this year.

The Chinese Ministry of Transport estimates that a total of around nine billion trips will be made around the New Year, which falls on February 10 this year. This includes all means of transportation, from car travel to train, bus and flights.

The Chunyun refers to a period of around 40 days around the Spring Festival. It is considered the world’s largest annual mass migration. Millions of Chinese people will travel to their hometowns and villages to spend the holiday with their families.

If the forecast is accurate, the number of travelers will likely take on a whole new dimension this year. Last year, shortly after the lifting of zero-Covid, a new record of 4.7 billion trips were registered during the Chunyun. Now, the number is set to double. So travelers will need strong nerves in the coming weeks.

The strong increase can be attributed primarily to the high appetite for travel after the pandemic years. People use the upcoming holidays to catch up on their travels. And many families are likely to be planning several trips in the coming weeks.

For example, if a family of three first travels to visit their grandparents in another province and then the five of them continue to the tropical island of Hainan for a few sunny vacation days, this would result in a total of at least 14 individual trips to and back. Based on this count, it seems entirely possible that 1.4 billion Chinese can make nine billion trips within 40 days.

This expected record number during the Chunyun period is good news for the Chinese tourism industry. The increase in travel is expected to bring an economic boost to various areas of the tourism sector, from hotels and restaurants to tourist attractions.

Of the nine billion trips, about 1.8 billion will be made by rail, road, air and water, while the remaining 7.2 billion trips are expected to be made by car. China Railway announced that around 480 million rail travelers are expected during this travel period, an average of twelve million trips per day. This represents an increase of 37.9 percent compared to the previous year.

Air China, China’s largest airline, announced that it plans to operate 67,691 flights during the 40-day period, with an average of 1,693 flights per day, an increase of 32 percent compared to 2019 and 40.6 percent compared to 2023.

Although the number of overseas travel is likely higher than last year, numbers will again not return to pre-pandemic levels. As the South China Morning Post reports, capacity for international flights in the first quarter of this year is expected to be 30 percent lower than in 2019. According to a report by Chinese search engine operator Baidu, interest in travel to Southeast Asian countries is high once again.

In fact, the city-state of Singapore will probably have to prepare for an avalanche of Chinese visitors. After all, the two sides agreed on a visa-free travel regime in January. The new regulations will come into force on February 9 – the day before Chinese New Year.

Thailand, another popular Chinese tourist destination, was somewhat more cautious. A recent visa-free travel agreement with China will not come into force until March, when the Chunyun is over.

Forced labor remains an issue for the automotive industry. A new investigation by the human rights organization Human Rights Watch (HRW) has found that foreign manufacturers in China are not doing enough to avoid the biggest risks. The accusation: Companies are not adequately tracing back supply chains “to identify and eliminate possible links to Xinjiang.”

Xinjiang is the epitome of state-organized forced labor in China. Official documents and eyewitness testimonies reveal systematic labor programs that channel Uyghur women and men into industries where net pay is far below the minimum wage at best.

The HRW investigation “Asleep at the Wheel” focuses on aluminum car parts. It builds on recent studies, including a study by Hallam Sheffield University last year, which provided evidence of a high probability of human rights violations in the industry’s value chains.

Some manufacturers are said to have yielded to political pressure from the government in Beijing. Car manufacturers apply weaker human rights and responsible sourcing standards in their joint ventures in the People’s Republic than in other parts of the world, HRW concludes. “Consumers should as a result have little confidence that they are purchasing and driving vehicles free from links to abuses in Xinjiang,” the authors write.

In the middle of the hazard zone is Volkswagen. The German manufacturer is represented in Xinjiang by a joint venture with the state-owned producer SAIC. The company repeatedly emphasizes that it takes reports of possible human rights violations very seriously, but admits to HRW that it still has “blind spots” regarding the origin of the aluminum in its cars.

More than 15 percent of the aluminum produced in China, or 9 percent of the global supply, comes from the region. The volume in Xinjiang has increased from around one million tons in 2010 to six million tons in 2022. According to the International Aluminum Institute (IAI), car manufacturers accounted for about 18 percent of total global aluminum consumption in 2021. The IAI predicts that the industry’s demand for aluminum will double between 2019 and 2050. China, which produced almost 60 percent of the global supply in 2022, is one of the major beneficiaries.

However, only a fraction of high-grade alloys, aluminum sheets or foils are produced in Xinjiang directly. Instead, “unalloyed” ingots from Xinjiang are further processed in other Chinese provinces. There, the trail of their origin and possible involvement in the forced labor system usually goes cold.

Unnamed employees of the automotive industry and experts acknowledge to HRW “that there were steps they could take to push Chinese suppliers towards more supply chain transparency.” Car companies could, for example, require their partners to disclose supply chains to better quantify and thus reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Car manufacturers and their first or second-tier suppliers could also source more aluminum directly from smelters outside Xinjiang.

HRW took a closer look at Toyota, Tesla, BYD, General Motors and Volkswagen. Behind closed doors, Volkswagen sees itself as a projection screen for NGOs that use the company as a scapegoat. However, HRW emphasizes that Volkswagen, like the four other manufacturers, was chosen due to its size, significant production and sales presence in China, and geographical diversity.

With reference to the anonymous industry sources, HRW reports about threats of retaliation by the Chinese government. Companies are being prevented from talking to their China-based suppliers and joint ventures about their possible ties to forced labor in Xinjiang.

According to the report, the government is criminalizing investigations into allegations of human rights violations and forced labor. In April 2023, it also passed an expanded counterintelligence law that could extend criminal prosecution of foreign companies researching local markets and business partners.

HRW reviewed the procurement policies of the five companies in their joint ventures and compared them with the manufacturers’ public statements – for example, on their efforts to eliminate any involvement in forced labor. Volkswagen emphasizes that it “assumes responsibility under the UN Guiding Principles to use its leverage over its Chinese joint ventures to address the risk of human rights abuses.”

Yet the company ducks away by hiding behind legal positions. Volkswagen told HRW that legal responsibility only existed where there was “decisive influence” on the joint venture – social sustainability flying blind, so to speak. HRW disagrees. In Germany, a company has decisive influence over a subsidiary when the latter manufactures and sells the same products or provides the same services as the parent company.

In a statement to Table.Media, Volkswagen states that only companies belonging to the group in affiliated companies are part of Volkswagen AG’s own business operations. “SAIC-Volkswagen (SVW) and SAIC-Volkswagen Xinjiang are not part of Volkswagen AG’s own business operations as defined Act in the German Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains (LkSG, see section 2 (6) sentence 3),” the group argues. For this reason, the company sees no business relationship (see section 15 AktG) between Volkswagen AG and SVW or SVW Xinjiang.

However, SAIC-Volkswagen manufactures and sells cars for the Chinese market under the Volkswagen brand. Trying to convince the public that these cars are not part of the Volkswagen AG division will be a monumental undertaking in the years to come.

Feb 2-7, 2024

HLS China Law Association (conference, on site): 2024 Harvard China Law Symposium – Longevity: Building Resilient Bridges More

Feb. 6, 2024; 8 p.m., Hamburg

Elbphilharmonie Hamburg: The Grand Chinese New Year Concert with the China National Traditional Orchestra (CNTO) and pipa player and artistic director Zhao Cong, More

Feb. 8, 2024; 2 p.m. CET (9 p.m. CST)

Department of East Asian Language and Civilizations, Zoom Lecture: Mingwei Song – Fear of Seeing: A Poetics of Chinese Science Fiction More

Feb. 8, 2024; 3:30 p.m. CET (10:30 p.m. CST)

Center for Strategic and International Studies, Webcast: What is Next for Taiwan? Capital Cable #87 More

At the first monthly meeting of the new year, the Politburo was still unable to agree on a date for the important Third Plenum of the Central Committee, which will set the course for economic policy over the next five years. This means that the economic course for 2024 has still not been set. According to the traditional timetable of the CP apparatus, the plenum should have been held in October 2023. Now, however, it could even be postponed until after the National People’s Congress in March. This is significant because the People’s Congress sets the economic policy for the current year, including the growth target. And it is usually based on the resolutions of the Third Plenum.

“The unexplained delay in holding the much-anticipated third plenum will further undermine already low business and consumer confidence,” write analysts at Trivium China. “That will make it more difficult for the economy to consolidate its nascent recovery.” German companies would welcome to see a prioritization of incentives and reforms to boost the economy, said Jens Hildebrandt, Executive Director of the German Chamber of Commerce (AHK) in Beijing. “A third plenum that delivers clear signals on how China plans to address its structural economic challenges and shape its future would be greatly appreciated.”

According to official figures, China’s economy grew by 5.2 percent in 2023. For this year, economists at the World Bank expect growth of just 4.5 percent.

The confusion surrounding the Third Plenum is an example of how the typical CP standards and structures are increasingly softening under state and party leader Xi Jinping. With 205 functionaries, the Central Committee is the core of the CP and serves for a period of five years between two party congresses. As a rule, it convenes at least once a year, with each of these seven plenums being loosely assigned an area of importance – the third being the economy. At the Third Plenum in 2013, Xi agreed to a reform program and a greater role for the market, which he has still not implemented. Control over the economy, on the other hand, is increasing.

Xi is known for taking control over all important decisions and pushing certain issues. At Wednesday’s meeting, he called for promoting “disruptive innovation,” integrating technology into the industry, and increasing the resilience of Chinese supply chains. Instead of scheduling the Third Plenum, the Politburo tellingly dealt with a report on the education campaign on the “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” and new CP regulations on discipline control. ck

By choosing the priest Peter Wu Yishun, the government in Beijing and the Vatican have agreed on a third bishop in just one week. Wu will take over the diocese of Shaowu. The Holy See Press Office announced the appointment on Wednesday after the bishop’s consecration had taken place. It is part of the provisional agreement between the Vatican and the People’s Republic of China. An earlier announcement confirmed that new bishops for Zhengzhou and Weifang had already been appointed.

“The provisional agreement on the appointment of bishops signed by the two parties has been well implemented,” spokesperson Wang Wenbin told a regular briefing, adding that his country wanted to continuously improve its “bilateral relations with the Vatican in the spirit of mutual respect and equal dialogue.”

For decades, China and the Holy See had been at odds, particularly over the appointment of Chinese bishops. Officially, the two sides do not maintain diplomatic relations. However, there has been a rapprochement since Francis became Pope. In 2022, they renewed an agreement that gives both sides a say in the appointment of bishops in China. flee

A court in Hong Kong found four people guilty of rioting during the 2019 pro-democracy protests on Thursday. The verdict comes after eight others had already pleaded guilty to charges over the incident when hundreds of protesters besieged Hong Kong’s Legislative Council building on July 1, 2019. Hong Kong’s district court sets a maximum of seven years in prison for rioting.

Although the court acquitted two reporters who were also charged with rioting, they were found guilty of “entering or staying in the precincts of the chamber” of the government building. Another defendant wept in the courtroom after the verdict was read out. The eight individuals who had previously pleaded guilty to sedition include the former president of the Hong Kong University Students’ Union and two pro-democracy activists. cyb/rtr

The consumer goods group Henkel is expanding its hair care business with an acquisition in China. Henkel is acquiring the Vidal Sassoon brand in the People’s Republic from its competitor Procter & Gamble, the German company announced on Thursday. The Vidal Sassoon portfolio generally offers more expensive shampoos and conditioners and thus serves the premium segment.

The company generated a turnover of more than 200 million euros in the 2022/2023 fiscal year. According to a Henkel spokesperson, the acquisition price is around 300 million dollars. The acquisition strengthens Henkel’s consumer division, which bundles the detergent and personal care product businesses. cyb/rtr

Luke Luhas been appointed Citi Country Officer (CCO) and Head of Banking in China at Citigroup. Lu joined Citi in Shanghai in 2002 and served most recently as head of the Chinese corporate client business. He succeeds Christine Lam, who is retiring.

Alan Wylie supports the Merics management as assistant and handles accounting and human resources. He previously worked as a language teacher in Berlin, France and Austria and as a translator, proofreader and lecturer in business communication in the UK.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know heads@table.media!

When the United States was still the sole nuclear power in 1947, guerrilla leader Mao Zedong referred to the US disrespectfully as a paper tiger in an interview with correspondent Anna Louise Strong: frightening on the outside, but weak and defeatable on the inside. Mao’s comparison became popular among revolutionaries all over the world.

The Chinese counterpart to the American paper tiger is the straw dragon. Guangzhou cartoonist Kuang Biao recently drew a picture of a dragon with a gruesome head sitting on a body made of straw. A fitting symbolic animal for the New Year 2024, which begins on February 10. It is the year of the wooden dragon, which only appears every 60 years. It is based on the cycle of the twelve zodiac signs, which are each assigned one of five elements: metal, wood, water, fire and earth.

As the only mythical creature of the twelve calendar animals, an ancient symbol of China’s imperial power and also a bringer of good luck, dragons should actually be a favorite motif of China’s satirists – if only the censors would let them. However, the Beijing leadership, which fears that 2024 will be a year of significant challenges to its power, does not want an impotent dragon that is more illusion than reality. No newspaper is allowed to print such a dragon. Images posted online by other illustrators who have mounted their dragon heads on rotting wood have also been censored.

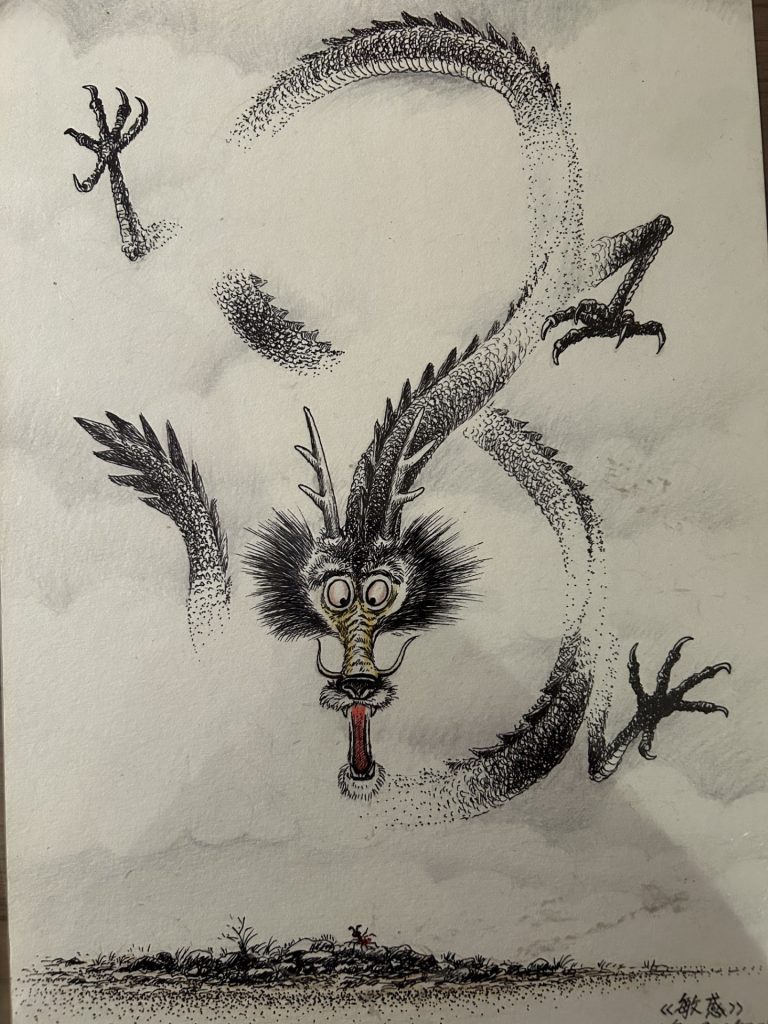

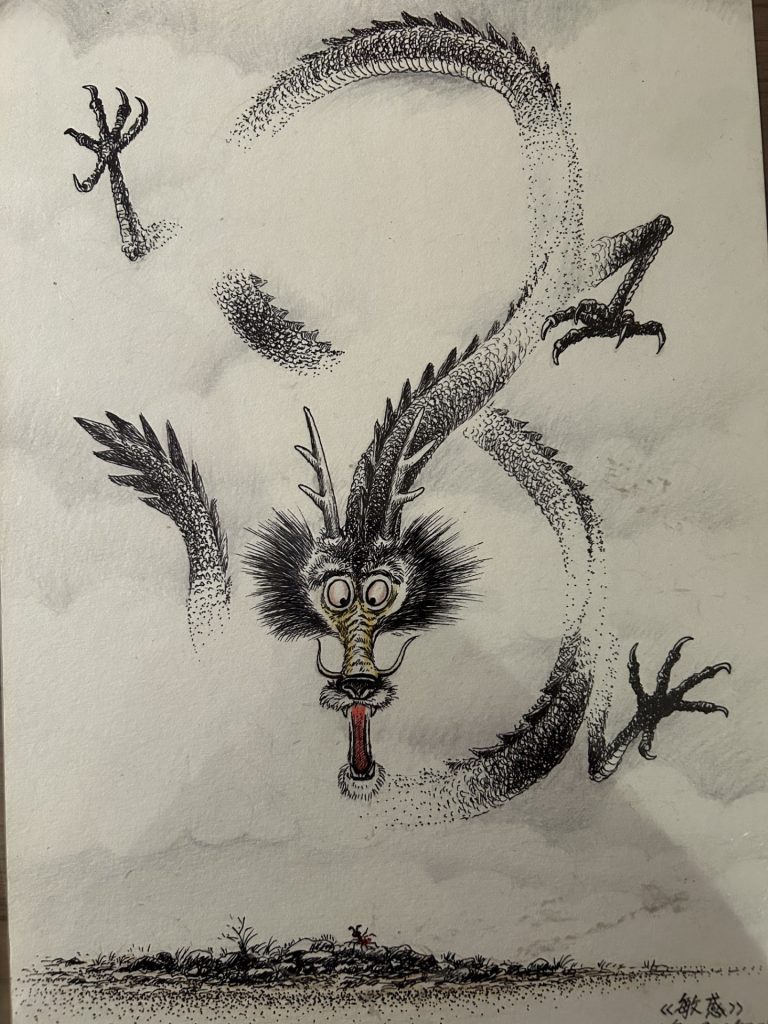

Kuang’s straw dragon is not allowed out of its online cage. He already experienced this in 2012 – the year of the (water) dragon. He drew a monster that panicked at the sight of a small ant, like the proverbial elephant at the sight of a mouse. The meaningful characters for “Sensitive” are written under the drawing. It was drawn at a time when Beijing saw a great threat from a minority of regime critics.

“Smelling allusions everywhere is deeply rooted in our political culture,” China’s grand master of satire, Hua Junwu, who was brutally persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, once told me. Rehabilitated in honor afterward, he hoped that such days were over. He was proven wrong in late 1979 when Beijing’s leadership suddenly outlawed the “Democracy Wall” 西单民主墙, which it had originally initiated and supported as a sign of reform. The demands for more democracy on its posters went too far for the leadership.

Hua spontaneously drew a dragon made up of the two characters for democracy 民主, with an official running away from it. Hua alluded to an ancient Chinese legend and the proverb 叶公好龙 (Mr. Ye loves dragons), which tells of a passionate collector of dragon paintings who runs away when a real dragon visits him. Hua had two students shout: “Comrade, why are you running away when you talk about democracy so much?” He shouts back: “I didn’t know it was really coming.”

Shortly after the drawing appeared in a Guangzhou newspaper under the title of the proverb, “well-meaning Beijing powers” advised Hua to stop publishing it. It is absent from his ten-volume edition.

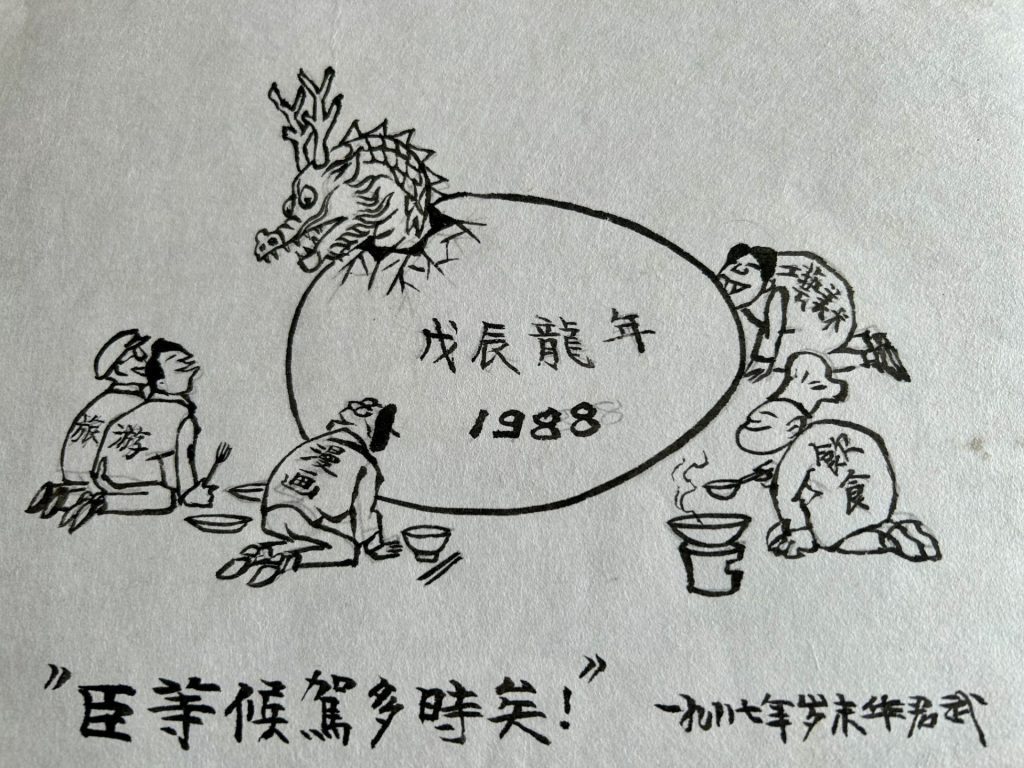

In protest against censorship, Hue drew a picture of a group of hedgehogs singing: “We call ourselves caricaturists, we all wear spikes, but we don’t sting.” For the New Year of the (Earth) Dragon in 1988, he drew a dragon hatching from its egg as criticism of China’s over-commercialization of the family festival. Groups of profiteers kneel before him in reverence: “We, Your Majesty’s subjects, have waited a long time for you.” Alongside the tourism, catering and arts and crafts industries, cartoonists are also present. Hua painted himself wearing a cap.

The People’s Republic has always had an ambivalent relationship with the dragon. For a long time, it ostracized it as a feudal symbolic animal. Today, it has been rehabilitated. Full of subliminal patriotism, the Chinese can now call themselves “descendants of the dragon,” especially their head of state Xi Jinping. On 16 November 2017, he and his wife accompanied Mr and Mrs Trump on a stroll through the Imperial Palace, whose Hall of Supreme Harmony 故宫 太和殿 is adorned with 13,000 dragons. In front of the cameras of CCTV, he told Trump: “We are the original people, black hair, yellow skin, inherited onwards. We call ourselves the descendants of the dragon” “我们这些人也是原来的人。黑头发、黄皮肤,传承下来,我们叫龙的传人.”

Commenting on its party leader’s statement, the People’s Daily wrote that dragon culture had “made a great contribution to the culture of mankind as an important part of the culture of the Far East.” The dragon was a “revered totem of the Chinese nation 崇拜的图腾 and a symbol of joy, peace, freedom and happiness for the people,” while dragons are the embodiment of “evil in every form” in the West.

Since the turn of the millennium, “we have been discussing this diametrically different understanding of the dragon,” wrote linguist Huang Ji 黄佶 from Shanghai’s Huadong Pedagogical University. In his 2022 paper, he demanded that the Chinese word for dragon 龙 should be translated as either “long” or “loong” based on the Chinese pronunciation, but no longer as “dragon,” as this word would create false associations and misunderstandings.

Huang Ji, who has been researching the perception of the dragon myth for 20 years, revealed that China’s Olympic Committee, in preparation for the 2008 Summer Games, decided not to choose the dragon as the mascot of the Games despite a majority public vote. On November 11, 2005, it decided: “Dragons are understood differently in East and West. That is why they are not suitable as mascots.”

Around the year 2000, the People’s Republic started its global expansion. Beijing’s leadership was worried about its global reputation. China’s relationship with the dragon triggered patriotic fervor. The opinion of the Shanghai cultural researcher Wu Youfu 吴友富 was particularly provocative. Shanghai’s morning newspaper reported in December 2006 that Professor Wu had called for the “reconstruction of a new national image brand” 重新建构中国国家形象品牌” that would not tarnish China’s reputation as a peacefully rising world power. Instead of the dragon, which was seen as an aggressive monster in the West, Beijing would need a positive image and a national symbol that stands for harmony.

Such words prompted angry emails from nationalists. They condemned Wu’s “total Westernization.” For thousands of years, the “sons and daughters of the Chinese nation have proudly called themselves descendants of the dragon.”

Since the 13th century, there have been mentions of China’s dragons – sometimes also called snakes – in other countries, first by explorers such as Marco Polo or early missionaries. The dragon was increasingly seen as a monster, as people from Europe and America to the Middle East feared it, wrote Huang Ji. As a symbol of domination, it served as a means of “demonizing China” and was associated with “Yellow Peril.” The reputation of dragons even reached the Socialist Consultative Conference. From March 2015, there were three consecutive years of unsuccessful motions to correct false foreign translations of the word 龙. The word was no longer supposed to be called “dragon” in Western languages, but as the Chinese phonetic word “loong.” A large project 中华思想文化术语传播工程 initiated by several ministries under the leadership of the State Council in 2014 to develop new translations for specific Chinese terms in foreign languages agreed on 400 proposals in 2017. A new translation for “dragon” was not among them, Huang Ji lamented.

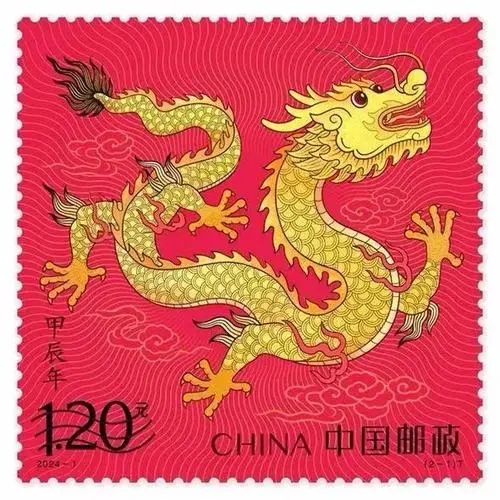

The dragon remains a touchy subject. In 2012, stamp designer Chen Shaohua experienced this first-hand when he created a postage design of a scary monster for the Year of the Water Dragon, which allegedly left Millions of Chinese terrified. The online outcry was so intense that the news agency Xinhua called the stamp a trigger of a “national debate,” reflecting the dispute over the self-perception of the People’s Republic. As an emerging superpower, shouldn’t it rather focus on soft power and promote itself as a “friendly dragon”? In 2014, during his visit to France, Xi Jinping announced – avoiding the word dragon – that China was a lion, but a “peaceful, amicable and civilized lion.”

Beijing has obviously learned its lesson. At least when it comes to stamp diplomacy. For the Year of the Dragon 2024, stamp motifs with playful dragons were issued. The only trouble came from the United States, whose postal service also printed New Year stamps for the Year of the Dragon. Overseas Chinese were outraged and felt offended. They said the Chinese dragon “Made in the USA” was a “bizarre monster, a “mixture of ox and monkey.” 像牛又像猴 Beijing’s party newspaper “Global Times” took up the criticism of its compatriots and polemicized against the USA.

To keep everything tame in the Year of the Wooden Dragon 2024, Beijing’s cyberspace authorities announced a month of stricter internet controls in late January. The authorities want to bring calm to the internet during the Spring Festival with a “special campaign” and nip any form of online agitation and disruption of public order, rumors and fake news in the bud. Allusive cartoons included.

Artisans across China are preparing for the festivities surrounding the upcoming Year of the Dragon. This Chongqing man is making figures from palm leaves, a centuries-old art in Southwest China. All twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac are crafted in these workshops. But none is as intricate as the dragon.

For years, the largest mass migration of modern times has been the travel wave around Chinese New Year. But what is happening in the country this year is unprecedented. Over the next four weeks, a staggering number of nine billion trips are expected, with 7.2 billion by car, writes our China correspondent Joern Petring.

However, this also means that the tourism boom from the Far East hoped for, not least in France, the UK and Switzerland, will not materialize this year either. The Chinese are still reluctant when it comes to traveling to Europe. This is by no means only because Chinese authorities are still not returning many of the passports confiscated during the pandemic. Many Western consulates in China, including the German consulates, are apparently stingy with visas. It seems they have not yet got the message: The pandemic is over!

What is not over, however, are the serious accusations against Volkswagen by human rights organizations. This time, Human Rights Watch criticizes the fact that international car manufacturers are not doing enough to prevent forced labor in their supply chains in the Chinese region of Xinjiang. The accusation is by no means only aimed at German companies, Human Rights Watch emphasizes. However, Volkswagen is the largest foreign player in China due to its massive presence in the country. And this brings with it a special responsibility. In his analysis, Marcel Grzanna laments that the German car manufacturer sees things differently.

Shortly before the Spring Festival, the largest population migration of the year is in full swing in China. Last Friday saw the official start of the Chunyun travel wave, which, according to Chinese state media, is set to break all records this year.

The Chinese Ministry of Transport estimates that a total of around nine billion trips will be made around the New Year, which falls on February 10 this year. This includes all means of transportation, from car travel to train, bus and flights.

The Chunyun refers to a period of around 40 days around the Spring Festival. It is considered the world’s largest annual mass migration. Millions of Chinese people will travel to their hometowns and villages to spend the holiday with their families.

If the forecast is accurate, the number of travelers will likely take on a whole new dimension this year. Last year, shortly after the lifting of zero-Covid, a new record of 4.7 billion trips were registered during the Chunyun. Now, the number is set to double. So travelers will need strong nerves in the coming weeks.

The strong increase can be attributed primarily to the high appetite for travel after the pandemic years. People use the upcoming holidays to catch up on their travels. And many families are likely to be planning several trips in the coming weeks.

For example, if a family of three first travels to visit their grandparents in another province and then the five of them continue to the tropical island of Hainan for a few sunny vacation days, this would result in a total of at least 14 individual trips to and back. Based on this count, it seems entirely possible that 1.4 billion Chinese can make nine billion trips within 40 days.

This expected record number during the Chunyun period is good news for the Chinese tourism industry. The increase in travel is expected to bring an economic boost to various areas of the tourism sector, from hotels and restaurants to tourist attractions.

Of the nine billion trips, about 1.8 billion will be made by rail, road, air and water, while the remaining 7.2 billion trips are expected to be made by car. China Railway announced that around 480 million rail travelers are expected during this travel period, an average of twelve million trips per day. This represents an increase of 37.9 percent compared to the previous year.

Air China, China’s largest airline, announced that it plans to operate 67,691 flights during the 40-day period, with an average of 1,693 flights per day, an increase of 32 percent compared to 2019 and 40.6 percent compared to 2023.

Although the number of overseas travel is likely higher than last year, numbers will again not return to pre-pandemic levels. As the South China Morning Post reports, capacity for international flights in the first quarter of this year is expected to be 30 percent lower than in 2019. According to a report by Chinese search engine operator Baidu, interest in travel to Southeast Asian countries is high once again.

In fact, the city-state of Singapore will probably have to prepare for an avalanche of Chinese visitors. After all, the two sides agreed on a visa-free travel regime in January. The new regulations will come into force on February 9 – the day before Chinese New Year.

Thailand, another popular Chinese tourist destination, was somewhat more cautious. A recent visa-free travel agreement with China will not come into force until March, when the Chunyun is over.

Forced labor remains an issue for the automotive industry. A new investigation by the human rights organization Human Rights Watch (HRW) has found that foreign manufacturers in China are not doing enough to avoid the biggest risks. The accusation: Companies are not adequately tracing back supply chains “to identify and eliminate possible links to Xinjiang.”

Xinjiang is the epitome of state-organized forced labor in China. Official documents and eyewitness testimonies reveal systematic labor programs that channel Uyghur women and men into industries where net pay is far below the minimum wage at best.

The HRW investigation “Asleep at the Wheel” focuses on aluminum car parts. It builds on recent studies, including a study by Hallam Sheffield University last year, which provided evidence of a high probability of human rights violations in the industry’s value chains.

Some manufacturers are said to have yielded to political pressure from the government in Beijing. Car manufacturers apply weaker human rights and responsible sourcing standards in their joint ventures in the People’s Republic than in other parts of the world, HRW concludes. “Consumers should as a result have little confidence that they are purchasing and driving vehicles free from links to abuses in Xinjiang,” the authors write.

In the middle of the hazard zone is Volkswagen. The German manufacturer is represented in Xinjiang by a joint venture with the state-owned producer SAIC. The company repeatedly emphasizes that it takes reports of possible human rights violations very seriously, but admits to HRW that it still has “blind spots” regarding the origin of the aluminum in its cars.

More than 15 percent of the aluminum produced in China, or 9 percent of the global supply, comes from the region. The volume in Xinjiang has increased from around one million tons in 2010 to six million tons in 2022. According to the International Aluminum Institute (IAI), car manufacturers accounted for about 18 percent of total global aluminum consumption in 2021. The IAI predicts that the industry’s demand for aluminum will double between 2019 and 2050. China, which produced almost 60 percent of the global supply in 2022, is one of the major beneficiaries.

However, only a fraction of high-grade alloys, aluminum sheets or foils are produced in Xinjiang directly. Instead, “unalloyed” ingots from Xinjiang are further processed in other Chinese provinces. There, the trail of their origin and possible involvement in the forced labor system usually goes cold.

Unnamed employees of the automotive industry and experts acknowledge to HRW “that there were steps they could take to push Chinese suppliers towards more supply chain transparency.” Car companies could, for example, require their partners to disclose supply chains to better quantify and thus reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Car manufacturers and their first or second-tier suppliers could also source more aluminum directly from smelters outside Xinjiang.

HRW took a closer look at Toyota, Tesla, BYD, General Motors and Volkswagen. Behind closed doors, Volkswagen sees itself as a projection screen for NGOs that use the company as a scapegoat. However, HRW emphasizes that Volkswagen, like the four other manufacturers, was chosen due to its size, significant production and sales presence in China, and geographical diversity.

With reference to the anonymous industry sources, HRW reports about threats of retaliation by the Chinese government. Companies are being prevented from talking to their China-based suppliers and joint ventures about their possible ties to forced labor in Xinjiang.

According to the report, the government is criminalizing investigations into allegations of human rights violations and forced labor. In April 2023, it also passed an expanded counterintelligence law that could extend criminal prosecution of foreign companies researching local markets and business partners.

HRW reviewed the procurement policies of the five companies in their joint ventures and compared them with the manufacturers’ public statements – for example, on their efforts to eliminate any involvement in forced labor. Volkswagen emphasizes that it “assumes responsibility under the UN Guiding Principles to use its leverage over its Chinese joint ventures to address the risk of human rights abuses.”

Yet the company ducks away by hiding behind legal positions. Volkswagen told HRW that legal responsibility only existed where there was “decisive influence” on the joint venture – social sustainability flying blind, so to speak. HRW disagrees. In Germany, a company has decisive influence over a subsidiary when the latter manufactures and sells the same products or provides the same services as the parent company.

In a statement to Table.Media, Volkswagen states that only companies belonging to the group in affiliated companies are part of Volkswagen AG’s own business operations. “SAIC-Volkswagen (SVW) and SAIC-Volkswagen Xinjiang are not part of Volkswagen AG’s own business operations as defined Act in the German Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains (LkSG, see section 2 (6) sentence 3),” the group argues. For this reason, the company sees no business relationship (see section 15 AktG) between Volkswagen AG and SVW or SVW Xinjiang.

However, SAIC-Volkswagen manufactures and sells cars for the Chinese market under the Volkswagen brand. Trying to convince the public that these cars are not part of the Volkswagen AG division will be a monumental undertaking in the years to come.

Feb 2-7, 2024

HLS China Law Association (conference, on site): 2024 Harvard China Law Symposium – Longevity: Building Resilient Bridges More

Feb. 6, 2024; 8 p.m., Hamburg

Elbphilharmonie Hamburg: The Grand Chinese New Year Concert with the China National Traditional Orchestra (CNTO) and pipa player and artistic director Zhao Cong, More

Feb. 8, 2024; 2 p.m. CET (9 p.m. CST)

Department of East Asian Language and Civilizations, Zoom Lecture: Mingwei Song – Fear of Seeing: A Poetics of Chinese Science Fiction More

Feb. 8, 2024; 3:30 p.m. CET (10:30 p.m. CST)

Center for Strategic and International Studies, Webcast: What is Next for Taiwan? Capital Cable #87 More

At the first monthly meeting of the new year, the Politburo was still unable to agree on a date for the important Third Plenum of the Central Committee, which will set the course for economic policy over the next five years. This means that the economic course for 2024 has still not been set. According to the traditional timetable of the CP apparatus, the plenum should have been held in October 2023. Now, however, it could even be postponed until after the National People’s Congress in March. This is significant because the People’s Congress sets the economic policy for the current year, including the growth target. And it is usually based on the resolutions of the Third Plenum.

“The unexplained delay in holding the much-anticipated third plenum will further undermine already low business and consumer confidence,” write analysts at Trivium China. “That will make it more difficult for the economy to consolidate its nascent recovery.” German companies would welcome to see a prioritization of incentives and reforms to boost the economy, said Jens Hildebrandt, Executive Director of the German Chamber of Commerce (AHK) in Beijing. “A third plenum that delivers clear signals on how China plans to address its structural economic challenges and shape its future would be greatly appreciated.”

According to official figures, China’s economy grew by 5.2 percent in 2023. For this year, economists at the World Bank expect growth of just 4.5 percent.

The confusion surrounding the Third Plenum is an example of how the typical CP standards and structures are increasingly softening under state and party leader Xi Jinping. With 205 functionaries, the Central Committee is the core of the CP and serves for a period of five years between two party congresses. As a rule, it convenes at least once a year, with each of these seven plenums being loosely assigned an area of importance – the third being the economy. At the Third Plenum in 2013, Xi agreed to a reform program and a greater role for the market, which he has still not implemented. Control over the economy, on the other hand, is increasing.

Xi is known for taking control over all important decisions and pushing certain issues. At Wednesday’s meeting, he called for promoting “disruptive innovation,” integrating technology into the industry, and increasing the resilience of Chinese supply chains. Instead of scheduling the Third Plenum, the Politburo tellingly dealt with a report on the education campaign on the “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” and new CP regulations on discipline control. ck

By choosing the priest Peter Wu Yishun, the government in Beijing and the Vatican have agreed on a third bishop in just one week. Wu will take over the diocese of Shaowu. The Holy See Press Office announced the appointment on Wednesday after the bishop’s consecration had taken place. It is part of the provisional agreement between the Vatican and the People’s Republic of China. An earlier announcement confirmed that new bishops for Zhengzhou and Weifang had already been appointed.

“The provisional agreement on the appointment of bishops signed by the two parties has been well implemented,” spokesperson Wang Wenbin told a regular briefing, adding that his country wanted to continuously improve its “bilateral relations with the Vatican in the spirit of mutual respect and equal dialogue.”

For decades, China and the Holy See had been at odds, particularly over the appointment of Chinese bishops. Officially, the two sides do not maintain diplomatic relations. However, there has been a rapprochement since Francis became Pope. In 2022, they renewed an agreement that gives both sides a say in the appointment of bishops in China. flee

A court in Hong Kong found four people guilty of rioting during the 2019 pro-democracy protests on Thursday. The verdict comes after eight others had already pleaded guilty to charges over the incident when hundreds of protesters besieged Hong Kong’s Legislative Council building on July 1, 2019. Hong Kong’s district court sets a maximum of seven years in prison for rioting.

Although the court acquitted two reporters who were also charged with rioting, they were found guilty of “entering or staying in the precincts of the chamber” of the government building. Another defendant wept in the courtroom after the verdict was read out. The eight individuals who had previously pleaded guilty to sedition include the former president of the Hong Kong University Students’ Union and two pro-democracy activists. cyb/rtr

The consumer goods group Henkel is expanding its hair care business with an acquisition in China. Henkel is acquiring the Vidal Sassoon brand in the People’s Republic from its competitor Procter & Gamble, the German company announced on Thursday. The Vidal Sassoon portfolio generally offers more expensive shampoos and conditioners and thus serves the premium segment.

The company generated a turnover of more than 200 million euros in the 2022/2023 fiscal year. According to a Henkel spokesperson, the acquisition price is around 300 million dollars. The acquisition strengthens Henkel’s consumer division, which bundles the detergent and personal care product businesses. cyb/rtr

Luke Luhas been appointed Citi Country Officer (CCO) and Head of Banking in China at Citigroup. Lu joined Citi in Shanghai in 2002 and served most recently as head of the Chinese corporate client business. He succeeds Christine Lam, who is retiring.

Alan Wylie supports the Merics management as assistant and handles accounting and human resources. He previously worked as a language teacher in Berlin, France and Austria and as a translator, proofreader and lecturer in business communication in the UK.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know heads@table.media!

When the United States was still the sole nuclear power in 1947, guerrilla leader Mao Zedong referred to the US disrespectfully as a paper tiger in an interview with correspondent Anna Louise Strong: frightening on the outside, but weak and defeatable on the inside. Mao’s comparison became popular among revolutionaries all over the world.

The Chinese counterpart to the American paper tiger is the straw dragon. Guangzhou cartoonist Kuang Biao recently drew a picture of a dragon with a gruesome head sitting on a body made of straw. A fitting symbolic animal for the New Year 2024, which begins on February 10. It is the year of the wooden dragon, which only appears every 60 years. It is based on the cycle of the twelve zodiac signs, which are each assigned one of five elements: metal, wood, water, fire and earth.

As the only mythical creature of the twelve calendar animals, an ancient symbol of China’s imperial power and also a bringer of good luck, dragons should actually be a favorite motif of China’s satirists – if only the censors would let them. However, the Beijing leadership, which fears that 2024 will be a year of significant challenges to its power, does not want an impotent dragon that is more illusion than reality. No newspaper is allowed to print such a dragon. Images posted online by other illustrators who have mounted their dragon heads on rotting wood have also been censored.

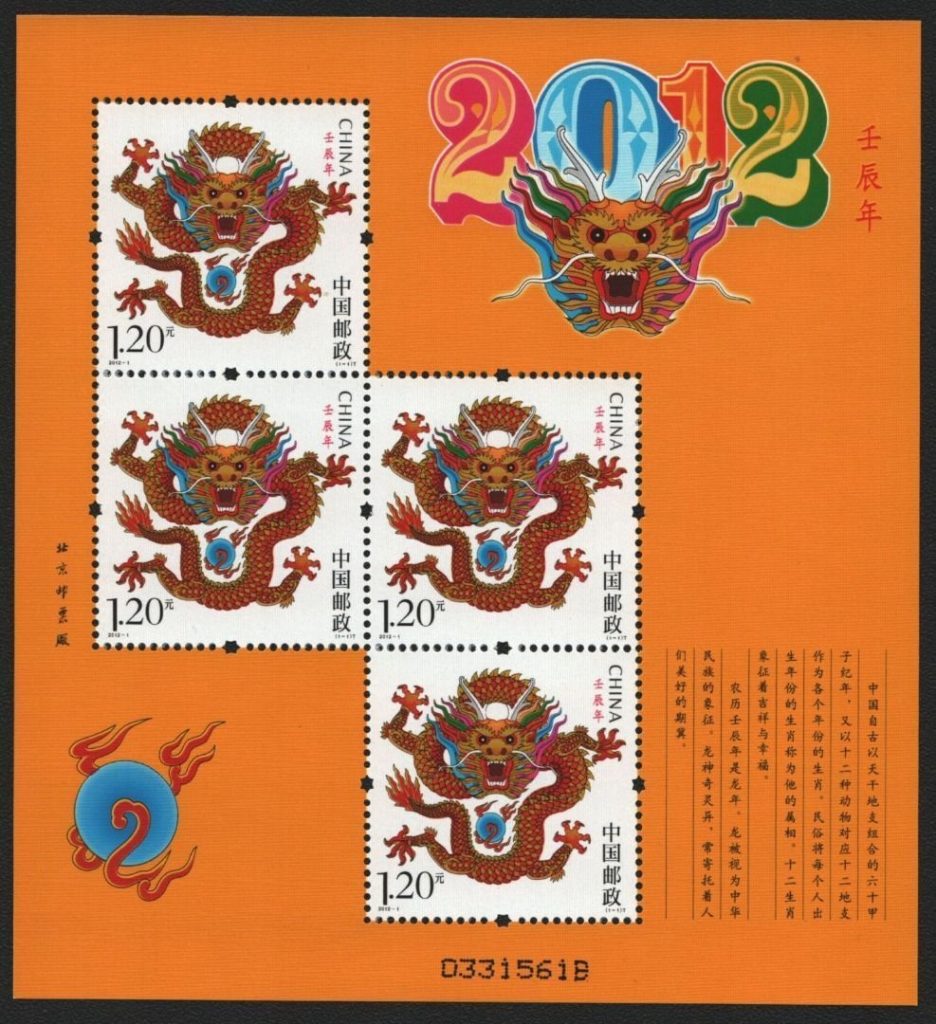

Kuang’s straw dragon is not allowed out of its online cage. He already experienced this in 2012 – the year of the (water) dragon. He drew a monster that panicked at the sight of a small ant, like the proverbial elephant at the sight of a mouse. The meaningful characters for “Sensitive” are written under the drawing. It was drawn at a time when Beijing saw a great threat from a minority of regime critics.

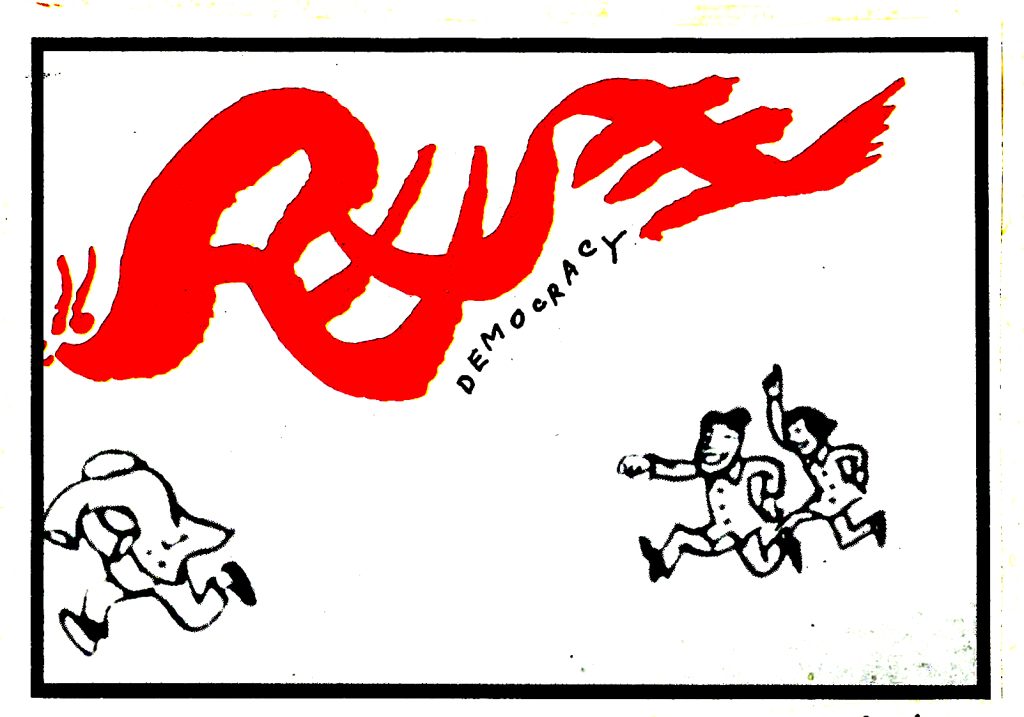

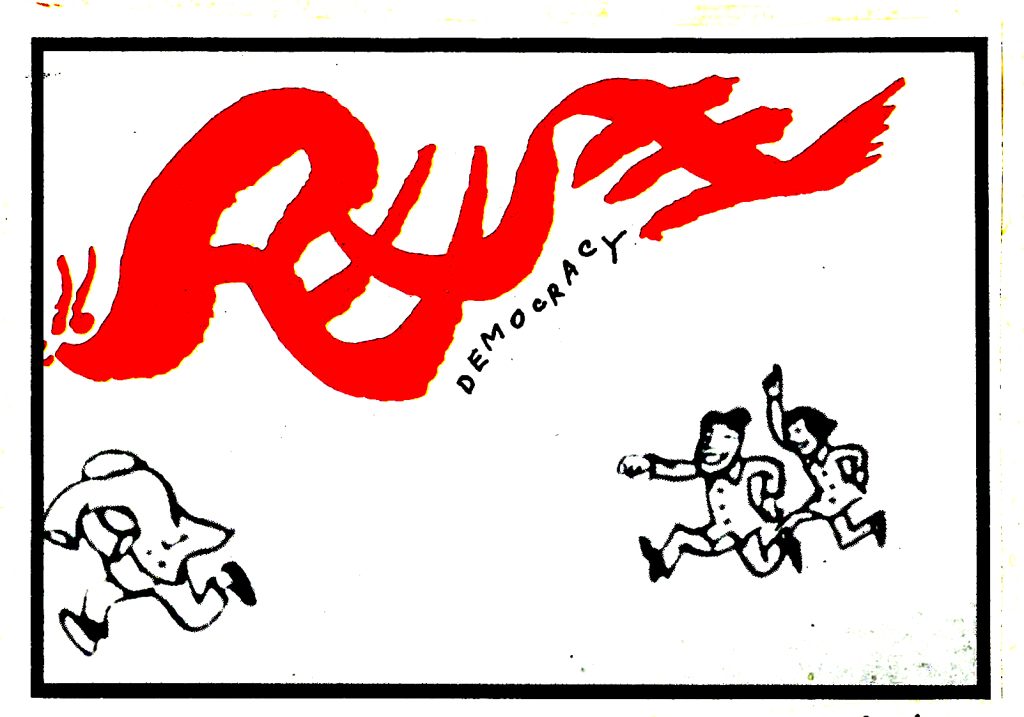

“Smelling allusions everywhere is deeply rooted in our political culture,” China’s grand master of satire, Hua Junwu, who was brutally persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, once told me. Rehabilitated in honor afterward, he hoped that such days were over. He was proven wrong in late 1979 when Beijing’s leadership suddenly outlawed the “Democracy Wall” 西单民主墙, which it had originally initiated and supported as a sign of reform. The demands for more democracy on its posters went too far for the leadership.

Hua spontaneously drew a dragon made up of the two characters for democracy 民主, with an official running away from it. Hua alluded to an ancient Chinese legend and the proverb 叶公好龙 (Mr. Ye loves dragons), which tells of a passionate collector of dragon paintings who runs away when a real dragon visits him. Hua had two students shout: “Comrade, why are you running away when you talk about democracy so much?” He shouts back: “I didn’t know it was really coming.”

Shortly after the drawing appeared in a Guangzhou newspaper under the title of the proverb, “well-meaning Beijing powers” advised Hua to stop publishing it. It is absent from his ten-volume edition.

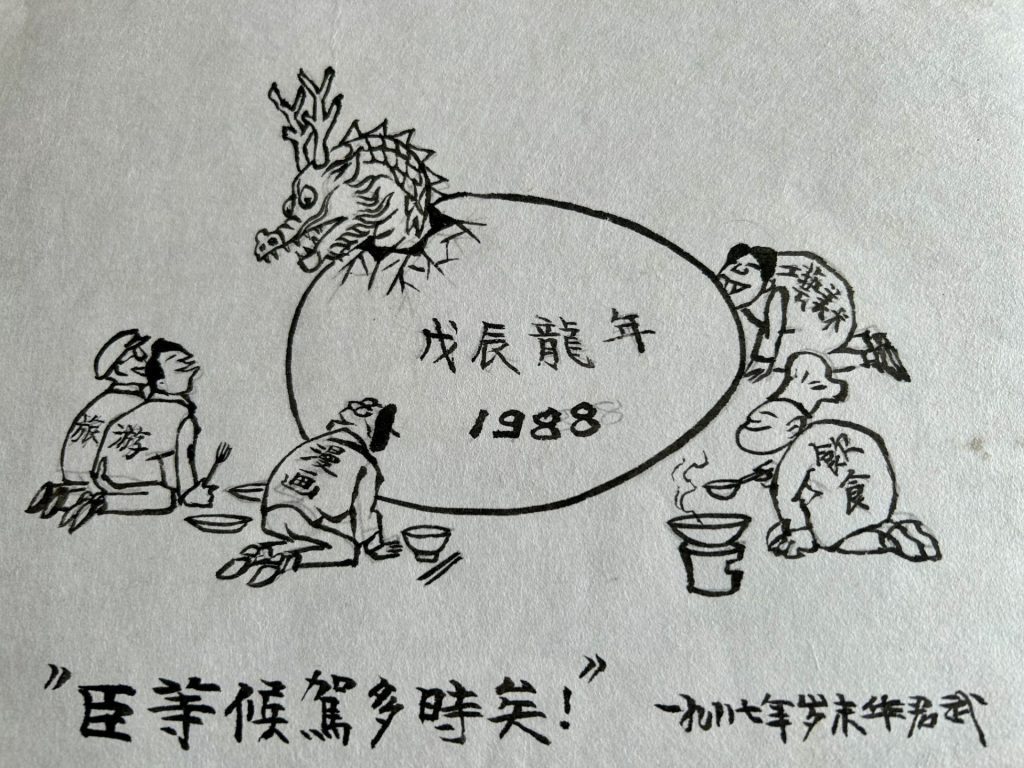

In protest against censorship, Hue drew a picture of a group of hedgehogs singing: “We call ourselves caricaturists, we all wear spikes, but we don’t sting.” For the New Year of the (Earth) Dragon in 1988, he drew a dragon hatching from its egg as criticism of China’s over-commercialization of the family festival. Groups of profiteers kneel before him in reverence: “We, Your Majesty’s subjects, have waited a long time for you.” Alongside the tourism, catering and arts and crafts industries, cartoonists are also present. Hua painted himself wearing a cap.

The People’s Republic has always had an ambivalent relationship with the dragon. For a long time, it ostracized it as a feudal symbolic animal. Today, it has been rehabilitated. Full of subliminal patriotism, the Chinese can now call themselves “descendants of the dragon,” especially their head of state Xi Jinping. On 16 November 2017, he and his wife accompanied Mr and Mrs Trump on a stroll through the Imperial Palace, whose Hall of Supreme Harmony 故宫 太和殿 is adorned with 13,000 dragons. In front of the cameras of CCTV, he told Trump: “We are the original people, black hair, yellow skin, inherited onwards. We call ourselves the descendants of the dragon” “我们这些人也是原来的人。黑头发、黄皮肤,传承下来,我们叫龙的传人.”

Commenting on its party leader’s statement, the People’s Daily wrote that dragon culture had “made a great contribution to the culture of mankind as an important part of the culture of the Far East.” The dragon was a “revered totem of the Chinese nation 崇拜的图腾 and a symbol of joy, peace, freedom and happiness for the people,” while dragons are the embodiment of “evil in every form” in the West.

Since the turn of the millennium, “we have been discussing this diametrically different understanding of the dragon,” wrote linguist Huang Ji 黄佶 from Shanghai’s Huadong Pedagogical University. In his 2022 paper, he demanded that the Chinese word for dragon 龙 should be translated as either “long” or “loong” based on the Chinese pronunciation, but no longer as “dragon,” as this word would create false associations and misunderstandings.

Huang Ji, who has been researching the perception of the dragon myth for 20 years, revealed that China’s Olympic Committee, in preparation for the 2008 Summer Games, decided not to choose the dragon as the mascot of the Games despite a majority public vote. On November 11, 2005, it decided: “Dragons are understood differently in East and West. That is why they are not suitable as mascots.”

Around the year 2000, the People’s Republic started its global expansion. Beijing’s leadership was worried about its global reputation. China’s relationship with the dragon triggered patriotic fervor. The opinion of the Shanghai cultural researcher Wu Youfu 吴友富 was particularly provocative. Shanghai’s morning newspaper reported in December 2006 that Professor Wu had called for the “reconstruction of a new national image brand” 重新建构中国国家形象品牌” that would not tarnish China’s reputation as a peacefully rising world power. Instead of the dragon, which was seen as an aggressive monster in the West, Beijing would need a positive image and a national symbol that stands for harmony.

Such words prompted angry emails from nationalists. They condemned Wu’s “total Westernization.” For thousands of years, the “sons and daughters of the Chinese nation have proudly called themselves descendants of the dragon.”

Since the 13th century, there have been mentions of China’s dragons – sometimes also called snakes – in other countries, first by explorers such as Marco Polo or early missionaries. The dragon was increasingly seen as a monster, as people from Europe and America to the Middle East feared it, wrote Huang Ji. As a symbol of domination, it served as a means of “demonizing China” and was associated with “Yellow Peril.” The reputation of dragons even reached the Socialist Consultative Conference. From March 2015, there were three consecutive years of unsuccessful motions to correct false foreign translations of the word 龙. The word was no longer supposed to be called “dragon” in Western languages, but as the Chinese phonetic word “loong.” A large project 中华思想文化术语传播工程 initiated by several ministries under the leadership of the State Council in 2014 to develop new translations for specific Chinese terms in foreign languages agreed on 400 proposals in 2017. A new translation for “dragon” was not among them, Huang Ji lamented.

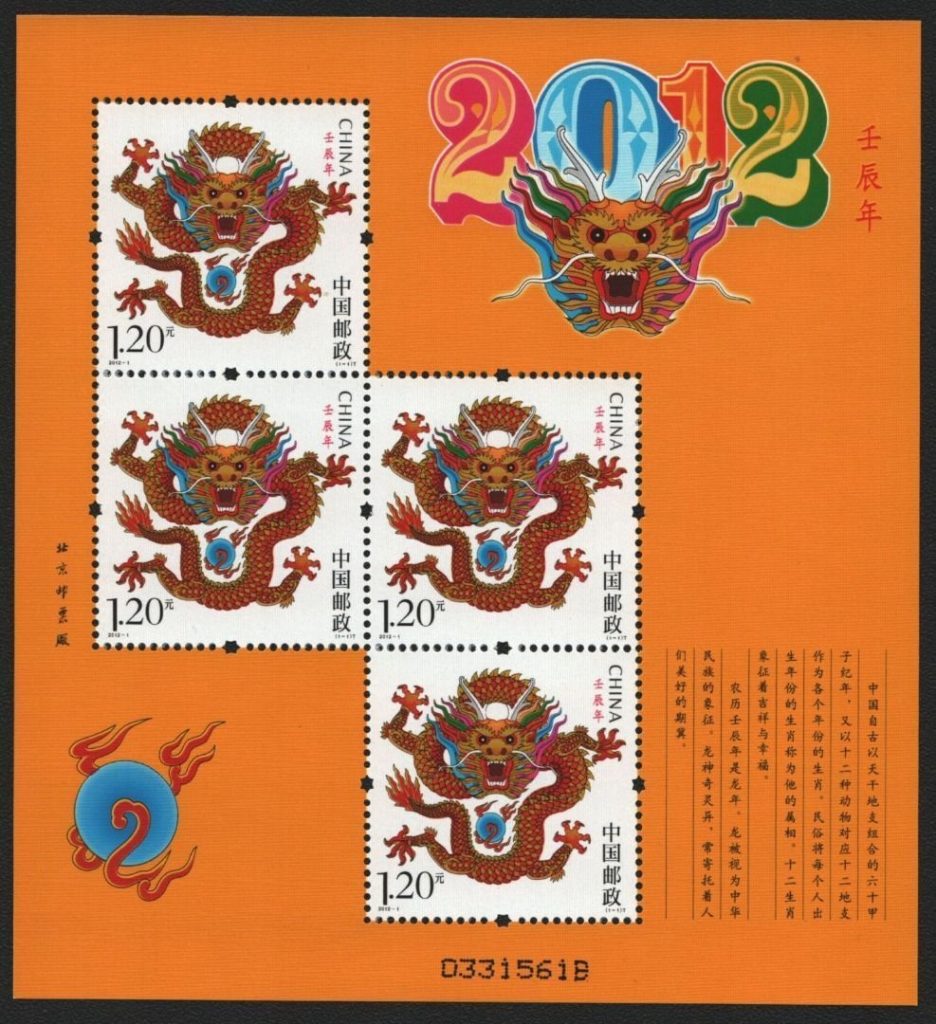

The dragon remains a touchy subject. In 2012, stamp designer Chen Shaohua experienced this first-hand when he created a postage design of a scary monster for the Year of the Water Dragon, which allegedly left Millions of Chinese terrified. The online outcry was so intense that the news agency Xinhua called the stamp a trigger of a “national debate,” reflecting the dispute over the self-perception of the People’s Republic. As an emerging superpower, shouldn’t it rather focus on soft power and promote itself as a “friendly dragon”? In 2014, during his visit to France, Xi Jinping announced – avoiding the word dragon – that China was a lion, but a “peaceful, amicable and civilized lion.”

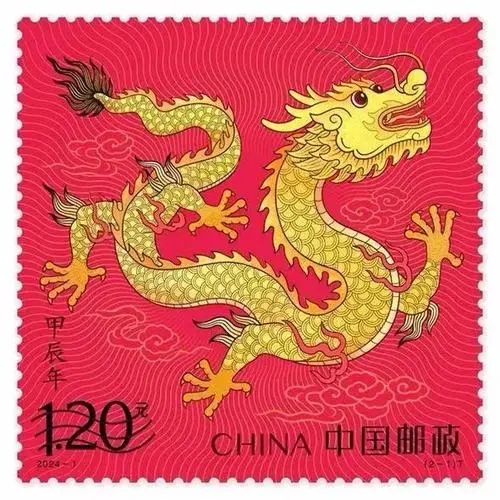

Beijing has obviously learned its lesson. At least when it comes to stamp diplomacy. For the Year of the Dragon 2024, stamp motifs with playful dragons were issued. The only trouble came from the United States, whose postal service also printed New Year stamps for the Year of the Dragon. Overseas Chinese were outraged and felt offended. They said the Chinese dragon “Made in the USA” was a “bizarre monster, a “mixture of ox and monkey.” 像牛又像猴 Beijing’s party newspaper “Global Times” took up the criticism of its compatriots and polemicized against the USA.

To keep everything tame in the Year of the Wooden Dragon 2024, Beijing’s cyberspace authorities announced a month of stricter internet controls in late January. The authorities want to bring calm to the internet during the Spring Festival with a “special campaign” and nip any form of online agitation and disruption of public order, rumors and fake news in the bud. Allusive cartoons included.

Artisans across China are preparing for the festivities surrounding the upcoming Year of the Dragon. This Chongqing man is making figures from palm leaves, a centuries-old art in Southwest China. All twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac are crafted in these workshops. But none is as intricate as the dragon.