It has been years of struggle: removing Huawei from Germany’s networks – yes or no? Security concerns and fears of espionage and sabotage spoke in favor of a clean-up. However, network operators protested loudly and refused to talk about a restructuring. Even the government was divided. It is now clear that the German government will ban components from Chinese manufacturers Huawei and ZTE from its 5G mobile networks – but this is essentially a sham solution.

In fact, the components have already been replaced in many parts of the core network. In other areas, the deadlines have been significantly extended. Yet nothing is being done for particularly critical infrastructures, such as government buildings in Berlin, Bundeswehr sites and NATO facilities. In their analysis, Michael Radunski and Felix Lee provide an overview of what has been decided and what criticism has been leveled at the decision.

China’s successful e-commerce platforms differ fundamentally from old-fashioned online shopping in Europe. Over here, people still go to Amazon, where they search for products in a nicely structured way: Categorized and filtered, relevant products appear on one page. Totally practical, completely emotionless. On the other hand, Chinese e-commerce apps such as Temu and Pinduoduo focus entirely on gamification. And Pinduoduo uses group buying to turn shopping into an experience with friends – if many people join in, the price drops.

The user experience also increasingly influences Western providers and their underlying business models. Amazon announced this month that it will increasingly use dealer networks from China, similar to Temu – without middlemen and the company’s own logistics centers. While Temu is in the spotlight for its competitive prices, there are growing security concerns about Pinduoduo. Fabian Peltsch provides an insight into the world of e-commerce giants.

The years-long dispute in Germany over how to deal with mobile communications components from China is coming to an end. The German government and network operators have reached a compromise on how to handle technology from Chinese companies. The result: not everything has to go. Nancy Faeser (SPD) explained this in Berlin on Thursday. “We have now reached a clear and strict agreement with the telecommunications companies,” said the Federal Minister of the Interior. Corresponding contracts will now be signed this week.

The fear is that companies such as Huawei and ZTE could use the technology for espionage or even commit sabotage on behalf of the Chinese government due to their close ties to the Communist Party. German mobile network operators, on the other hand, value Chinese technology for being inexpensive and efficient.

Specifically, the compromise agreed on the following points, all of which have been under discussion for some time:

Essentially, this compromise is a sham solution because it cleverly avoids having to make critical decisions.

Many mobile network operators had warned against excluding Chinese providers – especially Huawei. They were concerned that the quality of the mobile network could deteriorate. Germany’s digitalization is already behind that of many other developed and emerging countries. An analysis by telecommunications consultancy Strand Consult found that Huawei was responsible for almost 60 percent of Germany’s 5G network in 2022.

In response to the current compromise, Huawei once again dismissed all security concerns. The management of Huawei Germany stated that it has always been reliable and can boast an excellent security track record. “There is still no verifiable evidence or plausible scenarios that Huawei’s technology would pose a security risk in any form,” a Huawei spokesperson wrote in a statement.

And Huawei assures: “We will continue to work constructively and openly with our partners and customers to jointly achieve improvements and progress in the area of cybersecurity and to accelerate the development of mobile networks and digitalization in Germany.”

The reason for the slow decision-making process are the differing views in the German government:

Security authorities have been warning for some time about China’s attempts to penetrate critical infrastructures around the world. Security circles claim that China has already managed to gain a strong foothold in critical infrastructures in some countries. And 5G networks are of paramount importance.

Human rights groups have strongly condemned the decision. The spokesperson for the Tibet Initiative Germany speaks of a “poor compromise.” He said that instead of quickly removing Chinese components from the entire network, a minimal compromise had now been agreed. Only the software will be replaced in the antenna and access networks. It is doubtful whether this solution can be implemented at all, as Huawei and other Chinese manufacturers would have to willingly open up their hardware to new software.

But the decision also sends a fatal signal to Tibetans and other people persecuted by Beijing: “For these groups in particular, such a decision sows new doubts whether Germany has the will to provide a safe life in exile.” Collaboration: Felix Lee

Driven by the success of Temu and Shein, Amazon plans to source more goods directly from China. Without middlemen and without warehousing in Amazon’s own logistics centers, the aim is to have them reach the buyer within nine to eleven days. On average, these no-name products cost under 20 US dollars – conditions that Temu now offers in 50 countries and with which it is slowly stealing Amazon’s thunder.

According to Amazon, the number of Chinese sellers on the platform has already increased by more than 20 percent in 2023 compared to the previous year – partly because fees have been reduced for sellers who offer clothing for less than 20 US dollars. The modernization of the largest Western e-commerce provider is in full swing.

Like TikTok, Temu is also backed by a Chinese tech giant: Pinduoduo Holdings (PDD), a Nasdaq-listed company based in Shanghai. It was founded in 2015 by Colin Huang, a highly respected entrepreneur in China who previously worked as a software developer and product manager for companies including Google. A son of two factory workers from Hangzhou, he was recognized early on as a mathematical prodigy. He studied computer science at Zhejiang University and went to the USA in 2002, where he earned a master’s degree in computer science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. An impressed professor subsequently wrote him letters of recommendation for all leading US tech companies. Huang ended up working for Google, whose entry into the Chinese market he helped prepare.

After leaving Google, Huang founded several start-ups, including an online gaming company and an e-commerce website specializing in consumer electronics. The founding legend of Pinduoduo is that a middle ear infection put Huang out of action for more than a year.

During this time, the then 33-year-old realized that the two largest tech companies in China, Alibaba and Tencent, “didn’t really understand how the other company made money.” He then combined their and his areas of specialization, namely online games and e-commerce, to form Pinduoduo.

Huang’s company has long since caught up with the top dogs. In May, the company reported that it had tripled its net profit in the first three months of the fiscal year by 246 percent to around 3.6 billion euros compared to last year. The revenue of Alibaba and the other major e-commerce provider, JD.com, grew by less than 10 percent.

Pinduoduo generates most of its revenue, around 88 percent, from advertising. In 2023, two-thirds of revenue came from sellers who wanted to place their product offers more prominently on the website and app. A model that Huang learned from Google.

Pinduoduo has occupied niches in several respects. Firstly, the company has taken gamification to the next level. Countless addictive online games promise discounts. One market observer spoke of “dollar store meets Candy Crush.” The idea is for users to visit the app not so much with the intention of making a purchase, but to pass the time.

Secondly, Pinduoduo has set new benchmarks in China with the idea of group purchases. Users can receive discounts of up to 90 percent if they either initiate a group purchase themselves or join an existing group purchase.

Pinduoduo, which means “do more together” in Chinese, has turned the traditional retail model on its head – from supply-oriented to demand-oriented. Suppliers can reduce costs by responding directly to fluctuations in demand, for example. Shorter product development times allow small manufacturers and retailers to compete with larger suppliers.

In China, group purchasing helped skyrocket Pinduoduo’s user numbers through the word-of-mouth advertising inherent to the model. The app became a hit in WeChat groups in particular, which Tencent, soon to become one of Pinduoduo’s largest shareholders, supported with technology and funding. Pinduoduo also anticipated the changing purchasing behavior of the Chinese middle class. While companies like Alibaba focused more and more on premium products, Huang concentrated on less wealthy rural areas and “third-tier” cities with fewer than three million inhabitants from the outset. When the slowing economy forced people to save money, Pinduoduo was there at the right time with cheap offers.

Just like Amazon started out selling books, Huang initially focused on fresh fruit and vegetables straight from producers. China’s fresh fruit market grew rapidly in 2015, although less than three percent was sold online at the time. Unlike Temu, Pinduoduo still sells food on a large scale today. And this is not the only difference in the successful model. Instead of relying on word of mouth through group purchases, Temu relies primarily on targeted advertising campaigns abroad. In the United States, the company even ran TV ads during the Superbowl, the country’s biggest sporting event.

Like Temu in the West, Pinduoduo faced early criticism in China due to the poor quality of its products. Like TikTok’s parent company ByteDance, Pinduoduo is also increasingly in the spotlight overseas due to security concerns. Last year, the Pinduoduo app was blocked from the Google Play Store outside of China after cybersecurity experts discovered that it was infected with malware. Washington and Brussels discuss restrictions and bans on Temu.

Chen Lei, Co-Chief Executive and Chairman of PDD Holdings, explains that Temu’s global expansion is still at an early stage with many uncertainties. A collaboration with Amazon comes at just the right time. In addition to more Chinese retailers on Amazon, the US company has also launched its own Amazon store on Pinduoduo. This gives Amazon, whose market share in China is less than one percent, access to millions of Chinese consumers. And Pinduoduo may soon also be able to access Amazon’s global network of suppliers and logistics providers for Temu.

July 16, 2024; 4 p.m. Beijing time

German Chamber of Commerce, GCC Knowledge Hub: Explanation of Personal Income Tax Planning and Equity Structure for Foreign Enterprises More

July 16, 2024; 10 p.m. CEST (July 17, 4 a.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, book presentation and discussion: A New Cold War: Conversation with Sir Robin Niblett More

July 17, 2024; 10 p.m. CEST (July 18, 3 a.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, Webcast: The Importance of National Resilience: Implications for Taiwan More

July 18, 2024; 10 a.m. CEST (4 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Dezan Shira & Associates, Webinar: Hong Kong 2024: Unlocking Investment & Business Opportunities More

July 18, 2024; 10:30 a.m. CEST (4:30 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Sino-German Center at Frankfurt School, webinar with Joerg Wuttke and Prof. Klaus Muehlhahn: Results of The 3rd Plenum: Progress Ahead for The Economy? More

July 18, 2024; 3 p.m. CEST (9 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, Webcast: How does the Taiwan Public View the U.S. and China? More

July 19, 2024; 3 p.m. CEST (9 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, Webcast: A Fireside Discussion with U.S. Ambassador to China Nicholas Burns More

July 22, 2024; 3 p.m. CEST (9 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, Webcast: China’s Third Plenum: A Plan for Renewed Reform? More

July 22, 2024; 11 a.m. CEST (4 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

GIGA Hamburg, Seminar (Hybrid): Navigating Post-Pandemic Fieldwork in China: Challenges, Adaptations, and Insights More

The Chinese Foreign Ministry has protested on Thursday against the “illegal and inappropriate” actions of a Japanese ship that entered Chinese waters. Foreign Ministry spokesman Lin Jian announced at the regular press conference in Beijing that China will take action against all those who enter Chinese territory without permission. He added that Japan is expected not to allow such an incident to occur again.

The Japanese destroyer “Suzutsuki” entered Chinese waters off Zhejiang province on July 4, and China was planning to conduct naval exercises at the same time. The Kyodo news agency, citing diplomatic sources, reported that the Suzutsuki was monitoring Chinese missile exercises in the East China Sea north of Taiwan.

The authorities of Zhejiang had imposed a no-sailing zone in the area the day before so that the Chinese military could carry out the live-fire exercise. The Chinese government suspects a “deliberate provocation” behind the destroyer incident, which may have gathered security-related information. Despite direct warnings, the destroyer reportedly remained within twelve nautical miles of the coast of Zhejiang for around 20 minutes. The Japanese side spoke of a technical fault. The Ministry of Defense announced an investigation.

The incident further strains the already tense relations between China and Japan. The leadership in Tokyo is currently making great efforts to forge closer ties with other partners in the region. Just a few days ago, it signed a defense agreement with the Philippines. It will allow both countries to send troops to each other for joint military exercises. Cooperation with South Korea and the USA is also being intensified. All of this displeases the leadership in Beijing. rad

According to the human rights organization Human Rights Watch (HRW), aluminum products from Xinjiang should be included in the planned EU register of goods to assess the risk of forced labor.

The register is part of the EU regulation on products of forced labor. For this to have a concrete impact on state-imposed forced labor in China, the inclusion of Xinjiang and the aluminum sector in the database is crucial, HRW explained in a statement. The organization recommends a total of 17 sectors from clothing to toy production in the Xinjiang region that should be included in the EU register.

The EU would thus follow the US, which has added aluminum to the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) legislation, as Alejandro Mayorkas, US Secretary of Homeland Security, explained in an interview with the US think tank CSIS. Accordingly, the UFLPA also covers seafood and PVC.

The planned EU regulation is intended to prevent consumers from buying goods that have been produced using forced labor. The online database will publish specific geographical areas and sectors where there is a risk of forced labor, including by the state. The database should be available from 2026, with the regulation coming into force at the end of 2027. ari

The office of the Commissioner of the Chinese Foreign Ministry in Hong Kong sharply criticized the USA on Thursday. It called on the US government to end its “persecution fantasies.” The public statement further said that Washington should also stop interfering in Hong Kong’s affairs.

The reason for the outrage is that US President Joe Biden extended the “emergency status” over Hong Kong a few hours earlier. Biden cited “recent actions” by China in his justification: “The situation with respect to Hong Kong, including recent actions taken by the People’s Republic of China to fundamentally undermine Hong Kong’s autonomy, continues to pose an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States.”

This is the fourth extension of an order issued in 2020 that revokes Hong Kong’s status as a preferred trading partner. Former US President Donald Trump first declared the “national emergency.” It is a response to the National Security Law that Beijing imposed on Hong Kong after months of anti-government protests since 2019.

The Chinese response added that the US should “immediately stop its self-humiliating political act” or face the “collective opposition and firm counterattacks” of Hong Kong and mainland Chinese people. rad

The Israeli venture capital company DST Global is investing in Xiaohongshu, China’s fastest growing social media platform. The amount of the investment is not known. However, it is noteworthy because foreign investors have largely avoided China’s tech sector since Beijing’s crackdown.

Xiaohongshu was founded in 2013 and has 312 million monthly users. It is valued at 17 billion US dollars and has been profitable since last year. In 2023, revenue was 3.7 billion US dollars, and net profit was 500 million US dollars.

Xiaohongshu had arranged the sale of existing shares to existing and new investors in recent weeks. Hong Kong-based HongShan, formerly Sequoia China, and several Chinese private equity firms also took part in the round. jul

In addition to its security authorities, the leadership in Beijing also monitors China’s uniform public opinion using a sophisticated propaganda apparatus. This is ensured by so-called writing groups 写作组. Under the guidance of the highest Party committees, they write authoritative theoretical essays and, above all, demand unconditional obedience to helmsman Xi Jinping. Despite their normal names, few realize that the writers are not individual authors. Instead, they are anonymous employees of a collective. They use pseudonyms or homophones that only insiders understand. Bloggers, along with domestic and foreign China experts, have been tracing this sophisticated manipulation for years, which Beijing uses as a method of steering public discourse.

China’s history knows countless examples of writers, scholars and literati, imperial officials, warlords, even eunuchs who hid their true identity behind pseudonyms, stage and fake names 笔名. The Chinese language, with its myriad of characters and the freedom to choose first names at will, made it easy for Chinese people to choose pseudonyms. They were also often necessary to protect themselves from persecution, as the academic Kou Pengcheng 寇鹏程 discovered. He investigated the culture and influence of stage names and pseudonyms from ancient times to the People’s Republic right before the outbreak of Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

Changing their pseudonyms constantly was a must for writers. The most famous critical author of the modern era, Lu Xun (his real name was Zhou Shuren), used 168 pseudonyms throughout his life. The name of today’s Nobel Prize winner, Mo Yan (actually Mo Guanye), is also a pseudonym and has a profound meaning: I am one who does not talk (or has nothing to say). China’s new dictionary of pseudonyms and pen names 笔名 of famous authors from the time of the cultural renewal movement in 1919 to the present day 中国现代文学作者笔名大辞典 lists over 40,000 pen names used by more than 6,000 published authors.

Grotesquely, one particular species has not found its way into the reference work: Hundreds of authors who nowadays write political, economic and cultural essays and ideological treatises. The names under which they publish in the largest party media are pseudonyms, homophones or pen names. But the public must not know about this.

The best-known representative of this guild is the author Ren Zhongping 任仲平, who has been active for 30 years and whose commentaries and essays are reprinted everywhere in the People’s Daily. This year, Ren struck again on June 26 on the front page of the People’s Daily with a six-part essay. Despite the awkward title, “Let’s use the comprehensive deepening of our reforms as a fundamental driving force for Chinese-style modernization,” the essay was seen as a pre-announcement of Beijing’s new reform offensive, the starting signal for the Third Central Committee Plenum that will convene on July 15.

Whispers in Beijing immediately claimed that when Ren wrote, Communist Party leader Xi Jinping was behind it. Ren proclaimed that since taking office in 2012, Xi has always “personally planned, implemented and promoted everything” when it came to deepening reforms. This is also the case now. The name Ren Zhongping does not stand for a person, but is the pseudonym of the eponymous team of writers 写作组 of the People’s Daily – and a kind of disguised mouthpiece for the Politburo. It is derived from 人重评, the short form for人民日报重要评论, meaning “important commentary of the People’s Daily,” a homophone that is spelled differently but sounds the same.

Whenever major events are about to happen, Beijing has them announced by the Ren Zhongping group or other such teams working for the Politburo. They use pseudonyms to make outsiders believe that the authors are independent writers or journalists. In fact, their pseudonyms function as a kind of special “secret code,” as the renowned political scientists Wen-Hsuan Tsai and Peng Hsiang Kao from Taiwan’s Academia Sinica and the University of Science and Technology discovered. Ten years ago, they revealed the importance of these writing collectives for the Party’s monopoly on information. They said that Beijing was now increasingly “instrumentalizing” its special form of political propaganda.

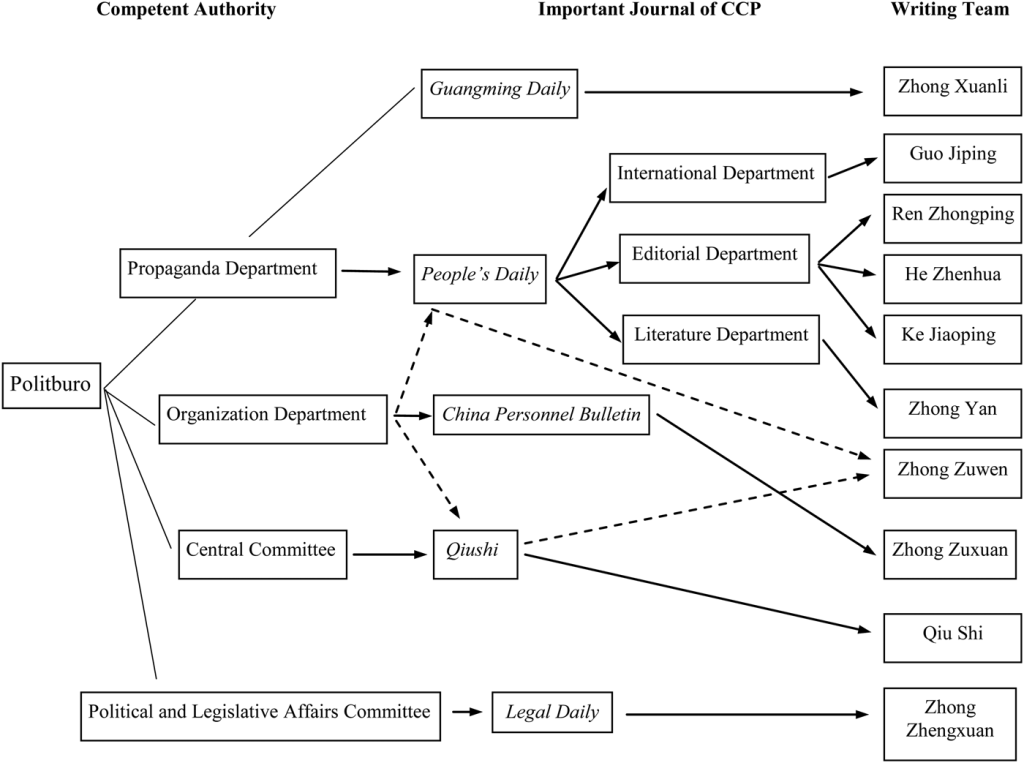

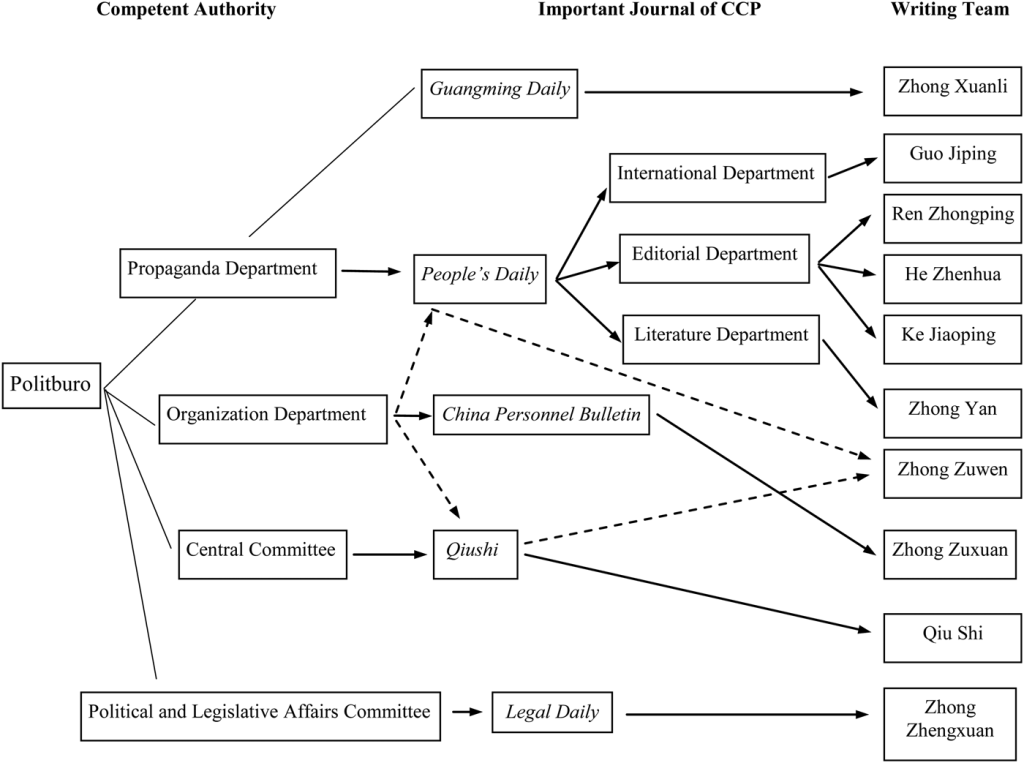

The detailed studies appeared in China Quarterly and Cambridge University Press. Using Ren Zhongping as an example, they explain how the system works. The political scientists drew up a chart of the connections for 10 of the 20 examples examined. Part of the “secret code” is interpreting the manipulated names and pseudonyms. They revealed which high party committee or Politburo represented which views.

In the meantime, Beijing has refined the system. Dozens of author teams have been cultivated under new pseudonyms, giving rise to a sophisticated Party media network. Beijing blogger Hu Ji revealed this, as well as the history of the secret battles under pseudonyms in the People’s Republic and during the Cultural Revolution. China expert and director of the China Media Project (CMP) David Bandurski also looked into this. He describes the propaganda system as a manipulation tool for the power struggles within the CCP leadership.

However, knowing which writing group belongs to whom under which pseudonym is not enough. You also have to read between the lines when Ren Zhongping praises Xi Jinping’s supposedly boundless enthusiasm for reform and for “a high-level socialist market economy.” He also quotes Xi’s warning: “…no matter how the reforms are carried out, (we absolutely must not allow) them to shake our fundamental basis of adhering to the all-round leadership of the Party, Marxism, the China-style socialist path and the democratic dictatorship of the people.” 改革无论怎么改,坚持党的全面领导、坚持马克思主义、坚持中国特色社会主义道路、坚持人民民主专政等根本的东西绝对不能动摇

In other words, China wants to be careful with its reforms, stepping firmly on the gas pedal with one foot and on the brakes with the other. Many scholars agree that Beijing’s policy of using pseudonyms is based on the ancient culture of ambiguity and allusions that continue to permeate the propaganda work of the CCP today. Moreover, its art of concealment prevents outsiders from recognizing or even noticing internal party disputes and disagreements. After all, the CCP must always maintain the façade of a united, harmonious party. Suggesting that Beijing should give more political transparency a try is a public taboo.

Pseudonyms, abbreviations and homonyms (谐音) under which comments and articles are published in CCP media and on websites:

Lu Tian has been a research assistant at the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation since June. The art historian, who trained in Beijing and Berlin, specializes in Buddhist art, East Asian art history and the cultural history of the Silk Road.

Choi Wai Hong Clifford was appointed new Managing Director of China Evergrande New Energy Vehicle on Wednesday. His predecessor Qin Liyong has to vacate the post.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Watching the big screen in collective suspense is something Europe is very familiar with at the moment. However, the residents of the small village of Huaying in Sichuan are watching a movie and not a European Championship match. With temperatures above 30 degrees, they have quickly converted the village square into an open-air cinema. There doesn’t seem to be any popcorn, but someone somewhere has certainly set up a stall with lamb skewers and cold beer.

It has been years of struggle: removing Huawei from Germany’s networks – yes or no? Security concerns and fears of espionage and sabotage spoke in favor of a clean-up. However, network operators protested loudly and refused to talk about a restructuring. Even the government was divided. It is now clear that the German government will ban components from Chinese manufacturers Huawei and ZTE from its 5G mobile networks – but this is essentially a sham solution.

In fact, the components have already been replaced in many parts of the core network. In other areas, the deadlines have been significantly extended. Yet nothing is being done for particularly critical infrastructures, such as government buildings in Berlin, Bundeswehr sites and NATO facilities. In their analysis, Michael Radunski and Felix Lee provide an overview of what has been decided and what criticism has been leveled at the decision.

China’s successful e-commerce platforms differ fundamentally from old-fashioned online shopping in Europe. Over here, people still go to Amazon, where they search for products in a nicely structured way: Categorized and filtered, relevant products appear on one page. Totally practical, completely emotionless. On the other hand, Chinese e-commerce apps such as Temu and Pinduoduo focus entirely on gamification. And Pinduoduo uses group buying to turn shopping into an experience with friends – if many people join in, the price drops.

The user experience also increasingly influences Western providers and their underlying business models. Amazon announced this month that it will increasingly use dealer networks from China, similar to Temu – without middlemen and the company’s own logistics centers. While Temu is in the spotlight for its competitive prices, there are growing security concerns about Pinduoduo. Fabian Peltsch provides an insight into the world of e-commerce giants.

The years-long dispute in Germany over how to deal with mobile communications components from China is coming to an end. The German government and network operators have reached a compromise on how to handle technology from Chinese companies. The result: not everything has to go. Nancy Faeser (SPD) explained this in Berlin on Thursday. “We have now reached a clear and strict agreement with the telecommunications companies,” said the Federal Minister of the Interior. Corresponding contracts will now be signed this week.

The fear is that companies such as Huawei and ZTE could use the technology for espionage or even commit sabotage on behalf of the Chinese government due to their close ties to the Communist Party. German mobile network operators, on the other hand, value Chinese technology for being inexpensive and efficient.

Specifically, the compromise agreed on the following points, all of which have been under discussion for some time:

Essentially, this compromise is a sham solution because it cleverly avoids having to make critical decisions.

Many mobile network operators had warned against excluding Chinese providers – especially Huawei. They were concerned that the quality of the mobile network could deteriorate. Germany’s digitalization is already behind that of many other developed and emerging countries. An analysis by telecommunications consultancy Strand Consult found that Huawei was responsible for almost 60 percent of Germany’s 5G network in 2022.

In response to the current compromise, Huawei once again dismissed all security concerns. The management of Huawei Germany stated that it has always been reliable and can boast an excellent security track record. “There is still no verifiable evidence or plausible scenarios that Huawei’s technology would pose a security risk in any form,” a Huawei spokesperson wrote in a statement.

And Huawei assures: “We will continue to work constructively and openly with our partners and customers to jointly achieve improvements and progress in the area of cybersecurity and to accelerate the development of mobile networks and digitalization in Germany.”

The reason for the slow decision-making process are the differing views in the German government:

Security authorities have been warning for some time about China’s attempts to penetrate critical infrastructures around the world. Security circles claim that China has already managed to gain a strong foothold in critical infrastructures in some countries. And 5G networks are of paramount importance.

Human rights groups have strongly condemned the decision. The spokesperson for the Tibet Initiative Germany speaks of a “poor compromise.” He said that instead of quickly removing Chinese components from the entire network, a minimal compromise had now been agreed. Only the software will be replaced in the antenna and access networks. It is doubtful whether this solution can be implemented at all, as Huawei and other Chinese manufacturers would have to willingly open up their hardware to new software.

But the decision also sends a fatal signal to Tibetans and other people persecuted by Beijing: “For these groups in particular, such a decision sows new doubts whether Germany has the will to provide a safe life in exile.” Collaboration: Felix Lee

Driven by the success of Temu and Shein, Amazon plans to source more goods directly from China. Without middlemen and without warehousing in Amazon’s own logistics centers, the aim is to have them reach the buyer within nine to eleven days. On average, these no-name products cost under 20 US dollars – conditions that Temu now offers in 50 countries and with which it is slowly stealing Amazon’s thunder.

According to Amazon, the number of Chinese sellers on the platform has already increased by more than 20 percent in 2023 compared to the previous year – partly because fees have been reduced for sellers who offer clothing for less than 20 US dollars. The modernization of the largest Western e-commerce provider is in full swing.

Like TikTok, Temu is also backed by a Chinese tech giant: Pinduoduo Holdings (PDD), a Nasdaq-listed company based in Shanghai. It was founded in 2015 by Colin Huang, a highly respected entrepreneur in China who previously worked as a software developer and product manager for companies including Google. A son of two factory workers from Hangzhou, he was recognized early on as a mathematical prodigy. He studied computer science at Zhejiang University and went to the USA in 2002, where he earned a master’s degree in computer science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. An impressed professor subsequently wrote him letters of recommendation for all leading US tech companies. Huang ended up working for Google, whose entry into the Chinese market he helped prepare.

After leaving Google, Huang founded several start-ups, including an online gaming company and an e-commerce website specializing in consumer electronics. The founding legend of Pinduoduo is that a middle ear infection put Huang out of action for more than a year.

During this time, the then 33-year-old realized that the two largest tech companies in China, Alibaba and Tencent, “didn’t really understand how the other company made money.” He then combined their and his areas of specialization, namely online games and e-commerce, to form Pinduoduo.

Huang’s company has long since caught up with the top dogs. In May, the company reported that it had tripled its net profit in the first three months of the fiscal year by 246 percent to around 3.6 billion euros compared to last year. The revenue of Alibaba and the other major e-commerce provider, JD.com, grew by less than 10 percent.

Pinduoduo generates most of its revenue, around 88 percent, from advertising. In 2023, two-thirds of revenue came from sellers who wanted to place their product offers more prominently on the website and app. A model that Huang learned from Google.

Pinduoduo has occupied niches in several respects. Firstly, the company has taken gamification to the next level. Countless addictive online games promise discounts. One market observer spoke of “dollar store meets Candy Crush.” The idea is for users to visit the app not so much with the intention of making a purchase, but to pass the time.

Secondly, Pinduoduo has set new benchmarks in China with the idea of group purchases. Users can receive discounts of up to 90 percent if they either initiate a group purchase themselves or join an existing group purchase.

Pinduoduo, which means “do more together” in Chinese, has turned the traditional retail model on its head – from supply-oriented to demand-oriented. Suppliers can reduce costs by responding directly to fluctuations in demand, for example. Shorter product development times allow small manufacturers and retailers to compete with larger suppliers.

In China, group purchasing helped skyrocket Pinduoduo’s user numbers through the word-of-mouth advertising inherent to the model. The app became a hit in WeChat groups in particular, which Tencent, soon to become one of Pinduoduo’s largest shareholders, supported with technology and funding. Pinduoduo also anticipated the changing purchasing behavior of the Chinese middle class. While companies like Alibaba focused more and more on premium products, Huang concentrated on less wealthy rural areas and “third-tier” cities with fewer than three million inhabitants from the outset. When the slowing economy forced people to save money, Pinduoduo was there at the right time with cheap offers.

Just like Amazon started out selling books, Huang initially focused on fresh fruit and vegetables straight from producers. China’s fresh fruit market grew rapidly in 2015, although less than three percent was sold online at the time. Unlike Temu, Pinduoduo still sells food on a large scale today. And this is not the only difference in the successful model. Instead of relying on word of mouth through group purchases, Temu relies primarily on targeted advertising campaigns abroad. In the United States, the company even ran TV ads during the Superbowl, the country’s biggest sporting event.

Like Temu in the West, Pinduoduo faced early criticism in China due to the poor quality of its products. Like TikTok’s parent company ByteDance, Pinduoduo is also increasingly in the spotlight overseas due to security concerns. Last year, the Pinduoduo app was blocked from the Google Play Store outside of China after cybersecurity experts discovered that it was infected with malware. Washington and Brussels discuss restrictions and bans on Temu.

Chen Lei, Co-Chief Executive and Chairman of PDD Holdings, explains that Temu’s global expansion is still at an early stage with many uncertainties. A collaboration with Amazon comes at just the right time. In addition to more Chinese retailers on Amazon, the US company has also launched its own Amazon store on Pinduoduo. This gives Amazon, whose market share in China is less than one percent, access to millions of Chinese consumers. And Pinduoduo may soon also be able to access Amazon’s global network of suppliers and logistics providers for Temu.

July 16, 2024; 4 p.m. Beijing time

German Chamber of Commerce, GCC Knowledge Hub: Explanation of Personal Income Tax Planning and Equity Structure for Foreign Enterprises More

July 16, 2024; 10 p.m. CEST (July 17, 4 a.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, book presentation and discussion: A New Cold War: Conversation with Sir Robin Niblett More

July 17, 2024; 10 p.m. CEST (July 18, 3 a.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, Webcast: The Importance of National Resilience: Implications for Taiwan More

July 18, 2024; 10 a.m. CEST (4 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Dezan Shira & Associates, Webinar: Hong Kong 2024: Unlocking Investment & Business Opportunities More

July 18, 2024; 10:30 a.m. CEST (4:30 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Sino-German Center at Frankfurt School, webinar with Joerg Wuttke and Prof. Klaus Muehlhahn: Results of The 3rd Plenum: Progress Ahead for The Economy? More

July 18, 2024; 3 p.m. CEST (9 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, Webcast: How does the Taiwan Public View the U.S. and China? More

July 19, 2024; 3 p.m. CEST (9 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, Webcast: A Fireside Discussion with U.S. Ambassador to China Nicholas Burns More

July 22, 2024; 3 p.m. CEST (9 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

Center for Strategic & International Studies, Webcast: China’s Third Plenum: A Plan for Renewed Reform? More

July 22, 2024; 11 a.m. CEST (4 p.m. Uhr Beijing time)

GIGA Hamburg, Seminar (Hybrid): Navigating Post-Pandemic Fieldwork in China: Challenges, Adaptations, and Insights More

The Chinese Foreign Ministry has protested on Thursday against the “illegal and inappropriate” actions of a Japanese ship that entered Chinese waters. Foreign Ministry spokesman Lin Jian announced at the regular press conference in Beijing that China will take action against all those who enter Chinese territory without permission. He added that Japan is expected not to allow such an incident to occur again.

The Japanese destroyer “Suzutsuki” entered Chinese waters off Zhejiang province on July 4, and China was planning to conduct naval exercises at the same time. The Kyodo news agency, citing diplomatic sources, reported that the Suzutsuki was monitoring Chinese missile exercises in the East China Sea north of Taiwan.

The authorities of Zhejiang had imposed a no-sailing zone in the area the day before so that the Chinese military could carry out the live-fire exercise. The Chinese government suspects a “deliberate provocation” behind the destroyer incident, which may have gathered security-related information. Despite direct warnings, the destroyer reportedly remained within twelve nautical miles of the coast of Zhejiang for around 20 minutes. The Japanese side spoke of a technical fault. The Ministry of Defense announced an investigation.

The incident further strains the already tense relations between China and Japan. The leadership in Tokyo is currently making great efforts to forge closer ties with other partners in the region. Just a few days ago, it signed a defense agreement with the Philippines. It will allow both countries to send troops to each other for joint military exercises. Cooperation with South Korea and the USA is also being intensified. All of this displeases the leadership in Beijing. rad

According to the human rights organization Human Rights Watch (HRW), aluminum products from Xinjiang should be included in the planned EU register of goods to assess the risk of forced labor.

The register is part of the EU regulation on products of forced labor. For this to have a concrete impact on state-imposed forced labor in China, the inclusion of Xinjiang and the aluminum sector in the database is crucial, HRW explained in a statement. The organization recommends a total of 17 sectors from clothing to toy production in the Xinjiang region that should be included in the EU register.

The EU would thus follow the US, which has added aluminum to the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) legislation, as Alejandro Mayorkas, US Secretary of Homeland Security, explained in an interview with the US think tank CSIS. Accordingly, the UFLPA also covers seafood and PVC.

The planned EU regulation is intended to prevent consumers from buying goods that have been produced using forced labor. The online database will publish specific geographical areas and sectors where there is a risk of forced labor, including by the state. The database should be available from 2026, with the regulation coming into force at the end of 2027. ari

The office of the Commissioner of the Chinese Foreign Ministry in Hong Kong sharply criticized the USA on Thursday. It called on the US government to end its “persecution fantasies.” The public statement further said that Washington should also stop interfering in Hong Kong’s affairs.

The reason for the outrage is that US President Joe Biden extended the “emergency status” over Hong Kong a few hours earlier. Biden cited “recent actions” by China in his justification: “The situation with respect to Hong Kong, including recent actions taken by the People’s Republic of China to fundamentally undermine Hong Kong’s autonomy, continues to pose an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States.”

This is the fourth extension of an order issued in 2020 that revokes Hong Kong’s status as a preferred trading partner. Former US President Donald Trump first declared the “national emergency.” It is a response to the National Security Law that Beijing imposed on Hong Kong after months of anti-government protests since 2019.

The Chinese response added that the US should “immediately stop its self-humiliating political act” or face the “collective opposition and firm counterattacks” of Hong Kong and mainland Chinese people. rad

The Israeli venture capital company DST Global is investing in Xiaohongshu, China’s fastest growing social media platform. The amount of the investment is not known. However, it is noteworthy because foreign investors have largely avoided China’s tech sector since Beijing’s crackdown.

Xiaohongshu was founded in 2013 and has 312 million monthly users. It is valued at 17 billion US dollars and has been profitable since last year. In 2023, revenue was 3.7 billion US dollars, and net profit was 500 million US dollars.

Xiaohongshu had arranged the sale of existing shares to existing and new investors in recent weeks. Hong Kong-based HongShan, formerly Sequoia China, and several Chinese private equity firms also took part in the round. jul

In addition to its security authorities, the leadership in Beijing also monitors China’s uniform public opinion using a sophisticated propaganda apparatus. This is ensured by so-called writing groups 写作组. Under the guidance of the highest Party committees, they write authoritative theoretical essays and, above all, demand unconditional obedience to helmsman Xi Jinping. Despite their normal names, few realize that the writers are not individual authors. Instead, they are anonymous employees of a collective. They use pseudonyms or homophones that only insiders understand. Bloggers, along with domestic and foreign China experts, have been tracing this sophisticated manipulation for years, which Beijing uses as a method of steering public discourse.

China’s history knows countless examples of writers, scholars and literati, imperial officials, warlords, even eunuchs who hid their true identity behind pseudonyms, stage and fake names 笔名. The Chinese language, with its myriad of characters and the freedom to choose first names at will, made it easy for Chinese people to choose pseudonyms. They were also often necessary to protect themselves from persecution, as the academic Kou Pengcheng 寇鹏程 discovered. He investigated the culture and influence of stage names and pseudonyms from ancient times to the People’s Republic right before the outbreak of Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

Changing their pseudonyms constantly was a must for writers. The most famous critical author of the modern era, Lu Xun (his real name was Zhou Shuren), used 168 pseudonyms throughout his life. The name of today’s Nobel Prize winner, Mo Yan (actually Mo Guanye), is also a pseudonym and has a profound meaning: I am one who does not talk (or has nothing to say). China’s new dictionary of pseudonyms and pen names 笔名 of famous authors from the time of the cultural renewal movement in 1919 to the present day 中国现代文学作者笔名大辞典 lists over 40,000 pen names used by more than 6,000 published authors.

Grotesquely, one particular species has not found its way into the reference work: Hundreds of authors who nowadays write political, economic and cultural essays and ideological treatises. The names under which they publish in the largest party media are pseudonyms, homophones or pen names. But the public must not know about this.

The best-known representative of this guild is the author Ren Zhongping 任仲平, who has been active for 30 years and whose commentaries and essays are reprinted everywhere in the People’s Daily. This year, Ren struck again on June 26 on the front page of the People’s Daily with a six-part essay. Despite the awkward title, “Let’s use the comprehensive deepening of our reforms as a fundamental driving force for Chinese-style modernization,” the essay was seen as a pre-announcement of Beijing’s new reform offensive, the starting signal for the Third Central Committee Plenum that will convene on July 15.

Whispers in Beijing immediately claimed that when Ren wrote, Communist Party leader Xi Jinping was behind it. Ren proclaimed that since taking office in 2012, Xi has always “personally planned, implemented and promoted everything” when it came to deepening reforms. This is also the case now. The name Ren Zhongping does not stand for a person, but is the pseudonym of the eponymous team of writers 写作组 of the People’s Daily – and a kind of disguised mouthpiece for the Politburo. It is derived from 人重评, the short form for人民日报重要评论, meaning “important commentary of the People’s Daily,” a homophone that is spelled differently but sounds the same.

Whenever major events are about to happen, Beijing has them announced by the Ren Zhongping group or other such teams working for the Politburo. They use pseudonyms to make outsiders believe that the authors are independent writers or journalists. In fact, their pseudonyms function as a kind of special “secret code,” as the renowned political scientists Wen-Hsuan Tsai and Peng Hsiang Kao from Taiwan’s Academia Sinica and the University of Science and Technology discovered. Ten years ago, they revealed the importance of these writing collectives for the Party’s monopoly on information. They said that Beijing was now increasingly “instrumentalizing” its special form of political propaganda.

The detailed studies appeared in China Quarterly and Cambridge University Press. Using Ren Zhongping as an example, they explain how the system works. The political scientists drew up a chart of the connections for 10 of the 20 examples examined. Part of the “secret code” is interpreting the manipulated names and pseudonyms. They revealed which high party committee or Politburo represented which views.

In the meantime, Beijing has refined the system. Dozens of author teams have been cultivated under new pseudonyms, giving rise to a sophisticated Party media network. Beijing blogger Hu Ji revealed this, as well as the history of the secret battles under pseudonyms in the People’s Republic and during the Cultural Revolution. China expert and director of the China Media Project (CMP) David Bandurski also looked into this. He describes the propaganda system as a manipulation tool for the power struggles within the CCP leadership.

However, knowing which writing group belongs to whom under which pseudonym is not enough. You also have to read between the lines when Ren Zhongping praises Xi Jinping’s supposedly boundless enthusiasm for reform and for “a high-level socialist market economy.” He also quotes Xi’s warning: “…no matter how the reforms are carried out, (we absolutely must not allow) them to shake our fundamental basis of adhering to the all-round leadership of the Party, Marxism, the China-style socialist path and the democratic dictatorship of the people.” 改革无论怎么改,坚持党的全面领导、坚持马克思主义、坚持中国特色社会主义道路、坚持人民民主专政等根本的东西绝对不能动摇

In other words, China wants to be careful with its reforms, stepping firmly on the gas pedal with one foot and on the brakes with the other. Many scholars agree that Beijing’s policy of using pseudonyms is based on the ancient culture of ambiguity and allusions that continue to permeate the propaganda work of the CCP today. Moreover, its art of concealment prevents outsiders from recognizing or even noticing internal party disputes and disagreements. After all, the CCP must always maintain the façade of a united, harmonious party. Suggesting that Beijing should give more political transparency a try is a public taboo.

Pseudonyms, abbreviations and homonyms (谐音) under which comments and articles are published in CCP media and on websites:

Lu Tian has been a research assistant at the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation since June. The art historian, who trained in Beijing and Berlin, specializes in Buddhist art, East Asian art history and the cultural history of the Silk Road.

Choi Wai Hong Clifford was appointed new Managing Director of China Evergrande New Energy Vehicle on Wednesday. His predecessor Qin Liyong has to vacate the post.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Watching the big screen in collective suspense is something Europe is very familiar with at the moment. However, the residents of the small village of Huaying in Sichuan are watching a movie and not a European Championship match. With temperatures above 30 degrees, they have quickly converted the village square into an open-air cinema. There doesn’t seem to be any popcorn, but someone somewhere has certainly set up a stall with lamb skewers and cold beer.