With its 16+1 format, China wanted to weaken the EU’s position in Eastern and Central Europe in the long term. But ten years after the foundation of the economic initiative, disillusionment is now spreading. The economic benefits are limited. Financial aid has turned out to be smaller than expected. Negotiations have been tough, and political differences, such as sanctioned relations with Taiwan and China’s stance on the Ukraine war, have led to a serious loss of trust. Most recently, Latvia and Estonia turned their backs on the initiative. Although the Czech Republic is likely to follow soon, a large wave of withdrawals is not likely, analyzes Amelie Richter. Many of the countries maintain relatively close ties with China and hope to attract further investment – and the EU is still not present enough as an alternative.

China’s movie industry also shows a tendency to decouple. As our team in Beijing reports, fewer and fewer Western blockbusters are making their way to China. This is partly due to the authorities’ non-transparent pre-selection process – only 34 foreign movies are allowed to be shown each year – and partly due to changing tastes. The Chinese have begun to show greater interest in Chinese productions with Chinese themes, preferably patriotic and bombastic, such as the box-office hit Battle at Lake Changjin, the first part of which alone grossed $900 million.

The proposal sounded promising: A major power wants to channel money into Central and Eastern European states, develop infrastructure, revive old factories, and invest in people and local projects that are unable to attract Western investors. The 16+1 format appeared on the scene and a race to become “China’s gateway to Europe” began. For some participants, however, the finish line never came in sight, and economic hopes remained unfulfilled. There are no fireworks to mark the tenth anniversary of its founding. Instead, the cooperation format continues to shrink with the withdrawal of Latvia and Estonia.

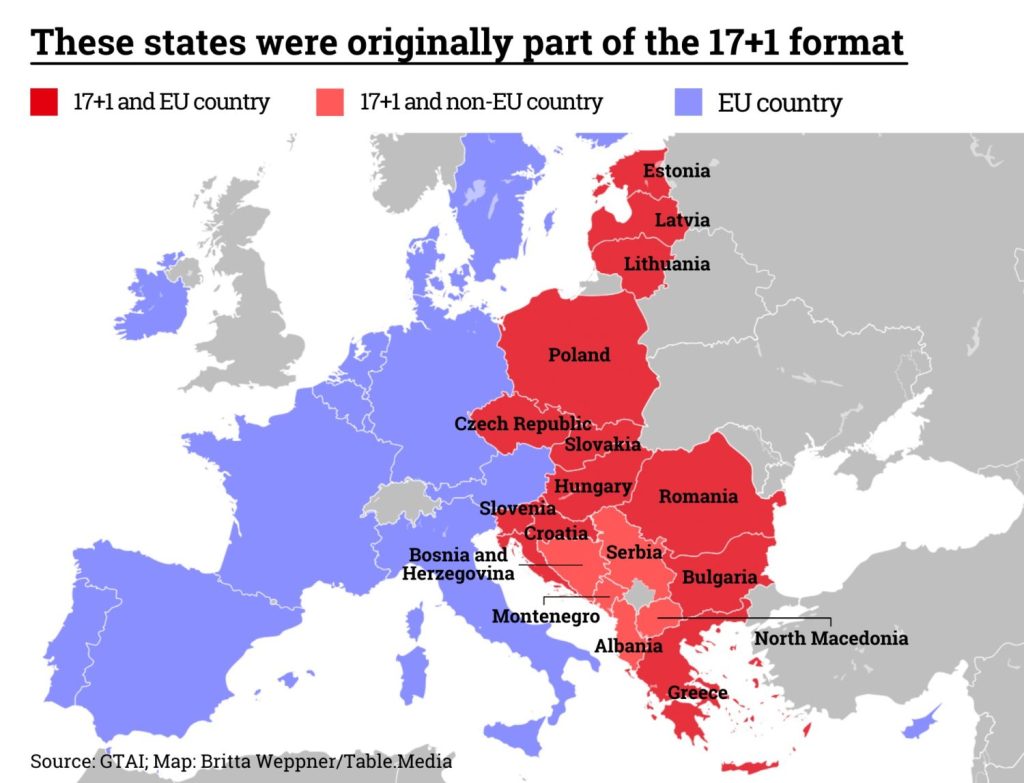

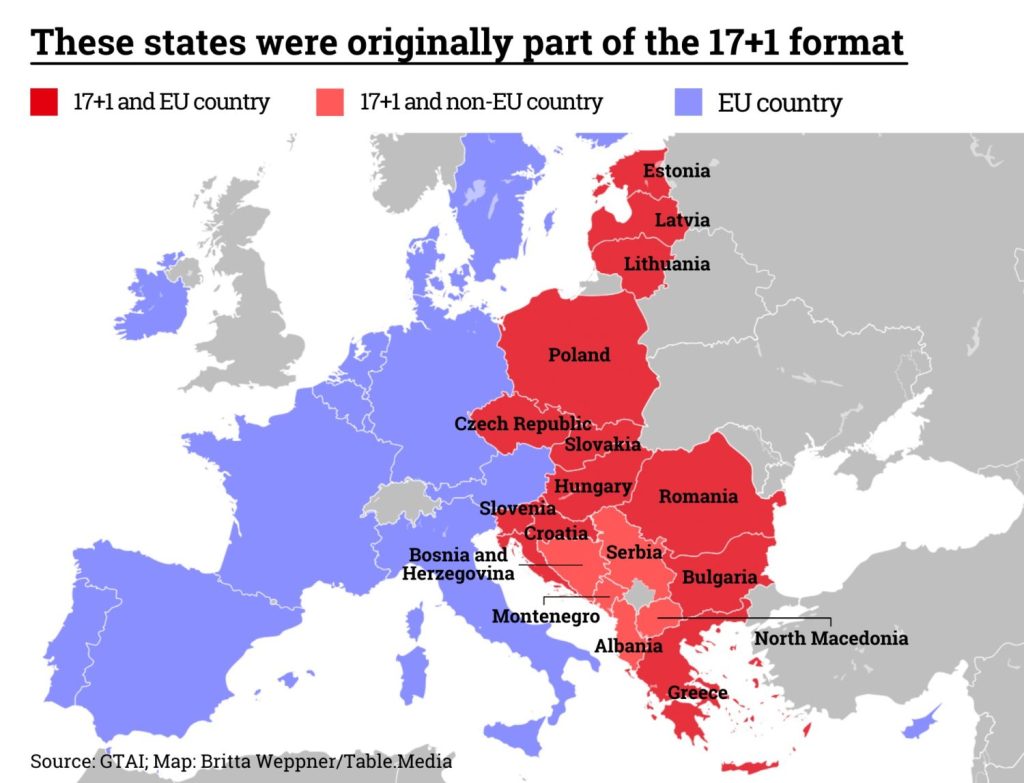

In 2012, the “Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries”, or China-CEEC, was formed. It included 16 countries in Central and Eastern Europe and the People’s Republic. After Greece joined, it was given the unofficial name 17+1. In 2021, Lithuania took the first step, left the cooperation format, and changed its name back to 16+1.

Since last week, the numbers have to be re-counted again. With the coordinated withdrawal of the Baltic EU states Estonia and Latvia, there are now only 14+1 left (China.Table reported). The remaining 14 consist of the 9 EU member states Bulgaria, Greece, Croatia, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Czech Republic and Hungary. In addition, there are the Five Western Balkan states of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro and North Macedonia.

The withdrawal is unsurprising, says Liisi Karindi, an analyst at the think tank China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe (CHOICE). In her home country of Estonia, she says, China has long ceased to be perceived as an economic opportunity and has become more of a national security issue. “Politically and economically, China has never been that important to us,” Karindi tells China.Table.

Estonia, just like Lithuania and Latvia, is more at the bottom of the list of recipients of Chinese investments. And according to the United Nations Comtrade database on international trade, Estonian exports to China amounted to just $232 million in 2021.

Much more important and present in Estonian public perception is another major power, Karindi said. “For us in the Baltics, the question is always, what is Russia doing?” Because of the proximity, “sides had to be chosen pretty quickly”. The choice fell on the United States and NATO. The Russian attack on Ukraine and China’s reaction was also decisive for Estonia’s decision to leave the cooperation format. The possible damage to relations with China due to the withdrawal is “collateral damage,” says Karindi. The point was to take a clear stand against China’s role in the Ukraine war and against human rights violations. “Walk the talk,” as Karindi puts it. It was important to follow words with actions.

Latvia issued a similar announcement to Estonia last Thursday and announced its withdrawal. Just the day before, there had been talks about a possible expansion of cooperation in the transport sector.

What was surprising is the lack of a reaction from Beijing. Neither at the weekend nor at the beginning of the new week was there any official comment on the Baltic states’ withdrawal. A year ago, Lithuania caused a much bigger stir. Because after the withdrawal from the format, Vilnius immediately also initiated a rapprochement with Taiwan. The announcement of plans to set up a “Taiwan office” in the Lithuanian capital was the starting point of an unprecedented downfall of diplomatic and economic relations. Analyst Karindi does not believe that Estonia could now face a similar fate. There were currently no concrete plans on the part of the government to set up a “Taiwan office” in the country. However, the influential chairman of the Estonian parliament’s foreign policy committee, Marko Mihkelson, is indeed calling for such an office.

Is the Baltic exit now the beginning of a major wave of exits from CEEC-China? Probably not. The composition of its members is too heterogeneous for that – too many different interests in different states. Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia do not serve as a model for states such as Serbia or Montenegro when it comes to relations with China. For the Western Balkan states, Chinese offers are still financially interesting and will remain so because the EU’s presence is too small.

The end of 14+1 will only be ushered in when one of the leading heavyweights such as Hungary, Poland, Romania or the Czech Republic leaves the fold. Hungary, however, will now be the site of a new battery factory by CATL. The size of the investment: €7.34 billion (China.Table reported). The fact that this was announced just the day after Latvia and Estonia announced their withdrawal was read by some observers as an indirect reaction to the Baltic exit.

Poland and Romania are growing increasingly skeptical about Chinese investment. In Romania, all Chinese projects have been frozen. In 2020, the Romanians broke off talks with the Chinese about the Cernavoda nuclear power plant after seven years of negotiations. In Poland, the biggest project is the freight railroad running along the Land Silk Road from China. Trains continued to run there despite problems in 2021 on the Polish-Belarusian border and now during the Russian war in Ukraine. The biggest economic problem between Poland and the People’s Republic is the trade deficit. However, skepticism toward China does not seem to be pushing the governments in Warsaw and Bucharest to leave the cooperation format at this time.

The most likely candidate for withdrawal is the Czech Republic. Here, the question is not if, but when the step will be taken, as Ivana Karásková, China Research Fellow at the Association for International Affairs (AMO) in Prague, writes. Since the new Prime Minister Petr Fiala took office, the Czech Republic has been making more critical statements about China. Czech Foreign Minister Jan Lipavský is in favor of closer ties with Taiwan. In addition, the Foreign Ministry echoed the assessment that the format has brought the Czech Republic virtually no benefits over a decade of membership.

The Foreign Affairs Committee of the Czech Chamber of Deputies has already specifically called for withdrawal in a resolution. However, the Czech Republic still has to get rid of one “hurdle”: President Miloš Zeman. Zeman is Beijing’s champion. He personally attended the CEEC-China summit last year online. Since Zeman will not be allowed to run for re-election in January, the Czech Republic is expected to leave 14+1 next year.

Fans of superhero movies in China are on a two-year dry spell. Although China’s movie theaters reopened their doors fairly quickly during the Covid pandemic, Hollywood blockbusters were absent. Global box office hits like Black Widow, Shang Chi and Spider-Man: No Way Home have not made it to the Chinese market.

The gateway for superhero movies is clogged. The new Marvel movie Thor – Love and Thunder joins a long list of unreleased Marvel movies, although Avengers: Endgame grossed more than $629 million in China alone in 2019, a major contributor to the movie’s $2.7 billion worldwide. The release of The Batman in March and this week’s Minions: The Rise Of Gru put movie fans and industry analysts back on a more positive note. However, the trend is moving in a different, clear direction.

There is no official reason why US films are not granted licenses in China. This often leads to wild speculation. In the case of Thor – Love and Thunder, it is speculated that a kiss between two same-sex characters could be the reason. For Spider-Man: No Way Home, the Statue of Liberty was allegedly too often on screen. But this fate also befell non-Marvel movies. For Top Gun: Maverick, the cause was allegedly a Japanese and a Taiwanese flag on Tom Cruise’s flight jacket. However, such speculation cannot be confirmed.

What is new is that movies are more often completely excluded. In the past, censors often cut out the corresponding scenes or ordered content changed using computer effects. Naturally, the non-appearance of the movies does not benefit either side financially.

If previous major Marvel releases are anything to go by, a movie like Spider-Man: No Way Home could have expected revenues in the triple-digit millions. 75 percent of that would have fallen to Chinese contractors. This clearly shows that both sides are losing revenue. And the Chinese cinema market could actually have used the money just as much as the US companies. Cinema markets across the globe have suffered under the Covid crisis. Worldwide, revenues are between 30 and 40 percent below the average figures of the last three years. The difference between the Chinese market and the global market: In China, the numbers are currently declining, while elsewhere they are slowly recovering.

According to a study by Comscore Movies, North America has once again overtaken China as the largest movie market this year. However, the difference is only $3 million. China also seems to shift towards decoupling and strong domestic movie productions. The biggest Chinese box office hits of the past two years were Battle of Lake Changjin (about $900 million) and Battle of Changjin II (about $630 million), both of them patriotic action movies. It is a trend that has been going on for years. The share of US productions in the total revenue of the Chinese market is dropping. While it was 38 percent in 2016, US movies accounted for only 12.3 percent in 2021.

So there is a shift to domestic productions. “There is a huge demand for Chinese content among Chinese viewers,” says an industry insider. “These aren’t necessarily people from Beijing or Shanghai, but Chinese content is extremely popular in smaller cities.” Strained US-China relations further exacerbate this trend. Movies like “Battle of Lake Changjin,” in which the US is portrayed as the enemy, are accordingly booming. The fact that they are also technically well-made means that viewers in modern cities can also appreciate them.

To make matters worse, movies such as Dune or, more recently, The Batman have only attracted few viewers to cinemas. The latter completely bombed on the Chinese market – it made less than $30 million. ” This has dampened interest among movie distributors. They can often make more money with Chinese releases than they would with the extra effort that comes with a US movie.”

The Chinese government also has an interest in protecting Chinese movie companies. Only a little more than 34 foreign blockbusters are allowed to be released on the Chinese market under revenue sharing. In 2021, it was just 20. And sharing part of their revenue is significantly less lucrative for US studios in China than in other markets. After all, compared to the 40 to 50 percent of revenue they earn in other movie markets, they only take about 25 percent in China. And the censorship sword of Damocles hangs over every release.

A situation that is also causing resentment among US studio executives. This is because business with the Chinese side is becoming more and more unpredictable. “We sometimes put a guess in the China column, but more often it is blank or we run two models – with and without China,” a veteran financier told Hollywood Reporter magazine. US studios are no longer dependent on the Chinese market, anyway. “The China market remains at once too great an opportunity to disregard and too unpredictable to rely on,” concludes Rance Pow, President of Artisan Gateway, Asia’s leading film and cinema industry consulting firm.

For US studios, the Chinese market is more of an extra income. But for Chinese companies, it is different. They depend on their market. After all, even the most successful Chinese films generate almost no box-office revenue outside China. Joern Petring/Gregor Koppenburg

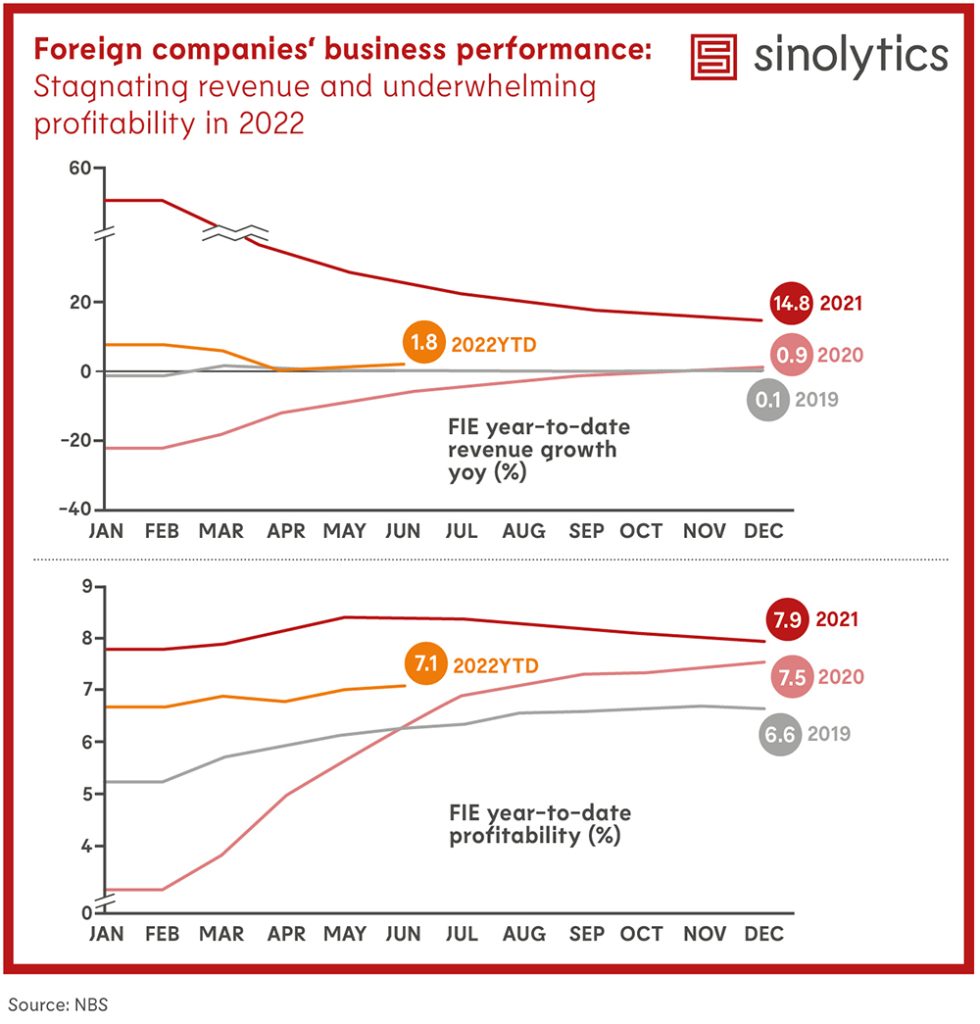

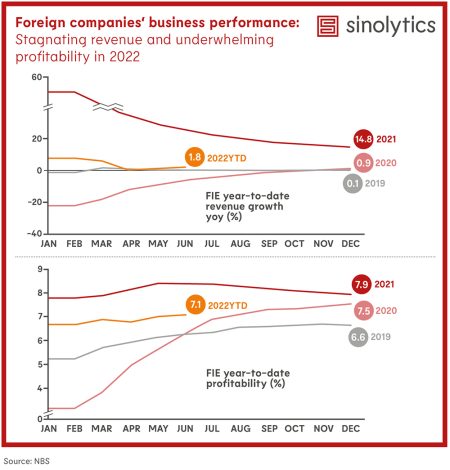

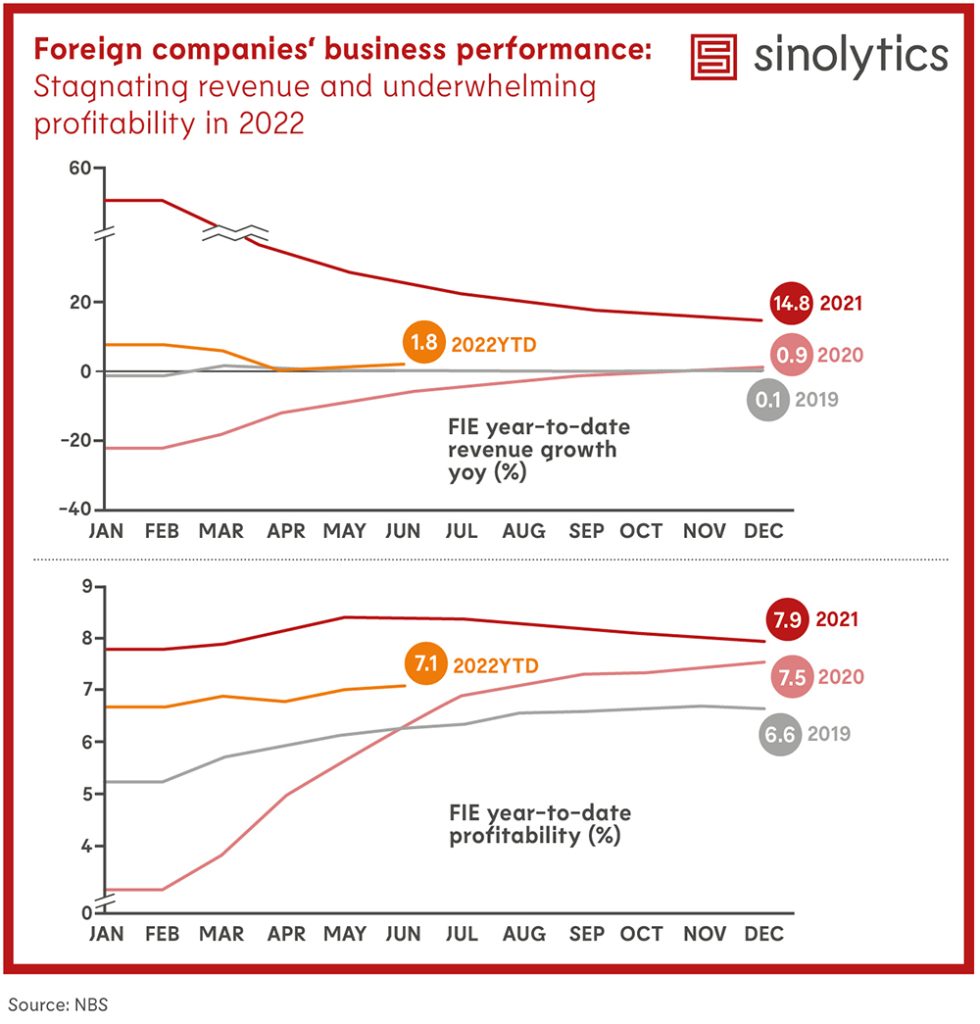

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

This week, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) published for the first time a list of details and functionalities of algorithms used in the apps of large Internet corporations such as Tencent, Alibaba, Meituan and ByteDance. In doing so, China’s Internet regulator aims to allow users deeper insight and self-determination and “promote healthy development of Internet information services,” according to officials. Many online platforms base their business model on recommendation algorithms that bind users to their services based on individual data.

Beijing has accused Internet platforms of using algorithms to invade users’ privacy and manipulate their decisions. Consequently, the government passed a law in the spring that allows users to view recommendations made by algorithms within apps and online platforms and even disable them if desired. The law, titled “Internet Information Service Algorithmic Recommendation Management Provisions,” is the first of its kind. No other country allows users to extensively disable algorithms in their apps. (China.Table reported).

The list published by the CAC lists 30 algorithms and provides brief explanations. According to the list, Alibaba’s Taobao e-commerce app, for example, uses a recommendation algorithm that evaluates each user’s visit and search history to recommend products and services. Delivery service Meituan provides details about its algorithm, which is used to estimate delivery times and match drivers’ assignments. The list will be continuously expanded, according to the cyberspace administration. rtr/fpe

After more than a year of boycott, H&M is once again allowed to sell products on the Chinese e-commerce platform Tmall. The Swedish textile retailer, which has a good 14 million subscribers on Tmall, had been removed from Tmall and other online retail sites in March 2021 due to critical statements about the origin of Xinjiang cotton (China.Table reported). Tmall is China’s largest B2C shopping platform with more than 500 million registered users.

In 2020, the fashion group stated that it was “deeply concerned by … accusations of forced labor” in cotton production in China and would no longer source products from Xinjiang. The shitstorm on China’s social media, which flared up just a year later, highlights the risks Western companies face in an increasingly nationalistic China. In the wake of the escalation, H&M was also forced to close around 60 of its stores in China – about 12 percent of its total retail network in China.

Behind closed doors, H&M had been in talks to return, insiders tell Bloomberg. With a share of only 3 percent in the global business, China is not vital to the retailer’s survival. However, the People’s Republic is the largest production site for H&M. fpe

Due to high temperatures and lack of rainfall, the water level on China’s longest river, the Yangtze, has fallen to its lowest ever recorded level. A level of 17.54 meters was measured in Wuhan – six meters below the average of recent years and the lowest level since 1865, as reported by the South China Morning Post. A good third of the Chinese population lives along the Yangtze.

The two largest freshwater lakes in the People’s Republic are recording the lowest levels since 1951. The Poyang and the Dongting are connected to the Yangtze. Smaller rivers have also begun to dry up. Southern China has been experiencing peak temperatures since July. The National Meteorological Center has now issued the highest alert for the entire region for the first time, according to the SCMP. Accordingly, 2022 could become the hottest year since 1961.

While low water levels in Germany have so far mainly caused trouble for barge operators, they pose a threat to power generation in China. In the province of Sichuan, the flow of water into hydroelectric dams has dropped by 50 percent from the historical average, Bloomberg reports. Authorities called on companies to conserve electricity and halt production, according to Reuters. Toyota responded by stopping assembly lines at its plant in the province until Saturday. Volkswagen reported that the local plant only experienced minor shipping delays. Foxconn’s Chengdu plant will also remain closed until Saturday. Producers of lithium, polysilicon, fertilizers and other goods have curtailed production.

Some villages around the Chongqing metropolis experienced a drinking water shortage. The fire department provided residents with fresh water for irrigation and consumption. nib

Shanghai biotech Stemirna Therapeutics has begun a Phase 1 trial for its COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The company has been working on the drug since spring 2021 (China.Table reported). Three other Chinese mRNA vaccines are already undergoing clinical trials. The hope now rests on the four vaccine candidates to break the country out of the lockdown trap. A phase 1 trial will initially test a new agent on a small number of people to determine its effects.

Meanwhile, the number of new Sars-CoV-2 infections is again on the rise in several Chinese regions. This raises new lockdown fears. The trend was most striking on the resort island of Hainan, where authorities identified 1,211 new cases. The total number of new infections was 2,368, with Hainan followed by Tibet and Xinjiang in the statistics. Three new cases were found in Shanghai and four in Beijing. fin

China’s authorities continue to admit critical minds to psychiatric hospitals on a large scale without any medical reasons. The Spanish human rights organization Safeguard Defenders has documented 99 cases of hospitalizations following expressions of opinion. Among them are many signatories of petitions who only used official channels to call for improvement of conditions and were classified as dangerous troublemakers for doing so.

The Ministry of Public Security (PSB) operates its own institutions for this purpose: “compulsory treatment institutions” 强制医疗所, commonly known as Ankang 安康 after their old name. They specialize in “criminal, mentally disturbed subjects”. Those committed are faced with sedation using severe medication, electric shocks, and isolation. Some victims spend more than ten years in such facilities. fin

As a student, Christine Althauser always earned skeptical looks whenever her classes and interests were discussed. Political science – not particularly exciting. But Sinology and Slavic Studies as minors? One year of studies in Taiwan and one in Moscow? That sometimes won her horrified looks.

But Althauser was not discouraged from her fascination with Asia and Eastern Europe. Rightly so, as she reflects today. The expertise she acquired in language, culture, politics and society made her numerous foreign assignments possible in the first place.

In her 34-year career, the German Foreign Office had repeatedly sent Christine Althauser to countries with which she already had contact during her studies: twice to Russia, twice to China. Directly after her attaché training in 1987, she came to the German Embassy in Beijing. This was followed by posts at several European embassies, the Permanent Representation to the European Union, the planning staff of the Federal Ministry of Defense and as head of the crisis prevention unit at the Federal Foreign Office. In between, she also earned her doctorate at the University of Heidelberg and lectured at the University of Freiburg. At the end of the 1990s, she was deployed in Russia.

In 2017 came the posting to Shanghai as Consul General. Althauser already knew the metropolis from previous visits as lively and international. However, everything changed with the first lockdown in Wuhan in 2020. Thus, on the final stop of her active career, she witnessed the city’s journey into Covid state of emergency. Although the situation stabilized over the year, she experienced the harbingers of the particularly strict curfews in 2022. But by then she had already left the post.

One can never be fully prepared for profound turning points such as a pandemic, but Althauser already experienced a similar moment in her past, at the very beginning of her career, in Beijing. At that time, she worked in the cultural department, interacted with writers and was in the midst of the flourishing life of the artistic scene – until dialogue came to a brutal end in 1989. It was then that she realized how defining, fast and radical a supposedly stable situation can change.

Althauser is now officially retired, a title she’s not particularly comfortable with. “They should think about renaming it,” she says. She believes she still has a lot to offer from the expertise she has acquired over all these years. Accordingly, she is still tirelessly on the road; last year alone, she helped monitor elections in Georgia and Serbia and led a diplomats’ course in Berlin. New missions are already lined up.

For Althauser, “the exchange with normal people from everyday life, away from professional involvement,” was always of great importance. One of her favorite memories of Shanghai were the many trips by bicycle and on foot, during which she discovered enchanted nooks and crannies full of hidden stories.

Althauser is concerned that the opportunities for such experiences are increasingly disappearing: “The fewer exchanges there are, the more stereotypes will gain the upper hand.” Christine Althauser has set herself the goal of helping to counteract this trend, especially under difficult conditions. Julius Schwarzwälder

Jing Du took up the position of Digital Marketing Manager at Melchers China in August. The marketing expert wants to break new ground in digital communication at the Bremen-based service provider for market expansion and trade. Jing previously worked for the German Chamber of Commerce Abroad and the German Academic Exchange Service in China, among others.

Uwe Schroeter has moved within the SMS Group from Moscow to Beijing, where he has been responsible for the China region as Chief Operating Officer since July. The SMS Group is an internationally operating company in the field of metallurgical and rolling mill technology with headquarters in Düsseldorf. Schroeter already worked for the company as Vice President Service Division in China between 2010 and 2019.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

The Yuan Wang 5 tracking ship in the port of Hambantota, Sri Lanka. Ships of this design can track missiles such as rockets with their large parabolic antennas. They perform civilian tasks such as monitoring satellite launches; they can also maintain contact with man-made orbital devices outside Chinese territory. However, these vessels can also provide support to the military. The presence of the Chinese ship in the port, which was financed with Silk Road funds, is therefore likely to be seen as another ominous sign of Chinese influence.

With its 16+1 format, China wanted to weaken the EU’s position in Eastern and Central Europe in the long term. But ten years after the foundation of the economic initiative, disillusionment is now spreading. The economic benefits are limited. Financial aid has turned out to be smaller than expected. Negotiations have been tough, and political differences, such as sanctioned relations with Taiwan and China’s stance on the Ukraine war, have led to a serious loss of trust. Most recently, Latvia and Estonia turned their backs on the initiative. Although the Czech Republic is likely to follow soon, a large wave of withdrawals is not likely, analyzes Amelie Richter. Many of the countries maintain relatively close ties with China and hope to attract further investment – and the EU is still not present enough as an alternative.

China’s movie industry also shows a tendency to decouple. As our team in Beijing reports, fewer and fewer Western blockbusters are making their way to China. This is partly due to the authorities’ non-transparent pre-selection process – only 34 foreign movies are allowed to be shown each year – and partly due to changing tastes. The Chinese have begun to show greater interest in Chinese productions with Chinese themes, preferably patriotic and bombastic, such as the box-office hit Battle at Lake Changjin, the first part of which alone grossed $900 million.

The proposal sounded promising: A major power wants to channel money into Central and Eastern European states, develop infrastructure, revive old factories, and invest in people and local projects that are unable to attract Western investors. The 16+1 format appeared on the scene and a race to become “China’s gateway to Europe” began. For some participants, however, the finish line never came in sight, and economic hopes remained unfulfilled. There are no fireworks to mark the tenth anniversary of its founding. Instead, the cooperation format continues to shrink with the withdrawal of Latvia and Estonia.

In 2012, the “Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries”, or China-CEEC, was formed. It included 16 countries in Central and Eastern Europe and the People’s Republic. After Greece joined, it was given the unofficial name 17+1. In 2021, Lithuania took the first step, left the cooperation format, and changed its name back to 16+1.

Since last week, the numbers have to be re-counted again. With the coordinated withdrawal of the Baltic EU states Estonia and Latvia, there are now only 14+1 left (China.Table reported). The remaining 14 consist of the 9 EU member states Bulgaria, Greece, Croatia, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Czech Republic and Hungary. In addition, there are the Five Western Balkan states of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro and North Macedonia.

The withdrawal is unsurprising, says Liisi Karindi, an analyst at the think tank China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe (CHOICE). In her home country of Estonia, she says, China has long ceased to be perceived as an economic opportunity and has become more of a national security issue. “Politically and economically, China has never been that important to us,” Karindi tells China.Table.

Estonia, just like Lithuania and Latvia, is more at the bottom of the list of recipients of Chinese investments. And according to the United Nations Comtrade database on international trade, Estonian exports to China amounted to just $232 million in 2021.

Much more important and present in Estonian public perception is another major power, Karindi said. “For us in the Baltics, the question is always, what is Russia doing?” Because of the proximity, “sides had to be chosen pretty quickly”. The choice fell on the United States and NATO. The Russian attack on Ukraine and China’s reaction was also decisive for Estonia’s decision to leave the cooperation format. The possible damage to relations with China due to the withdrawal is “collateral damage,” says Karindi. The point was to take a clear stand against China’s role in the Ukraine war and against human rights violations. “Walk the talk,” as Karindi puts it. It was important to follow words with actions.

Latvia issued a similar announcement to Estonia last Thursday and announced its withdrawal. Just the day before, there had been talks about a possible expansion of cooperation in the transport sector.

What was surprising is the lack of a reaction from Beijing. Neither at the weekend nor at the beginning of the new week was there any official comment on the Baltic states’ withdrawal. A year ago, Lithuania caused a much bigger stir. Because after the withdrawal from the format, Vilnius immediately also initiated a rapprochement with Taiwan. The announcement of plans to set up a “Taiwan office” in the Lithuanian capital was the starting point of an unprecedented downfall of diplomatic and economic relations. Analyst Karindi does not believe that Estonia could now face a similar fate. There were currently no concrete plans on the part of the government to set up a “Taiwan office” in the country. However, the influential chairman of the Estonian parliament’s foreign policy committee, Marko Mihkelson, is indeed calling for such an office.

Is the Baltic exit now the beginning of a major wave of exits from CEEC-China? Probably not. The composition of its members is too heterogeneous for that – too many different interests in different states. Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia do not serve as a model for states such as Serbia or Montenegro when it comes to relations with China. For the Western Balkan states, Chinese offers are still financially interesting and will remain so because the EU’s presence is too small.

The end of 14+1 will only be ushered in when one of the leading heavyweights such as Hungary, Poland, Romania or the Czech Republic leaves the fold. Hungary, however, will now be the site of a new battery factory by CATL. The size of the investment: €7.34 billion (China.Table reported). The fact that this was announced just the day after Latvia and Estonia announced their withdrawal was read by some observers as an indirect reaction to the Baltic exit.

Poland and Romania are growing increasingly skeptical about Chinese investment. In Romania, all Chinese projects have been frozen. In 2020, the Romanians broke off talks with the Chinese about the Cernavoda nuclear power plant after seven years of negotiations. In Poland, the biggest project is the freight railroad running along the Land Silk Road from China. Trains continued to run there despite problems in 2021 on the Polish-Belarusian border and now during the Russian war in Ukraine. The biggest economic problem between Poland and the People’s Republic is the trade deficit. However, skepticism toward China does not seem to be pushing the governments in Warsaw and Bucharest to leave the cooperation format at this time.

The most likely candidate for withdrawal is the Czech Republic. Here, the question is not if, but when the step will be taken, as Ivana Karásková, China Research Fellow at the Association for International Affairs (AMO) in Prague, writes. Since the new Prime Minister Petr Fiala took office, the Czech Republic has been making more critical statements about China. Czech Foreign Minister Jan Lipavský is in favor of closer ties with Taiwan. In addition, the Foreign Ministry echoed the assessment that the format has brought the Czech Republic virtually no benefits over a decade of membership.

The Foreign Affairs Committee of the Czech Chamber of Deputies has already specifically called for withdrawal in a resolution. However, the Czech Republic still has to get rid of one “hurdle”: President Miloš Zeman. Zeman is Beijing’s champion. He personally attended the CEEC-China summit last year online. Since Zeman will not be allowed to run for re-election in January, the Czech Republic is expected to leave 14+1 next year.

Fans of superhero movies in China are on a two-year dry spell. Although China’s movie theaters reopened their doors fairly quickly during the Covid pandemic, Hollywood blockbusters were absent. Global box office hits like Black Widow, Shang Chi and Spider-Man: No Way Home have not made it to the Chinese market.

The gateway for superhero movies is clogged. The new Marvel movie Thor – Love and Thunder joins a long list of unreleased Marvel movies, although Avengers: Endgame grossed more than $629 million in China alone in 2019, a major contributor to the movie’s $2.7 billion worldwide. The release of The Batman in March and this week’s Minions: The Rise Of Gru put movie fans and industry analysts back on a more positive note. However, the trend is moving in a different, clear direction.

There is no official reason why US films are not granted licenses in China. This often leads to wild speculation. In the case of Thor – Love and Thunder, it is speculated that a kiss between two same-sex characters could be the reason. For Spider-Man: No Way Home, the Statue of Liberty was allegedly too often on screen. But this fate also befell non-Marvel movies. For Top Gun: Maverick, the cause was allegedly a Japanese and a Taiwanese flag on Tom Cruise’s flight jacket. However, such speculation cannot be confirmed.

What is new is that movies are more often completely excluded. In the past, censors often cut out the corresponding scenes or ordered content changed using computer effects. Naturally, the non-appearance of the movies does not benefit either side financially.

If previous major Marvel releases are anything to go by, a movie like Spider-Man: No Way Home could have expected revenues in the triple-digit millions. 75 percent of that would have fallen to Chinese contractors. This clearly shows that both sides are losing revenue. And the Chinese cinema market could actually have used the money just as much as the US companies. Cinema markets across the globe have suffered under the Covid crisis. Worldwide, revenues are between 30 and 40 percent below the average figures of the last three years. The difference between the Chinese market and the global market: In China, the numbers are currently declining, while elsewhere they are slowly recovering.

According to a study by Comscore Movies, North America has once again overtaken China as the largest movie market this year. However, the difference is only $3 million. China also seems to shift towards decoupling and strong domestic movie productions. The biggest Chinese box office hits of the past two years were Battle of Lake Changjin (about $900 million) and Battle of Changjin II (about $630 million), both of them patriotic action movies. It is a trend that has been going on for years. The share of US productions in the total revenue of the Chinese market is dropping. While it was 38 percent in 2016, US movies accounted for only 12.3 percent in 2021.

So there is a shift to domestic productions. “There is a huge demand for Chinese content among Chinese viewers,” says an industry insider. “These aren’t necessarily people from Beijing or Shanghai, but Chinese content is extremely popular in smaller cities.” Strained US-China relations further exacerbate this trend. Movies like “Battle of Lake Changjin,” in which the US is portrayed as the enemy, are accordingly booming. The fact that they are also technically well-made means that viewers in modern cities can also appreciate them.

To make matters worse, movies such as Dune or, more recently, The Batman have only attracted few viewers to cinemas. The latter completely bombed on the Chinese market – it made less than $30 million. ” This has dampened interest among movie distributors. They can often make more money with Chinese releases than they would with the extra effort that comes with a US movie.”

The Chinese government also has an interest in protecting Chinese movie companies. Only a little more than 34 foreign blockbusters are allowed to be released on the Chinese market under revenue sharing. In 2021, it was just 20. And sharing part of their revenue is significantly less lucrative for US studios in China than in other markets. After all, compared to the 40 to 50 percent of revenue they earn in other movie markets, they only take about 25 percent in China. And the censorship sword of Damocles hangs over every release.

A situation that is also causing resentment among US studio executives. This is because business with the Chinese side is becoming more and more unpredictable. “We sometimes put a guess in the China column, but more often it is blank or we run two models – with and without China,” a veteran financier told Hollywood Reporter magazine. US studios are no longer dependent on the Chinese market, anyway. “The China market remains at once too great an opportunity to disregard and too unpredictable to rely on,” concludes Rance Pow, President of Artisan Gateway, Asia’s leading film and cinema industry consulting firm.

For US studios, the Chinese market is more of an extra income. But for Chinese companies, it is different. They depend on their market. After all, even the most successful Chinese films generate almost no box-office revenue outside China. Joern Petring/Gregor Koppenburg

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

This week, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) published for the first time a list of details and functionalities of algorithms used in the apps of large Internet corporations such as Tencent, Alibaba, Meituan and ByteDance. In doing so, China’s Internet regulator aims to allow users deeper insight and self-determination and “promote healthy development of Internet information services,” according to officials. Many online platforms base their business model on recommendation algorithms that bind users to their services based on individual data.

Beijing has accused Internet platforms of using algorithms to invade users’ privacy and manipulate their decisions. Consequently, the government passed a law in the spring that allows users to view recommendations made by algorithms within apps and online platforms and even disable them if desired. The law, titled “Internet Information Service Algorithmic Recommendation Management Provisions,” is the first of its kind. No other country allows users to extensively disable algorithms in their apps. (China.Table reported).

The list published by the CAC lists 30 algorithms and provides brief explanations. According to the list, Alibaba’s Taobao e-commerce app, for example, uses a recommendation algorithm that evaluates each user’s visit and search history to recommend products and services. Delivery service Meituan provides details about its algorithm, which is used to estimate delivery times and match drivers’ assignments. The list will be continuously expanded, according to the cyberspace administration. rtr/fpe

After more than a year of boycott, H&M is once again allowed to sell products on the Chinese e-commerce platform Tmall. The Swedish textile retailer, which has a good 14 million subscribers on Tmall, had been removed from Tmall and other online retail sites in March 2021 due to critical statements about the origin of Xinjiang cotton (China.Table reported). Tmall is China’s largest B2C shopping platform with more than 500 million registered users.

In 2020, the fashion group stated that it was “deeply concerned by … accusations of forced labor” in cotton production in China and would no longer source products from Xinjiang. The shitstorm on China’s social media, which flared up just a year later, highlights the risks Western companies face in an increasingly nationalistic China. In the wake of the escalation, H&M was also forced to close around 60 of its stores in China – about 12 percent of its total retail network in China.

Behind closed doors, H&M had been in talks to return, insiders tell Bloomberg. With a share of only 3 percent in the global business, China is not vital to the retailer’s survival. However, the People’s Republic is the largest production site for H&M. fpe

Due to high temperatures and lack of rainfall, the water level on China’s longest river, the Yangtze, has fallen to its lowest ever recorded level. A level of 17.54 meters was measured in Wuhan – six meters below the average of recent years and the lowest level since 1865, as reported by the South China Morning Post. A good third of the Chinese population lives along the Yangtze.

The two largest freshwater lakes in the People’s Republic are recording the lowest levels since 1951. The Poyang and the Dongting are connected to the Yangtze. Smaller rivers have also begun to dry up. Southern China has been experiencing peak temperatures since July. The National Meteorological Center has now issued the highest alert for the entire region for the first time, according to the SCMP. Accordingly, 2022 could become the hottest year since 1961.

While low water levels in Germany have so far mainly caused trouble for barge operators, they pose a threat to power generation in China. In the province of Sichuan, the flow of water into hydroelectric dams has dropped by 50 percent from the historical average, Bloomberg reports. Authorities called on companies to conserve electricity and halt production, according to Reuters. Toyota responded by stopping assembly lines at its plant in the province until Saturday. Volkswagen reported that the local plant only experienced minor shipping delays. Foxconn’s Chengdu plant will also remain closed until Saturday. Producers of lithium, polysilicon, fertilizers and other goods have curtailed production.

Some villages around the Chongqing metropolis experienced a drinking water shortage. The fire department provided residents with fresh water for irrigation and consumption. nib

Shanghai biotech Stemirna Therapeutics has begun a Phase 1 trial for its COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The company has been working on the drug since spring 2021 (China.Table reported). Three other Chinese mRNA vaccines are already undergoing clinical trials. The hope now rests on the four vaccine candidates to break the country out of the lockdown trap. A phase 1 trial will initially test a new agent on a small number of people to determine its effects.

Meanwhile, the number of new Sars-CoV-2 infections is again on the rise in several Chinese regions. This raises new lockdown fears. The trend was most striking on the resort island of Hainan, where authorities identified 1,211 new cases. The total number of new infections was 2,368, with Hainan followed by Tibet and Xinjiang in the statistics. Three new cases were found in Shanghai and four in Beijing. fin

China’s authorities continue to admit critical minds to psychiatric hospitals on a large scale without any medical reasons. The Spanish human rights organization Safeguard Defenders has documented 99 cases of hospitalizations following expressions of opinion. Among them are many signatories of petitions who only used official channels to call for improvement of conditions and were classified as dangerous troublemakers for doing so.

The Ministry of Public Security (PSB) operates its own institutions for this purpose: “compulsory treatment institutions” 强制医疗所, commonly known as Ankang 安康 after their old name. They specialize in “criminal, mentally disturbed subjects”. Those committed are faced with sedation using severe medication, electric shocks, and isolation. Some victims spend more than ten years in such facilities. fin

As a student, Christine Althauser always earned skeptical looks whenever her classes and interests were discussed. Political science – not particularly exciting. But Sinology and Slavic Studies as minors? One year of studies in Taiwan and one in Moscow? That sometimes won her horrified looks.

But Althauser was not discouraged from her fascination with Asia and Eastern Europe. Rightly so, as she reflects today. The expertise she acquired in language, culture, politics and society made her numerous foreign assignments possible in the first place.

In her 34-year career, the German Foreign Office had repeatedly sent Christine Althauser to countries with which she already had contact during her studies: twice to Russia, twice to China. Directly after her attaché training in 1987, she came to the German Embassy in Beijing. This was followed by posts at several European embassies, the Permanent Representation to the European Union, the planning staff of the Federal Ministry of Defense and as head of the crisis prevention unit at the Federal Foreign Office. In between, she also earned her doctorate at the University of Heidelberg and lectured at the University of Freiburg. At the end of the 1990s, she was deployed in Russia.

In 2017 came the posting to Shanghai as Consul General. Althauser already knew the metropolis from previous visits as lively and international. However, everything changed with the first lockdown in Wuhan in 2020. Thus, on the final stop of her active career, she witnessed the city’s journey into Covid state of emergency. Although the situation stabilized over the year, she experienced the harbingers of the particularly strict curfews in 2022. But by then she had already left the post.

One can never be fully prepared for profound turning points such as a pandemic, but Althauser already experienced a similar moment in her past, at the very beginning of her career, in Beijing. At that time, she worked in the cultural department, interacted with writers and was in the midst of the flourishing life of the artistic scene – until dialogue came to a brutal end in 1989. It was then that she realized how defining, fast and radical a supposedly stable situation can change.

Althauser is now officially retired, a title she’s not particularly comfortable with. “They should think about renaming it,” she says. She believes she still has a lot to offer from the expertise she has acquired over all these years. Accordingly, she is still tirelessly on the road; last year alone, she helped monitor elections in Georgia and Serbia and led a diplomats’ course in Berlin. New missions are already lined up.

For Althauser, “the exchange with normal people from everyday life, away from professional involvement,” was always of great importance. One of her favorite memories of Shanghai were the many trips by bicycle and on foot, during which she discovered enchanted nooks and crannies full of hidden stories.

Althauser is concerned that the opportunities for such experiences are increasingly disappearing: “The fewer exchanges there are, the more stereotypes will gain the upper hand.” Christine Althauser has set herself the goal of helping to counteract this trend, especially under difficult conditions. Julius Schwarzwälder

Jing Du took up the position of Digital Marketing Manager at Melchers China in August. The marketing expert wants to break new ground in digital communication at the Bremen-based service provider for market expansion and trade. Jing previously worked for the German Chamber of Commerce Abroad and the German Academic Exchange Service in China, among others.

Uwe Schroeter has moved within the SMS Group from Moscow to Beijing, where he has been responsible for the China region as Chief Operating Officer since July. The SMS Group is an internationally operating company in the field of metallurgical and rolling mill technology with headquarters in Düsseldorf. Schroeter already worked for the company as Vice President Service Division in China between 2010 and 2019.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

The Yuan Wang 5 tracking ship in the port of Hambantota, Sri Lanka. Ships of this design can track missiles such as rockets with their large parabolic antennas. They perform civilian tasks such as monitoring satellite launches; they can also maintain contact with man-made orbital devices outside Chinese territory. However, these vessels can also provide support to the military. The presence of the Chinese ship in the port, which was financed with Silk Road funds, is therefore likely to be seen as another ominous sign of Chinese influence.