The case of two illegal Chinese police stations in the Netherlands and the recent attack of an embassy employee in Manchester show: Regime-critical Chinese are also being harassed in Europe. China is said to operate at least 54 overseas police stations in 30 countries. The Chinese security agencies probably also have embassy staff or overseas students on their payroll. In his analysis, Marcel Grzanna reports, among others, about a Chinese documentary filmmaker who lives in Germany and has to deal with intimidation on a regular basis. The German police cannot help him – as long as no crime has been committed, they are powerless.

But the German state is not powerless regarding investments in critical infrastructure or companies. At least in theory. After the chancellor got his way in the Cosco debacle and made the deal possible, the attention of the media and public has been sharpened. That is how the next case comes into focus: The takeover of a factory of the Dortmund chip manufacturer Elmos by Chinese investors. But there are important differences, explains Finn Mayer-Kuckuk.

If China were to make the unconditional decision to go full steam ahead with climate protection – it would be a huge win for the world. Soon, technologies would be mass-produced and become cheaper. Emissions would be significantly reduced. At first glance, Xi’s climate policy to date appears positive. This is also because climate protection and adaptation to climate change are important factors in the Communist Party’s retention of power. But one should not overestimate Xi’s ambitions. After all, there are also many setbacks, as Nico Beckert illuminates in his climate analysis of Xi’s third term in office.

It is unthinkable today, but there was a time when China’s leaders gave extensive interviews. Behind the walls of Beijing’s Zhongnanhai power center, then-head of state and government Jiang Zemin gave an interview. The interview was conducted by then Welt correspondent and now China.Table columnist Johnny Erling. He dug out exciting video interviews and anecdotes. His conclusion: In the era of Xi Jinping, well-planned staging is everything.

Yang Weidong had plenty to do with the Chinese police in his past. As a documentary filmmaker, he became known for a series of hundreds of interviews that critically examined China’s political and social development. The project increasingly brought him into the focus of the security authorities.

This was nothing new for him. Even after his mother, Ph.D. Xue Yinxian, spilled the beans about doping practices in Chinese sports, the family had to get used to regular visits from the police. For example, in 2007, a year before the Beijing Olympics. Officials warned his mother not to talk about doping in China. A scuffle ensued, during which his father fell on his head and died three months later.

Mother, son, and his wife have been living in Germany for several years. In October 2017, they were granted political asylum. Nevertheless, Yang Weidong still has the Chinese security forces breathing down his neck. Not directly, but through employees of the embassy or consulates, or even through Chinese students abroad. Yang recalls that his wife and he were once closely harassed by young Chinese who told him they knew where he lived.

“The Chinese police are behind such warnings,” Yang suspects in an interview with China.Table. “They want to scare us and wear us down, so we will fold. To do this, they use students, among others, as tools,” he says. Three times in the past twelve months, Yang informed the German police. His mother, his wife, and he himself, feel threatened. But the local authorities are powerless as long as no crime is committed, was the answer. At least the officials promised to increase patrols near the place of residence.

Apparently, the Chinese authorities know about the dissident’s every move in Germany, including reports to the police. In July, Wang Weidong’s brother called from Shandong and advised him to bring his mother back home instead of cooperating with the German authorities.

According to a report by the human rights organization Safeguard Defenders, it is also the result of illegal Chinese police operations abroad that the security forces in the People’s Republic are informed. The organization has so far identified 54 so-called overseas police stations (OPS) of the People’s Republic in 30 countries. It identified nine such sites in Spain alone, where the organization is based. In Germany, it said, one illegal OBPS is based in Frankfurt.

Now Dutch media published details about two stations in Holland. In Amsterdam, two former Chinese police officers from the district-free city of Lishui in Zhejiang are on veiled duty, the TV station RTL reported. In Rotterdam, a former military officer was active in a conventional housing block for security authorities from Fuzhou in southern China, he said. The Dutch Foreign Ministry announced a detailed investigation.

The Safeguard Defenders report that the informal police stations were initially set up to protect overseas Chinese from fraud by their compatriots. There had been a massive increase in cases of fraud by telephone or via the Internet in Chinese expatriate communities in particular. The authorities wanted to persuade the suspects to return to China.

In the period from April 2021 to July 2022 alone, for example, the operation succeeded in attracting around 230,000 Chinese nationals from abroad to the People’s Republic. The Ministry of Public Security, to which the police forces are generally subordinate, had publicly announced in April of this year that the operation was a complete success. The authorities are not only using the support of students or embassy staff, but organizations of the so-called united front (China.Table reported).

This is almost as old as the party itself and is primarily responsible for marginalizing political dissent at home but increasingly abroad as well. Countless Chinese foreign associations in Germany and almost every other country in the world ensure that Chinese expatriates do not step out of line but always represent the party line to the outside world. They are also instrumentalized to gather information from foreign partners and spreading it.

Beijing seems to think itself in the right. Europe is very reluctant to extradite criminals to China, he said. “I don’t see what should be wrong with pressuring criminals to surrender to justice,” a Chinese Foreign Ministry official told the Spanish daily El Correo. Despite the lack of agreements, the People’s Republic of China apparently sees justification enough to break international law.

The authorities, on the other hand, do not publicly communicate the fact that it is by no means only fraudsters who are tracked down abroad, but also political dissidents like Yang Weidong. Dutch media also report on regime critics who have been pressured by the illegal police stations. According to Safeguard Defenders, the methods used clearly violate international human rights laws and the territorial sovereignty of individual countries.

The Interior Ministry in Berlin also clarifies that there is no bilateral agreement between Germany and China on the operation of the ÜPS. But it dodges the question of whether it is aware of the clandestine operations. “The federal government does not tolerate the exercise of foreign state power and, accordingly, Chinese agencies do not have any executive powers on the territory of the Federal Republic of Germany,” it says. “The federal government works to ensure that Chinese diplomatic missions operate within the framework of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations and the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations in their activities in Germany.”

How exactly this is to be achieved remains questionable. With its growing economic importance, China is increasingly claiming the right to break international agreements. This self-image was recently made clear by the Chinese consul general in Manchester (China.Table reported). First, he got physical with a pro-democracy Hong Kong protester. Then he told British media that it was the duty of every diplomat to act that way. After all, he said, his head of state had been insulted.

Just a few days after the decision on Cosco’s stake in a Hamburg port, another potential takeover with Chinese participation sparked a new debate. This time, it is about a plant owned by the Dortmund-based semiconductor manufacturer Elmos. Back in December of last year, the company announced it would cede wafer manufacturing to Swedish-Chinese competitor Silex Microsystems. The government wants to approve the takeover, Handelsblatt reported on Thursday, citing government sources in Berlin. The Elmos takeover requires government approval.

So far, the government sees no problem with the acquisition. There are several good reasons:

The company Elmos is not necessarily booming, although the key data sound promising at first glance. The company specializes in chips used in the automotive industry. One company focus is on components that execute a fixed code. This differentiates them from processors that can execute any code and memory chips that can not execute code at all. They are useful for cars and also inexpensive.

But the plant in Dortmund produces semiconductor components with a structure width of 350 nanometers, which is very large compared to current standards. The technological front just moved to 7-nanometer for high-performance chips. In the automotive industry, chips with a structure width of 90 nanometers are typically used in advanced models, although the segment with over 250 nanometers continues to play a significant role.

However, the approval of the deal would run counter to the trend in the semiconductor business to bring more production back to Europe. The EU and Germany are currently pulling out all the stops to bring more semiconductor production back home. Handing over a plant that produces chips for the battered auto industry, of all things, does not fit into the concept. Moreover, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, sensitivity to dependence on autocracies has greatly increased. More discussions of this kind can be expected in the coming months as the media and politicians expose further examples of the transfer of important assets to foreign powers.

The Taiwanese chip market leader TSMC is in talks about opening a factory in the EU. Among other things, it is expected to produce chip types that will be in demand by the automotive industry in the coming years. One potential site is near Dresden. In Japan, TSMC is already building a plant in cooperation with Sony, with sights on customers such as Toyota and Nissan.

A TSMC factory in Germany would not only be on a different scale than the Elmos factory, it would also play on a completely different level. TSMC is a technology leader with business relationships to industry giants across all sectors. However, suspicion of Chinese partnerships is growing regardless. According to the Handelsblatt report, the German Federal Intelligence Service urges not to hand over the Elmos factory to Silex.

Germany and the EU have even been comparatively open to China so far. The US government under Joe Biden already imposed a blockade against the Chinese semiconductor industry. Not only technology exchange, but also mutual business is hardly possible anymore. Suppliers from third countries are also withdrawing from China in part out of fear of the wrath of the United States. For example, the South Korean manufacturer SK Hynix considers selling off its factory in Wuxi. It is hard to operate without overlapping with US partners. The takeover of a US semiconductor site by a Chinese player would be downright unthinkable now.

The Elmos affair brings back memories of Aixtron, a medium-sized company from Aachen, Germany, which was put up for sale in 2016. The company, previously unknown to the public, was supposed to be sold to the state-owned Fujian Grand Chip Investment Fund from Xiamen for a triple-digit million amount. The German Economy Ministry first approved the takeover. However, a veto from America, an important market for Aixtron, killed the deal. German Economics Minister Sigmar at the time ordered another review of the investment, but this time it was denied.

Aixtron is certainly more valuable and vital than Elmos. But the lesson to be learned from this case was to be much more careful about such transactions, especially since the other big wake-up call in the form of the takeover of the robot manufacturer Kuka came in the same year. These days, by the way, Aixtron is glad to not have been sold to the state-owned financial investor with strategic ulterior motives. The company found its way into the technology future without Chinese money.

At first glance, the climate track record of China’s new and old CP General Secretary Xi Jinping looks highly successful. In his nine and a half years as head of state, China:

But experts warn against overestimating the green ambitions of the new old ruler. They believe that China’s environmental and climate policy under Xi serves to maintain the Communist Party’s hold on power; the decline in carbon emissions is partly due to the Covid crisis; and the economy’s compulsion to grow continues unabated. The coal lobby is still strong. And at the upcoming UN climate summit (COP27), no decisive action is expected to come from China.

Cutting carbon emissions and phasing out coal in the long term “are definitely among the most important items on Xi’s political agenda,” says Nis Gruenberg, an analyst at China think tank Merics. “Xi sees climate change mitigation and adaptation as a condition for the Party’s long-term retention of power and the current form of government.”

Still, since Xi took office in 2013, carbon emissions increased less sharply than in previous years. In the last four quarters, they even decreased slightly (China.Table reported). Coal consumption stabilized – at a high level. And renewable energies are being expanded at a rapid pace.

However, these are all relative achievements. China’s emissions were still nearly 12.2 billion metric tons of CO2 in March 2022, according to calculations by Carbon Brief. In two of the last four quarters, the decline was minimal (see chart). Per capita emissions have been above the EU average since 2018. China is now also historically the world’s second-largest polluter. The tanker has been slowed down but still moves in the wrong direction.

The success of declining carbon emissions is also due in part to the real estate crisis and regular Covid lockdowns. Whether the decrease will continue remains to be seen.

Lauri Myllyvirta and Xing Zhang, China experts at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), are convinced that the rapid expansion of renewables offers a great opportunity. The expansion of renewables could happen at such a fast pace that additional demand for energy over the next few years could be entirely met by clean energy. For this to happen, however, electricity demand must not grow by more than 4 percent per year.

Internally, China considers climate policy to be important. Since the announcement of the climate targets, the central government and the provinces issued more than 60 action plans for the individual sectors. At the international level and COP27, however, there will probably be no new major pledges. Special climate envoy Xie Zhenhua recently said that the implementation and realization of existing climate targets must be the focus at COP (China.Table reported).

So far, Xi Jinping himself does not seek the COP as a big stage. He announced his big climate plans – the 2030/60 targets and the phase-out of coal overseas – before the UN General Assembly. China does not want to be pushed by other countries at the COP, but rather to be perceived as an independent player in front of its domestic audience.

The climate issue must also subordinate itself to Xi’s geopolitical strategy. At COP26 in Glasgow, Chinese delegation leader Xie announced that the People’s Republic would continue climate talks with the United States despite all geopolitical tensions. Six months later, after the controversial Taiwan visit by US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi, China suspended those talks. They could only now possibly be resumed at COP27.

However, China plans to unveil a methane emissions reduction strategy later this year. “This is China’s additional contribution beyond our NDCs,” Xie said in a recent interview. Methane emissions in the oil and gas sector, as well as agriculture and waste disposal, will be “controlled,” Xie said. He did not mention the coal sector, which accounted for the bulk of methane emissions.

Analysts are not overly optimistic that China will move more quickly toward Paris compliance during Xi’s third term in office, either. Renewable energies will probably be expanded even faster. But coal will remain an important part of the energy supply in the medium term. Whether there will be any new momentum in climate protection, however, “will also be driven by realpolitik factors, be it economic crises or international tensions,” Gruenberg says. “The more uncertain the overall situation is, the more uncertain the green transition will be.”

The growing conflicts between China and the USA and the EU could hardly have worse timing. After all, internal debates on China’s next Five-Year Plan will already begin next year. If geopolitical tensions and the Covid and economic crisis in China continue, Beijing’s climate ambitions for the next Five-Year Plan could be low. If China then still fails to name specific figures for the emissions peak by 2030 to preserve climate and industrial policy leeway, the path from 2030 toward carbon neutrality will become even steeper than it is already.

Xi may be China’s most powerful man and has concentrated more and more power on himself over the past decade. But when it comes to climate protection, he cannot and will not dictate. The People’s Republic is still too dependent on coal. Yet the country does have the will, the technical capabilities and the support of its leaders to advance the energy transition faster, Gruenberg said. “This is also one of the goals that are important to Xi Jinping personally,” says the Merics researcher. “But the coal lobby manages to push coal as the safest basis of the energy system every time there is a crisis, whether it’s the heat wave this year or the power crisis in 2021, further delaying the phase-out.”

Reforms to the electricity market have also been too slow, he said. “In this area, China could have achieved a great deal in cutting carbon emissions,” Gruenberg said. Coal has had priority in China’s energy system for years. This is also due to the powerful interests of the coal industry and the provinces. The latter act as a link between the central government and the local level, where climate policy is often implemented. The provinces also pursue their own goals and can, for example, slow down the coal phase-out.

And Xi also must reconcile different goals: Economic growth is the core legitimization of his government and the Communist Party. A secure power supply for industry and climate protection are similarly high on his agenda. In times of crisis, however, growth and energy security take precedence. More than 60 million people are employed in the carbon-heavy sectors of coal, construction and heavy industry (China.Table reported). Xi repeatedly urges cautious change in political speeches. “The new must be created before the old is discarded,” he said at the recent Party Congress regarding China’s energy supply.

31 Oct. 2022, 06:00 p.m. (01:00 a.m. Beijing time)

SOAS China Institute, Webinar: Reinventing the Belt and Road More

02 Nov. 2022, 05:00 p.m. (0:00 a.m. Beijing time)

Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Webinar: Critical Issues Confronting China featuring Winston Ma – Blockchain, Digital Currency, and the Post-20th Party Congress US-China Tech Race More

03 Nov. 2022, 02:20 a.m. (09:20 a.m. Beijing time)

South China Morning Post, Conference: Hong Kong – ASEAN Summit 2022 More

04 Nov. 2022, 03:00 p.m. (10:00 p.m. Beijing time)

Washington International Trade Association, Webinar: No Chips for You! America’s New Export Controls on Semiconductors and Their Implications for Global Trade More

New lockdowns have come into effect in several cities and regions in China. Existing virus containment measures have been tightened. After health authorities reported more than 1,000 new Covid 19 cases on Thursday for the third day in a row, neighborhoods and streets in several cities were sealed off as high-risk areas. In some cases, People are no longer allowed to leave their homes.

Among the municipalities most affected by the lockdown rules are the economically strong Guangzhou in the south, the Covid epicenter Wuhan, and Xining, the capital of Qinghai province. At the beginning of the week, more or less strict lockdowns were in force in 28 Chinese cities. According to analysts at financial institution Nomura, this affected about 207.7 million people in regions that generate about ¥25.6 trillion (about €3.5 trillion), or about a quarter of China’s gross domestic product.

The BBC reports that hundreds of people in Lhasa protested against the strict Covid measures on Wednesday afternoon. The demonstrators were reportedly mostly Han Chinese. The Tibetan capital has been under a lockdown for three months. Protests of this magnitude have not occurred here since 2008. rtr/fpe

According to information from the Financial Times, the situation following the Covid outbreak at the world’s largest iPhone factory in Zhengzhou is more dramatic than previously known. Citing video footage, the newspaper reports that Foxconn employees are already lacking food and medicine. The videos the affected wanted to go public with were deleted by the Chinese authorities.

In the middle of the week, Apple supplier Foxconn declared that it would have to curb production due to 23 Covid cases. In addition, the company closed the plant’s canteens and sealed off the dormitories. About 300,000 employees work at the plant, which is important for Apple. Workers have not been allowed to leave the factory premises for nearly three weeks. According to the Financial Times, several tens of thousands of employees have been infected with Covid. Fpe

Xi Jinping has spoken in favor of better cooperation between the United States and China. This was reported by the Chinese news agency Xinhua. In his congratulatory message at the annual gala dinner of the American National Committee on US-China Relations Foundation, he wrote that China is ready to work with the US in the new era “in mutual respect and peaceful coexistence.” He said that strengthening communication and cooperation between the world powers would help enhance global stability and security and promote world peace and development.

The atmosphere between Beijing and Washington is currently agitated. In addition to the two countries’ far-apart positions on Russia’s war in Ukraine and Taiwan, this is partly due to the US government’s harsh chip regulations. These will have a massive impact on the sector in China and thus represent an obstacle to China’s development (China.Table reported).

Joe Biden also commented on the relationship. In a meeting with US Defense Department officials, he said the US needed to maintain its military lead but did not seek conflict. However, Biden said that the US was seeking competition with China, which could be fierce.

There may be a meeting between the two leaders in a few weeks. Both are expected at the G20 summit in Bali. However, the meeting has not yet been confirmed. Jul

The first passenger aircraft developed entirely in China, Comac C919, will enter service in December. This is reported by the aviation portal Aerotelegraph. According to the report, China Eastern subsidiary OTT will take delivery of the aircraft in mid-December.

Aircraft manufacturer Comac received type certification and thus permission to deliver the aircraft at the end of September, much later than planned. The aircraft made its maiden flight in 2017, and the C919 was actually scheduled to enter service in 2016. In addition to the considerable delays, the price also rose. The aircraft is expected to cost about twice as much as planned, the equivalent of €95 million (China.Table reported). However, this still makes the C919 significantly cheaper than other models in its segment, costing almost 20 percent less than Airbus 320 Neo or Boeing 737 Max.

So far, the company is said to have 815 orders from 28 customers, all from China. The People’s Republic is the world’s largest aircraft market. Experts estimate that the country will need 4,300 new aircraft worth $480 billion over the next two decades. jul

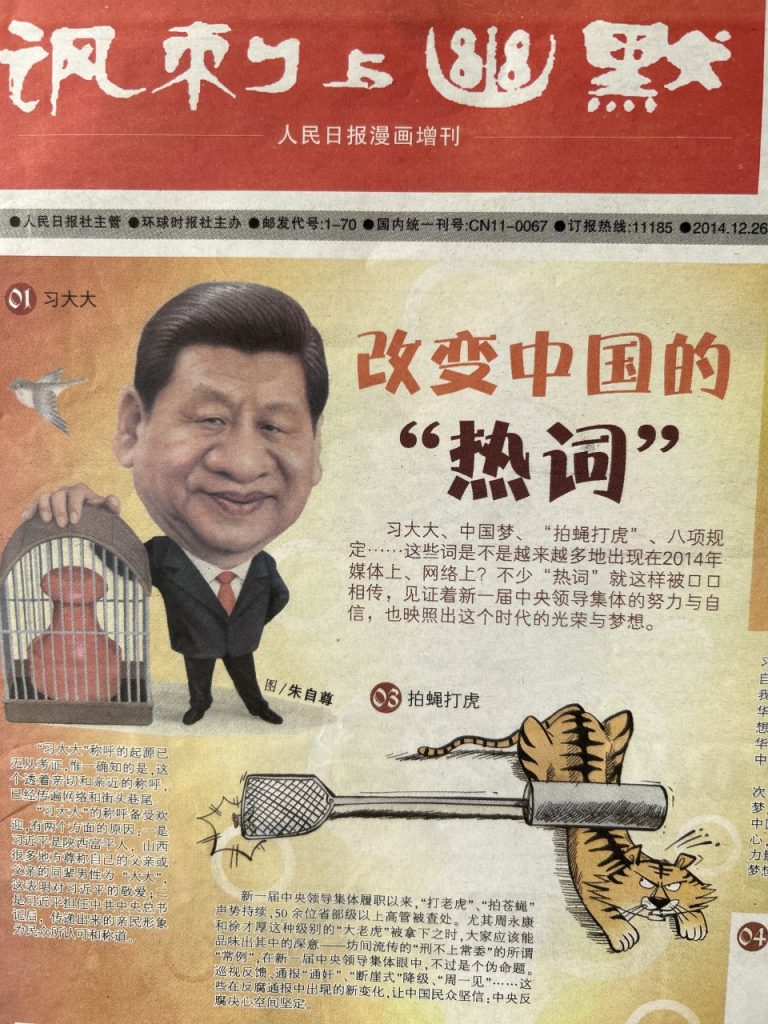

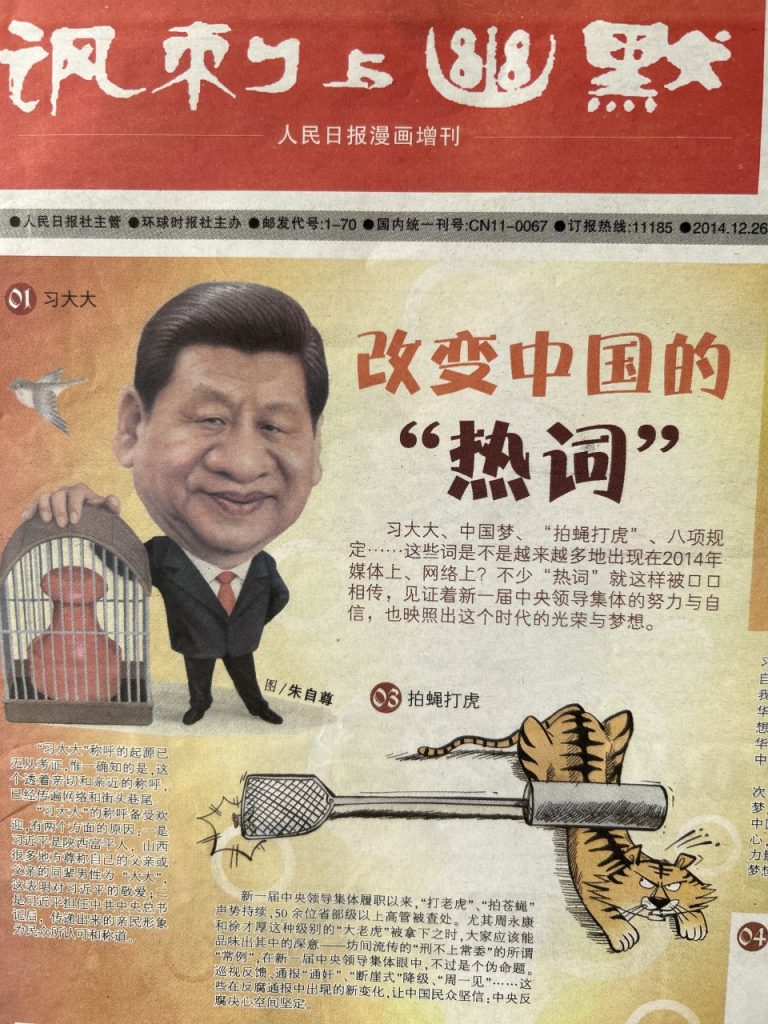

Xi Jinping is commonly described in foreign biographies as “the most powerful man in the world,” even more so since he managed to extend his term for another five years at the 20th Party Congress and fill all important party posts with close followers. For the second time during his time as president, Xi had the party constitution amended and now has all 97 million CP members doubly sworn in to defend him as “the core and at the same time the central authority of the party leadership” (两个维护). Since his unstoppable rise to absolute power, Xi refused all interviews or public dialogues, apparently for fear of exposing himself. Everything is meticulously orchestrated for him, as was evident at the most recent Party Congress, which he prepared down to the last detail, apparently to avoid risks.

The ritualized scene repeats itself every five years. And last Sunday, it played out again in the People’s Congress – certainly not for the last time. Immediately after the end of the 20th Party Congress, the Party leader, who was confirmed for another five years, stepped before the journalists in the hall with six chosen henchmen for his Politburo Standing Committee. Except for Xi’s new inner leadership on the podium, everyone else had to wear a mask because of Covid.

It was his show of undisguised imperial power, with reporters playing only the role of claqueurs. Xi chose the “Golden Hall” of the Great Hall of the People (人民大会堂金色大厅) for the meeting. In 2012 and 2017, the “East Hall” (东大厅) had been sufficient for the self-promoter, with its giant mural of the Great Wall, the symbol of China. This time, he celebrated his appearance, broadcast live on TV, in front of a red background with the Party hammer and sickle emblem. In other words, Xi is the personified power of the Party.

At the end of 2012, he introduced himself as the new Party leader with his men in tow as “primus inter pares”. In 2017, he set himself apart from the collective as the “core” of the leadership. Now, the 69-year-old Xi outgrew all that. The world press wrote “Autocrat Xi,” calling the other Politburo Committee members his “loyalists.” Courageous bloggers mockingly demanded that the committee be renamed the “Xi Secretariat.”

Mistakenly, Xi’s appearance in front of journalists is repeatedly referred to as a press conference. Beijing’s official reading speaks of “meeting with domestic and foreign journalists” (同中外记者见面). Since Xi ascended to China’s party leadership in 2012, the party and state leader has not given press conferences or interviews.

Thus, Xi once again evaded tricky questions from the press, not only those that would have interested foreign countries. In a game of cat and mouse with the censors, courageous Chinese bloggers wanted to know from Xi why he is relying more and more systematically on old networks as his new power base. They listed four of his close associates from his time as Zhejiang provincial chief from 2003 to 2007 whom he lifted into the Party leadership. In addition to Li Qiang (李强) and Cai Qi (蔡奇), who sit on the Politburo Committee, there are Chen Min’er (陈敏尔) and Huang Kunming (黄坤明), who sit on the Politburo. Online, nicknames like Xi’s “Zhejiang Club” or his “Shanghai Faction” are currently causing a furor. A list of the names of 19 senior party officials who dealt with Xi when he was Shanghai party chief in 2007 is circulating online. Three ended up in the Politburo, eight in the Central Committee, seven are CC successors and one is said to be part of the CC disciplinary supervisors.

From the beginning, Xi has been working towards this, directing and overseeing all the preparations, elections, and decisions of the 20th Party Congress. This week, he allowed his propaganda apparatus to reveal amazing things. For example, how the nomination of the 2300 Party Congress delegates took place, the new election of the CC and the CP leaders, or the 50 changes in the Party statutes. The Party agreed on these in eleven working conferences, each of which was chaired by Xi.

He left nothing to chance, nor did he trust internal Party recommendations or nominations. In March 2021, he had a higher-level CC special commission established to review the nomination of all 2300 CP Congress delegates. He made himself its head (2021年3月… 中央政治局会议 决定成立二十大干部考察领导小组,习近平总书记亲自担任组长). Forty-five groups of inspectors from the CC and eight from the Military Commission spent months sifting through the behavior and views of every candidate all over China on his behalf. It was not just about how loyal they are to Xi, but about how committed they are to his cause, to “determine whether they have the courage and are adept at standing up to Western and US sanctions and defending China’s national security.” (注重了解在应对美西方制裁、维护国家安全等问题上是否敢于斗争、善于斗争)

No wonder all the delegates at the Party Congress voted yes. What is even more concerning is that Xinhua reveals how decisions on a person’s appointment and duties depend primarily “on the party’s complete system of standards and perfected procedures, and by no means just on the simple election results.” (党的领导和民主是统一的,不是对立的….不能简单以票取人”…我们党…有一套完整的体制,选人用人标准).

Xi is turning out to be a control freak. That may be the reason why he does not give free interviews to Chinese or foreign reporters, which involve an element of unpredictability. When CCTV surprisingly once showed him at a Q&A session with Russian correspondents in 2017, one participant later revealed to me: They had to submit their questions in advance, which were answered to them in writing by Xi’s office. During a brief photo-op, Xi pretended to hear and answer them for the first time.

In 2014, I witnessed how a journalist spontaneously asked Xi a question during a visit of US President Barack Obama. After eight hours of talks, the two presidents achieved a breakthrough in their climate protection agreement, which had been negotiated for months. The Chinese side agreed that Xi and Obama would answer questions from journalists at the People’s Congress following their statements. It was agreed that a US correspondent would be allowed to question Obama and a Chinese journalist would be allowed to question Xi. As a price for China’s concession, the press conference was not broadcast live on TV.

Thus, the Chinese TV audience missed that New York Times reporter Mark Landler did not abide by the agreement. He first asked Obama, but then suddenly turned to Xi, asking his opinion on the situation in Hong Kong and on China’s residence and visa stops for US journalists disliked by Beijing.

I was sitting a few meters away and saw how Xi was looking for answers. He was playing for time, demanding to hear the next question from a Chinese journalist first, for which he was obviously prepared. After lengthy answers, he responded to Landler in a strange way: “When a car breaks down on the road, its occupants should get out first to see what the problem is.” Then he quoted a proverb: “Let he who tied the bell on the tiger take it off.” It took time for the audience to understand: Those who caused the problem (i.e., angered China) should first look for a solution themselves.

A mix of fear of exposing himself, coupled with the arrogance that Xi, as China’s leader, does not need to give interviews, seems to be why he has not allowed interviews since 2012. His predecessors were different, with Mao Zedong answering Edgar Snow even amid the xenophobic Cultural Revolution. Deng Xiaoping faced two days of probing questions from star journalist Oriana Fallaci in 1980. Such interviews are still an exciting read today.

On May 2, 1990, ten months after the Tiananmen massacre, President Jiang Zemin was not afraid to take a stand in front of US celebrity journalist Barbara Walters and later Mike Wallace on “60 Minutes.” He engaged in a live televised speech duel with US President Bill Clinton at the Great Hall of the People in 1998. I also had the privilege of interviewing Jiang for the German newspaper Die Welt as a Beijing correspondent in 2001, together with my editor-in-chief at the time. That was something special, but normal.

Since the Xi era, everything changed. Yet before 2012, as a provincial leader, he allowed himself to speak openly to Chinese newspapers and local TV stations. But with more and more power, Xi changed. Mindful of his own status, after 2017, he had even positively intended, harmless cartoons banned, although he tolerated them at the beginning of his rise. At the same time, he began to speak and write in increasingly ideological terms. Peter Handke’s proverbial goalkeeper’s fear of penalty seems to set in for the “most powerful man in the world” as soon as it comes to free interviews with the media and feely conducted dialogues.

Alexander Klause has taken on the role of Senior Strategic Buyer for Powertrain and Electric Drive Units at Daimler China. Previously, he was responsible for global procurement management for the eDrive category at Daimler. For his new role, he is moving from Stuttgart to Beijing.

Zhang Youxia and He Weidong were appointed Vice Chairmen of the Central Military Commission on Sunday. Zhang is considered a close ally of Xi Jinping. He joined the army at 18 and served as a company commander during the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War. During Xi’s tenure, Zhang headed the General Armament Department of the People’s Liberation Army, which includes China’s human spaceflight projects. He oversaw the military maneuvers around Taiwan that Beijing ordered in August to protest Nancy Pelosi’s visit. The Central Military Commission is headed by President Xi Jinping, who thus heads China’s two-million-strong People’s Liberation Army.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Anyone who doesn’t bury themselves in the silt very quickly ends up in a basket. In Tangdaowan, on the west coast of Qingdao, hundreds of residents gathered off the coast. They collect oysters, shrimp, and crabs. But the seafood hunt has to be fast before the sea washes over everything after a few hours.

The case of two illegal Chinese police stations in the Netherlands and the recent attack of an embassy employee in Manchester show: Regime-critical Chinese are also being harassed in Europe. China is said to operate at least 54 overseas police stations in 30 countries. The Chinese security agencies probably also have embassy staff or overseas students on their payroll. In his analysis, Marcel Grzanna reports, among others, about a Chinese documentary filmmaker who lives in Germany and has to deal with intimidation on a regular basis. The German police cannot help him – as long as no crime has been committed, they are powerless.

But the German state is not powerless regarding investments in critical infrastructure or companies. At least in theory. After the chancellor got his way in the Cosco debacle and made the deal possible, the attention of the media and public has been sharpened. That is how the next case comes into focus: The takeover of a factory of the Dortmund chip manufacturer Elmos by Chinese investors. But there are important differences, explains Finn Mayer-Kuckuk.

If China were to make the unconditional decision to go full steam ahead with climate protection – it would be a huge win for the world. Soon, technologies would be mass-produced and become cheaper. Emissions would be significantly reduced. At first glance, Xi’s climate policy to date appears positive. This is also because climate protection and adaptation to climate change are important factors in the Communist Party’s retention of power. But one should not overestimate Xi’s ambitions. After all, there are also many setbacks, as Nico Beckert illuminates in his climate analysis of Xi’s third term in office.

It is unthinkable today, but there was a time when China’s leaders gave extensive interviews. Behind the walls of Beijing’s Zhongnanhai power center, then-head of state and government Jiang Zemin gave an interview. The interview was conducted by then Welt correspondent and now China.Table columnist Johnny Erling. He dug out exciting video interviews and anecdotes. His conclusion: In the era of Xi Jinping, well-planned staging is everything.

Yang Weidong had plenty to do with the Chinese police in his past. As a documentary filmmaker, he became known for a series of hundreds of interviews that critically examined China’s political and social development. The project increasingly brought him into the focus of the security authorities.

This was nothing new for him. Even after his mother, Ph.D. Xue Yinxian, spilled the beans about doping practices in Chinese sports, the family had to get used to regular visits from the police. For example, in 2007, a year before the Beijing Olympics. Officials warned his mother not to talk about doping in China. A scuffle ensued, during which his father fell on his head and died three months later.

Mother, son, and his wife have been living in Germany for several years. In October 2017, they were granted political asylum. Nevertheless, Yang Weidong still has the Chinese security forces breathing down his neck. Not directly, but through employees of the embassy or consulates, or even through Chinese students abroad. Yang recalls that his wife and he were once closely harassed by young Chinese who told him they knew where he lived.

“The Chinese police are behind such warnings,” Yang suspects in an interview with China.Table. “They want to scare us and wear us down, so we will fold. To do this, they use students, among others, as tools,” he says. Three times in the past twelve months, Yang informed the German police. His mother, his wife, and he himself, feel threatened. But the local authorities are powerless as long as no crime is committed, was the answer. At least the officials promised to increase patrols near the place of residence.

Apparently, the Chinese authorities know about the dissident’s every move in Germany, including reports to the police. In July, Wang Weidong’s brother called from Shandong and advised him to bring his mother back home instead of cooperating with the German authorities.

According to a report by the human rights organization Safeguard Defenders, it is also the result of illegal Chinese police operations abroad that the security forces in the People’s Republic are informed. The organization has so far identified 54 so-called overseas police stations (OPS) of the People’s Republic in 30 countries. It identified nine such sites in Spain alone, where the organization is based. In Germany, it said, one illegal OBPS is based in Frankfurt.

Now Dutch media published details about two stations in Holland. In Amsterdam, two former Chinese police officers from the district-free city of Lishui in Zhejiang are on veiled duty, the TV station RTL reported. In Rotterdam, a former military officer was active in a conventional housing block for security authorities from Fuzhou in southern China, he said. The Dutch Foreign Ministry announced a detailed investigation.

The Safeguard Defenders report that the informal police stations were initially set up to protect overseas Chinese from fraud by their compatriots. There had been a massive increase in cases of fraud by telephone or via the Internet in Chinese expatriate communities in particular. The authorities wanted to persuade the suspects to return to China.

In the period from April 2021 to July 2022 alone, for example, the operation succeeded in attracting around 230,000 Chinese nationals from abroad to the People’s Republic. The Ministry of Public Security, to which the police forces are generally subordinate, had publicly announced in April of this year that the operation was a complete success. The authorities are not only using the support of students or embassy staff, but organizations of the so-called united front (China.Table reported).

This is almost as old as the party itself and is primarily responsible for marginalizing political dissent at home but increasingly abroad as well. Countless Chinese foreign associations in Germany and almost every other country in the world ensure that Chinese expatriates do not step out of line but always represent the party line to the outside world. They are also instrumentalized to gather information from foreign partners and spreading it.

Beijing seems to think itself in the right. Europe is very reluctant to extradite criminals to China, he said. “I don’t see what should be wrong with pressuring criminals to surrender to justice,” a Chinese Foreign Ministry official told the Spanish daily El Correo. Despite the lack of agreements, the People’s Republic of China apparently sees justification enough to break international law.

The authorities, on the other hand, do not publicly communicate the fact that it is by no means only fraudsters who are tracked down abroad, but also political dissidents like Yang Weidong. Dutch media also report on regime critics who have been pressured by the illegal police stations. According to Safeguard Defenders, the methods used clearly violate international human rights laws and the territorial sovereignty of individual countries.

The Interior Ministry in Berlin also clarifies that there is no bilateral agreement between Germany and China on the operation of the ÜPS. But it dodges the question of whether it is aware of the clandestine operations. “The federal government does not tolerate the exercise of foreign state power and, accordingly, Chinese agencies do not have any executive powers on the territory of the Federal Republic of Germany,” it says. “The federal government works to ensure that Chinese diplomatic missions operate within the framework of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations and the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations in their activities in Germany.”

How exactly this is to be achieved remains questionable. With its growing economic importance, China is increasingly claiming the right to break international agreements. This self-image was recently made clear by the Chinese consul general in Manchester (China.Table reported). First, he got physical with a pro-democracy Hong Kong protester. Then he told British media that it was the duty of every diplomat to act that way. After all, he said, his head of state had been insulted.

Just a few days after the decision on Cosco’s stake in a Hamburg port, another potential takeover with Chinese participation sparked a new debate. This time, it is about a plant owned by the Dortmund-based semiconductor manufacturer Elmos. Back in December of last year, the company announced it would cede wafer manufacturing to Swedish-Chinese competitor Silex Microsystems. The government wants to approve the takeover, Handelsblatt reported on Thursday, citing government sources in Berlin. The Elmos takeover requires government approval.

So far, the government sees no problem with the acquisition. There are several good reasons:

The company Elmos is not necessarily booming, although the key data sound promising at first glance. The company specializes in chips used in the automotive industry. One company focus is on components that execute a fixed code. This differentiates them from processors that can execute any code and memory chips that can not execute code at all. They are useful for cars and also inexpensive.

But the plant in Dortmund produces semiconductor components with a structure width of 350 nanometers, which is very large compared to current standards. The technological front just moved to 7-nanometer for high-performance chips. In the automotive industry, chips with a structure width of 90 nanometers are typically used in advanced models, although the segment with over 250 nanometers continues to play a significant role.

However, the approval of the deal would run counter to the trend in the semiconductor business to bring more production back to Europe. The EU and Germany are currently pulling out all the stops to bring more semiconductor production back home. Handing over a plant that produces chips for the battered auto industry, of all things, does not fit into the concept. Moreover, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, sensitivity to dependence on autocracies has greatly increased. More discussions of this kind can be expected in the coming months as the media and politicians expose further examples of the transfer of important assets to foreign powers.

The Taiwanese chip market leader TSMC is in talks about opening a factory in the EU. Among other things, it is expected to produce chip types that will be in demand by the automotive industry in the coming years. One potential site is near Dresden. In Japan, TSMC is already building a plant in cooperation with Sony, with sights on customers such as Toyota and Nissan.

A TSMC factory in Germany would not only be on a different scale than the Elmos factory, it would also play on a completely different level. TSMC is a technology leader with business relationships to industry giants across all sectors. However, suspicion of Chinese partnerships is growing regardless. According to the Handelsblatt report, the German Federal Intelligence Service urges not to hand over the Elmos factory to Silex.

Germany and the EU have even been comparatively open to China so far. The US government under Joe Biden already imposed a blockade against the Chinese semiconductor industry. Not only technology exchange, but also mutual business is hardly possible anymore. Suppliers from third countries are also withdrawing from China in part out of fear of the wrath of the United States. For example, the South Korean manufacturer SK Hynix considers selling off its factory in Wuxi. It is hard to operate without overlapping with US partners. The takeover of a US semiconductor site by a Chinese player would be downright unthinkable now.

The Elmos affair brings back memories of Aixtron, a medium-sized company from Aachen, Germany, which was put up for sale in 2016. The company, previously unknown to the public, was supposed to be sold to the state-owned Fujian Grand Chip Investment Fund from Xiamen for a triple-digit million amount. The German Economy Ministry first approved the takeover. However, a veto from America, an important market for Aixtron, killed the deal. German Economics Minister Sigmar at the time ordered another review of the investment, but this time it was denied.

Aixtron is certainly more valuable and vital than Elmos. But the lesson to be learned from this case was to be much more careful about such transactions, especially since the other big wake-up call in the form of the takeover of the robot manufacturer Kuka came in the same year. These days, by the way, Aixtron is glad to not have been sold to the state-owned financial investor with strategic ulterior motives. The company found its way into the technology future without Chinese money.

At first glance, the climate track record of China’s new and old CP General Secretary Xi Jinping looks highly successful. In his nine and a half years as head of state, China:

But experts warn against overestimating the green ambitions of the new old ruler. They believe that China’s environmental and climate policy under Xi serves to maintain the Communist Party’s hold on power; the decline in carbon emissions is partly due to the Covid crisis; and the economy’s compulsion to grow continues unabated. The coal lobby is still strong. And at the upcoming UN climate summit (COP27), no decisive action is expected to come from China.

Cutting carbon emissions and phasing out coal in the long term “are definitely among the most important items on Xi’s political agenda,” says Nis Gruenberg, an analyst at China think tank Merics. “Xi sees climate change mitigation and adaptation as a condition for the Party’s long-term retention of power and the current form of government.”

Still, since Xi took office in 2013, carbon emissions increased less sharply than in previous years. In the last four quarters, they even decreased slightly (China.Table reported). Coal consumption stabilized – at a high level. And renewable energies are being expanded at a rapid pace.

However, these are all relative achievements. China’s emissions were still nearly 12.2 billion metric tons of CO2 in March 2022, according to calculations by Carbon Brief. In two of the last four quarters, the decline was minimal (see chart). Per capita emissions have been above the EU average since 2018. China is now also historically the world’s second-largest polluter. The tanker has been slowed down but still moves in the wrong direction.

The success of declining carbon emissions is also due in part to the real estate crisis and regular Covid lockdowns. Whether the decrease will continue remains to be seen.

Lauri Myllyvirta and Xing Zhang, China experts at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), are convinced that the rapid expansion of renewables offers a great opportunity. The expansion of renewables could happen at such a fast pace that additional demand for energy over the next few years could be entirely met by clean energy. For this to happen, however, electricity demand must not grow by more than 4 percent per year.

Internally, China considers climate policy to be important. Since the announcement of the climate targets, the central government and the provinces issued more than 60 action plans for the individual sectors. At the international level and COP27, however, there will probably be no new major pledges. Special climate envoy Xie Zhenhua recently said that the implementation and realization of existing climate targets must be the focus at COP (China.Table reported).

So far, Xi Jinping himself does not seek the COP as a big stage. He announced his big climate plans – the 2030/60 targets and the phase-out of coal overseas – before the UN General Assembly. China does not want to be pushed by other countries at the COP, but rather to be perceived as an independent player in front of its domestic audience.

The climate issue must also subordinate itself to Xi’s geopolitical strategy. At COP26 in Glasgow, Chinese delegation leader Xie announced that the People’s Republic would continue climate talks with the United States despite all geopolitical tensions. Six months later, after the controversial Taiwan visit by US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi, China suspended those talks. They could only now possibly be resumed at COP27.

However, China plans to unveil a methane emissions reduction strategy later this year. “This is China’s additional contribution beyond our NDCs,” Xie said in a recent interview. Methane emissions in the oil and gas sector, as well as agriculture and waste disposal, will be “controlled,” Xie said. He did not mention the coal sector, which accounted for the bulk of methane emissions.

Analysts are not overly optimistic that China will move more quickly toward Paris compliance during Xi’s third term in office, either. Renewable energies will probably be expanded even faster. But coal will remain an important part of the energy supply in the medium term. Whether there will be any new momentum in climate protection, however, “will also be driven by realpolitik factors, be it economic crises or international tensions,” Gruenberg says. “The more uncertain the overall situation is, the more uncertain the green transition will be.”

The growing conflicts between China and the USA and the EU could hardly have worse timing. After all, internal debates on China’s next Five-Year Plan will already begin next year. If geopolitical tensions and the Covid and economic crisis in China continue, Beijing’s climate ambitions for the next Five-Year Plan could be low. If China then still fails to name specific figures for the emissions peak by 2030 to preserve climate and industrial policy leeway, the path from 2030 toward carbon neutrality will become even steeper than it is already.

Xi may be China’s most powerful man and has concentrated more and more power on himself over the past decade. But when it comes to climate protection, he cannot and will not dictate. The People’s Republic is still too dependent on coal. Yet the country does have the will, the technical capabilities and the support of its leaders to advance the energy transition faster, Gruenberg said. “This is also one of the goals that are important to Xi Jinping personally,” says the Merics researcher. “But the coal lobby manages to push coal as the safest basis of the energy system every time there is a crisis, whether it’s the heat wave this year or the power crisis in 2021, further delaying the phase-out.”

Reforms to the electricity market have also been too slow, he said. “In this area, China could have achieved a great deal in cutting carbon emissions,” Gruenberg said. Coal has had priority in China’s energy system for years. This is also due to the powerful interests of the coal industry and the provinces. The latter act as a link between the central government and the local level, where climate policy is often implemented. The provinces also pursue their own goals and can, for example, slow down the coal phase-out.

And Xi also must reconcile different goals: Economic growth is the core legitimization of his government and the Communist Party. A secure power supply for industry and climate protection are similarly high on his agenda. In times of crisis, however, growth and energy security take precedence. More than 60 million people are employed in the carbon-heavy sectors of coal, construction and heavy industry (China.Table reported). Xi repeatedly urges cautious change in political speeches. “The new must be created before the old is discarded,” he said at the recent Party Congress regarding China’s energy supply.

31 Oct. 2022, 06:00 p.m. (01:00 a.m. Beijing time)

SOAS China Institute, Webinar: Reinventing the Belt and Road More

02 Nov. 2022, 05:00 p.m. (0:00 a.m. Beijing time)

Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Webinar: Critical Issues Confronting China featuring Winston Ma – Blockchain, Digital Currency, and the Post-20th Party Congress US-China Tech Race More

03 Nov. 2022, 02:20 a.m. (09:20 a.m. Beijing time)

South China Morning Post, Conference: Hong Kong – ASEAN Summit 2022 More

04 Nov. 2022, 03:00 p.m. (10:00 p.m. Beijing time)

Washington International Trade Association, Webinar: No Chips for You! America’s New Export Controls on Semiconductors and Their Implications for Global Trade More

New lockdowns have come into effect in several cities and regions in China. Existing virus containment measures have been tightened. After health authorities reported more than 1,000 new Covid 19 cases on Thursday for the third day in a row, neighborhoods and streets in several cities were sealed off as high-risk areas. In some cases, People are no longer allowed to leave their homes.

Among the municipalities most affected by the lockdown rules are the economically strong Guangzhou in the south, the Covid epicenter Wuhan, and Xining, the capital of Qinghai province. At the beginning of the week, more or less strict lockdowns were in force in 28 Chinese cities. According to analysts at financial institution Nomura, this affected about 207.7 million people in regions that generate about ¥25.6 trillion (about €3.5 trillion), or about a quarter of China’s gross domestic product.

The BBC reports that hundreds of people in Lhasa protested against the strict Covid measures on Wednesday afternoon. The demonstrators were reportedly mostly Han Chinese. The Tibetan capital has been under a lockdown for three months. Protests of this magnitude have not occurred here since 2008. rtr/fpe

According to information from the Financial Times, the situation following the Covid outbreak at the world’s largest iPhone factory in Zhengzhou is more dramatic than previously known. Citing video footage, the newspaper reports that Foxconn employees are already lacking food and medicine. The videos the affected wanted to go public with were deleted by the Chinese authorities.

In the middle of the week, Apple supplier Foxconn declared that it would have to curb production due to 23 Covid cases. In addition, the company closed the plant’s canteens and sealed off the dormitories. About 300,000 employees work at the plant, which is important for Apple. Workers have not been allowed to leave the factory premises for nearly three weeks. According to the Financial Times, several tens of thousands of employees have been infected with Covid. Fpe

Xi Jinping has spoken in favor of better cooperation between the United States and China. This was reported by the Chinese news agency Xinhua. In his congratulatory message at the annual gala dinner of the American National Committee on US-China Relations Foundation, he wrote that China is ready to work with the US in the new era “in mutual respect and peaceful coexistence.” He said that strengthening communication and cooperation between the world powers would help enhance global stability and security and promote world peace and development.

The atmosphere between Beijing and Washington is currently agitated. In addition to the two countries’ far-apart positions on Russia’s war in Ukraine and Taiwan, this is partly due to the US government’s harsh chip regulations. These will have a massive impact on the sector in China and thus represent an obstacle to China’s development (China.Table reported).

Joe Biden also commented on the relationship. In a meeting with US Defense Department officials, he said the US needed to maintain its military lead but did not seek conflict. However, Biden said that the US was seeking competition with China, which could be fierce.

There may be a meeting between the two leaders in a few weeks. Both are expected at the G20 summit in Bali. However, the meeting has not yet been confirmed. Jul

The first passenger aircraft developed entirely in China, Comac C919, will enter service in December. This is reported by the aviation portal Aerotelegraph. According to the report, China Eastern subsidiary OTT will take delivery of the aircraft in mid-December.

Aircraft manufacturer Comac received type certification and thus permission to deliver the aircraft at the end of September, much later than planned. The aircraft made its maiden flight in 2017, and the C919 was actually scheduled to enter service in 2016. In addition to the considerable delays, the price also rose. The aircraft is expected to cost about twice as much as planned, the equivalent of €95 million (China.Table reported). However, this still makes the C919 significantly cheaper than other models in its segment, costing almost 20 percent less than Airbus 320 Neo or Boeing 737 Max.

So far, the company is said to have 815 orders from 28 customers, all from China. The People’s Republic is the world’s largest aircraft market. Experts estimate that the country will need 4,300 new aircraft worth $480 billion over the next two decades. jul

Xi Jinping is commonly described in foreign biographies as “the most powerful man in the world,” even more so since he managed to extend his term for another five years at the 20th Party Congress and fill all important party posts with close followers. For the second time during his time as president, Xi had the party constitution amended and now has all 97 million CP members doubly sworn in to defend him as “the core and at the same time the central authority of the party leadership” (两个维护). Since his unstoppable rise to absolute power, Xi refused all interviews or public dialogues, apparently for fear of exposing himself. Everything is meticulously orchestrated for him, as was evident at the most recent Party Congress, which he prepared down to the last detail, apparently to avoid risks.

The ritualized scene repeats itself every five years. And last Sunday, it played out again in the People’s Congress – certainly not for the last time. Immediately after the end of the 20th Party Congress, the Party leader, who was confirmed for another five years, stepped before the journalists in the hall with six chosen henchmen for his Politburo Standing Committee. Except for Xi’s new inner leadership on the podium, everyone else had to wear a mask because of Covid.

It was his show of undisguised imperial power, with reporters playing only the role of claqueurs. Xi chose the “Golden Hall” of the Great Hall of the People (人民大会堂金色大厅) for the meeting. In 2012 and 2017, the “East Hall” (东大厅) had been sufficient for the self-promoter, with its giant mural of the Great Wall, the symbol of China. This time, he celebrated his appearance, broadcast live on TV, in front of a red background with the Party hammer and sickle emblem. In other words, Xi is the personified power of the Party.

At the end of 2012, he introduced himself as the new Party leader with his men in tow as “primus inter pares”. In 2017, he set himself apart from the collective as the “core” of the leadership. Now, the 69-year-old Xi outgrew all that. The world press wrote “Autocrat Xi,” calling the other Politburo Committee members his “loyalists.” Courageous bloggers mockingly demanded that the committee be renamed the “Xi Secretariat.”

Mistakenly, Xi’s appearance in front of journalists is repeatedly referred to as a press conference. Beijing’s official reading speaks of “meeting with domestic and foreign journalists” (同中外记者见面). Since Xi ascended to China’s party leadership in 2012, the party and state leader has not given press conferences or interviews.

Thus, Xi once again evaded tricky questions from the press, not only those that would have interested foreign countries. In a game of cat and mouse with the censors, courageous Chinese bloggers wanted to know from Xi why he is relying more and more systematically on old networks as his new power base. They listed four of his close associates from his time as Zhejiang provincial chief from 2003 to 2007 whom he lifted into the Party leadership. In addition to Li Qiang (李强) and Cai Qi (蔡奇), who sit on the Politburo Committee, there are Chen Min’er (陈敏尔) and Huang Kunming (黄坤明), who sit on the Politburo. Online, nicknames like Xi’s “Zhejiang Club” or his “Shanghai Faction” are currently causing a furor. A list of the names of 19 senior party officials who dealt with Xi when he was Shanghai party chief in 2007 is circulating online. Three ended up in the Politburo, eight in the Central Committee, seven are CC successors and one is said to be part of the CC disciplinary supervisors.

From the beginning, Xi has been working towards this, directing and overseeing all the preparations, elections, and decisions of the 20th Party Congress. This week, he allowed his propaganda apparatus to reveal amazing things. For example, how the nomination of the 2300 Party Congress delegates took place, the new election of the CC and the CP leaders, or the 50 changes in the Party statutes. The Party agreed on these in eleven working conferences, each of which was chaired by Xi.

He left nothing to chance, nor did he trust internal Party recommendations or nominations. In March 2021, he had a higher-level CC special commission established to review the nomination of all 2300 CP Congress delegates. He made himself its head (2021年3月… 中央政治局会议 决定成立二十大干部考察领导小组,习近平总书记亲自担任组长). Forty-five groups of inspectors from the CC and eight from the Military Commission spent months sifting through the behavior and views of every candidate all over China on his behalf. It was not just about how loyal they are to Xi, but about how committed they are to his cause, to “determine whether they have the courage and are adept at standing up to Western and US sanctions and defending China’s national security.” (注重了解在应对美西方制裁、维护国家安全等问题上是否敢于斗争、善于斗争)

No wonder all the delegates at the Party Congress voted yes. What is even more concerning is that Xinhua reveals how decisions on a person’s appointment and duties depend primarily “on the party’s complete system of standards and perfected procedures, and by no means just on the simple election results.” (党的领导和民主是统一的,不是对立的….不能简单以票取人”…我们党…有一套完整的体制,选人用人标准).

Xi is turning out to be a control freak. That may be the reason why he does not give free interviews to Chinese or foreign reporters, which involve an element of unpredictability. When CCTV surprisingly once showed him at a Q&A session with Russian correspondents in 2017, one participant later revealed to me: They had to submit their questions in advance, which were answered to them in writing by Xi’s office. During a brief photo-op, Xi pretended to hear and answer them for the first time.

In 2014, I witnessed how a journalist spontaneously asked Xi a question during a visit of US President Barack Obama. After eight hours of talks, the two presidents achieved a breakthrough in their climate protection agreement, which had been negotiated for months. The Chinese side agreed that Xi and Obama would answer questions from journalists at the People’s Congress following their statements. It was agreed that a US correspondent would be allowed to question Obama and a Chinese journalist would be allowed to question Xi. As a price for China’s concession, the press conference was not broadcast live on TV.

Thus, the Chinese TV audience missed that New York Times reporter Mark Landler did not abide by the agreement. He first asked Obama, but then suddenly turned to Xi, asking his opinion on the situation in Hong Kong and on China’s residence and visa stops for US journalists disliked by Beijing.

I was sitting a few meters away and saw how Xi was looking for answers. He was playing for time, demanding to hear the next question from a Chinese journalist first, for which he was obviously prepared. After lengthy answers, he responded to Landler in a strange way: “When a car breaks down on the road, its occupants should get out first to see what the problem is.” Then he quoted a proverb: “Let he who tied the bell on the tiger take it off.” It took time for the audience to understand: Those who caused the problem (i.e., angered China) should first look for a solution themselves.

A mix of fear of exposing himself, coupled with the arrogance that Xi, as China’s leader, does not need to give interviews, seems to be why he has not allowed interviews since 2012. His predecessors were different, with Mao Zedong answering Edgar Snow even amid the xenophobic Cultural Revolution. Deng Xiaoping faced two days of probing questions from star journalist Oriana Fallaci in 1980. Such interviews are still an exciting read today.

On May 2, 1990, ten months after the Tiananmen massacre, President Jiang Zemin was not afraid to take a stand in front of US celebrity journalist Barbara Walters and later Mike Wallace on “60 Minutes.” He engaged in a live televised speech duel with US President Bill Clinton at the Great Hall of the People in 1998. I also had the privilege of interviewing Jiang for the German newspaper Die Welt as a Beijing correspondent in 2001, together with my editor-in-chief at the time. That was something special, but normal.

Since the Xi era, everything changed. Yet before 2012, as a provincial leader, he allowed himself to speak openly to Chinese newspapers and local TV stations. But with more and more power, Xi changed. Mindful of his own status, after 2017, he had even positively intended, harmless cartoons banned, although he tolerated them at the beginning of his rise. At the same time, he began to speak and write in increasingly ideological terms. Peter Handke’s proverbial goalkeeper’s fear of penalty seems to set in for the “most powerful man in the world” as soon as it comes to free interviews with the media and feely conducted dialogues.

Alexander Klause has taken on the role of Senior Strategic Buyer for Powertrain and Electric Drive Units at Daimler China. Previously, he was responsible for global procurement management for the eDrive category at Daimler. For his new role, he is moving from Stuttgart to Beijing.

Zhang Youxia and He Weidong were appointed Vice Chairmen of the Central Military Commission on Sunday. Zhang is considered a close ally of Xi Jinping. He joined the army at 18 and served as a company commander during the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War. During Xi’s tenure, Zhang headed the General Armament Department of the People’s Liberation Army, which includes China’s human spaceflight projects. He oversaw the military maneuvers around Taiwan that Beijing ordered in August to protest Nancy Pelosi’s visit. The Central Military Commission is headed by President Xi Jinping, who thus heads China’s two-million-strong People’s Liberation Army.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Anyone who doesn’t bury themselves in the silt very quickly ends up in a basket. In Tangdaowan, on the west coast of Qingdao, hundreds of residents gathered off the coast. They collect oysters, shrimp, and crabs. But the seafood hunt has to be fast before the sea washes over everything after a few hours.