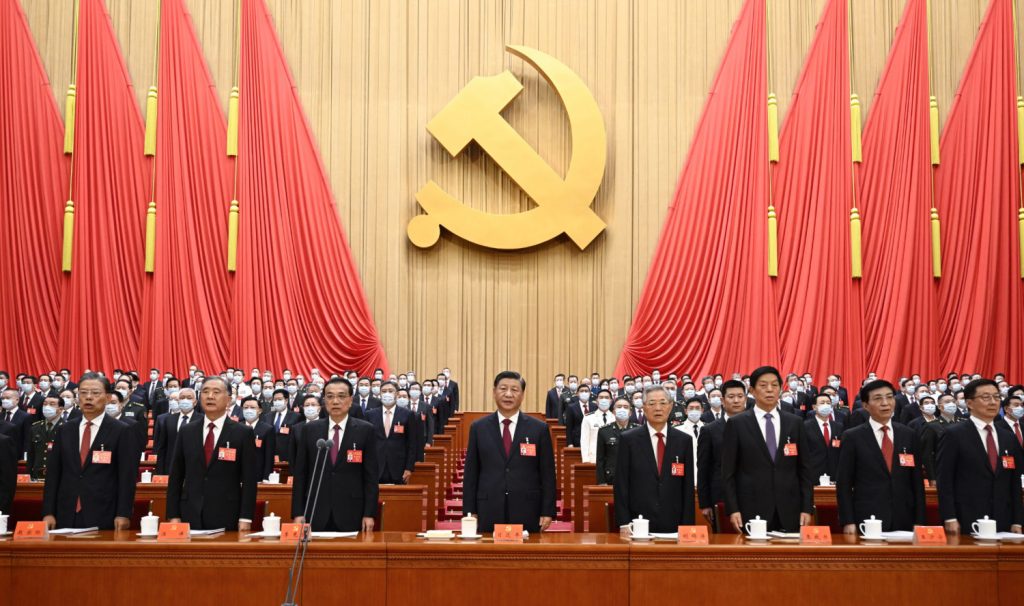

The 20th Party Congress of the Communist Party of China has started. Since 2018, it has been clear that it would be a landmark event. At the time, Xi Jinping arranged for the ten-year presidential term limit to be lifted. The real taboo break, the execution of the coup thus prepared from within, follows now. Xi will have himself reelected this week beyond the formerly valid term limit. The already rudimentary system of internal party control is thus finally undermined.

The global position that Xi wants China to achieve is even a historical first, analyzes Frank Sieren. Under Xi, for the first time, the country has laid claim to shaping the world. To this end, Xi is rearming – and renewing his threats against Taiwan.

He also gave words of warning to the CP. He eliminated “latent dangers” within the party, Xi said. Dangers, clearly: To his own position of power. But no one really challenges his power. Even if commentators on social media believe they constantly find new indications of infighting among the leadership, none of this is dangerous for Xi at this time.

This also goes for the protest at the Xitong Bridge, whose traces have been erased from the Chinese Internet. The lone protester already has a nickname: “Bridge Man“. Find out more in our analysis. The question now is: Will there be imitators? Could this even give rise to a protest movement? Not likely. But who knows.

A true threat to the Party comes from a different direction. Xi seems to be confident that the economy will somehow keep going. He knows the hardships of the Mao era, but during his political career, economic planners always managed to create growth when needed. Is this why he perhaps believes the economy can endure every zero-Covid extreme? In any case, he defended his policies in his speech at the party congress. In an analysis and guest article, we turn our attention to the future prospects for China’s shaky economy.

In his opening speech to the 20th Party Congress, Xi Jinping makes it clear that China will no longer shy away and make itself smaller than it is, as the great reformer Deng Xiaoping once insisted. Deng chose Xi’s predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao himself. Xi, on the other hand, had to fight his way to the top.

Now he is finally stepping out of Deng’s shadow. “China’s international influence, appeal and power to shape the world has significantly increased,” Xi told the 2,300 delegates. This is not only a new tone for the People’s Republic, but also a first in Chinese history. Although the emperors of the Middle Kingdom considered China to be the center of the world and all other countries to be vassals filled with barbarians, they traditionally never laid claim to shaping the world.

At the previous Party Congress in 2017, Xi said “China stands tall and firm in the East.” Now he was more self-assured and power-conscious, both in terms of himself and China’s position in the world. In the face of “drastic changes” in the global landscape, China has shown “firm strategic resolve” and demonstrated a “fighting spirit,” Xi said in his speech.

The Party “safeguarded China’s dignity and core interests and kept ourselves well-positioned for pursuing development and ensuring security.” This part of his speech, again, sounds a bit more defensive because it is primarily about China’s own development, which no one, including the West, should stand in the way of. The goal is not to impose its will on the world.

But then new bold, some would even say nationalistic, tones are again heard: “Chinese modernization offers humanity a new choice for achieving modernization.” However, Xi also emphasizes that China will never strive for hegemony.

The powerful party leader also explains the path China’s modernization should take. His first priority is “common prosperity.” The Chinese should be able to achieve this by “more pay for more work.” This is not a socialist strategy, but rather a free-market one.

The party will “steadfastly” encourage the expansion of the private sector and provide support and guidance to market participants. The “crucial” role of the market in the “allocation of resources” has been recognized. Government, he said, must play a better role in setting the framework for the market. People will “achieve prosperity through hard work,” as Xi puts it in one sentence, which will be supported by “equality of opportunity.” That is the economic liberal aspect of his policy.

To accomplish this, however, China must simultaneously raise the wages of those who earn the least and thus “expand the size of the middle income group.” However, the Party will “keep income distribution and the means of accumulating wealth well regulated.” That is the socialist part of his policy. So Xi will continue to oppose forms of Manchester capitalism and the monopolies of large corporations.

There has also been “overwhelming progress” in the fight against corruption. “Corruption is the biggest cancer.” On national security, he does not show composure: “We must resolutely pursue a holistic approach to national security,” Xi said.

He also emphasized environmental policy and climate goals, by working “actively and prudently toward the goals of reaching peak carbon emissions and carbon neutrality.”

In important industries such as IT, but also real estate (which he did not mention), Xi has specified new rules that should bring more equality of opportunity. This means painful cuts at first, but in the end more choice for customers through more competitors.

Xi at the same time emphasized how important the high-tech industry is for China’s rise. Science and research are the most important production force, skilled labor the most important resource, and innovation “the most important driving force” for China’s rise. Last year, China spent $388 billion on research and development.

The head of state made clear how highly he values innovation and entrepreneurship. “Without solid material and technology foundation,” it would be impossible to build a strong socialist country. Overall, Xi speaks of “high-quality growth.” This means that the days of growth at any price are over.

Observers eagerly awaited what Xi would say on the issue of continuing zero-Covid. Indeed, he went on the offensive. “We put the people and their lives above all else,” Xi defended his policy.

The country made “tremendously encouraging achievements,” both in fighting the epidemic and in “economic and social development.” Indeed, unlike the West, China does not have double-digit inflation, only 2.5 percent. Yet the economy continues to slump dramatically thanks to lockdowns and entry restrictions. For Xi, however, there is obviously still no reason to give a clear signal in his speech toward relaxing his Covid policy.

One hint of where things are maybe headed is when Xi emphasized, “development is the top priority” for the Party. However, he did not use the “top priority” label for zero-Covid. And Xi again clarifies that China maintains its commitment to “high-quality opening” to foreign investors.

By now, at the latest, it is clear that Xi’s speech aims to take a sweeping approach. Short-term political control, as his attitude suggests, has no place at this party congress, which takes place only every five years.

This also applies to the Taiwan issue. Xi continues to speak of the goal of “peaceful reunification with the greatest sincerely and the utmost effort.” But this sentence is followed, as always, by the very decisive qualification: “We will never promise to renounce the use of force.” When that might happen is left open by Xi. What is not open is the goal: “The complete reunification of our country must be realized and it can without a doubt be realized.”

In this context, Xi announces that he will expand the military strength of his troops. He wants to modernize the strategic military command and develop concepts for a “people’s war,” including “a strong system of strategic deterrence.”

This issue gained weight compared to 2017, which is probably not only a result of the confrontation between China and the US, but also of the war in Ukraine. Xinjiang goes unmentioned by Xi. Regarding Hong Kong, Xi is confident of victory: It was “ensured that Hong Kong is governed by patriots,” and “Order has been restored.” This was “a major turn for the better in the region.”

Overall, Xi calls China’s path a “self-revolution.” The party owes its success to socialism with Chinese characteristics, to “Marxism and the way China has adapted it.”

His speech makes it clear that Xi wants to continue to balance contradictory political goals such as economic growth with greater social equality on the one hand and zero-Covid on the other. On the one hand, he needs to create jobs; on the other, he needs to meet climate targets.

How and if the balance might shift in his third term, however, is something Xi left open in his speech. He leaves that to the government, whose new prime minister will probably not be decided until the end of this 20th Party Congress.

The action of a democracy activist at the Sitong Bridge in Beijing continues to echo. On the one hand, he is only one of 1.4 billion Chinese – and there is no sign of a mass movement. Theoretically, he could be pretty alone with his opinion, with only the support of a small circle of politically interested intellectuals.

On the other hand, this act has enormous symbolic value. The man has proven: Even fully monitored Beijing cannot always be controlled. That alone shows the limits of the Party’s domination over physical reality. In this first noticeable protest in years, it also became clear that Chinese civil society is not completely dormant. The smoke over the Sitong Bridge could also be seen as a sign of a brewing fire beneath the seemingly sealed surface of society. On top of that, the international media got their scoop ahead of a dull party congress.

On Thursday, the protester unfurled several banners at the road bridge in the Haidian district. He called Xi Jingping a dictator and demanded, among other things, freedom instead of lockdowns, dignity instead of lies and elections instead of a supreme leader. But equally remarkable was how he organized the protest. He had dressed up as a construction worker, pulled up in an official-looking van, and reportedly even requested the help of police officers present to secure his “construction site”. After he had calmly put up the banners, he set the fire to draw additional attention to them. This kind of ingenuity is particularly successful in China, and word travels fast whenever the authorities have been tricked.

Numerous universities and tech companies are dotted around the bridge. The area is teeming with members of the younger generation, who film everything of interest with their smartphones. As a result, the censors had their hands full. Blocked keywords at times included “fire,” “Sitong Bridge,” “brave,” “banner,” and even “Third Ring,” one of Beijing’s main streets.

The man was given the nickname “Bridge Man” on the Internet, based on the “Tank Man” who stood up to the tanks in 1989. The Twitter community in particular was quickly certain that it had identified him. His identity is said to be that of the physicist Peng Lifa. A strong indication of this: On the German science portal ResearchGate, the same protest slogans were published under his account at the same time as the action, neatly edited for sharing. Peng also owns a stake in a Beijing materials company.

Moreover, the same Peng Lifa has disappeared since Thursday, indicating his authorship. Bridge Man was arrested without resistance after the police officers discovered the message on his banners. He could now face torture, prison, and might even disappear.

All Beijing bridges are now under double surveillance, but any copycats would probably choose other places and forms to continue the protest. In the coming weeks, we will see whether his act created any sparks in the minds of other young people and spread the fire. Because smartphone cameras are everywhere, and the chaotic nature of the Internet, more protests would quickly receive attention. Perhaps the Internet is more than just the ingenious instrument of control that the CP has lately used it as. Maybe it is also a potential threat to absolute power.

The Chinese customs office was supposed to publish the trade figures for the month of September on Friday. But apparently, shortly before the CP Congress, negative reports were not welcome: In any case, for the time being, the statistics have not been published and no reasons have been given.

After all, the true extent of the crisis the Chinese economy currently faces is obvious, even without the latest batch of official data. For the first time in 30 years, economists estimate that growth in the People’s Republic has fallen below the Asian average; for the current calendar year, the World Bank predicts an expansion in gross domestic product of only 2.8 percent. It is possible that China will have to get used to such a figure in the medium term.

What sounds respectable for many OECD countries is a near disaster for the Middle Kingdom: Every year, the country must integrate more than ten million university graduates into the labor market, and in addition, the monthly disposable income of around 600 million Chinese is still only the equivalent of €150. The promise of wealth keeps them in line.

The biggest liability for the slow economic growth is unmistakably the dogmatic zero-Covid policy, which continues to dominate the lives of the 1.4 billion Chinese in the third year of the pandemic. Just how much the measures are also affecting businesses is reflected in comments made by business representatives. “Citizens are getting nervous again,” says Francis Liekens, who heads the Shanghai office of the European Chamber of Commerce (EUCC): “It’s a bit like playing roulette: Every time you ask yourself whether you should really leave your apartment or enter a certain building.” Because an unexpected lockdown could be waiting at any time. People have recently been locked up in several office towers and shopping malls in the financial metropolis after a Covid case was detected there.

Harald Kumpfert from the EUCC office in northeastern Shenyang says, “We don’t see much effort for vaccination campaigns.” Instead, he says, everything has long been about mandatory PCR testing. “It has obviously become a huge business. Some of our Chamber of Commerce partners get tested up to four times a day – every time they leave the city limits or the highway.” His colleague Christoph Schrempp from the Tianjin office reports, “The other day we had a Covid outbreak at a company with 20 cases. By 6:30 AM, the entire neighborhood was cordoned off.”

And another business representative from Chengdu tells us with a smug undertone that he had to spend four days in quarantine before his latest external appointment in a neighboring city. And that was just to spend an hour negotiating with his business partners. Chinese entrepreneurs also have to put up with such hassles. It is clear that the economy is not running smoothly.

For outsiders who do not live in China, such statements may seem increasingly surreal. Even a high-ranking medical doctor, who is currently on home leave in Europe and asked to remain anonymous, speaks of a “collective psychosis.” But Xi Jinping defended zero-Covid in his party congress speech as a national struggle that will, of course, continue.

For companies, this may sound downright mocking, but there will be no open criticism from Chinese board members for fear of repression. The consequences of the measures have long been visible to the naked eye: In Beijing, even the once most popular shopping malls are eerily empty on most weekdays, and in Shanghai, the number of people sleeping on the streets has also increased yet again.

Presumably, these are not typical homeless people, but rather migrant workers residing in the surrounding areas who are afraid to enter their homes for fear of a lockdown – and the resulting loss of their source of income.

But zero-Covid is not the only reason for the current economic woes. The real estate market no longer fulfills its function as an economic engine. Previously, it had always been possible to pump money into the housing and construction sectors to stimulate the economy. However, its bubbles have grown too large, and some of the companies have become bankrupt. Attempts to stimulate the sector are clashing with ones to consolidate it. So Xi cannot rely on his economic experts to bring him growth in the tried and true way. Fabian Kretschmer

US citizens will no longer be allowed to be involved in the development or production of microchips in China without obtaining a special license first. This is according to new export control regulations issued by US authorities last week. Previously, US citizens were already prohibited from supporting the development, manufacture or maintenance of weapons in certain countries, particularly nuclear and biological and chemical weapons. The new articles on chip manufacturing target China specifically.

The ban follows the Chips Act passed in July, with which the US government wants to massively promote semiconductor development and production in the United States. In early October, the US government also imposed export bans on American chips and manufacturing equipment to China. The background to this is that US semiconductors are not to be sold to Chinese state-affiliated companies. Microchips are particularly relevant for military and surveillance technologies.

The new regulation could have a massive impact on China’s tech world. According to the financial magazine Nikkei Asia, hundreds of entrepreneurs and developers in the field are US citizens of Chinese descent. Many have studied in the US, gained work experience there at major tech companies, and hold US citizenship. Among them is founder and CEO Gerald Yin of Advanced Micro-Fabrication Equipment Inc. China (AMEC), China’s leading chipmaker, who spent 20 years working in Silicon Valley. Also a US citizen is David H. Wang, CEO of ACM Research.

Building an independent chip ecosystem is of strategic importance to China. Experts believe the US bans could set China’s chip industry back years. jul

Germany’s President Frank-Walter Steinmeier has come under fire for a congratulatory letter to China’s President Xi Jinping. Steinmeier personally wished Xi “happiness and good health” on the occasion of the anniversary of German-Chinese relations last week. In the letter, the German president stressed the importance of “inalienable human rights” and that he wants to “work for the dignity and rights of every human being.” However, the fact that human rights violations in China had not been directly addressed now earned Steinmeier criticism from several political groups. In an interview with the German tabloid Bild, FDP liberal foreign policy expert Frank Mueller-Rosentritt called the congratulatory letter “a slap in the face for all friends of freedom, including those in China.”

In general, certain diplomatic phrases are dictated for letters on such occasions. Steinmeier did not deviate from other congratulatory letters. Friendly messages in which critical issues are avoided are nothing unusual, even between systemic rivals.

Green Party European politician Reinhard Bütikofer appeased that Steinmeier had “thankfully not left out the topic of human rights, even if he addresses it carefully.” According to the report, the Office of the Federal President rejected any criticism: Steinmeier “not only highlighted the joint successes of the past five decades, but at the same time clearly and critically addressed the challenges of the present.” ari

Sri Lanka hopes for a concession from China regarding the repayment of its loans. The country’s president, Ranil Wickremesingh, expressed optimism over the weekend to Reuters that a restructuring of the debt could be reached. Previously, Wickremesingh held talks with China’s Minister of Finance Liu Kun.

China is Sri Lanka’s biggest bilateral lender (China.Table reported). The island nation with 22 million inhabitants currently faces its worst economic crisis in decades. It has debts of around €30 billion. Besides China, the biggest lenders include Japan and India. rtr/jul

BMW denied a media report suggesting the company plans to move production of its electric Mini from the United Kingdom to China. A spokesman for the automaker said on Friday evening that no such move was planned. The Times newspaper previously reported that BMW planned to move production of the car to the People’s Republic. BMW produces about 40,000 electric minis a year at a factory on the outskirts of Oxford. rtr

Xi Jinping is poised to become the first three-term president in Chinese history when the Communist Party of China’s 20th National Congress convenes this month. That makes this an opportune time to take stock of Xi’s economic-policy record from the past ten years and explore some obvious steps to improve economic performance in the next term.

When Xi assumed China’s top political position in 2012, the economy was thriving, but it also had many serious problems. GDP had been growing at an average annual rate of 10% for over a decade. But a slowdown was inevitable, and GDP growth rates have indeed declined almost every year since 2008. Moreover, inequality was rising, with the Gini index having increased by 13 percent between 1990 and 2000. By the start of this century, inequality in China had surpassed that of the United States for the first time in the post-1978 reform era.

Meanwhile, pollution was literally killing China. By 2013, Beijing’s air had an average of 102 micrograms of PM2.5 particles per cubic meter, whereas Los Angeles – a city historically known for its air pollution – had a PM2.5 reading of only around 15. Chinese city dwellers increasingly complained about the cardiopulmonary illnesses and early mortality associated with pollution. And China was also plagued by water pollution, owing to the chemical runoff from its factories, farms, and mines. In rural areas, entire villages and towns sometimes had to move because their water supply had been irreparably contaminated.

China was also gradually losing its workforce. Historically high fertility rates of around six children per woman started to decline in the 1970s and reached their current levels of under two children per women in 2000. China’s working-age cohort shrank from 80 percent of the total population in 1970 to only 37 percent in 2012. The share of individuals over age 65 doubled, from 4 percent in 1970 to 8 percent in 2012. These trends left the government stuck between a rock and a hard place. Though policymakers needed to keep the overall population from ballooning further, they also needed to maintain the supply of young working people to support the growing elderly population.

Social discontent was rising and, according to one popular index, public perceptions of government corruption had doubled between 1991 and 2012. Around 1,300 labor strikes were documented in 2014; by 2016, that figure had more than doubled, to 2,700.

When Xi came to power, he took great pains to confront these challenges head-on. But the results have been mixed. On a positive note, PM2.5 readings in major cities like Beijing and Shanghai have been halved over the past ten years, and China’s Gini coefficient today is back below that of the US and 13 percent below its 2010 peak.

But other indicators are less favorable. Between 2012 and the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s annual GDP growth rate has either remained flat or declined. Even though the government has abolished its stringent one-child policy, fertility rates have remained very low. The share of individuals aged 65 and older today is nearly 13 percent, a new peak for the modern era. And ten years after Xi launched a highly touted anti-corruption campaign, public perceptions of corruption are higher than ever.

Still, it would be misleading to lay all of the past decade’s accomplishments and failures at Xi’s feet. Xi inherited the biggest problems he has faced, which were the unavoidable consequences of China’s previous rapid growth and political and economic history. At the same time, Xi also inherited the main policy solutions to these problems.

After all, China started requiring state-owned energy grids to invest in renewable industries all the way back in 1994, and earlier governments also emphasized policies to improve conditions for the poor. Basic medical insurance was introduced to urban areas in 1998 and to rural areas in 2003. Aggregate inequality began to decline two years prior to Xi taking office, and earlier governments regularly pursued their own anti-corruption drives.

As Xi continued many of his predecessors’ policy initiatives, the things that were improving continued to improve, and the problems that were hard to fix remained unfixed. What changed most under Xi was not the ostensible policy aims but the mode of implementation. With a few exceptions, such as the one-child policy, post-1978 Chinese policymakers before Xi tended to be cautious and discreet. Important changes, like the introduction of rural elections, were usually piloted quietly and only announced as a “national policy” when the central government felt confident that it understood how the policy would work.

This trial-and-error method had the advantage of creating political space for deliberation among important stakeholders, leading to the success of highly complex initiatives such as China’s national health policy. It also allowed for flexibility, with policies being revised to account for changing conditions or unforeseen side effects. And because these policies were not associated with any one person, the political costs of admitting mistakes were low.

Xi has dispensed with such subtleties, announcing policies personally, suddenly, and without much, if any, apparent deliberation. This modus operandi has clearly been economically harmful, even when the motivations behind the policies are benign or well-meaning.

Consider the 2021 ban on private tutoring, which was intended to curb the punishing hours that Chinese children spend studying and to reduce wealthier students’ advantages over their peers. But the rollout was so blunt and sudden that it reduced major Chinese education companies’ market capitalizations by tens of billions of dollars and simply created a black market for the same services. The economic ramifications reach beyond education. The possibility of sudden and unanticipated policy changes discourages future investments in all sectors.

Another example is Xi’s zero-COVID policy. Though it was very successful in keeping the coronavirus at bay when there were no vaccines, it has fared poorly with changing conditions. While all other countries are shifting back to business as usual – or have already done so – China seems stuck in an endless game of Whac-a-Mole.

The implications for the Chinese economy are clear: the authorities should stay the course in terms of economic-policy goals, but change their policymaking methods. Moving slowly and cautiously served China well for more than 40 years. It could work well for many more.

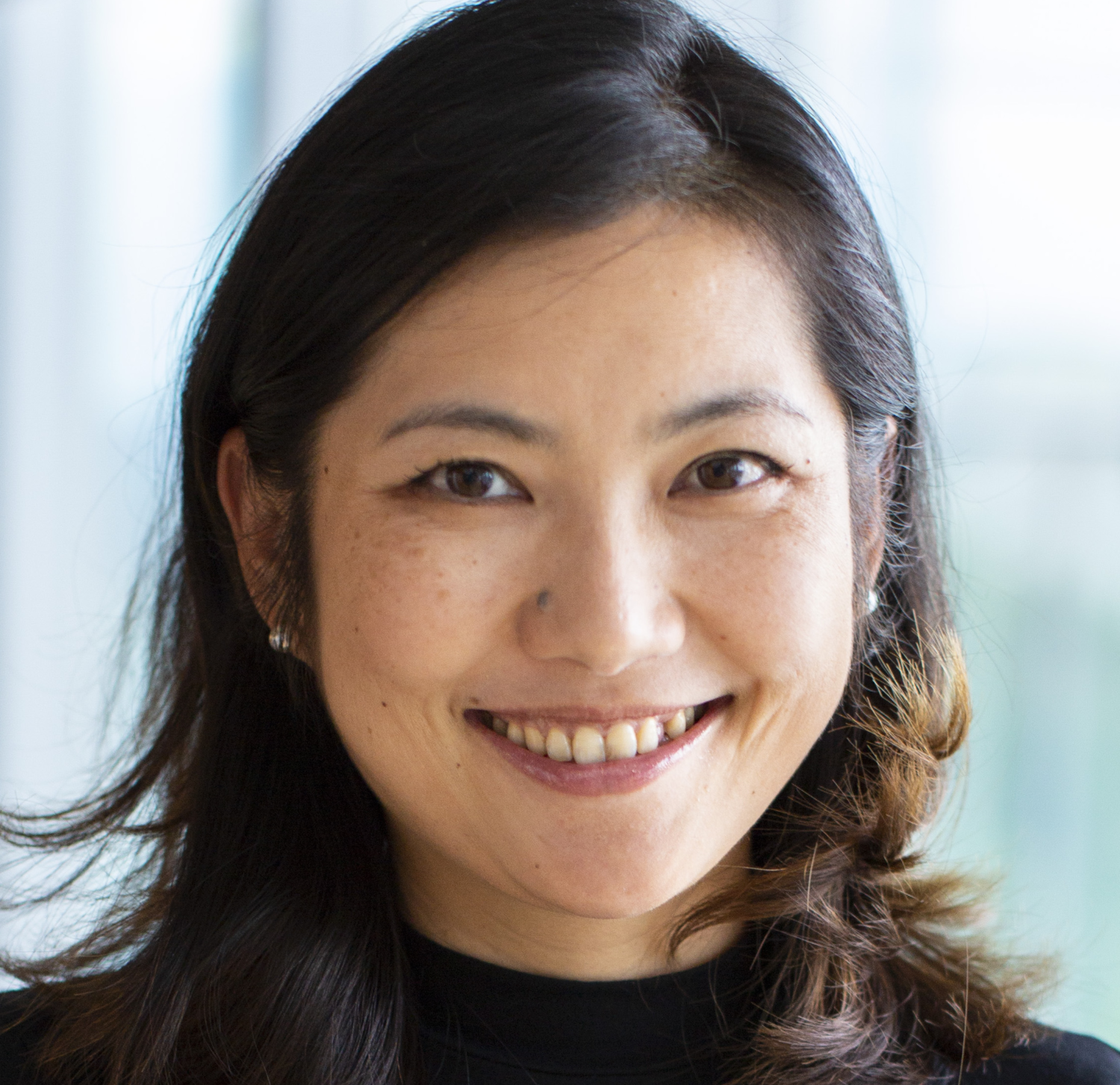

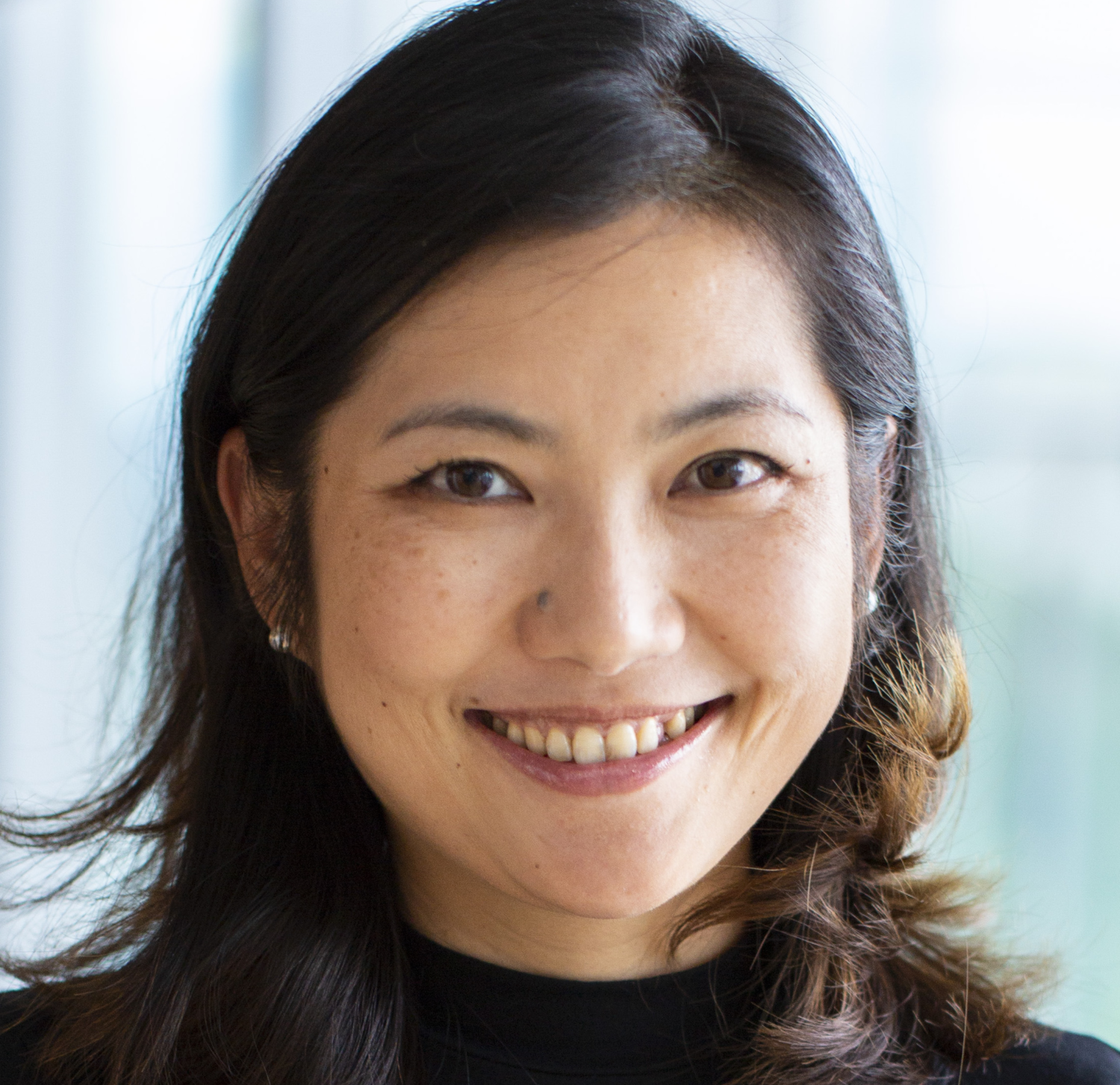

Nancy Qian, Professor of Managerial Economics and Decision Sciences at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, is a co-director of Northwestern University’s Global Poverty Research Lab and the Founding Director of China Econ Lab.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2022.

www.project-syndicate.org

Robin Mallick is the new director of the Goethe-Institut in Beijing. Mallick previously served as head of the Goethe-Institut in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. His predecessor Clemens Treter (China.Table already introduced him in a Profile) is now Goethe-Institut director in Seoul and, as the new director, looks after the entire East Asia region.

Jason Shen is the new Country Manager China at the German medical technology company Medi-Globe Group. The company from Bavaria’s Chiemgau region opened a branch office in Beijing to coordinate its expansion locally.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Lovers in China are willing to “trade an entire universe for a small adzuki bean” (一整个宇宙换一颗红豆 yī zhěnggè yǔzhòu huàn yī kē hóngdòu). At least, that’s how singer Fish Leong (梁静茹Liáng Jìngrú) originally sang it in her 2009 song “Love Song” (情歌 qínggē). The boy band beaus of “Mayday” (五月天 Wǔyuètiān) from Taiwan already wondered in their 2005 hit “John Lennon” how “a red bean wants to single-handedly shoulder the weight of the universe” (一颗红豆为何想单挑这宇宙 yī kē hóngdòu wèihé xiǎng dāntiāo zhè yǔzhòu). And China’s music queen Faye Wong (王菲 Wáng Fēi) straight up named an entire song after the blood-red mini bean.

We are talking about the adzuki bean, in Chinese 赤豆 chìdòu or 红豆 hóngdòu, literally “red bean”. It is found in many song lyrics, novels, and poetry lines in the Middle Kingdom, where its deep red color and long shelf life make it a symbol of longing between lovers (相思 xiāngsī), which is why it is sometimes called the “bean of desire” (相思豆xiāngsīdòu).

But we also encounter these red beans in China in candy stores and bakeries, at steamed bun stalls, and on frozen food shelves. Thanks to their sweet, nutty flavor, they are a popular ingredient in many traditional desserts, but also in many creative new ones, especially as a sweetened paste.

This “red bean paste” (红豆沙 hóngdòushā, literally “red bean sand”), a purple mush made from boiled and then mashed adzuki beans, usually sweetened with sugar or honey, gives many Chinese desserts their characteristic flavor. Originally, the dark paste originated in China’s vegetarian Buddhist cuisine, from which it started its triumphal march to other parts of Asia.

In China, “dousha” is added, among other things, as a filling to the glutinous rice balls Tangyuan (汤圆 tāngyuán), which are traditionally served at the end of the Spring Festival, as well as to the glutinous rice dumplings Zongzi (粽子 zòngzi) wrapped in banana leaves, which are eaten at the Dragon Boat Festival. It is also hard to imagine the mid-autumn festival without the classic moon cakes (月饼 yuèbǐng). Adzuki flavor is also popular in sweet baozi steamed buns (豆沙包 dòushābāo), breakfast cakes fried in fat (豆沙烧饼 dòushā shāobǐng), and sweet spring rolls.

But that is not all: China’s supermarkets now also feature adzuki bean ice cream (红豆冰淇淋 hóngdòu bīngqílín), bean paste croissants (红豆馅牛角面包 hóngdòuxiàn niújiǎo-miànbāo), red bean drink packets (红豆饮料 hóngdòu yǐnliào), adzuki bean milk tea (红豆奶茶 hóngdòu nǎichá) and many other delicious food creations.

While not everyone may be willing to trade an entire universe for an adzuki bean, nothing speaks against getting these – from a Western perspective unconventional – treats for a few yuan the next time you visit China. After all, once you’ve acquired a taste for them, a small universe of new snacks will open up to you.

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.

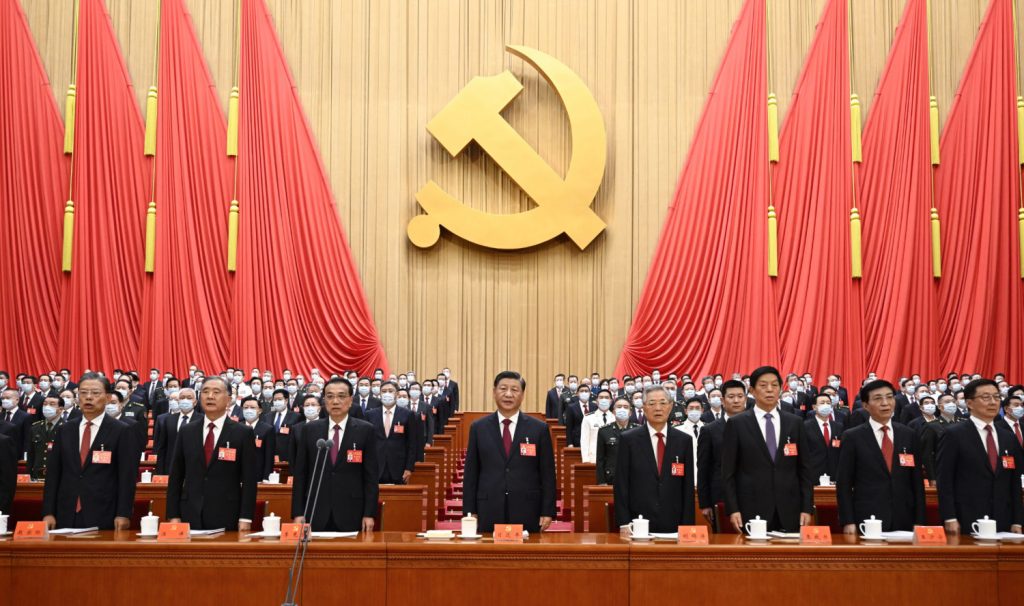

The 20th Party Congress of the Communist Party of China has started. Since 2018, it has been clear that it would be a landmark event. At the time, Xi Jinping arranged for the ten-year presidential term limit to be lifted. The real taboo break, the execution of the coup thus prepared from within, follows now. Xi will have himself reelected this week beyond the formerly valid term limit. The already rudimentary system of internal party control is thus finally undermined.

The global position that Xi wants China to achieve is even a historical first, analyzes Frank Sieren. Under Xi, for the first time, the country has laid claim to shaping the world. To this end, Xi is rearming – and renewing his threats against Taiwan.

He also gave words of warning to the CP. He eliminated “latent dangers” within the party, Xi said. Dangers, clearly: To his own position of power. But no one really challenges his power. Even if commentators on social media believe they constantly find new indications of infighting among the leadership, none of this is dangerous for Xi at this time.

This also goes for the protest at the Xitong Bridge, whose traces have been erased from the Chinese Internet. The lone protester already has a nickname: “Bridge Man“. Find out more in our analysis. The question now is: Will there be imitators? Could this even give rise to a protest movement? Not likely. But who knows.

A true threat to the Party comes from a different direction. Xi seems to be confident that the economy will somehow keep going. He knows the hardships of the Mao era, but during his political career, economic planners always managed to create growth when needed. Is this why he perhaps believes the economy can endure every zero-Covid extreme? In any case, he defended his policies in his speech at the party congress. In an analysis and guest article, we turn our attention to the future prospects for China’s shaky economy.

In his opening speech to the 20th Party Congress, Xi Jinping makes it clear that China will no longer shy away and make itself smaller than it is, as the great reformer Deng Xiaoping once insisted. Deng chose Xi’s predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao himself. Xi, on the other hand, had to fight his way to the top.

Now he is finally stepping out of Deng’s shadow. “China’s international influence, appeal and power to shape the world has significantly increased,” Xi told the 2,300 delegates. This is not only a new tone for the People’s Republic, but also a first in Chinese history. Although the emperors of the Middle Kingdom considered China to be the center of the world and all other countries to be vassals filled with barbarians, they traditionally never laid claim to shaping the world.

At the previous Party Congress in 2017, Xi said “China stands tall and firm in the East.” Now he was more self-assured and power-conscious, both in terms of himself and China’s position in the world. In the face of “drastic changes” in the global landscape, China has shown “firm strategic resolve” and demonstrated a “fighting spirit,” Xi said in his speech.

The Party “safeguarded China’s dignity and core interests and kept ourselves well-positioned for pursuing development and ensuring security.” This part of his speech, again, sounds a bit more defensive because it is primarily about China’s own development, which no one, including the West, should stand in the way of. The goal is not to impose its will on the world.

But then new bold, some would even say nationalistic, tones are again heard: “Chinese modernization offers humanity a new choice for achieving modernization.” However, Xi also emphasizes that China will never strive for hegemony.

The powerful party leader also explains the path China’s modernization should take. His first priority is “common prosperity.” The Chinese should be able to achieve this by “more pay for more work.” This is not a socialist strategy, but rather a free-market one.

The party will “steadfastly” encourage the expansion of the private sector and provide support and guidance to market participants. The “crucial” role of the market in the “allocation of resources” has been recognized. Government, he said, must play a better role in setting the framework for the market. People will “achieve prosperity through hard work,” as Xi puts it in one sentence, which will be supported by “equality of opportunity.” That is the economic liberal aspect of his policy.

To accomplish this, however, China must simultaneously raise the wages of those who earn the least and thus “expand the size of the middle income group.” However, the Party will “keep income distribution and the means of accumulating wealth well regulated.” That is the socialist part of his policy. So Xi will continue to oppose forms of Manchester capitalism and the monopolies of large corporations.

There has also been “overwhelming progress” in the fight against corruption. “Corruption is the biggest cancer.” On national security, he does not show composure: “We must resolutely pursue a holistic approach to national security,” Xi said.

He also emphasized environmental policy and climate goals, by working “actively and prudently toward the goals of reaching peak carbon emissions and carbon neutrality.”

In important industries such as IT, but also real estate (which he did not mention), Xi has specified new rules that should bring more equality of opportunity. This means painful cuts at first, but in the end more choice for customers through more competitors.

Xi at the same time emphasized how important the high-tech industry is for China’s rise. Science and research are the most important production force, skilled labor the most important resource, and innovation “the most important driving force” for China’s rise. Last year, China spent $388 billion on research and development.

The head of state made clear how highly he values innovation and entrepreneurship. “Without solid material and technology foundation,” it would be impossible to build a strong socialist country. Overall, Xi speaks of “high-quality growth.” This means that the days of growth at any price are over.

Observers eagerly awaited what Xi would say on the issue of continuing zero-Covid. Indeed, he went on the offensive. “We put the people and their lives above all else,” Xi defended his policy.

The country made “tremendously encouraging achievements,” both in fighting the epidemic and in “economic and social development.” Indeed, unlike the West, China does not have double-digit inflation, only 2.5 percent. Yet the economy continues to slump dramatically thanks to lockdowns and entry restrictions. For Xi, however, there is obviously still no reason to give a clear signal in his speech toward relaxing his Covid policy.

One hint of where things are maybe headed is when Xi emphasized, “development is the top priority” for the Party. However, he did not use the “top priority” label for zero-Covid. And Xi again clarifies that China maintains its commitment to “high-quality opening” to foreign investors.

By now, at the latest, it is clear that Xi’s speech aims to take a sweeping approach. Short-term political control, as his attitude suggests, has no place at this party congress, which takes place only every five years.

This also applies to the Taiwan issue. Xi continues to speak of the goal of “peaceful reunification with the greatest sincerely and the utmost effort.” But this sentence is followed, as always, by the very decisive qualification: “We will never promise to renounce the use of force.” When that might happen is left open by Xi. What is not open is the goal: “The complete reunification of our country must be realized and it can without a doubt be realized.”

In this context, Xi announces that he will expand the military strength of his troops. He wants to modernize the strategic military command and develop concepts for a “people’s war,” including “a strong system of strategic deterrence.”

This issue gained weight compared to 2017, which is probably not only a result of the confrontation between China and the US, but also of the war in Ukraine. Xinjiang goes unmentioned by Xi. Regarding Hong Kong, Xi is confident of victory: It was “ensured that Hong Kong is governed by patriots,” and “Order has been restored.” This was “a major turn for the better in the region.”

Overall, Xi calls China’s path a “self-revolution.” The party owes its success to socialism with Chinese characteristics, to “Marxism and the way China has adapted it.”

His speech makes it clear that Xi wants to continue to balance contradictory political goals such as economic growth with greater social equality on the one hand and zero-Covid on the other. On the one hand, he needs to create jobs; on the other, he needs to meet climate targets.

How and if the balance might shift in his third term, however, is something Xi left open in his speech. He leaves that to the government, whose new prime minister will probably not be decided until the end of this 20th Party Congress.

The action of a democracy activist at the Sitong Bridge in Beijing continues to echo. On the one hand, he is only one of 1.4 billion Chinese – and there is no sign of a mass movement. Theoretically, he could be pretty alone with his opinion, with only the support of a small circle of politically interested intellectuals.

On the other hand, this act has enormous symbolic value. The man has proven: Even fully monitored Beijing cannot always be controlled. That alone shows the limits of the Party’s domination over physical reality. In this first noticeable protest in years, it also became clear that Chinese civil society is not completely dormant. The smoke over the Sitong Bridge could also be seen as a sign of a brewing fire beneath the seemingly sealed surface of society. On top of that, the international media got their scoop ahead of a dull party congress.

On Thursday, the protester unfurled several banners at the road bridge in the Haidian district. He called Xi Jingping a dictator and demanded, among other things, freedom instead of lockdowns, dignity instead of lies and elections instead of a supreme leader. But equally remarkable was how he organized the protest. He had dressed up as a construction worker, pulled up in an official-looking van, and reportedly even requested the help of police officers present to secure his “construction site”. After he had calmly put up the banners, he set the fire to draw additional attention to them. This kind of ingenuity is particularly successful in China, and word travels fast whenever the authorities have been tricked.

Numerous universities and tech companies are dotted around the bridge. The area is teeming with members of the younger generation, who film everything of interest with their smartphones. As a result, the censors had their hands full. Blocked keywords at times included “fire,” “Sitong Bridge,” “brave,” “banner,” and even “Third Ring,” one of Beijing’s main streets.

The man was given the nickname “Bridge Man” on the Internet, based on the “Tank Man” who stood up to the tanks in 1989. The Twitter community in particular was quickly certain that it had identified him. His identity is said to be that of the physicist Peng Lifa. A strong indication of this: On the German science portal ResearchGate, the same protest slogans were published under his account at the same time as the action, neatly edited for sharing. Peng also owns a stake in a Beijing materials company.

Moreover, the same Peng Lifa has disappeared since Thursday, indicating his authorship. Bridge Man was arrested without resistance after the police officers discovered the message on his banners. He could now face torture, prison, and might even disappear.

All Beijing bridges are now under double surveillance, but any copycats would probably choose other places and forms to continue the protest. In the coming weeks, we will see whether his act created any sparks in the minds of other young people and spread the fire. Because smartphone cameras are everywhere, and the chaotic nature of the Internet, more protests would quickly receive attention. Perhaps the Internet is more than just the ingenious instrument of control that the CP has lately used it as. Maybe it is also a potential threat to absolute power.

The Chinese customs office was supposed to publish the trade figures for the month of September on Friday. But apparently, shortly before the CP Congress, negative reports were not welcome: In any case, for the time being, the statistics have not been published and no reasons have been given.

After all, the true extent of the crisis the Chinese economy currently faces is obvious, even without the latest batch of official data. For the first time in 30 years, economists estimate that growth in the People’s Republic has fallen below the Asian average; for the current calendar year, the World Bank predicts an expansion in gross domestic product of only 2.8 percent. It is possible that China will have to get used to such a figure in the medium term.

What sounds respectable for many OECD countries is a near disaster for the Middle Kingdom: Every year, the country must integrate more than ten million university graduates into the labor market, and in addition, the monthly disposable income of around 600 million Chinese is still only the equivalent of €150. The promise of wealth keeps them in line.

The biggest liability for the slow economic growth is unmistakably the dogmatic zero-Covid policy, which continues to dominate the lives of the 1.4 billion Chinese in the third year of the pandemic. Just how much the measures are also affecting businesses is reflected in comments made by business representatives. “Citizens are getting nervous again,” says Francis Liekens, who heads the Shanghai office of the European Chamber of Commerce (EUCC): “It’s a bit like playing roulette: Every time you ask yourself whether you should really leave your apartment or enter a certain building.” Because an unexpected lockdown could be waiting at any time. People have recently been locked up in several office towers and shopping malls in the financial metropolis after a Covid case was detected there.

Harald Kumpfert from the EUCC office in northeastern Shenyang says, “We don’t see much effort for vaccination campaigns.” Instead, he says, everything has long been about mandatory PCR testing. “It has obviously become a huge business. Some of our Chamber of Commerce partners get tested up to four times a day – every time they leave the city limits or the highway.” His colleague Christoph Schrempp from the Tianjin office reports, “The other day we had a Covid outbreak at a company with 20 cases. By 6:30 AM, the entire neighborhood was cordoned off.”

And another business representative from Chengdu tells us with a smug undertone that he had to spend four days in quarantine before his latest external appointment in a neighboring city. And that was just to spend an hour negotiating with his business partners. Chinese entrepreneurs also have to put up with such hassles. It is clear that the economy is not running smoothly.

For outsiders who do not live in China, such statements may seem increasingly surreal. Even a high-ranking medical doctor, who is currently on home leave in Europe and asked to remain anonymous, speaks of a “collective psychosis.” But Xi Jinping defended zero-Covid in his party congress speech as a national struggle that will, of course, continue.

For companies, this may sound downright mocking, but there will be no open criticism from Chinese board members for fear of repression. The consequences of the measures have long been visible to the naked eye: In Beijing, even the once most popular shopping malls are eerily empty on most weekdays, and in Shanghai, the number of people sleeping on the streets has also increased yet again.

Presumably, these are not typical homeless people, but rather migrant workers residing in the surrounding areas who are afraid to enter their homes for fear of a lockdown – and the resulting loss of their source of income.

But zero-Covid is not the only reason for the current economic woes. The real estate market no longer fulfills its function as an economic engine. Previously, it had always been possible to pump money into the housing and construction sectors to stimulate the economy. However, its bubbles have grown too large, and some of the companies have become bankrupt. Attempts to stimulate the sector are clashing with ones to consolidate it. So Xi cannot rely on his economic experts to bring him growth in the tried and true way. Fabian Kretschmer

US citizens will no longer be allowed to be involved in the development or production of microchips in China without obtaining a special license first. This is according to new export control regulations issued by US authorities last week. Previously, US citizens were already prohibited from supporting the development, manufacture or maintenance of weapons in certain countries, particularly nuclear and biological and chemical weapons. The new articles on chip manufacturing target China specifically.

The ban follows the Chips Act passed in July, with which the US government wants to massively promote semiconductor development and production in the United States. In early October, the US government also imposed export bans on American chips and manufacturing equipment to China. The background to this is that US semiconductors are not to be sold to Chinese state-affiliated companies. Microchips are particularly relevant for military and surveillance technologies.

The new regulation could have a massive impact on China’s tech world. According to the financial magazine Nikkei Asia, hundreds of entrepreneurs and developers in the field are US citizens of Chinese descent. Many have studied in the US, gained work experience there at major tech companies, and hold US citizenship. Among them is founder and CEO Gerald Yin of Advanced Micro-Fabrication Equipment Inc. China (AMEC), China’s leading chipmaker, who spent 20 years working in Silicon Valley. Also a US citizen is David H. Wang, CEO of ACM Research.

Building an independent chip ecosystem is of strategic importance to China. Experts believe the US bans could set China’s chip industry back years. jul

Germany’s President Frank-Walter Steinmeier has come under fire for a congratulatory letter to China’s President Xi Jinping. Steinmeier personally wished Xi “happiness and good health” on the occasion of the anniversary of German-Chinese relations last week. In the letter, the German president stressed the importance of “inalienable human rights” and that he wants to “work for the dignity and rights of every human being.” However, the fact that human rights violations in China had not been directly addressed now earned Steinmeier criticism from several political groups. In an interview with the German tabloid Bild, FDP liberal foreign policy expert Frank Mueller-Rosentritt called the congratulatory letter “a slap in the face for all friends of freedom, including those in China.”

In general, certain diplomatic phrases are dictated for letters on such occasions. Steinmeier did not deviate from other congratulatory letters. Friendly messages in which critical issues are avoided are nothing unusual, even between systemic rivals.

Green Party European politician Reinhard Bütikofer appeased that Steinmeier had “thankfully not left out the topic of human rights, even if he addresses it carefully.” According to the report, the Office of the Federal President rejected any criticism: Steinmeier “not only highlighted the joint successes of the past five decades, but at the same time clearly and critically addressed the challenges of the present.” ari

Sri Lanka hopes for a concession from China regarding the repayment of its loans. The country’s president, Ranil Wickremesingh, expressed optimism over the weekend to Reuters that a restructuring of the debt could be reached. Previously, Wickremesingh held talks with China’s Minister of Finance Liu Kun.

China is Sri Lanka’s biggest bilateral lender (China.Table reported). The island nation with 22 million inhabitants currently faces its worst economic crisis in decades. It has debts of around €30 billion. Besides China, the biggest lenders include Japan and India. rtr/jul

BMW denied a media report suggesting the company plans to move production of its electric Mini from the United Kingdom to China. A spokesman for the automaker said on Friday evening that no such move was planned. The Times newspaper previously reported that BMW planned to move production of the car to the People’s Republic. BMW produces about 40,000 electric minis a year at a factory on the outskirts of Oxford. rtr

Xi Jinping is poised to become the first three-term president in Chinese history when the Communist Party of China’s 20th National Congress convenes this month. That makes this an opportune time to take stock of Xi’s economic-policy record from the past ten years and explore some obvious steps to improve economic performance in the next term.

When Xi assumed China’s top political position in 2012, the economy was thriving, but it also had many serious problems. GDP had been growing at an average annual rate of 10% for over a decade. But a slowdown was inevitable, and GDP growth rates have indeed declined almost every year since 2008. Moreover, inequality was rising, with the Gini index having increased by 13 percent between 1990 and 2000. By the start of this century, inequality in China had surpassed that of the United States for the first time in the post-1978 reform era.

Meanwhile, pollution was literally killing China. By 2013, Beijing’s air had an average of 102 micrograms of PM2.5 particles per cubic meter, whereas Los Angeles – a city historically known for its air pollution – had a PM2.5 reading of only around 15. Chinese city dwellers increasingly complained about the cardiopulmonary illnesses and early mortality associated with pollution. And China was also plagued by water pollution, owing to the chemical runoff from its factories, farms, and mines. In rural areas, entire villages and towns sometimes had to move because their water supply had been irreparably contaminated.

China was also gradually losing its workforce. Historically high fertility rates of around six children per woman started to decline in the 1970s and reached their current levels of under two children per women in 2000. China’s working-age cohort shrank from 80 percent of the total population in 1970 to only 37 percent in 2012. The share of individuals over age 65 doubled, from 4 percent in 1970 to 8 percent in 2012. These trends left the government stuck between a rock and a hard place. Though policymakers needed to keep the overall population from ballooning further, they also needed to maintain the supply of young working people to support the growing elderly population.

Social discontent was rising and, according to one popular index, public perceptions of government corruption had doubled between 1991 and 2012. Around 1,300 labor strikes were documented in 2014; by 2016, that figure had more than doubled, to 2,700.

When Xi came to power, he took great pains to confront these challenges head-on. But the results have been mixed. On a positive note, PM2.5 readings in major cities like Beijing and Shanghai have been halved over the past ten years, and China’s Gini coefficient today is back below that of the US and 13 percent below its 2010 peak.

But other indicators are less favorable. Between 2012 and the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s annual GDP growth rate has either remained flat or declined. Even though the government has abolished its stringent one-child policy, fertility rates have remained very low. The share of individuals aged 65 and older today is nearly 13 percent, a new peak for the modern era. And ten years after Xi launched a highly touted anti-corruption campaign, public perceptions of corruption are higher than ever.

Still, it would be misleading to lay all of the past decade’s accomplishments and failures at Xi’s feet. Xi inherited the biggest problems he has faced, which were the unavoidable consequences of China’s previous rapid growth and political and economic history. At the same time, Xi also inherited the main policy solutions to these problems.

After all, China started requiring state-owned energy grids to invest in renewable industries all the way back in 1994, and earlier governments also emphasized policies to improve conditions for the poor. Basic medical insurance was introduced to urban areas in 1998 and to rural areas in 2003. Aggregate inequality began to decline two years prior to Xi taking office, and earlier governments regularly pursued their own anti-corruption drives.

As Xi continued many of his predecessors’ policy initiatives, the things that were improving continued to improve, and the problems that were hard to fix remained unfixed. What changed most under Xi was not the ostensible policy aims but the mode of implementation. With a few exceptions, such as the one-child policy, post-1978 Chinese policymakers before Xi tended to be cautious and discreet. Important changes, like the introduction of rural elections, were usually piloted quietly and only announced as a “national policy” when the central government felt confident that it understood how the policy would work.

This trial-and-error method had the advantage of creating political space for deliberation among important stakeholders, leading to the success of highly complex initiatives such as China’s national health policy. It also allowed for flexibility, with policies being revised to account for changing conditions or unforeseen side effects. And because these policies were not associated with any one person, the political costs of admitting mistakes were low.

Xi has dispensed with such subtleties, announcing policies personally, suddenly, and without much, if any, apparent deliberation. This modus operandi has clearly been economically harmful, even when the motivations behind the policies are benign or well-meaning.

Consider the 2021 ban on private tutoring, which was intended to curb the punishing hours that Chinese children spend studying and to reduce wealthier students’ advantages over their peers. But the rollout was so blunt and sudden that it reduced major Chinese education companies’ market capitalizations by tens of billions of dollars and simply created a black market for the same services. The economic ramifications reach beyond education. The possibility of sudden and unanticipated policy changes discourages future investments in all sectors.

Another example is Xi’s zero-COVID policy. Though it was very successful in keeping the coronavirus at bay when there were no vaccines, it has fared poorly with changing conditions. While all other countries are shifting back to business as usual – or have already done so – China seems stuck in an endless game of Whac-a-Mole.

The implications for the Chinese economy are clear: the authorities should stay the course in terms of economic-policy goals, but change their policymaking methods. Moving slowly and cautiously served China well for more than 40 years. It could work well for many more.

Nancy Qian, Professor of Managerial Economics and Decision Sciences at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, is a co-director of Northwestern University’s Global Poverty Research Lab and the Founding Director of China Econ Lab.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2022.

www.project-syndicate.org

Robin Mallick is the new director of the Goethe-Institut in Beijing. Mallick previously served as head of the Goethe-Institut in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. His predecessor Clemens Treter (China.Table already introduced him in a Profile) is now Goethe-Institut director in Seoul and, as the new director, looks after the entire East Asia region.

Jason Shen is the new Country Manager China at the German medical technology company Medi-Globe Group. The company from Bavaria’s Chiemgau region opened a branch office in Beijing to coordinate its expansion locally.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Lovers in China are willing to “trade an entire universe for a small adzuki bean” (一整个宇宙换一颗红豆 yī zhěnggè yǔzhòu huàn yī kē hóngdòu). At least, that’s how singer Fish Leong (梁静茹Liáng Jìngrú) originally sang it in her 2009 song “Love Song” (情歌 qínggē). The boy band beaus of “Mayday” (五月天 Wǔyuètiān) from Taiwan already wondered in their 2005 hit “John Lennon” how “a red bean wants to single-handedly shoulder the weight of the universe” (一颗红豆为何想单挑这宇宙 yī kē hóngdòu wèihé xiǎng dāntiāo zhè yǔzhòu). And China’s music queen Faye Wong (王菲 Wáng Fēi) straight up named an entire song after the blood-red mini bean.

We are talking about the adzuki bean, in Chinese 赤豆 chìdòu or 红豆 hóngdòu, literally “red bean”. It is found in many song lyrics, novels, and poetry lines in the Middle Kingdom, where its deep red color and long shelf life make it a symbol of longing between lovers (相思 xiāngsī), which is why it is sometimes called the “bean of desire” (相思豆xiāngsīdòu).

But we also encounter these red beans in China in candy stores and bakeries, at steamed bun stalls, and on frozen food shelves. Thanks to their sweet, nutty flavor, they are a popular ingredient in many traditional desserts, but also in many creative new ones, especially as a sweetened paste.

This “red bean paste” (红豆沙 hóngdòushā, literally “red bean sand”), a purple mush made from boiled and then mashed adzuki beans, usually sweetened with sugar or honey, gives many Chinese desserts their characteristic flavor. Originally, the dark paste originated in China’s vegetarian Buddhist cuisine, from which it started its triumphal march to other parts of Asia.

In China, “dousha” is added, among other things, as a filling to the glutinous rice balls Tangyuan (汤圆 tāngyuán), which are traditionally served at the end of the Spring Festival, as well as to the glutinous rice dumplings Zongzi (粽子 zòngzi) wrapped in banana leaves, which are eaten at the Dragon Boat Festival. It is also hard to imagine the mid-autumn festival without the classic moon cakes (月饼 yuèbǐng). Adzuki flavor is also popular in sweet baozi steamed buns (豆沙包 dòushābāo), breakfast cakes fried in fat (豆沙烧饼 dòushā shāobǐng), and sweet spring rolls.

But that is not all: China’s supermarkets now also feature adzuki bean ice cream (红豆冰淇淋 hóngdòu bīngqílín), bean paste croissants (红豆馅牛角面包 hóngdòuxiàn niújiǎo-miànbāo), red bean drink packets (红豆饮料 hóngdòu yǐnliào), adzuki bean milk tea (红豆奶茶 hóngdòu nǎichá) and many other delicious food creations.

While not everyone may be willing to trade an entire universe for an adzuki bean, nothing speaks against getting these – from a Western perspective unconventional – treats for a few yuan the next time you visit China. After all, once you’ve acquired a taste for them, a small universe of new snacks will open up to you.

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.