The discussion about the stake in a German port terminal held by the Chinese state-owned company Cosco intensifies almost by the hour. With the Ukraine war and its consequences, the affair becomes a new symbol of Germany’s disastrous dependence on authoritarian countries. Olaf Scholz, of all people, the “Zeitenwende” chancellor, still wants to seal the deal despite massive criticism – if necessary also as a compromise with a smaller share and without veto rights for Cosco.

Today, the Chinese acquisition bid is expected to be discussed by the German government. The Chancellor’s Office can no longer withstand the headwinds from the public and from within the government coalition without suffering a bitter blow to its reputation, writes Finn Mayer-Kukuck in his analysis of the Cosco debacle. “Just as there is no such thing as a little bit pregnant in nature, there is no such thing as a little bit Chinese in the port deal in Hamburg,” explained Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann of the liberal FDP, for example. It will be a difficult birth, that much is clear. The case will cast a long shadow on further cooperation with Chinese partners.

By the way: Tomorrow our colleagues at Climate.Table will publish their very first issue. The seven-member editorial team with its international network of correspondents is headed by Bernhard Pötter, one of Germany’s most renowned climate experts and a long-time observer of the international climate scene. He previously worked for major German newspapers such as Taz, Spiegel, Zeit and the French le Monde Diplomatique. Climate.Table analyzes the climate policies of the European Union and other countries around the globe, the full breadth of the international climate debate, the importance of technological breakthroughs for decarbonization, and the UN climate negotiations. It also covers key scientific studies, industry dates, and a thoroughly curated international press review. The editorial team will also report daily from the COP27 climate conference.

The planned acquisition of a stake in one of four terminals at the Port of Hamburg by the shipping company Cosco has become a symbol of Chinese investment in Germany. It is the first acquisition of high-profile infrastructure since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: The “Zeitenwende” is gripping the port business. Demands are that Germany should no longer act naively toward authoritarian and potentially aggressive states.

However, it is the Zeitenwende Chancellor Olaf Scholz himself who now undermines this call. He is in favor of a compromise in which Cosco takes a smaller stake that allows little actual influence on the business. The terminal’s IT would also remain independent of the Chinese shareholder. China.Table was the first to report on this compromise on Monday morning.

The German government is expected to discuss the Chinese takeover bid on Wednesday. However, the two smaller partners in the government coalition are united in their objection – and the new compromise has done little to change that. Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann of the liberal FDP party and chairwoman of the Defense Committee rejects the deal entirely. “Just as there is no such thing as a little bit pregnant in nature, there is no such thing as a little bit Chinese in the port deal in Hamburg,” she told the German news agency dpa.

Strack-Zimmermann accused Olaf Scholz of lacking a spine: “The flexible back belongs in the Hamburg Ballet, not in the Port of Hamburg.” China needs to see a “stop sign” in front of the European port strategy, FDP foreign policy expert Johannes Vogel told German business weekly Wirtschaftswoche. Economy Minister Robert Habeck of the Green Party and his party colleague Omid Nouripour also reiterated their warnings against dependencies.

Germany’s southern states also had something to say: The Bavarian state government has no sympathy for the sale of German infrastructure to China, said conservative politician Florian Herrmann (CSU), head of the state chancellery. From a “transport, economic and security policy perspective,” the government of the Free State opposed selling infrastructure to investors from outside the EU. This applies not only to the state’s six inland ports, but also to its airports and digital infrastructure.

Last year, Cosco’s port subsidiary signed a deal to purchase a 35 percent stake in the Tollerort terminal from port logistics company HHLA. So far, nearly all ships docked there belonged to Cosco. The port could well use both the investment and an increase in business with China. For a shipping company, in turn, it makes sense to acquire port stakes. In case of container jams, their own ships could then enter the port with priority. In return, Tollerort would become a “preferred hub” for the large shipping company from the People’s Republic. The compromise envisages a share of only 24.9 percent, which opens up fewer opportunities for influence.

From a purely economic standpoint, the deal would indeed make sense – hardly anyone doubts that. As long as Germany and China are major trading partners, many freighters will operate between the two countries. Mutual stakes in the ports strengthen relations here. But the entry of the Chinese state-owned shipping company, which is increasingly perceived as an unfriendly rival in Europe, also has a political component. Even before the invasion in February, the entry was considered controversial; the political opposition in Hamburg opposed it from the start.

Probably for this reason, another important port wants to clarify its relationship with Cosco without jeopardizing its relations with its major client. The Port of Duisburg confirmed to Table.Media on Tuesday that Cosco has no longer been involved in one of the company’s prestige projects, the Duisburg Gateway Terminal (DGT), since June.

Cosco originally planned to co-finance just under one-third of the new berth. A spokesman said the company “agreed not to disclose” the reasons for the Chinese withdrawal. Construction of the DGT began in March. Duisburg is an important terminus of the rail Silk Road; containers are transferred from ship to rail and vice versa.

Duisburger Hafen AG is now taking pains to portray relations with Cosco as completely unscathed. At the same time, it hurries to play down the significance of its ties. “Of course, no company or other institution from China has a stake in the Port of Duisburg; these are owned exclusively by the State of North Rhine-Westphalia and the City of Duisburg,” said a spokesman. He added that there was also no longer any “participation under company law” in the operating company of the gateway terminal. Duisport maintains many business partnerships and is not dependent on individual clients, he said.

Perhaps one of the reasons why the port entrance is such an excellent topic for discussion is that it is relatively straightforward and tangible. Everyone can picture a container terminal – which makes it a perfect topic for politicians to fuss over. But Germany is also far from clear about the relationship between closeness and distance to China in numerous other sectors. The debate surrounding the port terminal will be repeated a dozen times in numerous variations in the near future. The next front is the expansion of mobile communications networks. Here, too, the liberal FDP and Green politicians are scoffing at the idea of too much Chinese influence.

The previous German government wanted to keep the Chinese network supplier Huawei out of the German cell phone networks after massive public pressure. By law, it excluded “untrustworthy” providers from supplying critical parts. (At the time, incidentally, it was the social-democratic SPD that pressed for a ban of Huawei, while the conservative CDU, which was in charge at the time, had sought close ties with the Chinese provider in the interest of a fast and inexpensive network expansion). Interior Minister Nancy Faeser (SPD) is now responsible for evaluating “trustworthiness” under the IT Security Act.

Faeser is now pressing ahead with implementation and has summoned a staff of representatives from the ministries involved, the German business newspaper Handelsblatt reports. However, it is still unclear which elements of the German networks are to be considered “critical” at all and which providers are to be classified as trustworthy and which are not. A heated discussion, on the other hand, is certain.

The time of annual reports for the 2021 financial year turned into one big party. Especially for German automakers. Measured by reported profits, it was the best year in the history of the DAX. Volkswagen presented profits of €19.3 billion (7.7 percent Ebit margin), Mercedes €16 billion (12 percent Ebit margin), and BMW generated €13.4 billion in profits (12 percent Ebit margin). In China, such profits are (yet) rather unusual. Geely, for example, generated the equivalent of €692 million in profits, but had to turn over €14.6 billion to do so. That is not even a 5 percent Ebit margin.

But electromobility, of all things, could change that. One reason is that manufacturers have certainly benefited from the semiconductor shortage. The chips they had were first installed in high-priced, high-margin luxury cars. Here they have mature products in their portfolio. The other reason is that the sales share of electric vehicles is growing steadily. And part of the truth is that the most profitable automaker in 2021 was Tesla. The American EV producer presented €5.5 billion in profits, which corresponds to an Ebit margin of 12.1 percent.

German automakers still struggle in this growth market. Tesla and Chinese manufacturers, on the other hand, made impressive progress in the segment. “The development in recent years has been very positive because the economies of scale for the battery have begun to take effect, and the design of the architecture and production have become more efficient,” Dennis Schwedhelm, Senior Expert at the McKinsey Center for Future Mobility, sums up the situation. Even if there are challenges at present: “Now there are bottlenecks in the supply chain, including raw materials, which are driving up the price of semiconductors and batteries again. That doesn’t make it easy in the short term.”

One example is the electric pioneer BYD from Shenzhen. The brand managed to increase its sales by 38 percent in 2021 – to around €30 billion. At the same time, however, profits dropped by 28.1 percent – to €437 million. This is due to the crisis, of course, but also part of the strategy, as Alexander Will, Senior Expert at McKinsey in Shanghai, explains. “Chinese consumers attach a lot of value to ‘smartification’ of electric vehicles across all price ranges. Local OEMs focused in recent years on offering a competitive product to gain attention in the ‘smart’ EV segment,” Will says. “As a result, manufacturers integrated the latest technologies, such as large displays, advanced features for driver assistance systems, and the latest voice control technology, even in lower-priced vehicles. Profits were secondary at first.”

In the low-cost segments, where Chinese manufacturers lack Western competition, this has already paid off, Will emphasizes. “We’ve looked at latest-generation electric vehicles in China starting at €10,000 to €12,000 and seen that they’re profitable. Three years ago, it was different. Back then, manufacturers wanted to get to market quickly.”

This could become a problem for Western companies in particular. Because as EVs continue to become more common, the pressure to offer not only electrified premium vehicles, but also smaller EVs for the mass market, is growing. “It’s usually the case that smaller vehicles have lower margins than larger ones,” Schwedhelm says. “Now manufacturers need a wide range of models, and it’s a challenge to be profitable in the smaller vehicle segment.”

The strategy of focusing on market share rather than margins means that Chinese manufacturers have better starting conditions for this. “The EV market is at a point where other selling points are important for the customer. Above all, software and connectivity solutions. These can be played out cost-effectively across all vehicles and model series,” Will believes. But in this area, Western manufacturers are still behind the carmakers in the People’s Republic. “Unlike traditional arguments such as quality and safety, Chinese manufacturers no longer have to play catch-up with their international competitors in their domestic market when it comes to these new purchasing criteria. Here, they can increase prices and profitability.”

The monetization of vehicle data could prove to be an additional cash cow. “On the one hand, this involves additional revenue, for example from entertainment or insurance, and on the other hand, savings on costs, for example through anticipatory maintenance of vehicles. We estimate that by the end of the decade there will be a three-digit billion euro figure in value in this area, which can not only be realized by car manufacturers,” Schwedhelm calculates.

The development could become a problem for dealers. This is because EVs require far less maintenance than conventional combustion engines. That costs business. “In China, dealer networks are saying quite clearly that maintenance needs are declining, and expect customers with battery electric vehicles to spend 30 to 40 percent less on spare parts and maintenance. That’s a big problem for dealers,” Will explains. Also because car dealers in China so far followed a similar growth strategy as car brands. “Currently, they often sell vehicles at a loss, especially in the higher-priced segment. They then only recoup the money with maintenance,” says the expert. “That needs to change.”

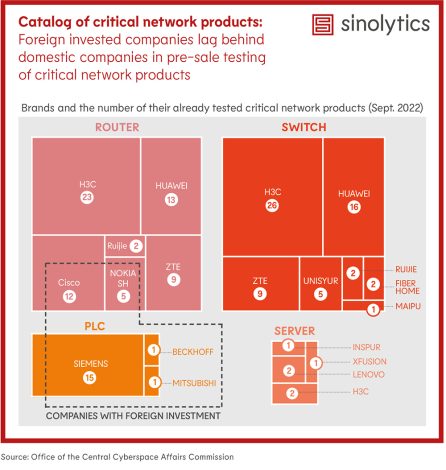

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

According to the AFP news agency, the US Department of Justice accuses two secret agents from the People’s Republic of spying on investigations into the Chinese tech company Huawei. The two Chinese citizens, He Guochun and Wang Zheng, are now initially under investigation for obstruction of justice and money laundering. According to the indictment, they allegedly tried to bribe a US justice official in order to obtain documents relating to investigations against a “global telecommunications company” from China, writes AFP.

What the spies apparently were unaware of was that the man was a double agent for the FBI. He handed over fake secret documents of the Huawei case to the spies, for which he received $41,000 in Bitcoin. The spies then offered cash and jewelry for further information. The name Huawei does not appear in the indictment. However, the data mentioned in the documents exactly matches the Huawei case.

A lawsuit against the world’s largest supplier of 5G network equipment has been ongoing in the US since January 2019. The US Department of Justice accuses Huawei and two subsidiaries of violating US sanctions on Iran. They are also accused of industrial espionage. Meng Wanzhou, the daughter of Huawei’s founder, who also serves as the company’s CFO, had been under house arrest for a time in Canada at the request of the US.

US Attorney General Merrick Garland addressed two other espionage cases on Monday. He accused China of deliberately attempting to undermine the US legal system. His department would “not tolerate that.” flee

The Chinese leadership sharply criticizes the visit of a parliamentary delegation to Taiwan. The German deputies should, “immediately cease its interaction with the separatist pro-independence forces in Taiwan,” the Foreign Ministry in Beijing said on Tuesday. Taiwan is an “inalienable part of Chinese territory,” it said. Members of the German parliament should adhere to the “one-China principle,” it added.

Members of the German Bundestag’s Human Rights Committee were received by President Tsai Ing-wen in Taipei on Monday (China.Table reported). It is the second visit of a delegation of the German Bundestag to Taiwan in a month. In addition to the current security situation, the six members of the Human Rights Committee want to get a picture of the human rights situation.

Meanwhile, Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen compared the island’s situation to Ukraine. Russia’s invasion of its neighboring country, she said, was a prime example of the kind of aggression that Beijing is capable of. “It shows an authoritarian regime will do whatever it takes to achieve expansionism,” Tsai told a meeting of international democracy activists in Taipei. “The people of Taiwan are all too familiar with such aggression. In recent years, Taiwan has been confronted by increasingly aggressive threats from China.” These included military intimidation, cyberattacks and economic blackmail. fpe

In the context of the international communist movement, there has been one 20th Party Congress of particular historical significance. In February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev removed the long-time party chairman Joseph Stalin in a secret speech and revealed the extent of his reign of terror. This criticism caused a contemporary quake throughout the socialist camp and was a decisive factor in the subsequent rift between the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China.

The 20th Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), which just ended, will not achieve a similar status in world politics, but it is already historic in a different way. It officially buries most of the institutional achievements the party had drawn as lessons from the Cultural Revolution. This is especially true for term limits for top offices and the ideal of “collective leadership”. In addition, the new election of the four members of the Politburo Standing Committee was based solely on loyalty criteria. The at-times propagated notion of “political meritocracy” and selection of the best within the Party is thus rendered absurd. Whether planned or not, nothing symbolizes the state of the Party more clearly than the humiliating treatment of the former Party Chairman Hu Jintao, who was apparently escorted off the podium against his will in front of the assembled world press. Much like in the late 1960s, blind allegiance is now a more important criterion than competence for advancing in the Party. The “collective leadership” was replaced by “centralized and unified leadership”.

Party congresses are generally convened only once key personnel decisions have been made. After all, the propaganda apparatus needs time to package the core messages appealingly and prepare them for study by local Party committees and the international public. So far, nothing was leaked to the outside world about trench warfare or controversies at the Party Congress. The election of the Central Committee, from whose members the Politburo and its Standing Committee are elected, was officially expected to have a candidate surplus of eight percent. Who failed to win the election and why remains uncertain. Two moderate representatives, Li Keqiang, who is still in office as premier, and Wang Yang are withdrawing entirely from the Party leadership. Hu Chunhua, formerly Party chief in Guangdong, who had been rumored as the future premier in the run-up to the party congress, is no longer even part of the Politburo. A successor to Xi is nowhere in sight.

Xi Jinping’s political report, which was read out in short form, turned out to be comparatively moderate, quite different from what he delivered five years earlier at the 19th Party Congress. At that time, Xi retroactively stylized his assumption of office as a turning point in history. The leadership ideology named after him was added to the Party statutes and thus formulated a new main contradiction. For political China observers, the report at the time was a feast; After all, Party congresses serve as high masses for Party ideology. Shifts in terminology and new slogans are decoded by what may seem like arcane knowledge to draw conclusions about political priorities.

In contrast, there was initially almost disappointment after Xi’s speech on October 16. Among the most important realizations was that some terms were no longer used. These included, above all, the term “political reform” and the description of the present as a “phase of strategic opportunities.” Instead, the report emphasized the critical global situation and highlighted the country’s own determination to defend national sovereignty (including the historically “necessary” annexation of Taiwan) and the revaluation of national security. To make it clear that focusing on domestic Chinese economic cycles did not mean a relapse into Mao-era autarky efforts, internal Party study documents printed the message in bold that the private sector must continue to be “unswervingly encouraged, supported and guided.”

The core messages of the speech, prepared by the Party press in colorful mind maps, highlight in particular the Party’s leadership role as the decisive advantage of the Chinese system. In this context, it is particularly interesting to compare the speech with the long version of the report, which contains about twice as many characters. Here, inner-Party loss of faith, hedonism, corruption and a weak central government are cited in detail as central problems at the time Xi took office. Xi derives his charismatic legitimacy as Party leader from overcoming this state of institutional weakness. Also only included in the long version is the sentence that “the mechanism of the accountability system of the Chairman of the Military Commission [Xi Jinping] must be completed.” What this completion is supposed to look like specifically is not mentioned.

It was widely expected that Xi Jinping’s political role and leadership ideology would be enshrined in the Party statutes even more prominently than before. In fact, both now officially function as the “core” of party rule, which is referred to as “dual establishment” (liang ge queli). The term serves as a fig leaf for the nascent transformation into a leader’s party. In recent years, the Party leadership had already broken with the key lessons from the Cultural Revolution, particularly the ban of cults of personality and the exaltation of an individual over the organization. Now the party statutes include the sentence that Xi Jinping’s ideas are the “Marxism of the 21st century.” His ideas, formally still an expression of collective wisdom, are now considered a “worldview” and epistemological “method”. This gives Xi Jinping a carte blanche: Everything he says is thus an expression of truth, even without any reference to classical Marxism.

There have been and still are voices that see the accumulation of power in the person of Xi Jinping as a consensus decision by the Party leadership to resolve structural problems in the exercise of power. This may have been the case when Xi took office in 2012. Over the years, however, the dangers have multiplied. The lines between the eradication of structural obstacles and the elimination of personal rivals are blurred.

A look at both Chinese history and the present shows that there are few things riskier than aging dictators who surround themselves with a circle of yes-men and isolate themselves from reality. The ever-growing opacity of the political system in the People’s Republic of China does its part to dry up communication channels and give symbolic details undue attention. The late phase of Maoism provides ample evidence of this: A misspelled quote, a political slip of the tongue, or damage to a leader’s portrait could lead to long prison sentences. We are not there yet, but many of the barriers that were supposed to prevent these early beginnings have been torn down.

This lack of transparency goes hand in hand with an ideological exaggeration of the Party’s “historic mission” implemented by the political leader: The national resurgence of the Chinese nation and the reunification of the fatherland. To accomplish this mission, the ranks in the Party and the military are now being closed. This does not bode well for the future. State apologists such as Jiang Shigong, professor of law at Peking University, are already calling this mission a “heavenly mandate” (tianming), outlining a quasi-transcendental role for Xi Jinping as executor of the heavenly will. The fusion of neo-Confucian ideas in particular with the leadership ideology that the 20th Party Congress now calls “Sinicized Marxism that goes with the times” (Zhongguohua shidaihua Makesi zhuyi) continues to make progress.

In the 1980s, when critical representatives of Xi Jinping’s age cohort took stock of the past and contemplated ways forward, one theory, in particular, caused a great stir. It was the critique of “ultra-stable ideological structures” by Jin Guantao, a graduate chemist who would later rise to fame as a historian. Jin argued that rulers in Chinese history had often used all-integrating ideological grand systems to give their rule permanence. Ultimately, however, social integration through ideology often prevented political and economic innovation.

Whether the ideological grand system decisively designed for Xi Jinping by Wang Huning, the current number four in the Party, is an exception is doubtful. The future outlook has undoubtedly darkened, or as the long version puts it, “It is a period in which strategic opportunities, risks, and challenges are concurrent.” It is to be hoped that the global risks of self-isolation at the Party top will be recognized and remedied in time.

Daniel Leese is a professor of sinology at the Albert Ludwig University in Freiburg. Most recently, he published the multi-award-winning work “Maos Langer Schatten” (Mao’s Long Shadow) (2020). In spring 2023, Verlag C.H. Beck will publish an anthology on contemporary Chinese thought, edited by him and the publicist Shi Ming.

The term “compliance” only originally described adherence to applicable laws, administrative regulations and voluntary codes. Compliance originates from the Anglo-American legal sphere, where companies have been required since the 1930s to take measures to prevent legal violations in their own operations on the basis of so-called “regulated self-regulation”.

Compared to developments in Western countries, compliance arrived relatively late in China. If the importance of compliance is measured, among other things, by the number of newly enacted and revised laws, the following overview clearly shows that the significance of compliance increased sharply in China over the past eight years: from 2013 to 2021, legislative processes increased sixfold!

In addition, the Chinese government has identified “compliance” as a useful tool against nepotism and corruption in business and politics. Since then, even the famous networks (关系 “Guanxi”), consisting of connections to other companies, authorities and social representatives, can no longer solve every problem or provide advantages.

Xi Jinping’s extensive anti-corruption campaign reinforced this development. Public officials now adhere more strictly to the legislative framework – and even refuse to exercise the leeway granted by law. Authorities also rely on digital systems that monitor compliance processes and make possible influences in the decision-making process more easily visible.

The government’s anti-corruption campaign also resulted in changes to the law, according to which the catalog of penalties has been tightened and local and foreign-invested companies may and should be audited and monitored more closely. In this context, the Chinese government also advocated the implementation of compliance structures and issued corresponding legal obligations.

The social credit system, including the corporate social credit system, is one of the cornerstones of this development. Planned since 2014, it has been active since the beginning of 2021, linking government data to rate individuals, companies and other organizations. This involves integrating local, provincial and national data and records into central databases, which are then used to create a rating or assign credit points that can be accessed online and by the public.

However, a complete analysis has not (yet) taken place. However, there was an amendment at the beginning of 2022, according to which companies are to be classified in dynamic risk classes ABCD in the foreseeable future to facilitate classification and enable faster action.

In addition, as in German law, general civil, administrative and criminal compliance obligations apply, under which executives, directors and legal representatives of companies can be held liable for any violations. Furthermore, China has numerous special provisions under which members of management and other responsible parties can be held personally liable.

The specific legal liability bases are found in various laws and administrative regulations, such as the PRC Export Control Law of December 1, 2020, the PRC Workplace Safety Law of September 1, 2021, the Anti-Monopoly Law amended in August 2022, or new laws in the field of data protection and data and cybersecurity. Here, in addition to more than 290 laws and thousands of national, regional and local administrative regulations, numerous voluntary, as well as mandatory industry standards fall within compliance requirements.

However, compliance no longer requires only adherence to rules, but also the introduction of compliance management systems (CMS) and other measures to ensure regulatory compliance within companies, including software solutions or whistleblower systems.

The growing complexity of the legal framework means that companies need comprehensive documentation and constant updates of the relevant laws, administrative regulations and mandatory industry standards. The first digital compliance solutions, such as web-based compliance management software, support foreign-invested companies in China in reviewing relevant legal regulations, providing audit-proof documentation, and transparently delegating tasks to specific employees, helping companies in maintaining an overview and also ensuring compliance in exchanges with authorities.

In addition, electronic whistleblowing systems can help avoid or reduce direct reports of legal violations to authorities and give management the opportunity to take necessary corrective measures on time. Local ombudsmen can receive tips via the electronic whistleblowing system and communicate with the whistleblower in the local language, taking into account local cultural characteristics, and carry out a fact-finding process in accordance with local law before conducting a legal tip assessment.

The introduction of a CMS and the formulation of internal corporate standards, the early detection of violations or the verifiable addressing of grievances within the company usually improve the company’s rating and regularly result in more lenient sanctions.

Rainer Burkardt is the founder and managing director of the Chinese law firm Burkardt & Partner in Shanghai. He has worked on foreign law issues in China for over 25 years and most recently served as an arbitrator at the Shanghai International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission.

As managing director of Martin Mantz Compliance Solutions in the People’s Republic of China, Dominik Nowak assists international projects related to digital compliance organization and is a contact for companies.

This article is published as part of the Global China Conversations event series of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). This Thursday (17.10.2022, 11:00 a.m.), the online event is titled “Compliance in China under the Social Credit System and Growing Regulation: What are the Challenges Companies face?” China.Table is a media partner of the event series.

Mark Czelnik joined Cariad, Volkswagen’s automotive software division, as Head of ICAS, Platform and HMI China in October. Based on regional customer requirements, Czelnik will be responsible for research, pre-development, concept development and series development of Cariad software from Beijing.

Sefa Yildiz joined IT consulting firm Bulheller in Beijing in September to head the Smart Logistics rollout for SAP. Yildiz previously worked for Bulheller as an IT consultant at the company’s headquarters in Stuttgart.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

There is no such thing as a harvest festival in China. Nevertheless, farmers in the province of Shandong, China’s breadbasket, still celebrate the fall harvest in their own way: This farmer proudly whirls the seeds through the air to show how rich his harvest is this season.

The discussion about the stake in a German port terminal held by the Chinese state-owned company Cosco intensifies almost by the hour. With the Ukraine war and its consequences, the affair becomes a new symbol of Germany’s disastrous dependence on authoritarian countries. Olaf Scholz, of all people, the “Zeitenwende” chancellor, still wants to seal the deal despite massive criticism – if necessary also as a compromise with a smaller share and without veto rights for Cosco.

Today, the Chinese acquisition bid is expected to be discussed by the German government. The Chancellor’s Office can no longer withstand the headwinds from the public and from within the government coalition without suffering a bitter blow to its reputation, writes Finn Mayer-Kukuck in his analysis of the Cosco debacle. “Just as there is no such thing as a little bit pregnant in nature, there is no such thing as a little bit Chinese in the port deal in Hamburg,” explained Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann of the liberal FDP, for example. It will be a difficult birth, that much is clear. The case will cast a long shadow on further cooperation with Chinese partners.

By the way: Tomorrow our colleagues at Climate.Table will publish their very first issue. The seven-member editorial team with its international network of correspondents is headed by Bernhard Pötter, one of Germany’s most renowned climate experts and a long-time observer of the international climate scene. He previously worked for major German newspapers such as Taz, Spiegel, Zeit and the French le Monde Diplomatique. Climate.Table analyzes the climate policies of the European Union and other countries around the globe, the full breadth of the international climate debate, the importance of technological breakthroughs for decarbonization, and the UN climate negotiations. It also covers key scientific studies, industry dates, and a thoroughly curated international press review. The editorial team will also report daily from the COP27 climate conference.

The planned acquisition of a stake in one of four terminals at the Port of Hamburg by the shipping company Cosco has become a symbol of Chinese investment in Germany. It is the first acquisition of high-profile infrastructure since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: The “Zeitenwende” is gripping the port business. Demands are that Germany should no longer act naively toward authoritarian and potentially aggressive states.

However, it is the Zeitenwende Chancellor Olaf Scholz himself who now undermines this call. He is in favor of a compromise in which Cosco takes a smaller stake that allows little actual influence on the business. The terminal’s IT would also remain independent of the Chinese shareholder. China.Table was the first to report on this compromise on Monday morning.

The German government is expected to discuss the Chinese takeover bid on Wednesday. However, the two smaller partners in the government coalition are united in their objection – and the new compromise has done little to change that. Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann of the liberal FDP party and chairwoman of the Defense Committee rejects the deal entirely. “Just as there is no such thing as a little bit pregnant in nature, there is no such thing as a little bit Chinese in the port deal in Hamburg,” she told the German news agency dpa.

Strack-Zimmermann accused Olaf Scholz of lacking a spine: “The flexible back belongs in the Hamburg Ballet, not in the Port of Hamburg.” China needs to see a “stop sign” in front of the European port strategy, FDP foreign policy expert Johannes Vogel told German business weekly Wirtschaftswoche. Economy Minister Robert Habeck of the Green Party and his party colleague Omid Nouripour also reiterated their warnings against dependencies.

Germany’s southern states also had something to say: The Bavarian state government has no sympathy for the sale of German infrastructure to China, said conservative politician Florian Herrmann (CSU), head of the state chancellery. From a “transport, economic and security policy perspective,” the government of the Free State opposed selling infrastructure to investors from outside the EU. This applies not only to the state’s six inland ports, but also to its airports and digital infrastructure.

Last year, Cosco’s port subsidiary signed a deal to purchase a 35 percent stake in the Tollerort terminal from port logistics company HHLA. So far, nearly all ships docked there belonged to Cosco. The port could well use both the investment and an increase in business with China. For a shipping company, in turn, it makes sense to acquire port stakes. In case of container jams, their own ships could then enter the port with priority. In return, Tollerort would become a “preferred hub” for the large shipping company from the People’s Republic. The compromise envisages a share of only 24.9 percent, which opens up fewer opportunities for influence.

From a purely economic standpoint, the deal would indeed make sense – hardly anyone doubts that. As long as Germany and China are major trading partners, many freighters will operate between the two countries. Mutual stakes in the ports strengthen relations here. But the entry of the Chinese state-owned shipping company, which is increasingly perceived as an unfriendly rival in Europe, also has a political component. Even before the invasion in February, the entry was considered controversial; the political opposition in Hamburg opposed it from the start.

Probably for this reason, another important port wants to clarify its relationship with Cosco without jeopardizing its relations with its major client. The Port of Duisburg confirmed to Table.Media on Tuesday that Cosco has no longer been involved in one of the company’s prestige projects, the Duisburg Gateway Terminal (DGT), since June.

Cosco originally planned to co-finance just under one-third of the new berth. A spokesman said the company “agreed not to disclose” the reasons for the Chinese withdrawal. Construction of the DGT began in March. Duisburg is an important terminus of the rail Silk Road; containers are transferred from ship to rail and vice versa.

Duisburger Hafen AG is now taking pains to portray relations with Cosco as completely unscathed. At the same time, it hurries to play down the significance of its ties. “Of course, no company or other institution from China has a stake in the Port of Duisburg; these are owned exclusively by the State of North Rhine-Westphalia and the City of Duisburg,” said a spokesman. He added that there was also no longer any “participation under company law” in the operating company of the gateway terminal. Duisport maintains many business partnerships and is not dependent on individual clients, he said.

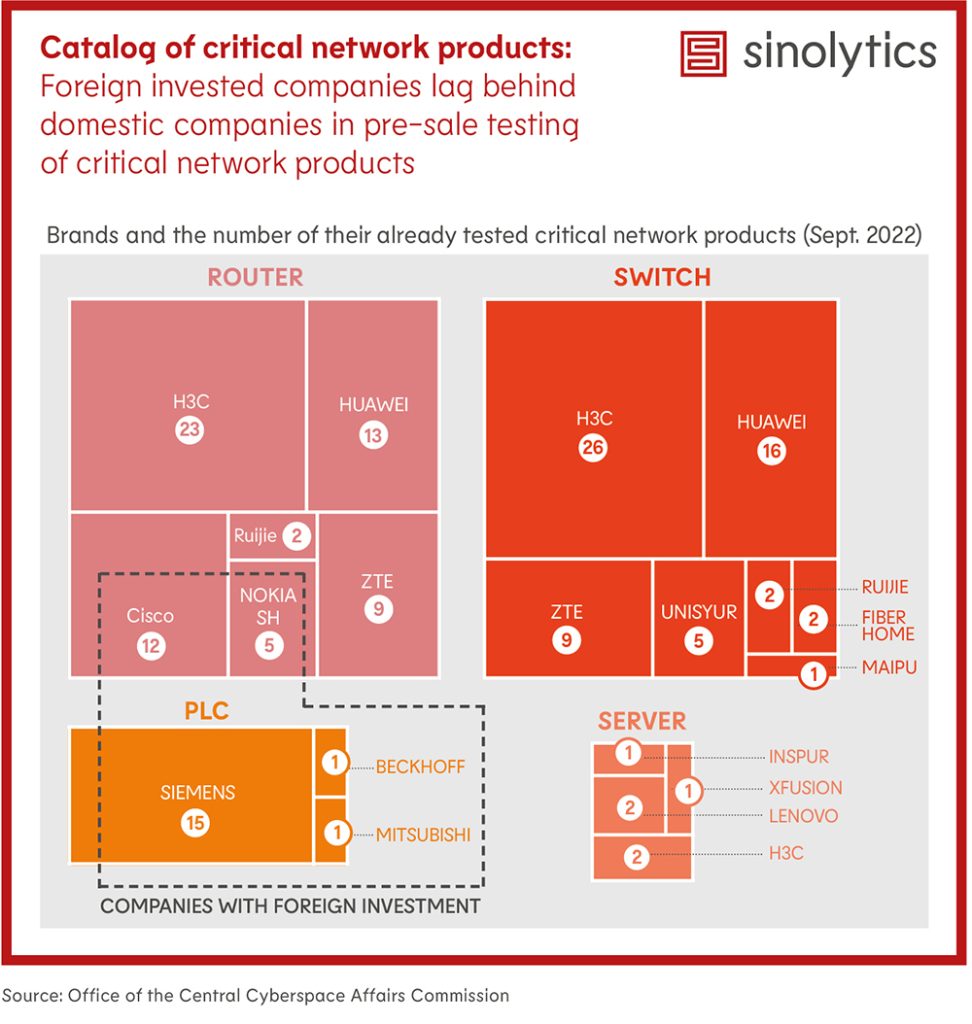

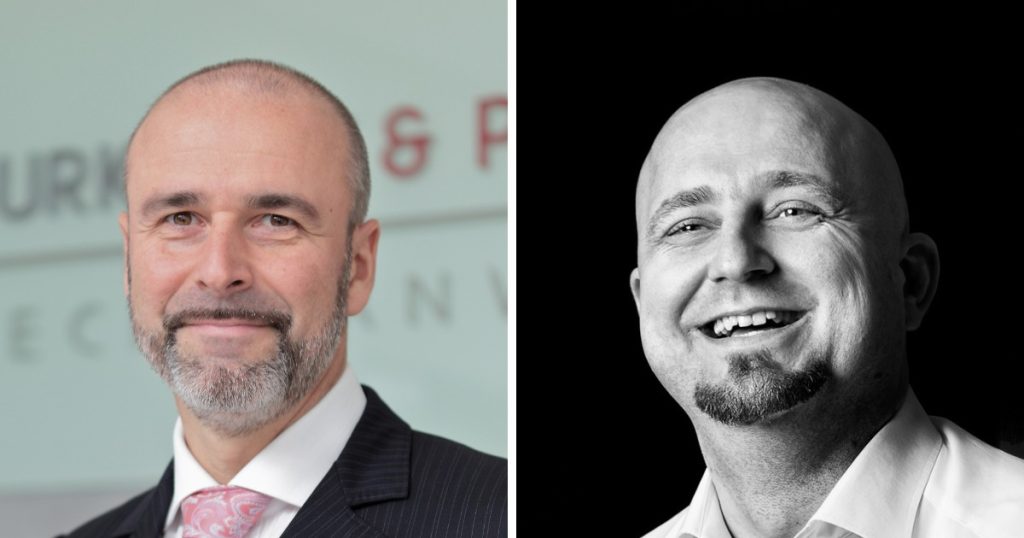

Perhaps one of the reasons why the port entrance is such an excellent topic for discussion is that it is relatively straightforward and tangible. Everyone can picture a container terminal – which makes it a perfect topic for politicians to fuss over. But Germany is also far from clear about the relationship between closeness and distance to China in numerous other sectors. The debate surrounding the port terminal will be repeated a dozen times in numerous variations in the near future. The next front is the expansion of mobile communications networks. Here, too, the liberal FDP and Green politicians are scoffing at the idea of too much Chinese influence.

The previous German government wanted to keep the Chinese network supplier Huawei out of the German cell phone networks after massive public pressure. By law, it excluded “untrustworthy” providers from supplying critical parts. (At the time, incidentally, it was the social-democratic SPD that pressed for a ban of Huawei, while the conservative CDU, which was in charge at the time, had sought close ties with the Chinese provider in the interest of a fast and inexpensive network expansion). Interior Minister Nancy Faeser (SPD) is now responsible for evaluating “trustworthiness” under the IT Security Act.

Faeser is now pressing ahead with implementation and has summoned a staff of representatives from the ministries involved, the German business newspaper Handelsblatt reports. However, it is still unclear which elements of the German networks are to be considered “critical” at all and which providers are to be classified as trustworthy and which are not. A heated discussion, on the other hand, is certain.

The time of annual reports for the 2021 financial year turned into one big party. Especially for German automakers. Measured by reported profits, it was the best year in the history of the DAX. Volkswagen presented profits of €19.3 billion (7.7 percent Ebit margin), Mercedes €16 billion (12 percent Ebit margin), and BMW generated €13.4 billion in profits (12 percent Ebit margin). In China, such profits are (yet) rather unusual. Geely, for example, generated the equivalent of €692 million in profits, but had to turn over €14.6 billion to do so. That is not even a 5 percent Ebit margin.

But electromobility, of all things, could change that. One reason is that manufacturers have certainly benefited from the semiconductor shortage. The chips they had were first installed in high-priced, high-margin luxury cars. Here they have mature products in their portfolio. The other reason is that the sales share of electric vehicles is growing steadily. And part of the truth is that the most profitable automaker in 2021 was Tesla. The American EV producer presented €5.5 billion in profits, which corresponds to an Ebit margin of 12.1 percent.

German automakers still struggle in this growth market. Tesla and Chinese manufacturers, on the other hand, made impressive progress in the segment. “The development in recent years has been very positive because the economies of scale for the battery have begun to take effect, and the design of the architecture and production have become more efficient,” Dennis Schwedhelm, Senior Expert at the McKinsey Center for Future Mobility, sums up the situation. Even if there are challenges at present: “Now there are bottlenecks in the supply chain, including raw materials, which are driving up the price of semiconductors and batteries again. That doesn’t make it easy in the short term.”

One example is the electric pioneer BYD from Shenzhen. The brand managed to increase its sales by 38 percent in 2021 – to around €30 billion. At the same time, however, profits dropped by 28.1 percent – to €437 million. This is due to the crisis, of course, but also part of the strategy, as Alexander Will, Senior Expert at McKinsey in Shanghai, explains. “Chinese consumers attach a lot of value to ‘smartification’ of electric vehicles across all price ranges. Local OEMs focused in recent years on offering a competitive product to gain attention in the ‘smart’ EV segment,” Will says. “As a result, manufacturers integrated the latest technologies, such as large displays, advanced features for driver assistance systems, and the latest voice control technology, even in lower-priced vehicles. Profits were secondary at first.”

In the low-cost segments, where Chinese manufacturers lack Western competition, this has already paid off, Will emphasizes. “We’ve looked at latest-generation electric vehicles in China starting at €10,000 to €12,000 and seen that they’re profitable. Three years ago, it was different. Back then, manufacturers wanted to get to market quickly.”

This could become a problem for Western companies in particular. Because as EVs continue to become more common, the pressure to offer not only electrified premium vehicles, but also smaller EVs for the mass market, is growing. “It’s usually the case that smaller vehicles have lower margins than larger ones,” Schwedhelm says. “Now manufacturers need a wide range of models, and it’s a challenge to be profitable in the smaller vehicle segment.”

The strategy of focusing on market share rather than margins means that Chinese manufacturers have better starting conditions for this. “The EV market is at a point where other selling points are important for the customer. Above all, software and connectivity solutions. These can be played out cost-effectively across all vehicles and model series,” Will believes. But in this area, Western manufacturers are still behind the carmakers in the People’s Republic. “Unlike traditional arguments such as quality and safety, Chinese manufacturers no longer have to play catch-up with their international competitors in their domestic market when it comes to these new purchasing criteria. Here, they can increase prices and profitability.”

The monetization of vehicle data could prove to be an additional cash cow. “On the one hand, this involves additional revenue, for example from entertainment or insurance, and on the other hand, savings on costs, for example through anticipatory maintenance of vehicles. We estimate that by the end of the decade there will be a three-digit billion euro figure in value in this area, which can not only be realized by car manufacturers,” Schwedhelm calculates.

The development could become a problem for dealers. This is because EVs require far less maintenance than conventional combustion engines. That costs business. “In China, dealer networks are saying quite clearly that maintenance needs are declining, and expect customers with battery electric vehicles to spend 30 to 40 percent less on spare parts and maintenance. That’s a big problem for dealers,” Will explains. Also because car dealers in China so far followed a similar growth strategy as car brands. “Currently, they often sell vehicles at a loss, especially in the higher-priced segment. They then only recoup the money with maintenance,” says the expert. “That needs to change.”

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

According to the AFP news agency, the US Department of Justice accuses two secret agents from the People’s Republic of spying on investigations into the Chinese tech company Huawei. The two Chinese citizens, He Guochun and Wang Zheng, are now initially under investigation for obstruction of justice and money laundering. According to the indictment, they allegedly tried to bribe a US justice official in order to obtain documents relating to investigations against a “global telecommunications company” from China, writes AFP.

What the spies apparently were unaware of was that the man was a double agent for the FBI. He handed over fake secret documents of the Huawei case to the spies, for which he received $41,000 in Bitcoin. The spies then offered cash and jewelry for further information. The name Huawei does not appear in the indictment. However, the data mentioned in the documents exactly matches the Huawei case.

A lawsuit against the world’s largest supplier of 5G network equipment has been ongoing in the US since January 2019. The US Department of Justice accuses Huawei and two subsidiaries of violating US sanctions on Iran. They are also accused of industrial espionage. Meng Wanzhou, the daughter of Huawei’s founder, who also serves as the company’s CFO, had been under house arrest for a time in Canada at the request of the US.

US Attorney General Merrick Garland addressed two other espionage cases on Monday. He accused China of deliberately attempting to undermine the US legal system. His department would “not tolerate that.” flee

The Chinese leadership sharply criticizes the visit of a parliamentary delegation to Taiwan. The German deputies should, “immediately cease its interaction with the separatist pro-independence forces in Taiwan,” the Foreign Ministry in Beijing said on Tuesday. Taiwan is an “inalienable part of Chinese territory,” it said. Members of the German parliament should adhere to the “one-China principle,” it added.

Members of the German Bundestag’s Human Rights Committee were received by President Tsai Ing-wen in Taipei on Monday (China.Table reported). It is the second visit of a delegation of the German Bundestag to Taiwan in a month. In addition to the current security situation, the six members of the Human Rights Committee want to get a picture of the human rights situation.

Meanwhile, Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen compared the island’s situation to Ukraine. Russia’s invasion of its neighboring country, she said, was a prime example of the kind of aggression that Beijing is capable of. “It shows an authoritarian regime will do whatever it takes to achieve expansionism,” Tsai told a meeting of international democracy activists in Taipei. “The people of Taiwan are all too familiar with such aggression. In recent years, Taiwan has been confronted by increasingly aggressive threats from China.” These included military intimidation, cyberattacks and economic blackmail. fpe

In the context of the international communist movement, there has been one 20th Party Congress of particular historical significance. In February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev removed the long-time party chairman Joseph Stalin in a secret speech and revealed the extent of his reign of terror. This criticism caused a contemporary quake throughout the socialist camp and was a decisive factor in the subsequent rift between the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China.

The 20th Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), which just ended, will not achieve a similar status in world politics, but it is already historic in a different way. It officially buries most of the institutional achievements the party had drawn as lessons from the Cultural Revolution. This is especially true for term limits for top offices and the ideal of “collective leadership”. In addition, the new election of the four members of the Politburo Standing Committee was based solely on loyalty criteria. The at-times propagated notion of “political meritocracy” and selection of the best within the Party is thus rendered absurd. Whether planned or not, nothing symbolizes the state of the Party more clearly than the humiliating treatment of the former Party Chairman Hu Jintao, who was apparently escorted off the podium against his will in front of the assembled world press. Much like in the late 1960s, blind allegiance is now a more important criterion than competence for advancing in the Party. The “collective leadership” was replaced by “centralized and unified leadership”.

Party congresses are generally convened only once key personnel decisions have been made. After all, the propaganda apparatus needs time to package the core messages appealingly and prepare them for study by local Party committees and the international public. So far, nothing was leaked to the outside world about trench warfare or controversies at the Party Congress. The election of the Central Committee, from whose members the Politburo and its Standing Committee are elected, was officially expected to have a candidate surplus of eight percent. Who failed to win the election and why remains uncertain. Two moderate representatives, Li Keqiang, who is still in office as premier, and Wang Yang are withdrawing entirely from the Party leadership. Hu Chunhua, formerly Party chief in Guangdong, who had been rumored as the future premier in the run-up to the party congress, is no longer even part of the Politburo. A successor to Xi is nowhere in sight.

Xi Jinping’s political report, which was read out in short form, turned out to be comparatively moderate, quite different from what he delivered five years earlier at the 19th Party Congress. At that time, Xi retroactively stylized his assumption of office as a turning point in history. The leadership ideology named after him was added to the Party statutes and thus formulated a new main contradiction. For political China observers, the report at the time was a feast; After all, Party congresses serve as high masses for Party ideology. Shifts in terminology and new slogans are decoded by what may seem like arcane knowledge to draw conclusions about political priorities.

In contrast, there was initially almost disappointment after Xi’s speech on October 16. Among the most important realizations was that some terms were no longer used. These included, above all, the term “political reform” and the description of the present as a “phase of strategic opportunities.” Instead, the report emphasized the critical global situation and highlighted the country’s own determination to defend national sovereignty (including the historically “necessary” annexation of Taiwan) and the revaluation of national security. To make it clear that focusing on domestic Chinese economic cycles did not mean a relapse into Mao-era autarky efforts, internal Party study documents printed the message in bold that the private sector must continue to be “unswervingly encouraged, supported and guided.”

The core messages of the speech, prepared by the Party press in colorful mind maps, highlight in particular the Party’s leadership role as the decisive advantage of the Chinese system. In this context, it is particularly interesting to compare the speech with the long version of the report, which contains about twice as many characters. Here, inner-Party loss of faith, hedonism, corruption and a weak central government are cited in detail as central problems at the time Xi took office. Xi derives his charismatic legitimacy as Party leader from overcoming this state of institutional weakness. Also only included in the long version is the sentence that “the mechanism of the accountability system of the Chairman of the Military Commission [Xi Jinping] must be completed.” What this completion is supposed to look like specifically is not mentioned.

It was widely expected that Xi Jinping’s political role and leadership ideology would be enshrined in the Party statutes even more prominently than before. In fact, both now officially function as the “core” of party rule, which is referred to as “dual establishment” (liang ge queli). The term serves as a fig leaf for the nascent transformation into a leader’s party. In recent years, the Party leadership had already broken with the key lessons from the Cultural Revolution, particularly the ban of cults of personality and the exaltation of an individual over the organization. Now the party statutes include the sentence that Xi Jinping’s ideas are the “Marxism of the 21st century.” His ideas, formally still an expression of collective wisdom, are now considered a “worldview” and epistemological “method”. This gives Xi Jinping a carte blanche: Everything he says is thus an expression of truth, even without any reference to classical Marxism.

There have been and still are voices that see the accumulation of power in the person of Xi Jinping as a consensus decision by the Party leadership to resolve structural problems in the exercise of power. This may have been the case when Xi took office in 2012. Over the years, however, the dangers have multiplied. The lines between the eradication of structural obstacles and the elimination of personal rivals are blurred.

A look at both Chinese history and the present shows that there are few things riskier than aging dictators who surround themselves with a circle of yes-men and isolate themselves from reality. The ever-growing opacity of the political system in the People’s Republic of China does its part to dry up communication channels and give symbolic details undue attention. The late phase of Maoism provides ample evidence of this: A misspelled quote, a political slip of the tongue, or damage to a leader’s portrait could lead to long prison sentences. We are not there yet, but many of the barriers that were supposed to prevent these early beginnings have been torn down.

This lack of transparency goes hand in hand with an ideological exaggeration of the Party’s “historic mission” implemented by the political leader: The national resurgence of the Chinese nation and the reunification of the fatherland. To accomplish this mission, the ranks in the Party and the military are now being closed. This does not bode well for the future. State apologists such as Jiang Shigong, professor of law at Peking University, are already calling this mission a “heavenly mandate” (tianming), outlining a quasi-transcendental role for Xi Jinping as executor of the heavenly will. The fusion of neo-Confucian ideas in particular with the leadership ideology that the 20th Party Congress now calls “Sinicized Marxism that goes with the times” (Zhongguohua shidaihua Makesi zhuyi) continues to make progress.

In the 1980s, when critical representatives of Xi Jinping’s age cohort took stock of the past and contemplated ways forward, one theory, in particular, caused a great stir. It was the critique of “ultra-stable ideological structures” by Jin Guantao, a graduate chemist who would later rise to fame as a historian. Jin argued that rulers in Chinese history had often used all-integrating ideological grand systems to give their rule permanence. Ultimately, however, social integration through ideology often prevented political and economic innovation.

Whether the ideological grand system decisively designed for Xi Jinping by Wang Huning, the current number four in the Party, is an exception is doubtful. The future outlook has undoubtedly darkened, or as the long version puts it, “It is a period in which strategic opportunities, risks, and challenges are concurrent.” It is to be hoped that the global risks of self-isolation at the Party top will be recognized and remedied in time.

Daniel Leese is a professor of sinology at the Albert Ludwig University in Freiburg. Most recently, he published the multi-award-winning work “Maos Langer Schatten” (Mao’s Long Shadow) (2020). In spring 2023, Verlag C.H. Beck will publish an anthology on contemporary Chinese thought, edited by him and the publicist Shi Ming.

The term “compliance” only originally described adherence to applicable laws, administrative regulations and voluntary codes. Compliance originates from the Anglo-American legal sphere, where companies have been required since the 1930s to take measures to prevent legal violations in their own operations on the basis of so-called “regulated self-regulation”.

Compared to developments in Western countries, compliance arrived relatively late in China. If the importance of compliance is measured, among other things, by the number of newly enacted and revised laws, the following overview clearly shows that the significance of compliance increased sharply in China over the past eight years: from 2013 to 2021, legislative processes increased sixfold!

In addition, the Chinese government has identified “compliance” as a useful tool against nepotism and corruption in business and politics. Since then, even the famous networks (关系 “Guanxi”), consisting of connections to other companies, authorities and social representatives, can no longer solve every problem or provide advantages.

Xi Jinping’s extensive anti-corruption campaign reinforced this development. Public officials now adhere more strictly to the legislative framework – and even refuse to exercise the leeway granted by law. Authorities also rely on digital systems that monitor compliance processes and make possible influences in the decision-making process more easily visible.

The government’s anti-corruption campaign also resulted in changes to the law, according to which the catalog of penalties has been tightened and local and foreign-invested companies may and should be audited and monitored more closely. In this context, the Chinese government also advocated the implementation of compliance structures and issued corresponding legal obligations.

The social credit system, including the corporate social credit system, is one of the cornerstones of this development. Planned since 2014, it has been active since the beginning of 2021, linking government data to rate individuals, companies and other organizations. This involves integrating local, provincial and national data and records into central databases, which are then used to create a rating or assign credit points that can be accessed online and by the public.

However, a complete analysis has not (yet) taken place. However, there was an amendment at the beginning of 2022, according to which companies are to be classified in dynamic risk classes ABCD in the foreseeable future to facilitate classification and enable faster action.

In addition, as in German law, general civil, administrative and criminal compliance obligations apply, under which executives, directors and legal representatives of companies can be held liable for any violations. Furthermore, China has numerous special provisions under which members of management and other responsible parties can be held personally liable.

The specific legal liability bases are found in various laws and administrative regulations, such as the PRC Export Control Law of December 1, 2020, the PRC Workplace Safety Law of September 1, 2021, the Anti-Monopoly Law amended in August 2022, or new laws in the field of data protection and data and cybersecurity. Here, in addition to more than 290 laws and thousands of national, regional and local administrative regulations, numerous voluntary, as well as mandatory industry standards fall within compliance requirements.

However, compliance no longer requires only adherence to rules, but also the introduction of compliance management systems (CMS) and other measures to ensure regulatory compliance within companies, including software solutions or whistleblower systems.

The growing complexity of the legal framework means that companies need comprehensive documentation and constant updates of the relevant laws, administrative regulations and mandatory industry standards. The first digital compliance solutions, such as web-based compliance management software, support foreign-invested companies in China in reviewing relevant legal regulations, providing audit-proof documentation, and transparently delegating tasks to specific employees, helping companies in maintaining an overview and also ensuring compliance in exchanges with authorities.

In addition, electronic whistleblowing systems can help avoid or reduce direct reports of legal violations to authorities and give management the opportunity to take necessary corrective measures on time. Local ombudsmen can receive tips via the electronic whistleblowing system and communicate with the whistleblower in the local language, taking into account local cultural characteristics, and carry out a fact-finding process in accordance with local law before conducting a legal tip assessment.

The introduction of a CMS and the formulation of internal corporate standards, the early detection of violations or the verifiable addressing of grievances within the company usually improve the company’s rating and regularly result in more lenient sanctions.

Rainer Burkardt is the founder and managing director of the Chinese law firm Burkardt & Partner in Shanghai. He has worked on foreign law issues in China for over 25 years and most recently served as an arbitrator at the Shanghai International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission.

As managing director of Martin Mantz Compliance Solutions in the People’s Republic of China, Dominik Nowak assists international projects related to digital compliance organization and is a contact for companies.

This article is published as part of the Global China Conversations event series of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). This Thursday (17.10.2022, 11:00 a.m.), the online event is titled “Compliance in China under the Social Credit System and Growing Regulation: What are the Challenges Companies face?” China.Table is a media partner of the event series.

Mark Czelnik joined Cariad, Volkswagen’s automotive software division, as Head of ICAS, Platform and HMI China in October. Based on regional customer requirements, Czelnik will be responsible for research, pre-development, concept development and series development of Cariad software from Beijing.

Sefa Yildiz joined IT consulting firm Bulheller in Beijing in September to head the Smart Logistics rollout for SAP. Yildiz previously worked for Bulheller as an IT consultant at the company’s headquarters in Stuttgart.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

There is no such thing as a harvest festival in China. Nevertheless, farmers in the province of Shandong, China’s breadbasket, still celebrate the fall harvest in their own way: This farmer proudly whirls the seeds through the air to show how rich his harvest is this season.